From Resistance to Allied Victory

From Resistance to Allied Victory

Resistance to fascism began early in the war. Having escaped from France to London in 1940, General Charles de Gaulle directed from a distance the Free French government and its forces—a mixed organization of troops of colonized Asians and Africans, soldiers who had escaped via Dunkirk, and volunteers from other occupied countries. Less well-known than the Free French, resisters in occupied Europe fought in Communist-dominated groups, some of which gathered information to aid the Allied invasion of the continent. Rural groups called partisans not only planned assassinations of traitors and German officers but also bombed bridges, rail lines, and military facilities. Although the Catholic church supported Mussolini in Italy and endorsed the Croatian puppet government’s slaughter of a million Serbs, Catholic and Protestant clergy and their parishioners were among those who set up resistance networks, often hiding Jews and fugitives. The Polish resistance attacked imported German settlers; individuals such as Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg saved thousands of Jews.

People also fought back through everyday activities. Homemakers circulated newsletters urging demonstrations at prisons where civilians were detained. In central Europe, hikers smuggled Jews and others over dangerous mountain passes. Danish villagers created vast escape networks, and countless thousands across Europe volunteered to be part of escape routes. Women resisters used stereotypes to good advantage, often carrying weapons to assassination sites in the correct belief that Nazis would rarely suspect or search them. “Naturally the Germans didn’t think that a woman could have carried a bomb,” explained one Italian resister. Resistance kept alive the liberal ideal of individual action in the face of tyranny.

Both subtle and dramatically visible resistance took place in the fascist countries. Couples in Germany and Italy limited family size in defiance of pro-birth policies. In July 1944, a group of German military officers, fearing their country’s military humiliation, tried but failed to assassinate Hitler—one of several such attempts. Wounded and shaken, Hitler mercilessly tortured and killed hundreds of conspirators, innocent friends, and family members. Some ask whether the assassination attempt came too late in the war to count as resistance. However, some five million Germans alone, and millions more of other nationalities, lost their lives in the last nine months of the war. Had Hitler died even as late as the summer of 1944, the relief to humanity would have been considerable.

Amid civilian resistance, Allied forces turned the frontline war against the Axis powers beginning with the battle of Stalingrad in 1942–1943 (Map 26.4). The German army sought Soviet oil through capturing this city. Months of ferocious house-to-house fighting ended when the Soviet army captured the ninety thousand German survivors in February 1943. Meanwhile, the British army in North Africa held against German troops under Erwin Rommel, a skilled practitioner of the new kind of mobile warfare. He aimed to capture the Suez Canal and thus gain access to Middle Eastern oil, but the Allies’ code-breaking capacity ultimately helped them block the capture of Egypt and take Morocco and Algeria in the fall of 1942. After driving Rommel out of Africa, the Allies landed in Sicily in July 1943, provoking a German invasion. The slow, bitter fight for the Italian peninsula lasted until April 1945, when Allied forces finally triumphed. After Italy’s liberation, partisans shot Mussolini and his mistress and hung their dead bodies for public display.

The victory at Stalingrad marked the beginning of the Soviet drive westward, during which the Soviets bore the brunt of the Nazi war machine. From the air, Britain and the United States bombed German cities, but it was an invasion from the west that Stalin wanted from his allies. Finally, on June 6, 1944, known as D-Day, the combined Allied forces, under the command of U.S. general Dwight Eisenhower, attacked the heavily fortified French beaches of Normandy and then fought their way through the German-held territory of western France. In late July, Allied forces broke through German defenses and a month later helped liberate Paris. The Soviets meanwhile recaptured the Baltic states and entered Poland, pausing for desperately needed supplies. The Germans took advantage of the pause to put down an uprising of the Polish resistance in August 1944, which gave the Soviets a freer hand in eastern Europe after the war. Facing more than twice as many troops as on the western front, the Soviet army took Bulgaria and Romania at the end of August, then Hungary in 1945. British, Canadian, U.S., and other Allied forces simultaneously fought their way eastward to join the Soviets in squeezing the Third Reich to its final defeat.

As the Allies advanced, Hitler decided that Germans deserved to perish. He thus refused all negotiations that might have spared them further death and destruction. As the Soviet army took Berlin, Hitler and his wife, Eva Braun, committed suicide. Although many soldiers remained loyal to the Third Reich, Germany finally surrendered on May 8, 1945.

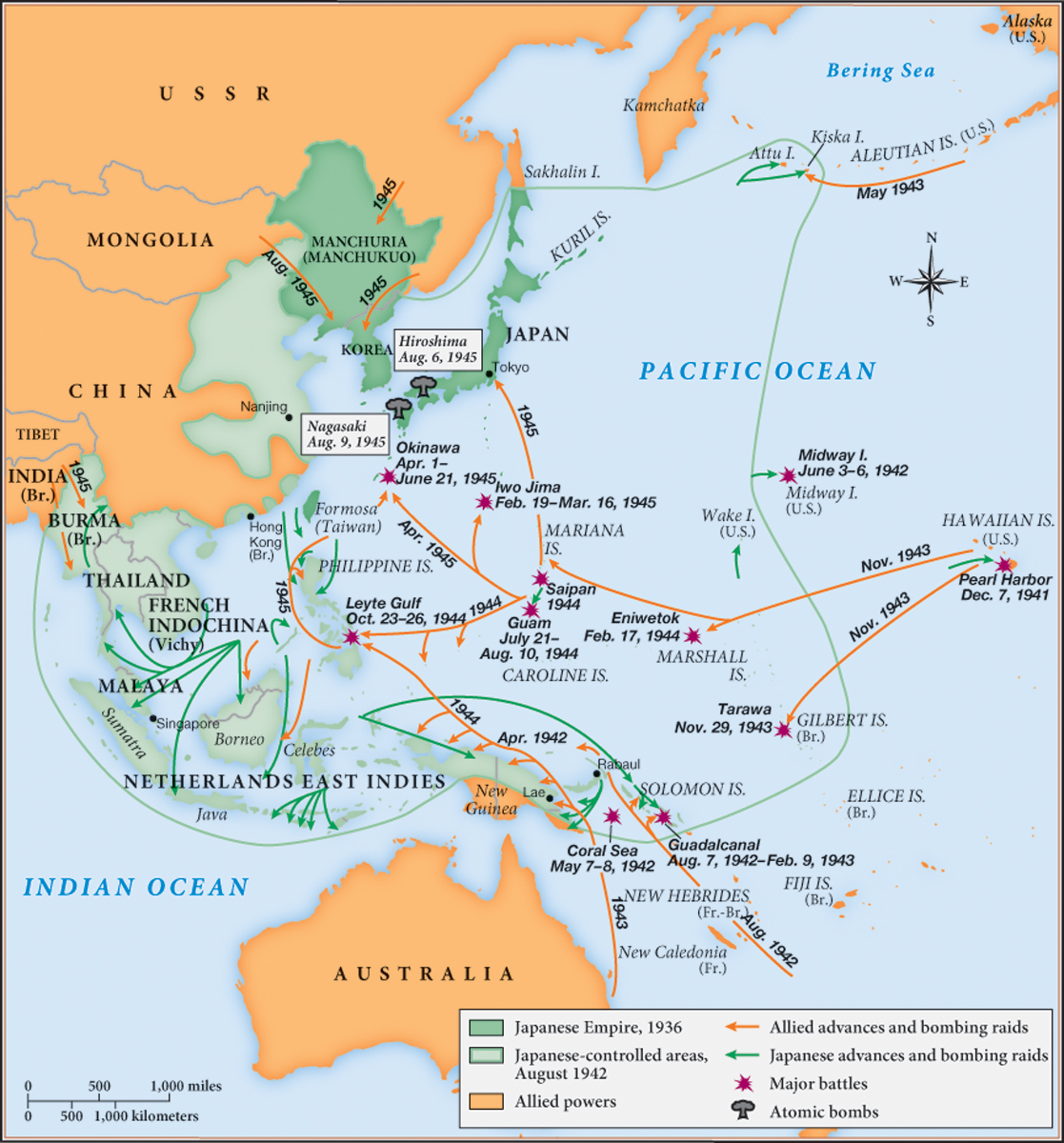

The Allies had followed a “Europe first” strategy in conducting the war. In 1940 and 1941, Japan had ousted the Europeans from many colonial holdings in Asia, but the Allies turned the tide in 1942 by destroying some of Japan’s formidable navy in battles at Midway Island and Guadalcanal (Map 26.5). Allied forces stormed one Pacific island after another, gaining bases from which to cut off the importation of supplies and to launch bombers toward Japan itself. Short of men and weapons, the Japanese military resorted to kamikaze tactics, in which pilots deliberately crashed their planes into Allied ships, killing themselves in the process. In response, the Allies stepped up their bombing of major cities, killing more than 100,000 civilians in their spring 1945 firebombing of Tokyo. The Japanese leadership still ruled out surrender.

Meanwhile a U.S.-based international team of more than 100,000 workers, including scientists and technicians, had been working on the Manhattan Project, the code name for a secret project to develop an atomic bomb. The Japanese practice of dying almost to the man rather than surrendering caused Allied military leaders to calculate that defeating Japan might cost the lives of hundreds of thousands of Allied soldiers (and even more Japanese). On August 6 and 9, 1945, the U.S. government therefore unleashed the new atomic weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing 140,000 people instantly; tens of thousands later died from burns, wounds, and other afflictions. Hardliners in the Japanese military wanted to continue the war, but on August 14, 1945, Japan surrendered.