Dealing with Nazism

Dealing with Nazism

In May 1945, the goals of feeding civilians, dealing with millions of refugees, purging Nazis, and setting up peacetime governments all needed attention. Governments-in-exile returned to reclaim power, but they often ran up against occupying armies that were a law unto themselves. The Soviets were especially feared for inflicting rape and robbery on Germans—abuses they justified by pointing to the tens of millions of worse atrocities committed by the Nazis. Adding to the sense of disorder was the lively trade in sex for food among starving civilians and well-supplied soldiers in all armies. Employing swift vigilante justice, civilians released pent-up rage and punished collaborators for their participation in genocide and occupation crimes. In France, villagers often shaved the heads of women suspected of associating with Germans and made some of them parade naked through the local streets. Members of the resistance executed tens of thousands of Nazi officers and collaborators without trial.

Allied representatives undertook what they claimed to be a systematic “denazification” that ranged from forcing German civilians to view the death camps to bringing to trial suspected local collaborators. The trials conducted at Nuremberg, Germany, by the victorious Allies in the fall of 1945 used the Nazis’ own documents to reveal a horrifying panorama of crimes by Nazi leaders. Although international law lacked any definition of genocide as a crime, the judges at Nuremberg found sufficient cause to impose death sentences on half of the twenty-four defendants, among them Hitler’s closest associates, and to give prison terms to the remainder. The Nuremberg trials introduced today’s notion of prosecution for crimes against humanity.

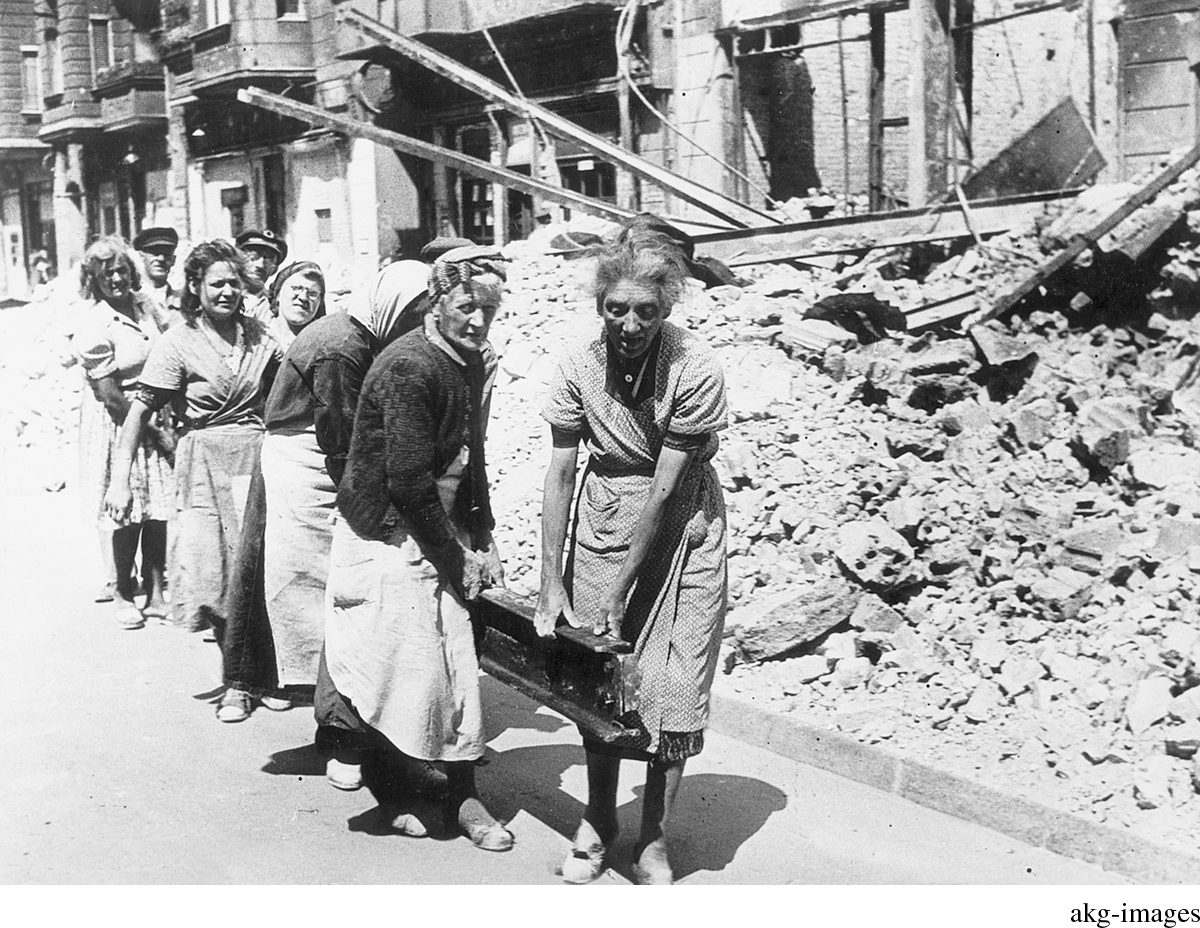

Allied prosecution of the Axis leadership was hardly thorough. Some of those most responsible for war crimes were not pursued, leaving many Germans skeptical about Allied intentions. As women in Germany faced violence at the hands of occupying troops, endured starvation, and were forced to do the rough manual labor of clearing rubble, Germans came to believe that they themselves were the main victims of the war. Distrust mounted when Allied officials, eager to restore government services and make western Europe more efficient than Soviet-controlled eastern Europe, began to hire former high-ranking Fascists and Nazis. Soon the new West German government proclaimed that the war’s real casualties were the German prisoners of war still held in Soviet camps.