New Nations in Africa

New Nations in Africa

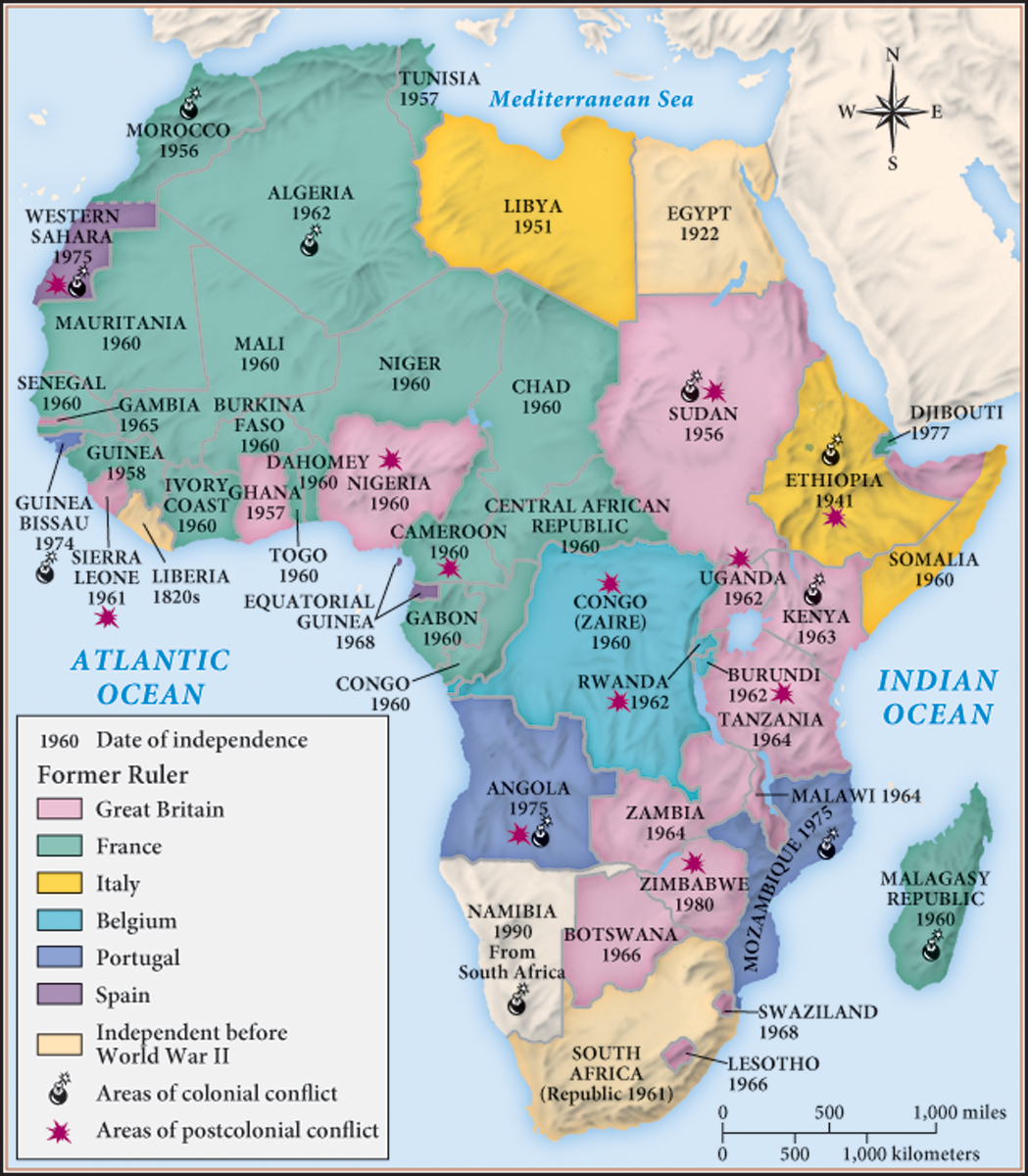

In sub-Saharan Africa, nationalist leaders roused their people to challenge Europe’s increasing demands for resources and labor—demands that resulted in poverty for African peoples. “The European Merchant is my shepherd, and I am in want,” went one African version of the Twenty-third Psalm. At the war’s end, veterans returned home and protest mounted. Kwame Nkrumah (1909–1972), for example, led the inhabitants of the British-controlled West African Gold Coast in Gandhi-inspired civil disobedience, finally driving the British out and bringing the state of Ghana into being in 1957. Nigeria, the most populous African region, achieved independence in 1960, and many other African states also became free (Map 27.5). (See “Contrasting Views: Decolonization in Africa.”)

In mixed-race territory with large settler populations, Europeans resisted giving up their control. In British East Africa, where white settlers ruled in splendor and where blacks lacked both land and economic opportunity, fighting erupted in the 1950s. African men formed rebel groups named Mau Mau but called by some the Land and Freedom Army. With women serving as provisioners, messengers, and weapon stealers, Mau Mau bands, composed mostly of war veterans from the Kikuyu ethnic group, tried to recover land from whites. In 1964, Mau Mau resistance helped Kenya gain formal independence, but only after the British had put hundreds of thousands of Kikuyus in concentration camps—called a “living hell” and a “British gulag” by those tortured there. The British slaughtered tens of thousands more.

France followed the British pattern of granting independence with relatively little bloodshed to territories such as Tunisia, Morocco, and West Africa, where there were few white settlers. In Algeria, however, which had one million settlers of European descent, the French fought bitterly to keep control. In the final days of World War II, the French army massacred tens of thousands of Algerian nationalists seeking independence; however, the liberation movement resurfaced with new intensity in 1954 as the Front for National Liberation (FNL). The French dug in and savagely tortured Algerian Arabs; Algerian women, shielded from suspicion by gender stereotypes, planted bombs in European cafés and carried weapons to assassination sites. (See “Document 27.2: Torture in Algeria.”) “The loss of Algeria,” warned one statesman, defending French savagery, “would be an unprecedented national disaster,” while the FNL, far less powerful and smaller in number, took its case to the court of world opinion. Reports of the French army’s barbarous practices against Algeria’s Muslim population prompted protests in Paris and around the globe, bringing wartime leader Charles de Gaulle to power in 1958. By 1962, de Gaulle had negotiated independence with the Algerian nationalists, and hundreds of thousands of Europeans in Algeria as well as their Arab supporters fled to France.

Violent resistance to the reimposition of colonial rule also ended the empires of the Dutch and Belgians. As newly independent nations emerged in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, structures arose to promote international security and worldwide deliberations, including representation from the new states. Foremost among these organizations was the United Nations (UN), convened for the first time in 1945. One notable change ensured the UN a greater chance of success than the League of Nations: both the United States and the Soviet Union were active members from the outset. The UN’s charter outlined a collective global authority that would resolve conflicts and provide military protection if any members were threatened by aggression. In 1955, the Indonesian president Sukarno, who had succeeded in wrenching Indonesian independence from the Dutch, sponsored the Bandung Convention of nonaligned nations to set a common policy for achieving modernization and facing the superpowers. Newly independent countries viewed the future with hope but still had to contend with the high costs of nation building and problems left over from decades of colonial exploitation.