A Changing Balance of World Power

A Changing Balance of World Power

Tested by protest at home, the superpowers found themselves facing a changing balance in world power. In the midst of turmoil, Henry Kissinger, Nixon’s secretary of state and a believer—like Otto von Bismarck—in Realpolitik, decided to take advantage of the ongoing rivalry between the USSR and China. After the Communist Revolution in 1949, Mao Zedong, China’s new leader, undertook foolish experiments in both manufacturing and agriculture that caused famine and massive suffering. As internal problems grew in both the Soviet Union and China, the two Communist giants skirmished along their shared borders and in diplomatic arenas. In 1972, President Nixon visited China, linking two very different great nations both facing disorder at home. Within China, Nixon’s visit helped slow the brutality and excesses of Mao’s regime. It also advanced the careers of Chinese pragmatists who were interested in technology and relations with the West and who laid the groundwork for China’s boom later in the century.

The diplomatic success of the visit led the Soviets to make their own overtures to the U.S.-led bloc, beginning a process known as détente (a relaxation of tensions). In 1972, the superpowers signed the first Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT I), which set a cap on the number of antimissile defenses each country could have. In 1975, in the Helsinki accords on human rights, the western bloc officially acknowledged Soviet territorial gains in World War II in exchange for the Soviet bloc’s guarantee of basic human rights.

Despite these successes, the war in Vietnam left the United States billions of dollars in debt to other countries and the international currency system in collapse. In the face of the resulting global economic chaos, Common Market countries united to force the United States to relinquish its single-handed direction of Western economic strategy. Another blow to U.S. leadership followed when it was revealed that Nixon’s office had threatened the U.S. system of free elections by authorizing the burglary and wiretapping of Democratic Party headquarters at Washington’s Watergate building during the 1972 presidential campaign. The Watergate scandal forced Nixon to resign in disgrace in the summer of 1974—one more weak spot in U.S. superpower status in the 1960s and 1970s.

The Middle East’s oil-producing nations dealt Western dominance still another major blow. Tensions between Israel and the Arab world provided the catalyst. In 1967, Israeli forces, responding to Palestinian guerrilla attacks, quickly seized Gaza and the Sinai peninsula from Egypt, the Golan Heights from Syria, and the West Bank from Jordan. Israel’s stunning victory in this action, which came to be called the Six-Day War, was followed in 1973 by a joint Egyptian and Syrian attack on Israel on Yom Kippur, the most holy day in the Jewish calendar. Israel, with material assistance from the United States, stopped the assault.

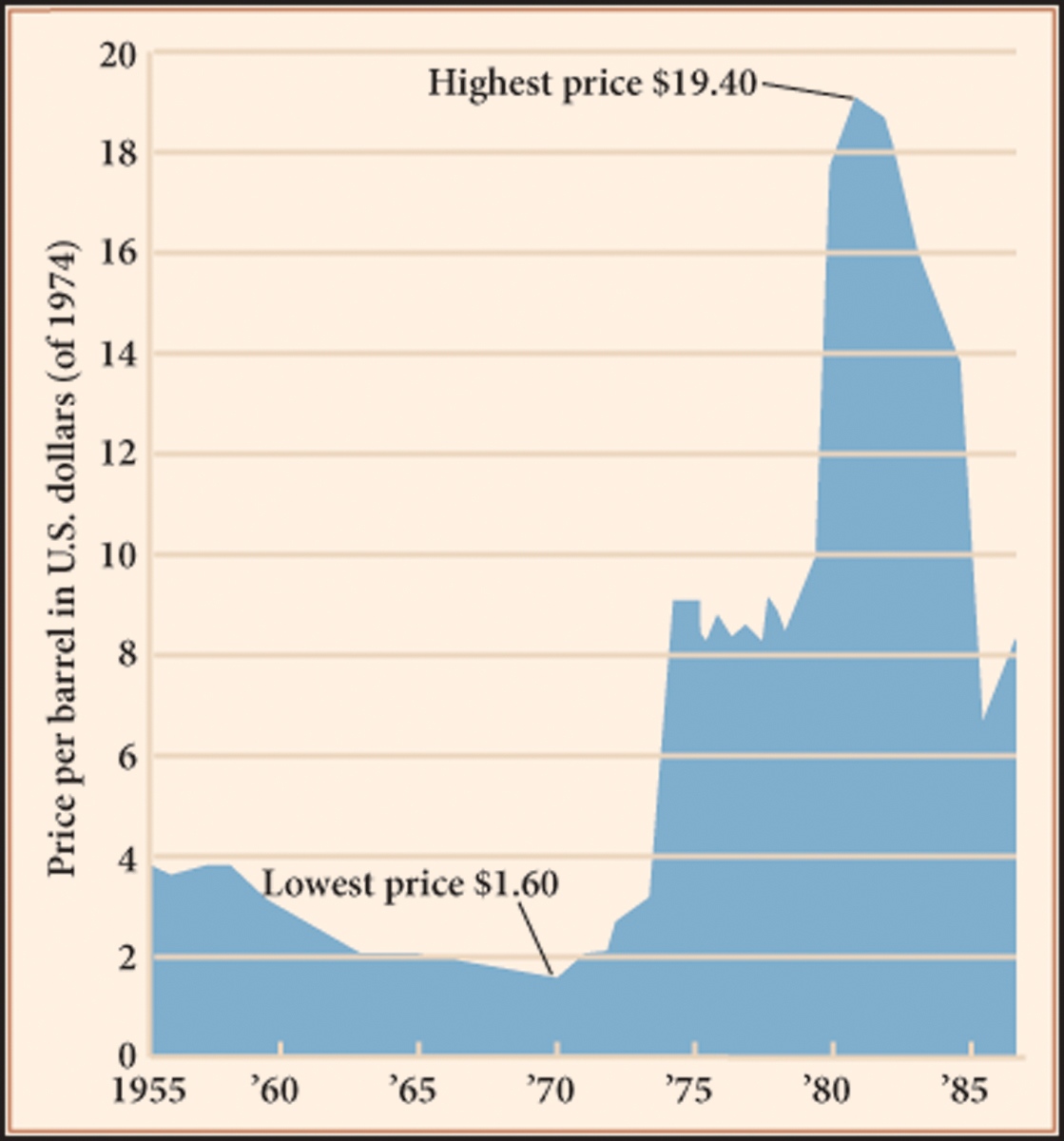

Having failed militarily, Arab nations in the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), a relatively loose consortium before the Yom Kippur War, combined to quadruple the price of their oil and impose an embargo, cutting off all exports of oil to the United States and its allies because they backed Israel. For the first time since imperialism’s heyday, the producers of raw materials—not the industrial powers—controlled the flow of commodities and set prices to their own advantage (Figure 28.1). As a result, unemployment rose by more than 50 percent in Europe and the United States and inflation soared. By the end of 1973, the inflation rate jumped to over 12 percent in France and 20 percent in Portugal. Eastern-bloc countries, dependent on Soviet oil, fared little better because the West could no longer afford their products and the Soviets boosted the price of their own oil. Skyrocketing interest rates discouraged both industrial investment and consumer buying. Prices, unemployment, and interest rates all rising created an unusual combination of economic conditions called stagflation. Western Europe drastically cut back on its oil dependence by undertaking conservation, enhancing public transportation, and raising the price of gasoline to encourage the development of fuel-efficient cars.

The U.S. bloc took further blows. In the late 1970s, students, clerics, shopkeepers, and unemployed men in Iran began an uprising that brought to power the Islamic ayatollah (a Shi‘ite religious leader) Ruhollah Khomeini (1902–1989). Using the new medium of audiocassette recordings to spread his message, Khomeini called for a transformation of Iran into a truly Islamic society, which meant the renunciation of the Western ways advocated by the American-backed shah, who was overthrown. In the autumn of 1979, supporters of Khomeini took hostages at the U.S. embassy in Teheran even as images of the captives’ stricken faces were sent around the globe via satellites. The United States was essentially paralyzed in the face of Islamic militancy, further OPEC price hikes, and a downwardly spiraling economy.