Collapse of Communism in the Soviet Bloc

Collapse of Communism in the Soviet Bloc

Beginning in 1985, reform came to the Soviet Union as well, but instead of fortifying the economy, it helped bring about the collapse of the Soviet bloc. The need for reform was evident. In 1979, the USSR became embroiled against Islam in Afghanistan when it supported a coup by a Communist faction against the government: casualties were 800,000 for the Soviets alone and 3 million for the Afghans. Further, global communications technology showed Soviet citizens that another way of life was possible. Citizens could see that the Soviet system of corrupt economic management produced a deteriorating standard of living. Shortages necessitated the three-generation household, in which grandparents took over tedious homemaking tasks from their working children and grandchildren, including waiting in long lines for basic commodities. “There is no special skill to this,” a seventy-three-year-old grandmother and former garbage collector remarked. “You just stand in line and wait.” One cheap and readily available product—vodka—pushed alcoholism to crisis levels, diminishing productivity and straining the nation’s morale.

In 1985, a new leader, Mikhail Gorbachev (1931–), opened an era of change. The son of peasants, Gorbachev had risen through Communist Party ranks as an agricultural specialist and had traveled abroad to observe life in the West. At home, he saw the consequences of economic stagnation: in much of the USSR, ordinary people decided not to have children. The Soviet Union was forced to import massive amounts of grain because 20 to 30 percent of the grain produced in the USSR rotted before it could be harvested or shipped to market, so great was the inefficiency of the state-directed economy. Industrial pollution had reached scandalous proportions because state-run enterprises cared only about meeting production quotas. A massive and privileged party bureaucracy feared innovation and failed to achieve socialism’s professed goal of a decent standard of living for working people. To match U.S. military growth, the Soviet Union diverted 15 to 20 percent of its gross national product (more than double the U.S. proportion) to armaments, further crippling the economy’s chances of raising living standards.

Gorbachev knew from experience and from his travels to western Europe that the Soviet system was completely inadequate, and he quickly proposed several unusual programs. A crucial economic reform, perestroika (“restructuring”), aimed to reinvigorate the Soviet economy by improving productivity, increasing investment, encouraging the use of up-to-date technology, and gradually introducing such market features as prices and profits. The complement to economic change was the policy of glasnost (usually translated as “openness” or “publicity”), which called for “wide, prompt, and frank information” and for allowing Soviet citizens new measures of free speech. When officials complained that glasnost threatened their status, Gorbachev replaced more than a third of the Communist Party’s leadership. The pressing need for glasnost became most evident after the Chernobyl catastrophe in 1986, when a nuclear reactor exploded and spewed radioactive dust into the atmosphere. Bureaucratic cover-ups delayed the spread of information about the accident, with lethal consequences for people living near the plant.

After Chernobyl, Communist Party meetings suddenly included complaints about the highest leaders and their policies. Television shows adopted the outspoken methods of American investigative reporting, and instead of publishing made-up letters praising the great Soviet state, newspapers were flooded with real ones complaining of shortages and abuse. One outraged “mother of two” protested that the cost-cutting policy of reusing syringes in hospitals was a source of AIDS, the deadly disease that had recently begun to spread worldwide. “Why should little kids have to pay for the criminal actions of our Ministry of Health?” she asked. Debate and factions arose across the political spectrum. In the fall of 1987, one of Gorbachev’s allies, Boris Yeltsin, quit the government after denouncing perestroika as insufficient to produce real reform. Yeltsin’s political daring inspired others to organize in opposition to crumbling Communist rule. In the spring of 1989, in a remarkably free balloting in Moscow’s local elections, not a single Communist was chosen.

Recognizing how severely the cold war arms race was draining Soviet resources, Gorbachev began scaling back missile production. His unilateral actions gradually won over Ronald Reagan. In 1985, the two leaders initiated a personal relationship and began defusing the cold war. “I bet the hard-liners in both our countries are bleeding when we shake hands,” said Reagan at the conclusion of one meeting. In early 1989, Gorbachev withdrew the last of his country’s forces from the debilitating war in Afghanistan, and the United States started to cut back its own vast military buildup.

As Gorbachev’s reforms in the USSR started spiraling out of his control, dissent was rising across the Soviet bloc. In the summer of 1980, Poles had gone on strike to protest government-increased food prices; workers at the Gdańsk shipyards, led by electrician Lech Walesa and crane operator Anna Walentynowicz, created an independent labor movement called Solidarity. The organization soon embraced much of the adult population, including a million members of the Communist Party. Both intellectuals and the Catholic church, long in the forefront of opposition to antireligious communism, supported Solidarity workers as they occupied factories in protest against the deteriorating conditions of everyday life. The members of Solidarity waved Polish flags and paraded giant portraits of the Virgin Mary and Pope John Paul II—a Polish native.

Global media coverage encouraged Solidarity leaders. As food became scarce and prices rose, tens of thousands of women joined in with marches, crying “We’re hungry!” They also protested working conditions, but as both workers and the only caretakers of home life, it was the scarcity of food that sent them into the streets. The Communist Party teetered on the edge of collapse, until the police and the army, with Soviet support, imposed a military government and in the winter of 1981 outlawed Solidarity. Using world communications networks, dissidents kept Solidarity alive and workers kept meeting, creating a new culture outside the official Soviet arts and newscasts. Poets read dissident verse to overflow crowds, and university professors lectured on such forbidden topics as Polish resistance in World War II. Activism in Poland and the news about it set the stage for communism’s downfall across the Soviet bloc.

The year 1989 saw uprisings around the world—in Chile, the Philippines, Haiti, South Africa, and China, for example. The global Cable News Network (CNN), established in 1980, linked many individual movements for democratic change through its twenty-four-hour coverage of world events. The most widely covered of these was the attack on the Communist state in China. Inspired by Gorbachev’s visit to Beijing, in the spring of 1989 thousands of Chinese students massed in the city’s Tiananmen Square, the world’s largest public square, to demand democracy. They used telex machines and e-mail to rush their messages to the international community, and they conveyed their goals through the cameras that Western television, broadcasting via satellite, trained on them. As workers began joining the pro-democracy forces, the government crushed the movement and executed as many as a thousand rebels.

News of the protests in Tiananmen Square was galvanizing to those in eastern Europe who were inspired in their long-standing tradition of resistance. In June 1989, the Polish government, weakened by its own bungling of the economy and lacking Soviet support for further repression, held free parliamentary elections. Solidarity candidates overwhelmingly defeated the Communists, and Walesa became president in early 1990. Gorbachev openly reversed the Brezhnev Doctrine, refusing to interfere in the political course of another nation. When it became clear that the Soviet Union would not intervene in Poland, the fall of communism repeated itself across the Soviet bloc.

Communism had collapsed in Poland; it then collapsed in Hungary, in part because Hungarians, too, had experimented with “market socialism” since the 1960s. Hungarian citizens were already protesting the government, lobbying, for example, against ecologically unsound projects like the construction of a new dam. They encouraged boycotts of Communist holidays, and on March 15, 1989, they boldly commemorated the anniversary of the Hungarian uprising. These popular demands for liberalization led the parliament in the fall of 1989 to dismiss the Communist Party as the official ruling institution.

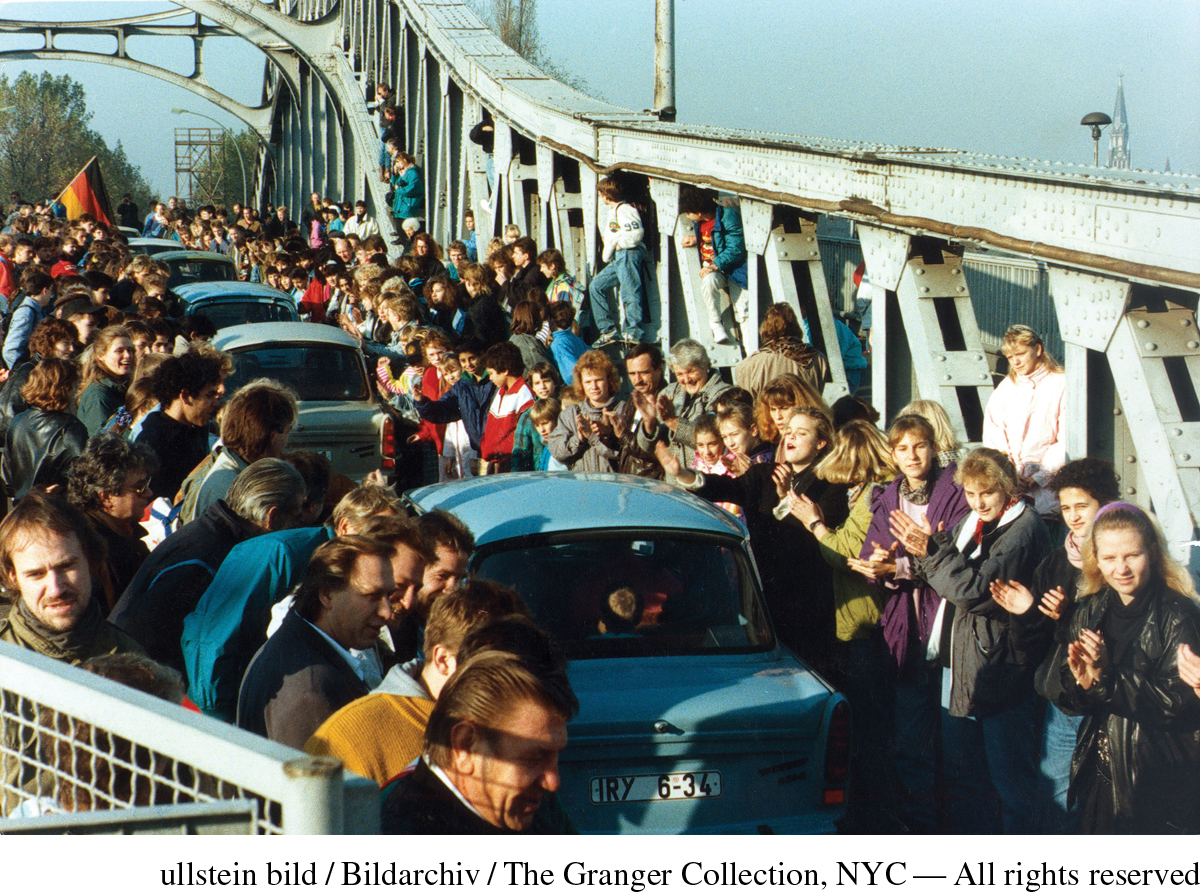

The most potent symbol of a divided Europe was the Berlin Wall, and East Germans had attempted to escape over it for decades. In the summer of 1989, crowds of East Germans flooded the borders to escape the crumbling Soviet bloc, and hundreds of thousands of protesters rallied throughout the fall against the regime. Satellite television brought them visions of postindustrial prosperity and of free and open public debate in West Germany. Crowds of demonstrators greeted Gorbachev, taken as a hero by many, when he visited the country in October. On November 9, guards at the Berlin Wall allowed free passage to the west, turning protest into a festive holiday. As they strolled freely in the streets, East Berliners saw firsthand the goods available in a successful postindustrial society. Soon thereafter, citizens—east and west—released years of frustration by assaulting the Berlin Wall with sledgehammers.

In Czechoslovakia people also watched televised news of glasnost expectantly. Persecuted dissidents had maintained their critique of Communist rule. In an open letter to the Czechoslovak Communist Party leadership, playwright Václav Havel accused Marxist-Leninist rule of making people materialistic and indifferent to public life. In 1977, Havel, along with a group of fellow intellectuals and workers, signed Charter 77, a public protest against the regime that resulted in the arrest of the signers. In the mid-1980s, they and the wider population heard Gorbachev on television calling for free speech. Protesters clamored for democracy, but the government turned the police on them, arresting activists in January 1989 for commemorating the death of Jan Palach. The turning point came in November 1989 when, in response to police beatings of students, Alexander Dubček, leader of the Prague Spring of 1968, addressed the crowds in Prague’s Wenceslas Square with a call to oust the Stalinists from the government. Almost immediately, the Communist leadership resigned. Capping what became known as the “velvet revolution” for its lack of bloodshed, the formerly Communist-dominated parliament elevated Havel to the presidency.

REVIEW QUESTION How and why did the balance of world power change during the 1980s?

From the mid-1960s on, Nicolae Ceauşescu had ruled Romania as the harshest dictator in Communist Europe since Stalin. In the name of modernization, he destroyed whole villages; to build up the population, he outlawed contraceptives and abortions, a restriction that led to the abandonment of tens of thousands of children. He preached the virtues of a very slim body so that he could cut rations and use the savings for buying private castles and building himself an enormous palace in Bucharest. To this end, he tore down entire neighborhoods and dozens of historical buildings and crushed opponents of the gaudy project to make it appear popular. Yet in early December 1989, workers demonstrated against the dictatorial government, and the army turned on Ceauşescu loyalists. On Christmas Day, viewers watched on television as the dictator and his wife were tried by a military court and then executed. For many, the death of Ceauşescu meant that the very worst of communism was over.