Radical Islam Meets the West

Radical Islam Meets the West

North–South antagonisms became evident in the rise of radical Islam, which often flourished where democracy and prosperity for the masses were missing. The Iranian hostage crisis that began in 1979 revealed nationalism and a strong anti-Western sentiment among Islamic fundamentalists. The charismatic leaders of the 1980s and 1990s—the ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in Iran, Libya’s Muammar Qaddafi, Iraq’s Saddam Hussein, and Osama bin Laden, a Saudi Arabian by birth and leader of the transnational terrorist organization al-Qaeda—variously promoted a pan-Islamic or (outside Iran) pan-Arabic world order that gathered increasing support. Khomeini’s program—“Neither East, nor West, only the Islamic Republic”—had wide appeal even after his death in 1989. Renouncing the Westernization that had flourished under the shah, Khomeini began a regime in Iran that required women once again to cover their bodies almost totally in special clothing, restricted their access to divorce, and eliminated a range of other rights for men and women alike. Buoyed by the prosperity that oil had brought and following Khomeini’s lead, Islamic revolutionaries across the wider region aimed to restore the pride and Islamic identity that imperialism had stripped from Middle Eastern men.

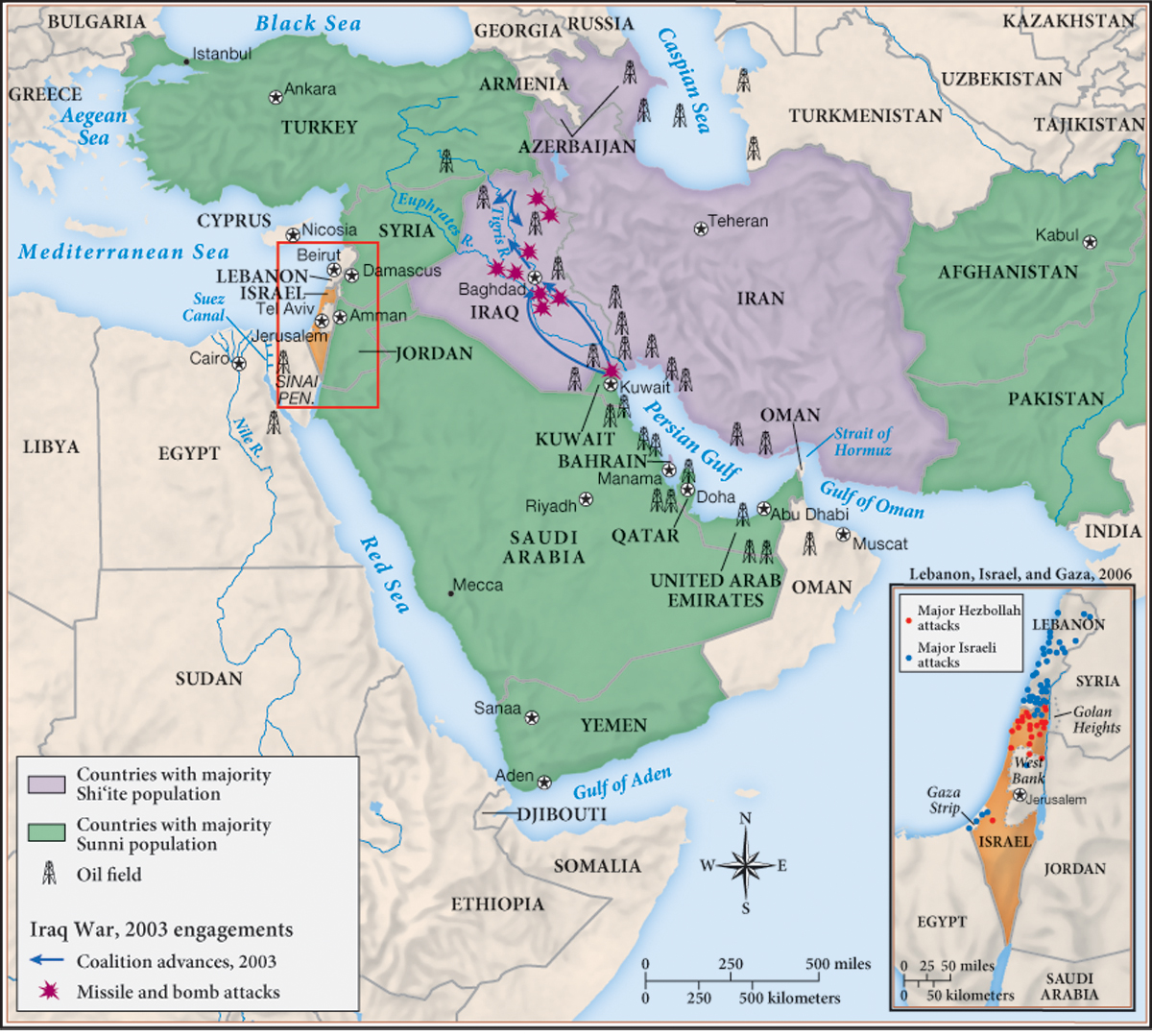

Power in the Middle East remained fragmented, however, as war plagued the region. In 1980, Saddam Hussein, fearing a rebellion from Shi‘ites in Iraq, attacked Iran in hopes of channeling Shi‘ite discontent into a patriotic crusade against non-Arab Iranians. The United States provided Iraq with massive aid in the struggle against Iran, but eight years of combat, with extensive loss of life on both sides, ended in stalemate. In 1990, Saddam tested the post–cold war waters by invading neighboring Kuwait in hopes of annexing the oil-rich country to debt-ridden Iraq. A United Nations coalition led by the United States stopped the invasion and defeated the Iraqi army, but discontent mounted in the region (Map 29.4).

To the east, the Taliban—a militant Islamic group initially funded by the United States, China, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan during the cold war—took over the government of Afghanistan in the late 1990s. Its leaders imposed a regime that forbade girls from attending schools and women from leaving their homes without a male escort and demanded from men strict adherence to its rules for dress.

To the west, conflict between the Israelis and the Palestinians continued. As Israeli settlers took more Palestinian land and homes, Palestinian suicide bombers began murdering Israeli civilians in the late 1990s. The Israeli government retaliated with missiles, machine guns, and tanks, often killing Palestinian civilians in turn. In 2006, the Israelis, responding to the political militia Hezbollah’s kidnapping of Israeli soldiers, attacked Lebanon, destroying infrastructure, sending missiles into its capital city of Beirut, and killing hundreds of civilians. Beginning in the 1980s and continuing into the 2000s, terrorists from the Middle East and North Africa planted bombs in European cities, blew airplanes out of the sky, and bombed the Paris subway system. These attacks were said to be punishment for the West’s support both for Israel and for Middle Eastern dictatorships.

On September 11, 2001, the ongoing terrorism in Europe and around the world caught the full attention of the United States when Muslim militants hijacked four planes in the United States and flew two of them into the World Trade Center in New York City and one into the Pentagon in Virginia. The fourth plane, en route to the Capitol, crashed in Pennsylvania when passengers forced the hijackers to lose control of the aircraft. The hijackers, most of whom were from Saudi Arabia, were inspired by the wealthy radical leader of al-Qaeda, Osama bin Laden, who sought to end the presence of U.S. forces in Saudi Arabia. They had trained in bin Laden’s terrorist camps in Afghanistan and learned to pilot planes in the United States. The loss of more than three thousand lives led the United States to declare a “war against terrorism.” The administration of U.S. president George W. Bush forged a multinational coalition, which included the vital cooperation of Islamic countries such as Pakistan, with the main goal of driving the ruling Taliban out of Afghanistan.

At first, the September 11 attacks and other lethal terrorist attacks around the world promoted global cooperation. European countries rounded up suspected terrorists and conducted the first successful trials of them in the spring of 2003. Ultimately, however, the West became divided when the United States claimed that Saddam Hussein was concealing weapons of mass destruction in Iraq and suggested ties between him and bin Laden’s terrorist group. Great Britain, Spain, and Poland were among those who joined the coalition of invading forces, but some powerful European states—including Germany, Russia, and France—refused, sparking the anger of many Americans, some of whom sported bumper stickers with the demand “First Iraq, Next France” or participated in happy hours devoted to “French bashing.”

U.S. war fever mounted with the suggestion that Syria and Iran should also be invaded, while the rest of the world condemned what seemed a sudden American blood lust. Europeans in general, including the British public, accused the United States of becoming a world military dictatorship to preserve its only remaining value—wasteful consumerism. The United States countercharged that the Europeans were too selfishly enjoying their democracy and creature comforts to help fund the military defense of freedom under attack. The Spanish withdrew from the U.S. occupation of Iraq after terrorists linked to al-Qaeda bombed four Madrid commuter trains on March 11, 2004. The British, too, reeled when terrorists exploded bombs in three subway cars and a bus in central London in July 2005. Barack Obama, who was elected the first African American U.S. president in 2008, brought home all the troops from Iraq in 2012, though the United States maintained a presence there of military advisers. As for al-Qaeda, the United States weakened the organization by assassinating top leaders, including Osama bin Laden in 2011.