Urban Culture Regions

Urban Culture Regions

How are areas within a city spatially arranged? Much of the fascination with urban life comes from its diversity, from the excitement created by different groups of people and different types of activities packaged in a fairly small area. Yet within this diversity, it is possible to discern regional patterns, for cities are composed of a series of districts, each of which is defined by a particular set of land uses.

Downtowns

Downtowns

central business district (CBD) The central portion of a city, characterized by high-density land uses.

In the center of the typical city is the central business district (CBD), a dense cluster of offices and shops. The CBD is formed around the point within the city that is most accessible. As such, businesses and services in the CBD experience the most action as measured by the volume of people, money, and ideas moving through this space. Competition for this space often leads to the construction of skyscrapers, creating a skyline that characterizes and symbolizes a city’s CBD and the activities that are often located there: financial services, corporate headquarters, and related services such as advertising and public relations firms. The tallest buildings in the world are located in Asian cities such as Shanghai, Kuala Lumpur, and Taipei—cities that are vying to be major financial centers (Figure 11.1). Just beyond the skyscrapers are often four- and five-story buildings that make up the city’s main shopping district, traditionally centered on several department stores. Also within the CBD are concentrations of smaller retail establishments, transportation hubs such as railroad stations, and often civic centers such as a city hall and main library. Surrounding the CBD is a transitional zone, because it is situated between the core commercial area and the outlying residential areas. It is a district of mixed land uses, characterized by older residential buildings, warehouses, small factories, and apartment buildings.

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.1

ozIQn8o4oubO2kYO0hTrLOpalJEoknPJpVEOaLRB2H6SaguEgtEDWVWQmAycra6FPyyt+/V8EGOQET4WhMRtcS/gVOalaUE9nq+lxiHyIHGwccIvHrtLxdfmkVZfeLiXResidential Areas and Neighborhoods

Residential Areas and Neighborhoods

social culture region An area in a city where many of the residents share social traits such as income, education, age, and family structure.

ethnic culture region An area occupied by people of similar ethnic background who share traits of ethnicity, such as language and migration history.

Beyond the transitional zone are various types of residential communities, or regions. Geographers have studied these culture regions in depth, trying to discern patterns of the distribution of diverse peoples. Some have focused on the idea of a social culture region: a residential area characterized by socioeconomic traits, such as income, education, age, and family structure (Figure 11.2 and Figure 11.3). Other researchers, who use the notion of ethnic culture region, highlight traits of ethnicity, such as language and migration history. Obviously the two concepts overlap, because social regions can exist within ethnic regions and vice versa. In addition, some researchers treat both social and ethnic culture regions as functions of the political and economic forces underlying and reinforcing residential segregation and discrimination. (More information on ethnic areas is found in Chapter 5.)

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.2

K69HHAGh4cWNsPVuU9OUB+x17qCJ+qW8i+BhBRpqZQUBvJ6YgZgDPjQhnv2EZ4rw3h61EEqdTzK1Tu/H1/BB81Dki0D/VPRA

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.3

GLXA/f7KB+ze7bZUu6DqBZ6PxcHrpjavwM/3Bq5fkt0Mi6nUoULR2LwDcPTqKXHKFSCOtbVq7Vhnann+/0LHWm+8H3pOBAJ/w4SQuOaaKn6/01n8J+nbSn3rc1i7u7Sgk02Spac4Ix8M2Cu5303

census tract A small district used by the U.S. Census Bureau to survey the population.

One way to define social culture regions is to isolate one social trait, such as income, and plot its distribution within the city. The U.S. census is a common source of such information because the districts used to count population, called census tracts, are small enough to allow the subtle texture of social regions to show. These maps of social traits form the basis of many urban land-use models, which we discuss later in this chapter.

Ethnicity often distinguishes one urban residential area from another. This is not surprising, given the history of immigration to North America and the propensity of immigrants to move to cities. During the middle to late nineteenth century, when waves of immigrants left eastern and southern Europe, North American port cities were a common destination, and employment as laborers in factories was the norm. With limited affordable housing available, most immigrants settled close to one another, forming ethnic communities or pockets within the mosaic of the city. These ethnic urban regions—with names such as Little Italy and Chinatown—often allowed the immigrants to maintain their native languages, holidays, foodways, and religions. Although the names of these urban enclaves still exist today, most of them have been transformed by new and different waves of immigrants arriving in North America in the past 20 years (Figure 11.4). New York’s Little Italy, for example, is now home to people from East and Southeast Asia, with Italian restaurants vying for space with noodle houses.

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.4

PVPxg5cz2qw1Uy+loslOXd6hRhL4RIHcZz9XS9Mlm2n4bvyWLNpDzr7ExVgYDllJnqrusJwvbA6cL4+6a0h2YvkqgfbaQvBhHONry+YUHVoUlj/7nzp3+eE9y9NonOz5kNEgNkCToRjMTPgJykobBjVLicrt5oNjDBVaZwGqNDd5GWCZSIPq4iYnPkEfjJlbVd/e+3ttEAc=Reflecting on Geography

Question 11.5

XrDxT/o/Mdem+utjijLumSjPDaYx3IQqYlEf+zchaoZW9ZRO7YPvMvjrBWzMS6A1GGC0YDt0h0RfZelcsqmcRt5oVQlcc+d99qJm17Qv36FSXacG513GcgTl8xKT4CGFDSklJzfs37M5UdEjIhKnlwZ21yO+qkry4+uFIhoK4PsiPsJjZElL1/DPI3IuJhppimBLE1cz1gWCtZTsspQU9Ww5achmQwzdvglPJ94uOTOu07OIxCWEup9aLdmA2mb0AIGMytqyhLp4eQ0Eneighborhood A small social area within a city where residents share values and concerns and interact with one another on a daily basis.

Social culture regions are not merely statistical definitions. They are also areas of shared values and attitudes, of interaction and communication. Neighborhood is a concept often used to describe small social culture regions where people with shared values and concerns interact daily. For example, if we consider only census figures, we might find that parents between 30 and 45 years of age with two or three children and earning between $65,000 and $90,000 a year cover a fairly wide area in any given city. Yet, from our own observations, we know intuitively that this broad social area is probably composed of numerous neighborhoods where people associate a sense of community with a specific locale.

304

A conventional sociological explanation for neighborhoods is that people of similar values cluster together to reduce social conflict. Where a social consensus exists about such mundane issues as home maintenance, child rearing, acceptable behavior, and public order, there is little daily worry about these matters. People who deviate from this consensus will face social coercion that could force them to seek residence elsewhere, thus preserving the values of the neighborhood. However, many neighborhoods have more heterogeneity than this traditional definition would allow. Although a neighborhood might be ethnically and socially diverse, its residents may think of themselves as a community that shares similar political concerns, holds neighborhood meetings to address these problems, and achieves recognition at city hall as a legitimate group with political standing.

Homelessness

Homelessness

homelessness A temporary or permanent condition of not having a legal home address.

Neighborhoods are usually composed of people who have access to a permanent or semipermanent place of residence. In the cities of the United States, however, homelessness, and with it the loss of neighborhood, is increasingly common. It is nearly impossible to determine the exact number of homeless people in the United States because definitions of homelessness vary. For example, does living in a friend’s house for more than a month constitute a homeless condition? How permanent does a shelter have to be before it is considered a home? To some people, home connotes a suburban middle-class house; to others, it simply refers to a room in a city-owned shelter.

Reflecting on Geography

Question 11.6

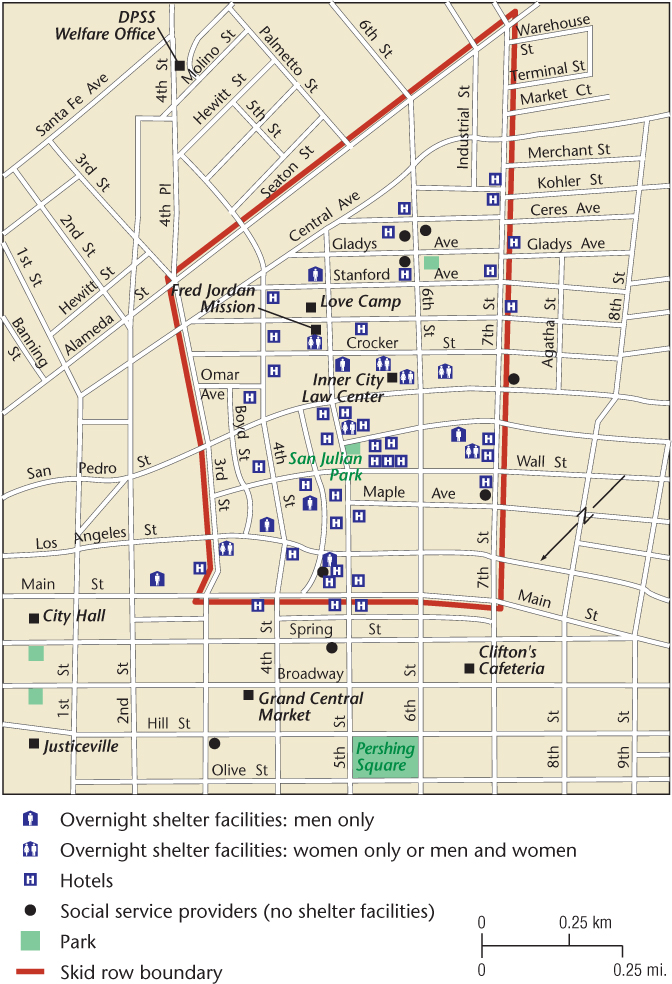

uWoqcuwqKxlzDm+1+SZxg8Dkm1bEX42zuvTUhgiVsjeHOdZu37jEjog8f2RzHaH8BIGKLVf48PUOFGiDRT4YMohJvd8IbCctFd6w1t8+bNNZHOPTXtnt+5L76oWAEOr/mm94GYdNhR1KESqLz3hcfg==Recent studies suggest that there are up to 3 million homeless people in the United States, concentrated in the downtown areas of large cities, often in what we call the transitional zone. The causes of homelessness are varied and complex. Many homeless people suffer from some type of disorder or handicap that contributes to their inability to maintain a job and obtain adequate housing. Deprived of the social networks that a permanent neighborhood provides, the homeless are left to fend for themselves. Most cities have tried to provide temporary shelter, but many homeless people prefer to rely on their own social ties for support to maintain some sense of personal pride and privacy. In a study of the Los Angeles skid row district, Stacy Rowe and Jennifer Wolch explored how homeless women formed new types of social networks and established a sense of community to cope with the day-to-day needs of physical security and food (Figure 11.5).

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.7

ejgJxVLNbLXGLI9xHUAURdr+eenwW1u1UwaHcGDII7Wt/IdrJKfX6M5v6X6cQGscS8EEhAhS40I7VKloCr7srZZPKhceF7qnyslBUh4lD+PNqzkx7H7c7TIm5FubZrxap1F1r3cCTTc/iKllO5pEV7ceWSDWJ1eVpRSNqM7q2t1SZFyLFqOSdw==305