Cultural Diffusion

Cultural Diffusion

cultural diffusion The spread of elements of culture from the point of origin over an area.

Regardless of type, the culture regions of the world evolved through communication and contact among people. In other words, they are the product of cultural diffusion, the spatial spread of learned ideas, innovations, and attitudes throughout an area. The study of cultural diffusion is a very important theme in cultural geography. Through the study of diffusion, cultural geographers can begin to understand how spatial patterns in culture evolved.

independent invention A cultural innovation that is developed in two or more locations by individuals or groups working independently.

After all, any culture is the product of almost countless innovations that spread from their points of origin to cover a wider area. Some innovations occur only once, and geographers can sometimes trace a cultural element back to a single place of origin. In other cases, independent invention occurs: the same or a very similar innovation is separately developed at different places by different people.

Types of Diffusion

relocation diffusion The spread of an innovation or other element of culture that occurs with the bodily relocation (migration) of the individual or group responsible for the innovation.

expansion diffusion The spread of innovations within an area in a snowballing process so that the total number of knowers or users becomes greater and the area of occurrence grows.

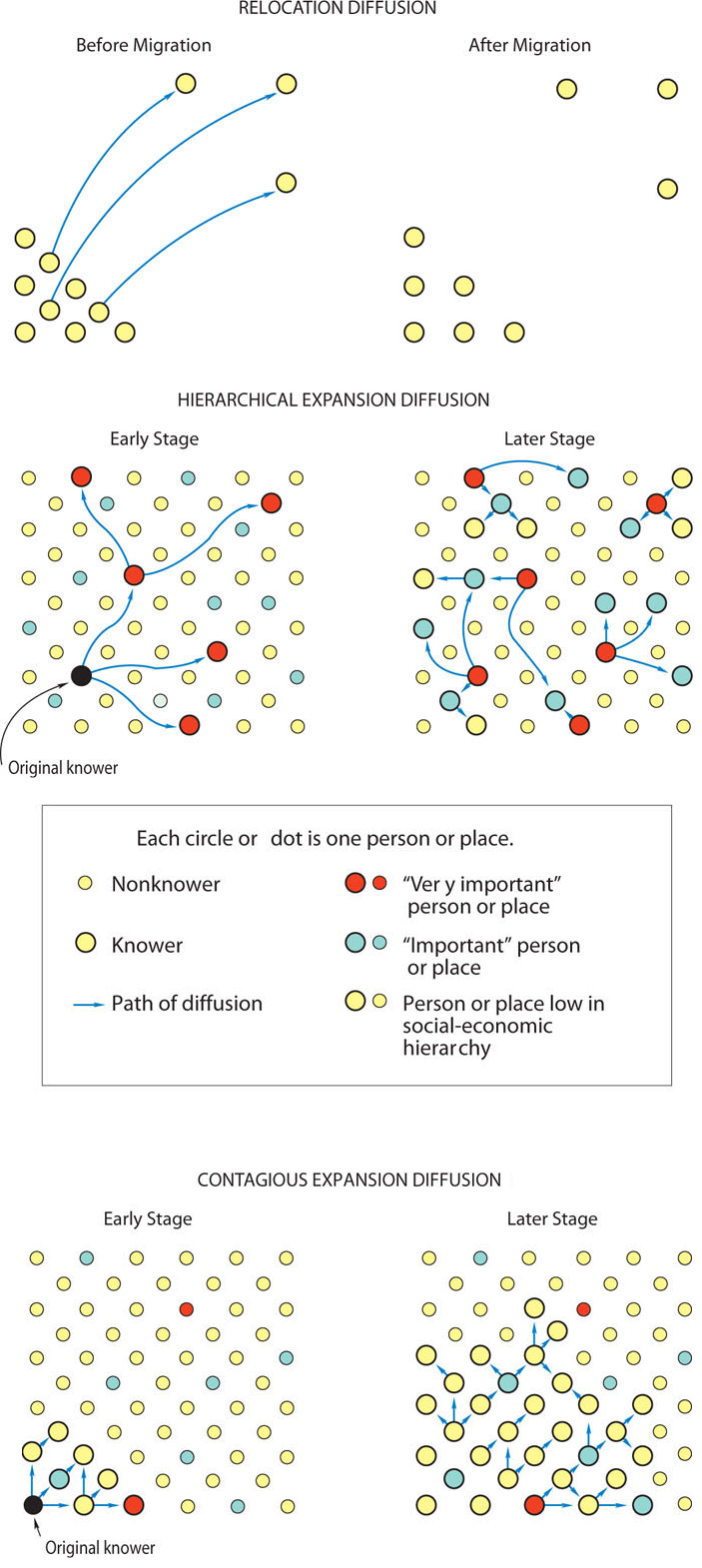

Types of Diffusion Geographers, drawing heavily on the research of Torsten Hägerstrand, recognize several different kinds of diffusion (Figure 1.10). Relocation diffusion occurs when individuals or groups with a particular idea or practice migrate from one location to another, thereby bringing the idea or practice to their new homeland. Religions frequently spread this way. An example is the migration of Christianity with European settlers who came to America. In expansion diffusion, ideas or practices spread throughout a population, from area to area, in a snowballing process, so that the total number of knowers or users and the areas of occurrence increase.

Thinking Geographically

Question

uocH5M0+1HApQxBLM2rj/Xd8gylGkPKBAIIko29wrmdHwbrPgtuoFCl2vQUcvjDgzPnDVxatSltk703LdUoZoBI1rACYIu98XJEyZy7dwQxIh6DUO41QzIgCdzir/N3nxY33MyEYO6ufikMgwe6yyy9tpUKddvE2eEljIEShoc6dfTHXyZufChjj198WgMwFhierarchical diffusion A type of expansion diffusion in which innovations spread from one important person to another or from one urban center to another, temporarily bypassing other persons or rural areas.

contagious diffusion A type of expansion diffusion in which cultural innovation spreads by person-to-person contact, moving wavelike through an area and population without regard to social status.

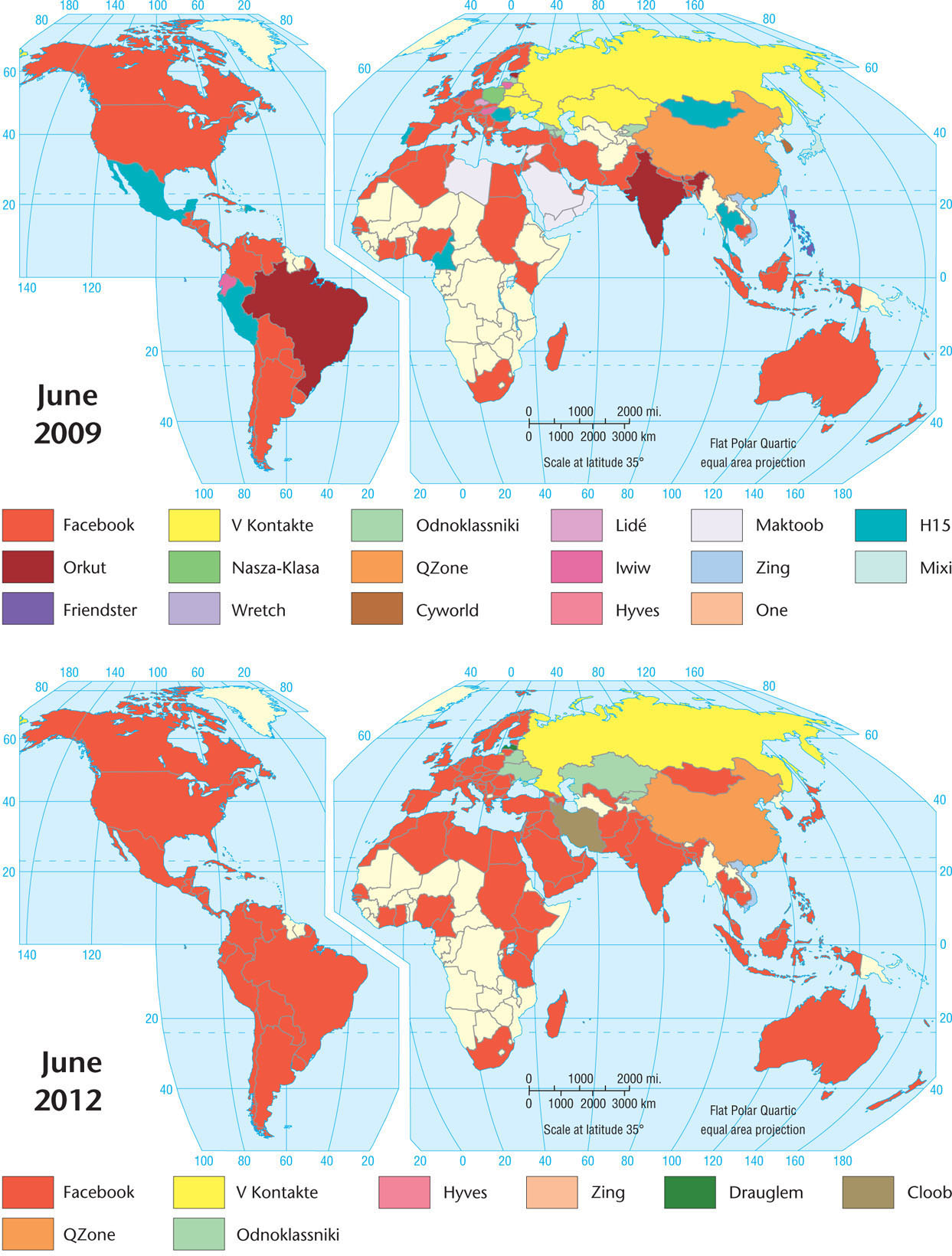

Expansion diffusion can be further divided into three subtypes. In hierarchical diffusion, ideas leapfrog from one important person to another or from one urban center to another, temporarily bypassing other persons or rural territories. We can see hierarchical diffusion at work in everyday life by observing the acceptance of new modes of dress or foods. For example, sushi restaurants originally diffused from Japan in the 1970s very slowly because many people were reluctant to eat raw fish. In the United States, the first sushi restaurants appeared in the major cities Los Angeles and New York. Only gradually throughout the 1980s and 1990s did sushi eating become more common in the less urbanized parts of the country. By contrast, contagious diffusion is the wavelike spread of ideas in the manner of a contagious disease, moving throughout space without regard to hierarchies. Hierarchical and contagious diffusion often work together. The global spread of social networking provides an example of how these two types of diffusion can reinforce each other. As you can see in Figure 1.11, the use of Facebook had spread throughout much of the world by 2009. This diffusion took place first through a hierarchical process wherein the student inventors of Facebook granted access only to fellow students at Harvard University and to other universities in the Boston area. Access was then granted to other Ivy League universities that were hierarchically linked to Harvard. Soon, however, open access was granted and contagious diffusion processes took over. Interest in the site then spread through word of mouth to the rest of the United States and throughout the world.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Aly06vYF2/UWxh5DM47n36YhiKjrzo7EA+jfVoU6cJq6u4sqn7kQ6BZu0m/tz1AJ1aghKn6qobeTVI7ZSIRoh7FC/Zb9Ldz7uJ37eDF085F0HT6HZ2iQNNQiG1t7zzNMDk1cDnMXH6JdiPiyTbBILriI0NqYpZToDSZgRA==stimulus diffusion A type of expansion diffusion in which a specific trait fails to spread but the underlying idea or concept is accepted.

Sometimes a specific trait is rejected but the underlying idea is accepted, resulting in stimulus diffusion. For example, early Siberian peoples domesticated reindeer only after exposure to the domesticated cattle raised by cultures to their south. The Siberians had no use for cattle, but the idea of domesticated herds appealed to them, and they began domesticating reindeer, an animal they had long hunted.

12

In recent decades, all types of cultural diffusion have been affected by advances in communication technology, especially the Internet. The Internet has dramatically changed the rate at which cultural information and ideas can be exchanged between people all over the world without in-person contact. For example, in an instant, a musician or band can share a video on YouTube; clothing and other trendy items can be purchased from far-off locations where new styles are emerging; and political ideas can be exchanged and debated on blogs read by people living under different forms of government. In addition to the Internet, an increase in cellular phone usage has expanded communication, resulting in the development of “text speak,” wherein people converse in a new language of acronyms that have even begun to be published in texting dictionaries (LOL, laughing out loud; TTYL, talk to you later).

cybergeography A branch of geography that studies the Internet as a virtual place. Cybergeographers examine locations in cyberspace as sites of human interaction with structures that can be mapped.

These new electronic exchanges have inspired geographers to consider how cultural diffusion occurs today as compared to in the past. In a new branch of geography called cybergeography, scholars study the structure of the Internet and how people interact on it. They examine how technology is changing cultural diffusion and map online spaces. Here are some examples of recent cybergeographic research:

- Steve Jones has examined how music is increasingly reaching people via the Internet.

- Sarah Holloway and Gill Valentine have conducted a study of British children’s use of the Internet and how these young people adopt “Americanized” trends and ideas as a result of this interaction.

- Eric Gordon in the United States has edited a special edition of the journal Space and Culture that focuses on virtual worlds, like Second Life, and how they aid cultural diffusion.

time-distance decay The decrease in acceptance of a cultural innovation with increasing time and distance from its origin.

While cybergeographic research focuses on cultural diffusion since the advent of the Internet, geographers have long been concerned with the spread of cultural innovation and have devised theories to explain these processes. Geographers have described the spread of new ideas as being similar to throwing a rock into a pond and watching the spread of ripples. You can see the ripples become gradually weaker as they move away from the point of impact. In the same way, diffusion was thought to become weaker as a cultural innovation moves away from its point of origin. Therefore, diffusion was thought to decrease with distance, with innovations usually being accepted most thoroughly in areas closest to their origin. Time was also considered a factor, because in the past innovations often took more time to diffuse the farther they spread from the origin. This general decrease of acceptance of cultural innovation with both increasing distance and time produced what geographers call time-distance decay. However, the Internet and other contemporary forms of mass communication have greatly accelerated diffusion, diminishing the impact of time-distance decay.

absorbing barrier A barrier that completely halts diffusion of innovations and blocks the spread of cultural elements.

In addition to the gradual weakening or decay of an innovation through time and distance, barriers can retard its spread. Absorbing barriers completely halt diffusion, allowing no further progress. For example, in 1998, the fundamentalist Islamic Taliban government of Afghanistan decided to abolish television, videocassette recorders, and videotapes, viewing them as causes of corruption in society. As a result, the cultural diffusion of television sets was reversed, and the important role of television as a communication device to facilitate the spread of ideas was eliminated.

permeable barrier A barrier that permits some aspects of an innovation to diffuse through it but weakens and retards continued spread. An innovation can be modified in passing through a permeable barrier.

Extreme examples aside, few absorbing barriers exist in the world. More commonly, barriers are permeable, allowing part of the innovation wave to diffuse through but acting to weaken or retard the continued spread. When a school board objects to students with tattoos or body piercings, the principal of a high school may set limits by mandating that these markings be covered by clothing. However, over time, those mandates may change as people get used to the idea of body markings. More likely than not, though, some mandates will remain in place. In this way, the principal and the school board act as a permeable barrier to cultural innovations.

With advances in communication technology, new types of permeable barriers are emerging. For example, electronic permeable barriers can be found in some states whose governments have prevented access to Internet sites that criticize their policies. Countries with Internet censorship include China, Saudi Arabia, and Iran. In these (and other) countries, individuals’ Internet use is sometimes monitored to prevent communications that the government believes may lead to social unrest or organized protest movements. Censorship and monitoring can be considered permeable barriers that restrict the spread of certain ideas while allowing other types of information to diffuse.

13

Reflecting on Geography

Question

3LMRLREJE6hrxwWsbrH+BSuNMai6JK1b0Zj5vjPLw8Udslgh6iYNqv/X05P8XhYWw8KSI+6dhiqabqA+06qjs7h1wmVzRXNnOseNqEKvCLHGgoHQTgRpTn/8zIWWldKJfDnh5x5dILatxIitmH7FQzDY2dSZItE64v1+KAzsMUx+QeCdA51Rm+a0BeHVdU0DzEInGMh8B1uxGGQJNdK5yIpz+HdXuMlTw6KReXBRD4VlLgB99wPXyt387F74NFCGK2o5L1B7ZHM+NOuwWFqvlX5XTgrtqXTxvQScpCsnXUEURDlwWv7vNs3OcZgEZMhIcLkDmwctUwY=Three Stages of Innovation Acceptance

neighborhood effect Microscale diffusion in which acceptance of an innovation is most rapid in small clusters around an initial adopter.

Three Stages of Innovation Acceptance Acceptance of innovations at any given point in space passes through three distinct stages. In the first stage, acceptance takes place at a steady yet slow rate, perhaps because the innovation has not yet caught on, the benefits have not been adequately demonstrated, or a product is not readily available. During the second stage, rapid growth in acceptance occurs, and the trait spreads widely, as with a fashion style or dance fad. Often diffusion on a microscale exhibits what is called the neighborhood effect, which means simply that acceptance is usually most rapid in small clusters around an initial adopter. Due to increasing Internet use, the neighborhood effect is now also being observed in cyberspace. Online neighborhoods function, in many ways, like those in physical space. In other words, people who participate in certain online groups or sites may also demonstrate a neighborhood effect wherein new ideas and cultural innovations are accepted first by a person administering a site, writing a blog, or acting in some other prominent role. From that point, the new ideas or practices are accepted by other people in these online communities. During the third stage of innovation, acceptance, growth shows a slower rate than in the second, perhaps because the fad is passing or because an area (physical or virtual) is already saturated with the innovation.

Although all places and communities hypothetically have equal potential to adopt a new idea or practice, diffusion typically produces a core-periphery spatial arrangement, the same pattern observed earlier in our discussion of regions (see Figure 1.4). Hägerstrand offered an explanation of how diffusion produces such a regional configuration. The distribution of innovations can be random, but the overlap of new ideas and traits as they diffuse through space and time is greatest toward the center of the region and least at the peripheries. As a result of this overlap, more innovations are adopted in the center, or core, of the region.

migration The large-scale movement of people between different regions of the world.

transnationalism A phenomenon in which immigrants maintain social and/or economic ties to their place of origin. Often, these relationships include visits “home” and the circular exchange of money and goods.

In addition to the almost instant communication of ideas through the Internet and other digital media, we see many other examples of diffusion in today’s world. These include the rapid movement of goods from the place of production to the place of consumption and the seemingly nonstop movement of money around the globe through digital financial networks. These types of movements through space do not necessarily follow the pattern of core-periphery but instead create new and different types of patterns that are not yet fully studied or defined. Other types of diffusion, such as large-scale movements of people between different regions, can be best thought of as migration from one region or country to another through particular routes. In today’s globalizing world, with better and faster communication and transportation technologies, many migrants more easily maintain ties to their homelands even after they have migrated, and some may move back and forth between their home countries and those to which they have migrated. These movements and maintenance of ties lead to a phenomenon known as transnationalism.

A Special Case of Diffusion: Globalization

globalization The binding together of all the lands and peoples of the world into an integrated system driven by capitalistic free markets, in which cultural diffusion is rapid, independent states are weakened, and cultural homogenization is encouraged.

A Special Case of Diffusion: Globalization How and why are different cultures, economies, and societies linked around the world? Given all these new linkages, why are there so many differences between different groups of people in the world? The modern technological age, in which improved worldwide transportation and communications allow the instantaneous diffusion of ideas and innovations, has accelerated the phenomenon called globalization. This term refers to a world increasingly linked, in which international borders are diminished in importance and a worldwide marketplace is created. This interconnected world has been created from a set of factors: faster, cheaper, and more reliable transportation; the almost instantaneous communication that the Internet, cellular phones, and other media have allowed; and the creation of digital sources of information and media.

Thus, globalization in this sense is a rather recent phenomenon, dating from the late twentieth century. Yet we know that long before modern times, different countries and different parts of the world were linked. For example, in early medieval times overland trade routes connected China with other parts of Asia; the British East India Company maintained maritime trading routes between England and large portions of South Asia as early as the seventeenth century; and religious and political wars in Europe and the Middle East brought different peoples into direct contact with one another. Some geographers refer to such moments as early global encounters and suggest they set the background for contemporary globalization.

14

uneven development The tendency for industry to develop in a core-periphery pattern, enriching the industrialized countries of the core and impoverishing the less-industrialized periphery. The term is also used to describe urban patterns in which suburban areas are enriched while the inner city is impoverished.

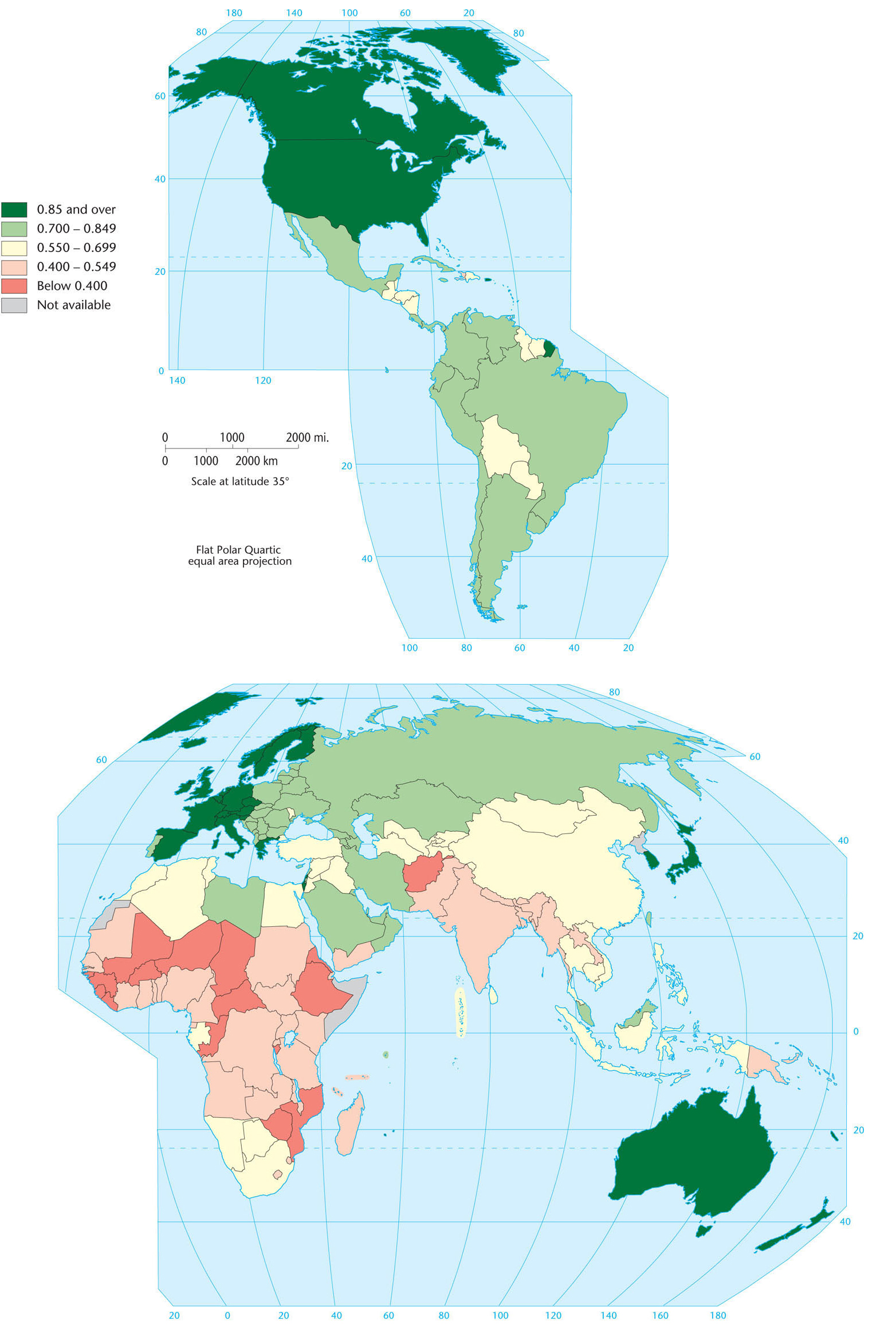

The increasingly linked economic, political, and cultural networks around the world might lead many to believe that different groups of people around the globe are becoming more and more alike. In some ways this is true, but actually these new global encounters have enabled an increasing recognition of the differences between groups of people, and some of those differences have been caused by globalization itself. Some groups of people have access to advanced technologies, more thorough health care, and education, whereas others do not. If we mapped certain indicators of human well-being on a global scale, such as life expectancy, literacy, and standard of living, we would find quite an uneven distribution. Figure 1.12 shows us that different cultures around the world have different access to these types of resources. These differences are what geographers mean when they refer to stages of development. In Figure 1.12, you can see that some regions of the world have a fairly high Human Development Index (HDI) and some have a relatively low HDI. Scholars often refer to these two types of regions as developed (relatively high HDI) and developing (relatively low HDI). This inequitable distribution of resources is referred to as uneven development. We will discuss development in much more detail in Chapters 3 and 9.

Human Development Index

Thinking Geographically

Question

0prHp0hBU+0zB/ni15fHm8AZiBY26oMKIAcc6RuI3yRledTaYi8DHrO71tn0y82HKuQ9Ofi+sZoLf4lWCXvDqhAWuys7yZiYHXVmJwnMHtfDRK3mztrYMi5qd4c=15

Culture, of course, is a key variable in global interactions and interconnections. In fact, as we have suggested, globalization is occurring through cultural media such as film, television, and the Internet (and particularly through social networking sites like Facebook and Twitter). These media provide channels that allow people to exchange information regarding trends in pop culture, product information, and changing lifestyles. In the case of the Internet, this exchange is virtually instantaneous. As a result, people’s choices to follow trends or to adopt technology and products from other cultures are more easily and quickly influenced by global changes than ever before. Figure 1.13 illustrates a diverse blend of global cultural influences on the once traditional cultural landscape of Ghana in West Africa. If we consider culture as a way of life, then globalization is a key shaper of culture and in turn is shaped by it. Some geographers have suggested that globalizing processes and an increase in personal mobility will work to homogenize different peoples, breaking down culture regions and eventually producing a single global culture. Other geographers see a different picture in which new forms of media and communication allow local cultures to maintain their distinct identities, reinforcing the diversity of cultures around the world. Throughout Fundamentals of The Human Mosaic, we will return to these issues, considering the complex role of culture and cultures in an increasingly global world.

Thinking Geographically

Question

TkClqzBz7OFKLjrz84cYQOVmc/XRaQRqIy64aXdEBV8vLRB0aJ4jtrBsljQRKn/Hy/YpGc5tq2RHC/oYkglcAAJqqGM6+jh15WNt8N3b69tj1/OZfMqvCJymAZ+oxL3IaUIAaNwPpONIeMo8rdNTqmFQmH2F8Ff6KWQxK4WkXzyipr7LlfsicYpp6Q4kvI9xnkpbNWUjKPoJQQPM48LocQ==16