Folk and Popular Cultural Landscapes

Folk and Popular Cultural Landscapes

Do folk and popular cultures look different? Do different cultures have distinctive cultural landscapes? The theme of cultural landscape reveals the important differences within and between cultures.

Folk Architecture

Folk Architecture

folk architecture Structures built by members of a folk society or culture in a traditional manner and style, without the assistance of professional architects or blueprints, using locally available raw materials.

Every folk culture produces a highly distinctive landscape. One of the most visible aspects of these landscapes is folk architecture. These traditional buildings illustrate the theme of cultural landscape in folk geography.

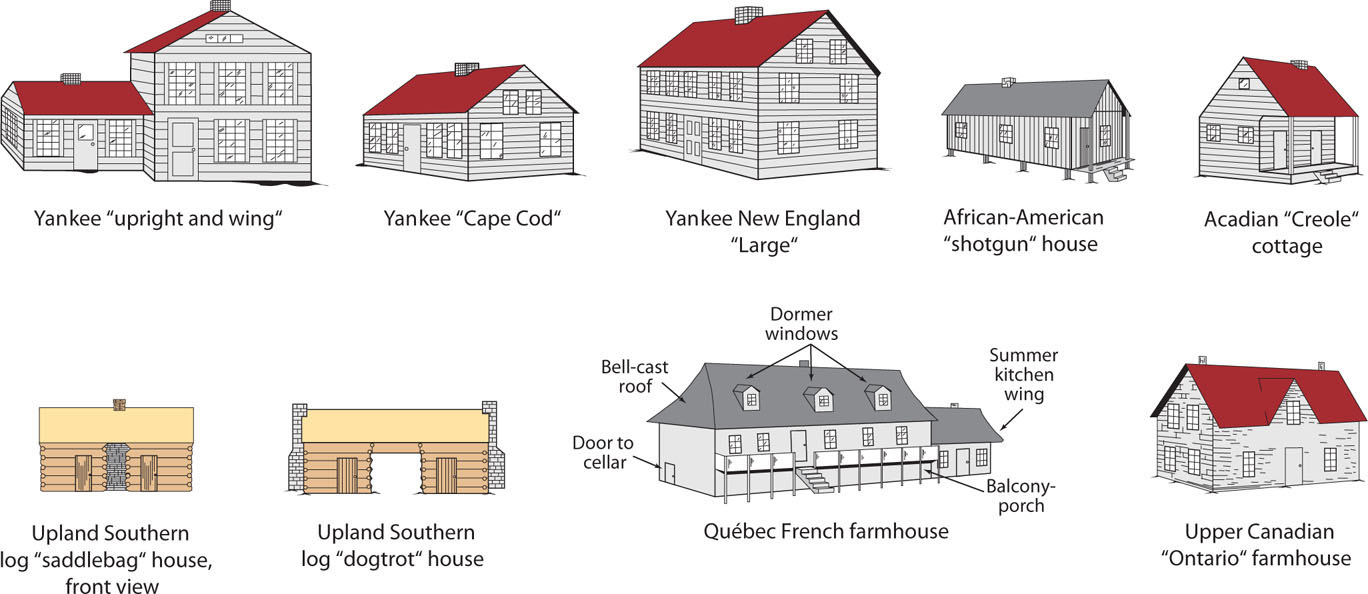

Folk architecture springs not from the drafting tables of professional architects but from the collective memory of groups of traditional people (Figure 2.22). These buildings—whether dwellings, barns, churches, mills, or inns—are based not on blueprints but on mental images that change little from one generation to the next. Folk architecture is marked not by refined artistic genius or spectacular revolutionary design but rather by traditional, conservative, and functional structures. Material composition, floor plan, and layout are important ingredients of folk architecture, but numerous other characteristics help classify farmsteads and dwellings. The form or shape of the roof, the placement of the chimney, and even such details as the number and location of doors and windows can be important classifying criteria. E. Estyn Evans, a noted expert on Irish folk geography, considered roof form and chimney placement, among other traits, in devising an informal classification of Irish houses.

Thinking Geographically

Question

qUEXbsE7ooMcnIfnPnByo+MYEQffsTXCfqx3fEFny5UsbOuRImRpiGJXe2i4EN7NvNOj8mGcaUhCJIbAPr2cX9qeEJ+AWLsXJdCCcsfNoJPvdp7VRcW5VFJjyTqH0zi7jhIAi7Vf6vYbvI6CxJmoO9CIrpHcl1hIYOoK836bfl3Z4l5XvbiCHzRSHnk38rEuwDgUGd9NM/I5bD1ILXjiNpsqelm9UyZxThe house, or dwelling, is the most basic structure that people erect, regardless of culture. For most people in nearly all folk cultures, a house is the single most important thing they ever build. Folk cultures as a rule are rural and agricultural. For these reasons, it seems appropriate to focus on the folk house.

49

Folk Housing in North America

Folk Housing in North America

In the United States and Canada, folk architecture today is a relict form preserved in the cultural landscape. That is, it has survived from an earlier period or in a primitive form. For the most part, popular culture, with its mass-produced, commercially built houses, has so overwhelmed the folk traditions that few folk houses are built today, yet many survive in the refuge regions of American and Canadian folk culture (see (Figures 2.1, 2.22).

Yankee folk houses are of wooden frame construction, and shingle siding often covers the exterior walls. They are built with a variety of floor plans, including the Yankee New England “large” house, a huge two-and-a-half-story house built around a central chimney and two rooms deep. As the Yankee folk migrated westward, they developed the upright-and-wing dwelling. These particular Yankee houses are often massive, in part because the cold winters of the region forced most work to be done indoors. By contrast, Upland Southern folk houses are smaller and built of notched logs. Many houses in this folk tradition consist of two log rooms, with either a double fireplace between, forming the saddlebag house, or a roofed breezeway separating the two rooms, a plan known as the dogtrot house (Figure 2.23). An example of an African-American folk dwelling is the shotgun house, a narrow structure only one room in width but two, three, or even four rooms in depth. Acadiana, a French-derived folk region in Louisiana, is characterized by the half-timbered Creole cottage, which has a central chimney and built-in porch. Scores of other folk house types survive in the American landscape, although most such dwellings now stand abandoned and derelict.

Thinking Geographically

Question

7h05chboS54WQx4JKsdz01NmPJAHjhKH0dJ9kEvi2DU+OX771x5gOK8vevoVEXSh6DXhl5ZqEr8RV7yR05w7h/KfimPbiNhpDsSqu4cqVJehLqlRWO47OH2MvRT7Pu7JReflecting on Geography

Question

eJoGbrzuQz4Z2Pdgm3D1LdgvDL0QVzNWnGpYYUgpBBZlxq47phTBxcYNUihFzE9vPXwSqxgusd/imvwl5PttANSF+e94VGcco7P2bJX0rFw7bC8YnCEg/CMu8EpnAsCM3716iKygR48mTZrGzmsnpzadzcGcwsT8ZlO30j/W3oasJzLSKFLu8SKuejd+FfjcGscpa72UERON9r4vCVmjG2hQcKQE36Cq8j+vJW6OW7I7INqcCanada also offers a variety of traditional folk houses (see Figure 2.22). In French-speaking Québec, one of the common types consists of a main story atop a cellar, with attic rooms beneath a curved, bell-shaped (or bell-cast) roof. A balcony-porch with railing extends across the front, sheltered by the overhanging eaves. Attached to one side of this type of French-Canadian folk house is a summer kitchen that is sealed off during the long, cold winter. Many of the folk houses of Québec are built of stone. To the west, in the Upper Canadian folk region, one type of folk house occurs so frequently that it is known as the Ontario farmhouse. One and a half stories high, the Ontario farmhouse is usually built of brick and has a distinctive gabled front dormer window.

Examine Figure 2.24 and test your ability to identify each type of house in the figure.

Thinking Geographically

Question

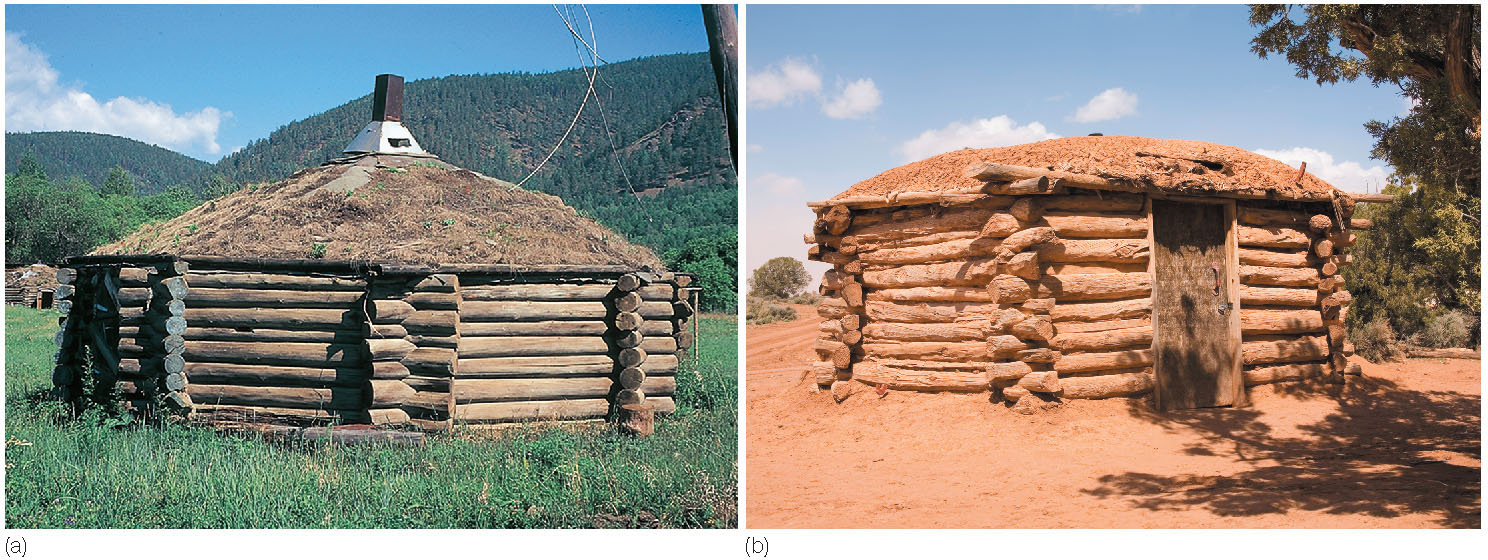

E9zgYS3ZggwwCalJjID0o2z8maYBuWpKWuRvWLpywoEGSNtbhYtTtLcB2fnsKX/wCT8mT7wu4SkGwSSJyiJV5h6GDHEoGiBu8QAj3CCAveLjz8vpwlTwt4tKuI+hUHBtei4xSWqD2r350RwfdwwZM3bUvT4pLoj9hxdw5HxV4K++o12+UjvlaIlOkGN/TMOzHBQ3LoN5+oHqVubnDYtcwAUPHpdfsxCALw7mBp7JDXfIOpBWNRAMM3qKIWpa60Hjqfv5X1MplYMZbkF55cKlCizFxwTLWE+kvRS/UH8+QE9G1pggr9GOkZNZ7KQYOBT/D238Xi6+O4azVAB8oy1UNg==The interpretation of folk architecture is by no means a simple process. Folk geographers often work for years trying to “read” such structures, seeking clues to diffusion and traditional adaptive strategies. The old problem of independent invention versus diffusion is raised repeatedly in the folk landscape, as Figure 2.25 illustrates. Precisely because interpretation is often difficult, however, geographers find these old structures challenging and well worth studying. Folk cultures rarely leave behind much in the way of written records, making their landscape artifacts all the more important in seeking explanations.

Thinking Geographically

Question

roINWm21sbrzbleKJ/GubiQbAxoCP2wuDuURNkYZqP/KZlLb+d+TAvVbEMocEjqKPJ0wpIwO/WWxrRLkJ41+yhM86+WwhzBsvTdJXjSSK4xq1OlgBfrgZEC+910gdrJcWrd0yjINsKYzAcgfkn7UNXHT4qmdlMa9Bj42xlWXT9KY7A8r50

Folk Housing in Sub-Saharan Africa

Folk Housing in Sub-Saharan Africa

Throughout East Africa and southern Africa, rural family homesteads take a common form. Most consist of a compound of buildings called a kraal, a term related to the English word corral and used across the region. The compound typically includes a main house (or houses in polygamous cultures), a detached building in the rear for cooking, and smaller buildings or enclosures for livestock.

All construction is done with local materials. Small, flexible sticks are woven in between poles that have been driven into the ground to serve as the frame. Then a mixture of clay and animal dung is plastered against the woven sticks, layer by layer, until it is entirely covered. Dried tall grasses are tied together in bundles to form the roof. In a recent innovation, rural people who can afford the expense have replaced the grass with corrugated iron sheets. In some societies the dwellings are round, in others square or rectangular. You can often tell when you have entered a different culture region by the change in house types.

One of the most distinctive house types is found in the Ndebele culture region of southern Africa, which stretches from South Africa north into southern Zimbabwe. In the rural parts of the Ndebele region, people are farmers and livestock keepers and live in traditional kraals. What makes these houses distinctive is the Ndebele custom of painting brightly colored designs on the exterior house walls and sometimes on the walls and gates surrounding the kraal (Figure 2.26). The precise origins of this custom are unclear, but it seems to date to the mid-nineteenth century. Some suggest that it was an assertion of cultural identity in response to their displacement and domination at the hands of white settlers. Others point to a religious or sacred role.

Thinking Geographically

Question

cGdJmcfnDsrpTpBHa+wfyuJbst8IxcTxyPIJFoVpeIqfWD53vKD0ZJyNhvvG7R5Lzk5453C+T0AlRz6wHbRLXKlokEY4YVZr8eEuO8LLdxAo4P5DFZHPdolChosq/GZxjkcHltkf65lppU3PFL5Ia46CefomQYufGj89Qt6aCWtfu1n4Mb3C1w==What is clear is that the custom has always been the purview of women, a skill and practice passed down from mother to daughter. Many of the symbols and patterns are associated with particular families or clans. Initially, women used natural pigments from clay, charcoal, and local plants, which restricted their palette to earth tones of brown, red, and black. Today many women use commercial paints—expensive but longer lasting—to apply a range of bright colors, limited only by the imagination. Another new development is in the types of designs and symbols used. People are incorporating modern machines such as automobiles, televisions, and airplanes into their designs. In many cases, traditional paints and symbols are blended with the modern to produce a synthetic design of old and new. Ndebele house painting is developing and evolving in new directions, all the while continuing to signal a persistent cultural identity to all who pass through the region.

51

Landscapes of Popular Culture

Landscapes of Popular Culture

Popular culture permeates the landscape of countries such as the United States, Canada, and Australia, including everything from mass-produced suburban houses to golf courses and neon-lit strips. So overwhelming is the presence of popular culture in most American settlement landscapes that an observer must often search diligently to find visual fragments of the older folk cultures. The popular landscape is in continual flux, for change is a hallmark of popular culture.

Few aspects of the popular landscape are more visually striking than the ubiquitous commercial malls and strips on urban arterial streets, which geographer Robert Sack calls landscapes of consumption (see Figure 2.6). In an Illinois college town, two other cultural geographers, John Jakle and Richard Mattson, made a study of the evolution of one such strip. During a 60-year span, the street under study changed from a single-family residential area to a commercial district. The researchers suggested a five-stage model of strip evolution, beginning with the single-family residential period, moving through stages of increasing commercialization, which drives owner-residents out, and culminating in stage 5, where the residential function of the street disappears and a totally commercial landscape prevails. Business properties expand so that off-street parking can be provided.

52

Public outcries over the ugliness of such strips are common. Even landscapes such as these are subject to interpretation, however, for the people who create them perceive them differently. For example, geographer Yi-Fu Tuan suggests that a commercial strip of stores, fast-food restaurants, filling stations, and used-car lots may appear as visual blight to an outsider, but the owners or operators of the businesses are very proud of them and of their role in the community. Hard work and high hopes color their perceptions of the popular landscape.

Perhaps no landscape of consumption is more reflective of popular culture than the indoor shopping mall, numerous examples of which now dot both urban and suburban landscapes. Of these, the largest is West Edmonton Mall in the Canadian province of Alberta (Figure 2.27). Enclosing some 5.3 million square feet (493,000 square meters) and opened in 1986, West Edmonton Mall employs 23,500 people in more than 800 stores and services, accounts for nearly one-fourth of the total retail space in greater Edmonton, earned 42 percent of the dollars spent in local shopping centers, and experienced 2800 crimes in its first nine months of operation. Beyond its sheer size, West Edmonton Mall also boasts a water park, a sea aquarium, an ice-skating rink, a miniature golf course, a roller coaster, 21 movie theaters, and a 360-room hotel. Its “streets” feature motifs from such distant places as New Orleans, represented by a Bourbon Street complete with fiberglass ladies of the evening. Jeffrey Hopkins, a geographer who studied this mall, refers to this as a “landscape of myth and elsewhereness,” a “simulated landscape” that reveals the “growing intrusion of spectacle, fantasy, and escapism into the urban landscape.”

Thinking Geographically

Question

GUQa257b1bf1OrE07Lk69+WC6e/Ef2p8y+234tgQmwkT9/49t7wT4F0GVPLZVpl/pRhF0Z2BK+x545K5idJAGC4btoEy4LTQvDoKzWOMjCiQBg/E2mzlMwA+ngo4huFsBPbNJ6/a9JMtLzKFjx6rig==Leisure Landscapes

Leisure Landscapes

leisure landscape A landscape that is planned and designed primarily for entertainment purposes, such as ski and beach resorts.

amenity landscape Landscape that is prized for its natural and cultural aesthetic qualities by the tourism and real estate industries and their customers.

Another common feature of popular culture is what geographer Karl Raitz labeled leisure landscapes. Leisure landscapes are designed to entertain people on weekends and vacations; often they are included as part of a larger tourist experience. Golf courses and theme parks such as Disney World are good examples of such landscapes. Amenity landscapes are a related landscape form. These are regions with attractive natural features such as forests, scenic mountains, or lakes and rivers that have become desirable locations for retirement or vacation homes. One such landscape is in the Minnesota North Woods lake country, where, in a sampling of home ownership, geographer Richard Hecock found that fully 40 percent of all dwellings were not permanent residences but instead weekend cottages or vacation homes. These are often purposefully made rustic or even humble in appearance.

The past, reflected in relict buildings, has also been incorporated into the leisure landscape. Most often, collections of old structures are relocated to form “historylands,” often enclosed by imposing chain-link fences and open only during certain seasons or hours. If the desired bit of visual history has perished, Americans and Canadians do not hesitate to rebuild it from scratch, undisturbed by the lack of authenticity—as, for example, at Jamestown, Virginia, or Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. Normally, the history parks are put in out-of-the-way places and sanitized to the extent that people no longer live in them. Role-playing actors sometimes prowl these parks, pretending to live in some past era, adding “elsewhenness” to “elsewhereness.”

53

Elitist Landscapes

Elitist Landscapes

A characteristic of popular culture is the development of social classes. A small elite group—consisting of persons of wealth, education, and expensive tastes—occupies the top economic position in popular cultures. The important geographical fact about such people is that because of their wealth, desire to be around similar people, and affluent lifestyle, they can and do create distinctive cultural landscapes, often over fairly large areas.

Daniel Gade, a cultural geographer, coined the term elitist space to describe such landscapes, using the French Riviera as an example. A photo illustrating the opulence of this elitist space can be found in chapter 1 (Figure 1.9). Like other elitist landscapes, the Riviera visually produces distinctive cultural divides between the wealthy and the less affluent. These social-class divisions are equally evident in many evolving cultural landscapes around the world. Figure 2.28 illustrates one contemporary elitist landscape in the oil- and tourism-rich United Arab Emirates (UAE). Due to the warm, sunny climate in this Middle Eastern state, as well as the availability of amenities like world-class golf courses and luxury shopping venues, the UAE has become a popular destination for celebrities and the ultra-wealthy. The grand scale and over-the-top opulence of the resorts, high-rise dwellings, and human-made private islands (all constructed to attract affluent people) have become part of a new elitist landscape. Other elitist landscapes are also taking shape in many of the world’s tropical regions in the form of private island ownership by celebrities such as Johnny Depp and Mel Gibson and business moguls like Virgin’s Richard Branson. These wealthy individuals participate in the creation of new elite spaces that are financially inaccessible to people in less affluent social classes. In this way, social divisions are made apparent and emphasized on the cultural landscape.

Thinking Geographically

Question

uTPa1CbCsaGaf+8IqGOxqhssRf0aEwwvJwJvlHu1ekMghyr/8vVwoiiCHZVLkqWitPOApiajJrUvbcei8uBMvHG0jNLvVSOe0MtBdFu8Uzw05xKJt4sPApU+FfcjZrpFvSN0WxW9E/WeoMu2teLsQ4RDsYZPseaKmoy/b3r2i8A=54

America, too, offers elitist landscapes. An excellent example is the gentleman farm, an agricultural unit operated for pleasure rather than profit (Figure 2.29). Typically, affluent city people own gentleman farms as an avocation, and such farms help to create or maintain a high social standing for those who own them. Some rural landscapes in America now contain many such gentleman farms; perhaps most notable among these places are the inner Bluegrass Basin of north-central Kentucky, the Virginia Piedmont west of Washington, D.C., eastern Long Island in New York, and parts of southeastern Pennsylvania. Gentleman farmers engage in such activities as breeding fine cattle, racing horses, or hunting foxes.

Thinking Geographically

Question

fbodDkpW/iGuIyqeuEKbj/8GInaHlBiyU0yZ4gpViVt8N8S2ECGOjoTGD9ZautC/FrRHAs4d4iav4DHpKQJYdsgPVD+sD4xgANGBsQcG8zbxxH1Gi2Ob7R5e/ltQCosvlksdlvNWNpDKUrFmbpjclR/xGX+vGGDXKXGQErK/A/s=Geographer Karl Raitz conducted a study of gentleman farms in the Kentucky Bluegrass Basin, where their concentration is so great that they constitute the dominant feature of the cultural landscape. The result revealed an idyllic scene, a rural landscape created more for appearance than for function. Raitz provided a list of visual indicators of Kentucky gentleman farms: wooden fences, either painted white or creosoted black; an elaborate entrance gate; a fine hand-painted sign giving the name of the farm and owner; a network of surfaced, well-maintained driveways and pasture roads; and a large, elegant house, visible in the distance from the public highway through a lawnlike parkland dotted with clumps of trees and perhaps a pond or two. So attractive are these estates to the eye that tourists travel the rural lands to view them, convinced they are seeing the “real” rural America, or at least rural America as it ought to be.

Reflecting on Geography

Question

dUe84d2WgBCdB6mklM5HRAydUcdyiTjQF5KoTKOUMRyMhhctrDsC4Z3y11ONXuKGr2dsKfq8rahluzHgdkvc7JYr/pg3jqatbCPVPLqnK3LUjQgwzYMMt9xyhLVdKC5VThe American Popular Landscape: The Cult of Bigness?

The American Popular Landscape: The Cult of Bigness?

Geographer David Lowenthal has attempted to analyze the cumulative visible impact of popular culture on the American countryside. Lowenthal identified the main characteristics of popular landscape in the United States, including the “cult of bigness”; the tolerance of present ugliness to achieve a supposedly glorious future; an emphasis on individual features at the expense of aggregates, producing a “casual chaos”; and the preeminence of function over form.

The American fondness for massive structures is reflected in edifices such as the Empire State Building, the Pentagon, the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge, and Salt Lake City’s Mormon Temple. Americans have dotted their cultural landscape with the world’s largest of this or that, perhaps in an effort to match the grand scale of the physical environment, which includes such landmarks as the Grand Canyon, the towering redwoods of California, and the Rocky Mountains.

Americans, argues Lowenthal, tend to regard their cultural landscape as unfinished. As a result, they are “predisposed to accept present structures that are makeshift, flimsy, and transient,” resembling “throwaway stage sets.” Similarly, the hardships of pioneer life perhaps preconditioned Americans to value function more highly than beauty and form. In summary, American popular culture seems to have produced a built landscape that stresses bigness, utilitarianism, and transience. Sometimes these are opposing trends, as in the case of many of the massive structures previously cited, which are clearly built to last. Sometimes the trends mesh, as in the explosion of “big box” retail chains. These giant retail buildings are no more than oversized metal sheds that one can easily imagine being razed overnight to be replaced by the next big thing.