The Settlement Landscape

The Settlement Landscape

What are the many ways that demographic factors are expressed in the cultural landscape? Population geographies are visible in the landscapes around us. The varied densities of human settlements and the shapes these take in different places provide clues to the intertwined cultural and demographic strategies enacted in response to diverse local factors. These clues are evident wherever people have settled, be it urban, suburban, or rural. Less visible—but no less important—factors are also at work on and throughout the cultural landscape. Politics, economics, and gender relations provide three examples of the larger power relations that can shape the cultural-demographic landscape. We open this final part of the chapter by examining rural settlement patterns, which illustrate how demographics, culture, and the landscape work together to create a variety of settlements.

84

Rural Settlement Patterns

Rural Settlement Patterns

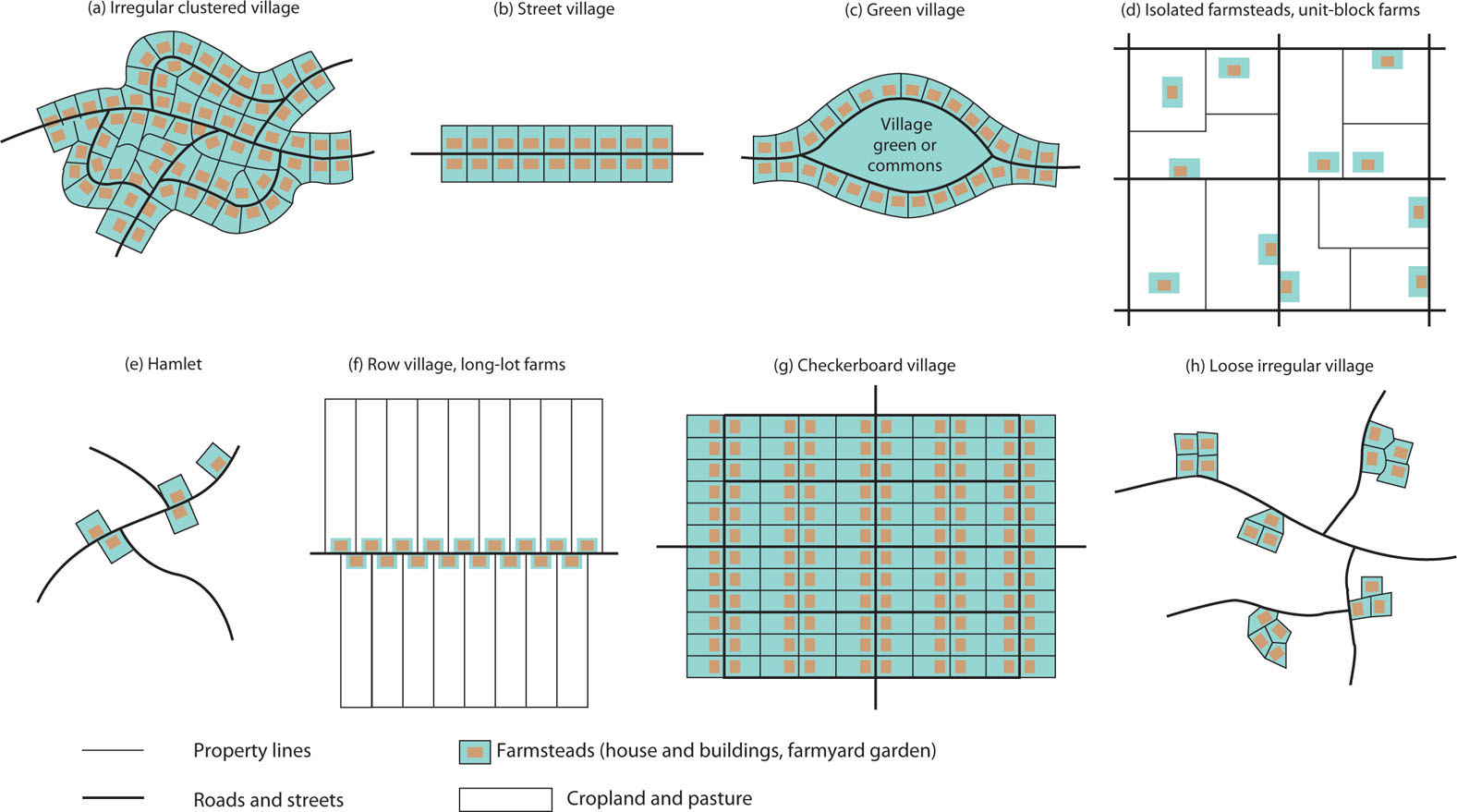

Differing densities and arrangements of population are revealed, at the largest scale, by maps showing the distribution of dwellings. These differences in the cultural landscape can be illustrated by using the example of rural settlement types. Farm people differ from one culture to another, one place to another, in how they situate their dwellings, producing greatly varied rural cultural landscapes. They range from tightly clustered villages on the one extreme to fully dispersed farmsteads on the other, as shown in Figure 3.22.

Thinking Geographically

Question

EsE0HFmK0sDIwHR3N0rk1rJ+oZ/8S+ceyoYPgiUlQp3Q2JbwoRIDj1zW8oGF8hf70inUAbM13S4jTNT5TH/7L2AtSdh/Lq5R4g7Oo4g79o2OBAODHPBLSO+TcQU2ecgxPl8XhHTy96PR3rFKUpcBZsnYv7sNoFn/05BDjcEtAseEIqwLPYq17ccCQzLyUvbBlhSws0t9WM7iKHZHlXlDEQ==Farm Villages

farm village Clustered, tightly bunched rural settlement inhabited by people who are engaged in farming.

farmstead The center of farm operations, containing the house, barn, sheds, livestock pens, and garden.

Farm Villages In many parts of the world, farming people group themselves together in clustered settlements called farm villages. These tightly bunched settlements vary in size from a few dozen inhabitants to several thousand. Contained in the village farmstead are the house, barn, sheds, pens, and garden. The fields, pastures, and meadows lie out in the country beyond the limits of the village, and farmers must journey out from the village each day to work the land.

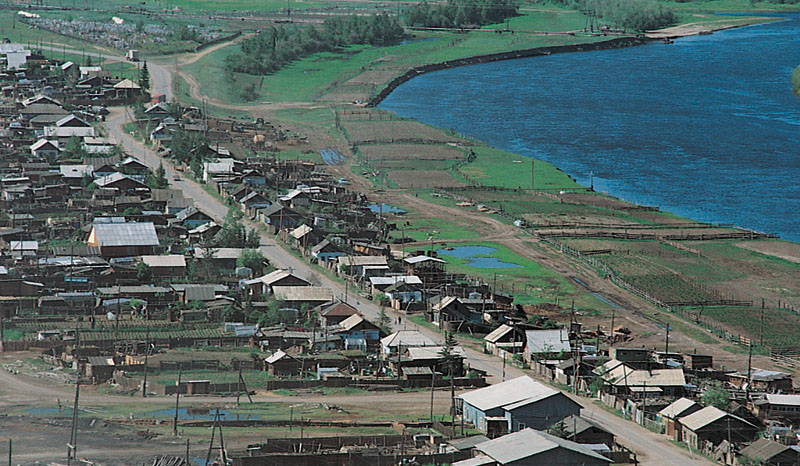

Farm villages are the most common form of agricultural settlement in much of Europe, in many parts of Latin America, in the densely settled farming regions of Asia (including much of India, China, and Japan), and among the sedentary farming peoples of Africa and the Middle East. These compact villages come in many forms. Most are irregular clusterings—a maze of winding, narrow streets and a jumble of farmsteads (Figures 3.22a and 3.23). Such irregular clustered farm villages developed organically over centuries, without any orderly plan to direct their growth. Other types of farm villages are very regular in their layout, revealing the imprint of planned design. The street village, the simplest of these planned types, consists of farmsteads grouped along both sides of a single central street, producing an elongated settlement (Figures 3.22b and 3.24). Street villages are particularly common in eastern Europe and much of Russia. Another type, the green village, consists of farmsteads grouped around a central open place, or green, which forms a commons (see Figure 3.23). Green villages occur throughout most of the plains areas of northern and northwestern Europe, and English immigrants laid out some such settlements in colonial New England. Also regular in layout is the checkerboard village, based on a gridiron pattern of streets meeting at right angles (see Figure 3.22g). Mormon farm villages in Utah are of this type, and checkerboard villages also dominate most of rural Latin America and northeastern China.

Thinking Geographically

Question

auGDsm0J5GLIBD8uXWkYOqEGQ1QHKViz6ComYJ8VEgyTygyzhu/UhRW0W0ifiRaM71z/PethotCHa517t26bsn5y+ycnpa5r

Thinking Geographically

Question

auGDsm0J5GLIBD8uXWkYOqEGQ1QHKViz6ComYJ8VEgyTygyzhu/UhRW0W0ifiRaM71z/PethotCHa517t26bsn5y+ycnpa5r85

Why do so many farm people settle together in villages? Historically, the countryside was unsafe, threatened by roving bands of outlaws and raiders. Farmers could better defend themselves against such dangers by grouping together in villages. In many parts of the world, the populations of villages have grown larger during periods of insecurity and shrunk again when peace returned. Many farm villages occupy the most easily defended sites in their vicinity, what geographers call strong-point settlements.

86

In addition to defense, the quality of the environment helps determine whether people settle in villages. In deserts and in limestone areas where the ground absorbs moisture quickly, farmsteads are built around the few sources of water. Such wet-point villages cluster around oases or deep wells. Conversely, a superabundance of water—in marshes, swamps, and areas subject to floods—often prompts people to settle in villages on available dry points of higher elevation.

Various communal ties strongly bind villagers together. Farmers linked to one another by blood relationships, religious customs, communal landownership, or other similar bonds usually form clustered villages. Mormon farm villages in the United States provide an excellent example of the clustering force of religion. Communal or state ownership of the land—as in China and parts of Israel—encourages the formation of farm villages.

Isolated Farmsteads

Isolated Farmsteads In many other parts of the world, the rural population lives on dispersed, isolated farmsteads, often some distance from their nearest neighbors (see Figure 3.22d). These dispersed rural settlements grew up mainly in Anglo-America, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa—that is, in the lands colonized by emigrating Europeans. But even in areas dominated by village settlements—such as Japan, Europe, and parts of India—some isolated farmsteads appear (Figure 3.25).

Thinking Geographically

Question

nyIswa3z1LNS0GIaNxw9kApBOuhGyn02qP3J9ZzJopCIVL5slroM0hT+x7Jm6M/y1ZHn5J7Pm5lnn+Lv197sQWHjwnI1MDfqbJADy5B/PUl+zKMZ2MB6CeIOly/749Bc8ZuapetE8VlhUpPN18N0cZo9SXr4IiRVImb4piARh5HSPjoVMSmwV1wg8fY=The conditions encouraging dispersed settlement are precisely the opposite of those favoring village development. These include peace and security in the countryside, eliminating the need for defense; colonization by individual pioneer families rather than by socially cohesive groups; private agricultural enterprise, as opposed to some form of communalism; and well-drained land where water is readily available. Most dispersed farmsteads originated rather recently, dating primarily from the colonization of new farmland in the past two or three centuries.

Reflecting on Geography

Question

VGM22v7vwtM16tI8Ihx09r41NGN7mdOkwUxRod/3+wTcznXkyzf9Ab/k40zyFa5QPtFDnqHpXbRVyvAwGs5gQK/ItgKXu2BMUkdWikTa7bXfBoxr/wRWOYQdNkNFALOGQlv2Iw0j7si1Mf5oIrH9qWac2Y5OD+H9Historical Factors Shaping the Cultural-Demographic Landscape

Historical Factors Shaping the Cultural-Demographic Landscape

The rural settlement forms described previously give geographers a chance to read the cultural landscape. In doing so, we must always be cautious, looking for the subtle as well as the overt, and not form conclusions too quickly.

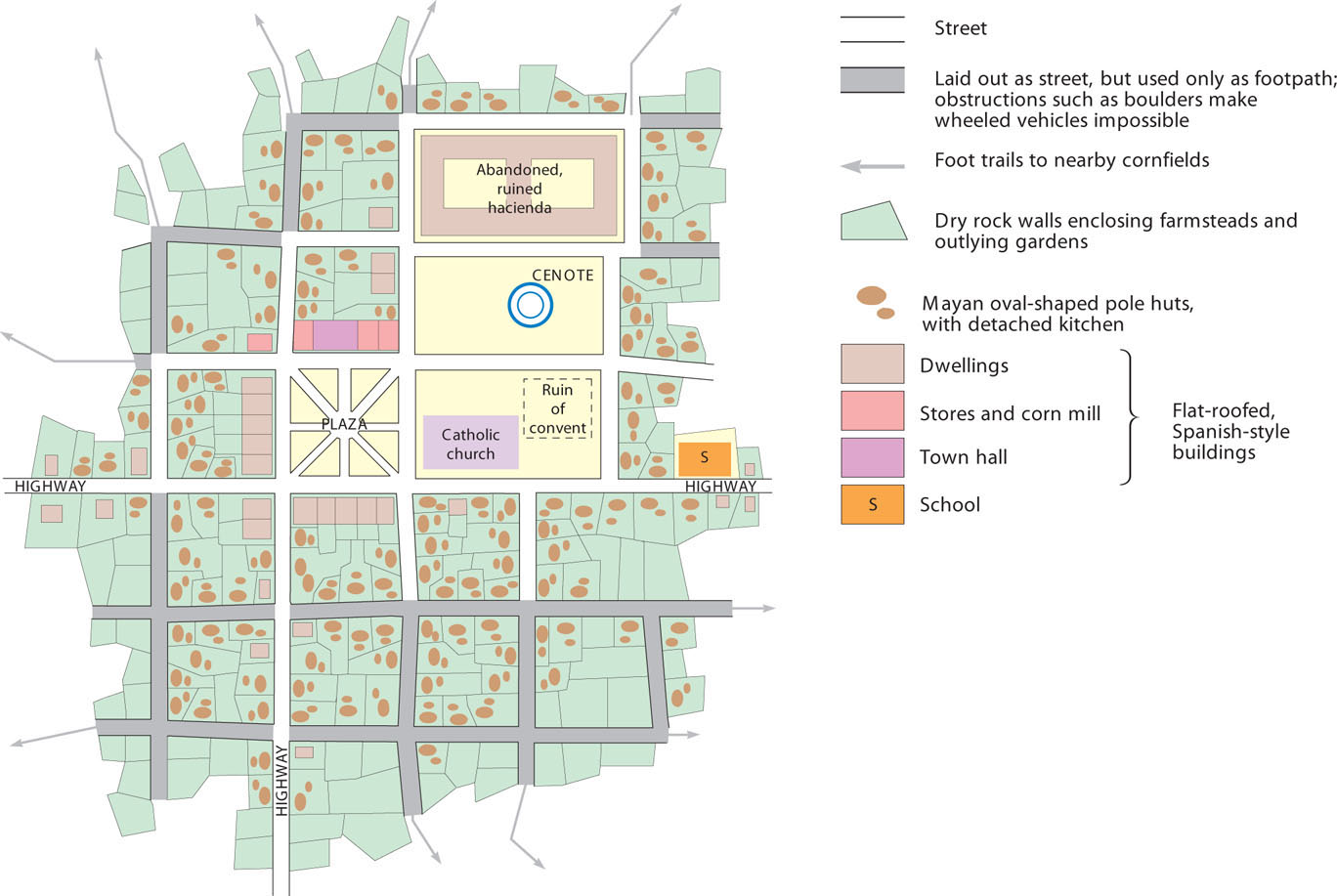

For example, the Maya of the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico reside in checkerboard villages, a rural settlement landscape that is both suggestive and potentially misleading (Figure 3.26). Before the Spanish conquest in the late 1400s, the Maya lived in wet-point villages of the irregular clustered type, situated alongside cenotes—natural sinkholes that provided water in a land with no surface streams. The Spaniards destroyed these settlements, replacing them with checkerboard villages. Wide, straight streets accommodated the wheeled vehicles of the European conquerors.

Thinking Geographically

Question

+jTdFiHcBfSHO0zPHidoXNNIrgoUzZRX5fxLbXD24HIQ0zxFcnoTSHYT+ciUlfISSlK//nbdwwzv0FbLSYx6Ionz+QLDQ8ha7GoBILBehHdxF1K5UzvY+x/1OWLBhuW5q+9qmZinPkGRQszJSuperficially, the checkerboard landscape suggests the cultural victory of the Spaniards. A closer look, however, shows that, in fact, Mayan culture prevailed. Even today, many Maya make little use of wheeled vehicles in village life, and many of the Spaniards’ streets merely make way for Mayan footpaths that wind among boulders and outcroppings of bedrock. Irregularities in the checkerboard, coupled with a casual distribution of dwellings, suggest Mayan resistance to the new geometry. Spanish-influenced architecture—flat-roofed houses of stone, the town hall, a church, and a hacienda mansion—remain largely confined to the area near the central plaza. The Catholic church stands on the very place where an ancient Mayan temple was. A block away, the traditional Mayan pole huts with thatched, hipped roofs prevail, echoed by cookhouses of the same design. Indian influence increases markedly with distance from the plaza.

87

The dooryard gardens surrounding each hut are full of traditional native plants—such as papayas, bananas, chili peppers, nuts, yucca, and maize—with only a few citrus trees to reveal Spanish influence. In the same yards, each carefully ringed with dry rock walls, as in pre-Columbian times, pigs descended from those introduced by the conquerors share the ground with the traditional turkeys of the Maya and apiaries for indigenous stingless bees. Occasionally, the Mayan language is heard, although Spanish prevails. So does Catholicism, but the absence of huts around the once-sacred cenote suggests a lingering pagan influence.

Gender and the Cultural-Demographic Landscape

Gender and the Cultural-Demographic Landscape

Gender often interacts with other factors to influence geodemographic patterns and migrations. For example, together gender, race, and nationality can create situations in which women from specific countries are viewed as desirable immigrants. In nineteenth-century America, Irish female immigrants were considered to be highly reliable employees and often found work as domestic servants.

For several decades now, women from the Philippines have migrated to Hong Kong to work as domestic servants, doing chores for and looking after the children of the families who hire them. Wages in Hong Kong are much higher than back home in the Philippines, prompting the migration. However, working conditions can be far from ideal, involving hard physical labor and long hours. Reports of abuse of Filipina servants by their employers are numerous. If a servant is fired and cannot quickly find another job, she will be deported. The stress of long separations from husbands and children back in the Philippines has led to the breakup of families.

Some of these women are coerced into Asia’s booming sex industry, as well. Geographer James Tyner has studied migration from the Philippines to Japan. Incredibly, 93 percent of this migration consists of female “entertainers.” In part, poverty in the Philippines provided the push factor in this movement. Tyner also points to more complex pull factors, such as the stereotypical view held by Japanese men in which Filipinas are seen as highly desirable, exotic sex objects but also culturally inferior and thus “willing victims” who gladly become prostitutes. Thus, the gendered landscape becomes an attraction for human mobility other than work-related migration: in this case, sex tourism.

88

Landscapes and Demographic Change

Landscapes and Demographic Change

depopulation A decrease in population that sometimes occurs as the result of sudden catastrophic events, such as natural disasters, disease epidemics, and warfare.

Population change in a place can occur rapidly or more slowly over time. Rapid depopulation can come about as the result of sudden catastrophic events, such as natural disasters, disease epidemics, and warfare. Or depopulation can take place at a slower pace. For example, places may lose population over time because of the gradual out-migration of people in search of opportunities elsewhere, as a cumulative result of declining fertility rates, or as a response to climate change.

Populations can also grow in more or less rapid fashions. A place might experience an abrupt influx of people who have been displaced from other areas. Population increases commonly occur more gradually, as the result of demographic improvements such as longer life spans or lower infant mortality rates, or the accumulation of steady streams of immigrants to attractive areas over time.

Depopulation in one area and population increase in another are often linked processes. For instance, you could easily envision a scenario in which the same natural disaster victims leaving one place become the refugees suddenly flooding into a neighboring area. As a longer-term example, you could equally well imagine how broad economic changes or technological innovations could lead to regional population shifts whereby some areas become depopulated and others gain population.

Regardless of the reasons, population changes must be accommodated, and these adaptations are invariably reflected in the cultural landscape.

Bogotá Rising

Bogotá Rising Dilapidated-looking landscapes can result from population decline, but they can also arise from rapid population influx. Many of the world’s shantytowns exemplify the sort of chaotic landscape that can result from rapid population increases. Los Altos de Cazucá, a neighborhood in the Colombian capital of Bogotá, is but one example. In this case, the population influx comes mostly from people arriving in the capital after being displaced by armed conflict in the countryside.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that by 2009 there were 26 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) due to armed conflict worldwide. Colombia is one of the globe’s hotspots for IDPs, alongside Sudan. Colombia’s estimated 5 million IDPs have been uprooted largely as the result of ongoing civil warfare between the paramilitary group known as the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) and government forces bent on eradicating them. The UNHCR has identified this as the “worst humanitarian crisis in the Western Hemisphere.”

Colombia’s armed conflict has depopulated the rural areas where it occurs, forcing its victims into the cities. Terrorized, landless, and impoverished, the mainly indigenous and Afro-Colombian IDPs settle in the outskirts of cities like Colombia’s capital, Bogotá.

shantytown A deprived area on the outskirts of a town consisting of a large number of crude dwellings.

Los Altos de Cazucá is one of the settlements inhabited by Colombia’s internally displaced persons (Figure 3.27). Known as shantytowns, areas like Los Altos de Cazucá arise for various reasons, but they exist in all large cities throughout the developing world. Housing is constructed by the residents themselves, using found materials like cardboard, tin panels, and old tires. Some shantytowns are far from downtown areas where wealthy people reside and where jobs are, while others are literally pressed up against wealthier neighborhoods (Figure 3.28).

Thinking Geographically

Question

Z5J8562Bqtbm3v1Zb4FyOmSn+pcxhorYx1Ww7RsZqLTtQeEq0ePdXP3LMw2EvUkyoUQhHmRbvuqo7uii1gj0CzudYGaelay+dU5zJ/KwPL4F3IDQCInsz17FBydMk8YNfpDXO37kuzOzJEGADHD4qQ==

Thinking Geographically

Question

367IxD+0DlZnRsDUFhze39sMnCL3gdy66PhzNB3JZpoMRzQXF/1mls1xrTwcPS3/kTYowmD9W62FyVhomSD0rbbm2+Bmqa71o52UdynM3rE3yY8eT8qvpxAW/BVFonUB5gGDOG7gpJM=89

Most shantytowns arise spontaneously to address population influx to cities that lack the resources to plan systematically for rapid growth. But are shantytowns temporary, disappearing as their residents become incorporated into city life? Interestingly, shantytowns gradually become part of the urban fabric. Indeed, most of the spatial expansion of Latin American cities like Bogotá occurs precisely thanks to growth of the shantytowns surrounding them. Over time, the dwellings are constructed of more-permanent materials such as concrete blocks. Roads are paved and running water installed. Power and phone lines are extended. The once-temporary areas slowly become visually, economically, and culturally integrated into the permanent fabric of the city. New shantytowns to accommodate recent arrivals then arise beyond their borders.