Cultural-Linguistic Interaction

Cultural-Linguistic Interaction

Language is intertwined with all aspects of culture. The theme of cultural interaction permits us to probe some of these complex links between speech and other cultural phenomena. The complicated linguistic map cannot be understood without reference to the comparative social, demographic, political, and technological characteristics of the groups in question. At root, linguistic cultural interaction often reflects the dominance of one group over another, a dominance based in culture.

Religion and Language

Religion and Language

Cultural interaction creates situations in which language is linked to a particular religious faith or denomination, a linkage that greatly heightens cultural identity. Perhaps Arabic provides the best example of this cultural link. It spread from a core area on the Arabian Peninsula with the expansion of Islam. Had it not been for the evangelical success of the Muslims, Arabic would not have diffused so widely. The other Semitic languages also correspond to particular religious groups. Most Hebrew-speaking people are Jewish, and the Amharic speakers in Ethiopia tend to be Coptic, or Eastern, Christians. Indeed, we can attribute the preservation and recent revival of Hebrew to its active promotion by Jewish nationalists who believe that teaching and promoting Hebrew to diasporic Jews facilitates unity.

107

108

Certain languages have acquired a religious status. Latin survived mainly as the ceremonial language of the Roman Catholic Church and Vatican City. In non-Arabic Muslim lands, such as Iran, where people consider themselves Persians and speak Farsi, Arabic is still used in religious ceremonies. Great religious books can also shape languages by providing them with a standard form. Martin Luther’s translation of the Bible led to the standardization of the German language, and the Koran is the model for written Arabic. Because they act as common points of frequent cultural reference and interaction, great religious books can also aid in the survival of languages that would otherwise become extinct. The early appearance of a hymnal and the Bible in Welsh aided the survival of that Celtic tongue, and Christian missionaries in diverse countries have translated the Bible into local languages, helping to preserve them. In Fiji, the appearance of the Bible in one of the 15 local dialects elevated it to the dominant native language of the islands.

Technology, Language, and Empire

Technology, Language, and Empire

Technological innovations affecting language range from the basic practice of writing down spoken languages to the sophisticated information superhighway provided by the Internet. Technological innovations have in the past facilitated the spread and proliferation of multiple languages, but more recently they have encouraged the tendency of only a few languages—especially English—to dominate all others. Particular language groups achieve cultural dominance over neighboring groups in a variety of ways, often with profound results for the linguistic map of the world. Technological superiority is usually involved. Plant and animal domestication—the technology of the “agricultural revolution”—aided the early diffusion of the Indo-European language family.

An even more basic technology was the invention of writing, which appears to have developed as early as 5300 years ago in several hearth areas, including in Egypt, among the Sumerians in what is today Iraq, and in China. Writing helped civilizations develop and spread, giving written languages a major advantage over those that remained spoken only. Written languages can be published and distributed widely, and they carry with them the status of standard, official, and legal communication.

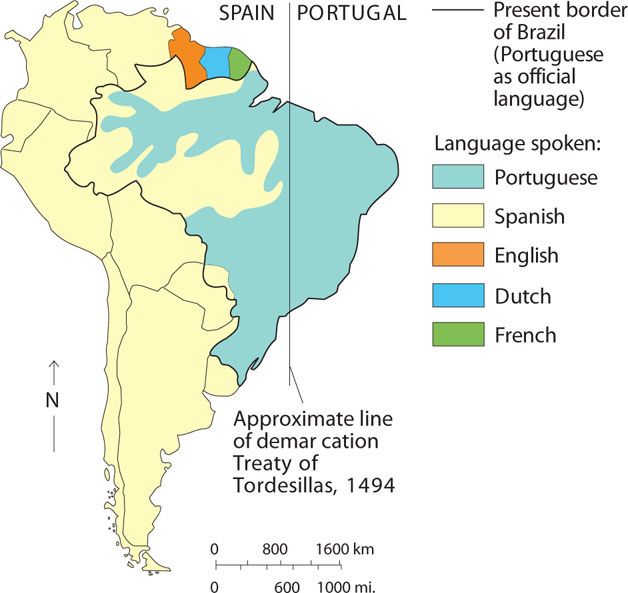

Written language facilitates record keeping, allowing governments and bureaucracies to develop. Thus, the languages of conquerors tend to spread with imperial expansion. The imperial expansion of Britain, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Portugal, Spain, and the United States across the globe altered the linguistic practices of millions of people (Figure 4.11). This empire building superimposed Indo-European tongues on the map of the tropics and subtropics. The areas most affected were Asia, Africa, and the Austronesian island world. A parallel case from the ancient world is China, also a formidable imperial power that spread its language to those it conquered. During the Tang dynasty (a.d. 618–907), Chinese control extended to Tibet, Mongolia, Manchuria (in contemporary northeastern China), and Korea. The 4000-year-old written Chinese language proved essential for the cohesion and maintenance of its far-flung empire. Although people throughout the empire spoke different dialects or even different languages, a common writing system lent a measure of mutual intelligibility at the level of the written word.

Thinking Geographically

Question

GSpQ6RfQEMqKOXydvrmpphdViichCghkoIz48xLPqaRbncsBaxf+sQ0wkjcmie9EBIXeiHSXBIC0E5w2qBM4t8NCY+knm9r2ad9yCPhJwGICnAGuUvAAB+M3MP4=Even though imperial nations have, for the most part, given up their colonial empires, the languages they transplanted overseas survive. As a result, English still has a foothold in much of Africa, South Asia, the Philippines, and the Pacific islands. French persists in former French and Belgian colonies, especially in northern, western, and central Africa; Madagascar; and Polynesia (Figure 4.12). In most of these areas, English and French function as the languages of the educated elite, often holding official status. They are also used as a lingua franca of government, commerce, and higher education, helping hold together states with multiple native languages.

Thinking Geographically

Question

YPvS4QHipuuqp8KN4fMAiVFy0LE3S3o8UxnFSuJ3hT29OCZdKCIxjPpfMwnnddu5kDoWblfKo/VyoEYoVA5kK+1QohLtn+NbruGiwbpD4Y/CHMQ6EfHM09baoH2aGaWZzTV9Wg==109

Transportation technology also profoundly affects the geography of languages. Ships, railroads, and highways all serve to spread the languages of the cultural groups that build them, sometimes spelling doom for the speech of less technologically advanced peoples whose lands are suddenly opened to outside contacts. The Trans-Siberian Railroad, built about a century ago, spread the Russian language eastward to the Pacific Ocean. The Alaska Highway, which runs through Canada, carried English into Native American refuges. The construction of highways in Brazil’s remote Amazonian interior threatens the native languages of that region.

Reflecting on Geography

Question

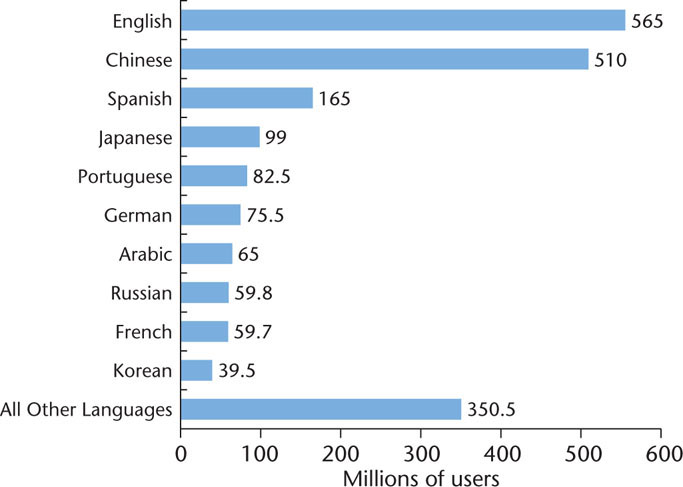

odiOBIz2035qwWYeLZLiQXAD0cDXQ5Fgu/Vl7Y24bDdQ9hWCMz/FYBmiqNwXrL+tWbShx0i4Efz2bIpH/ceYqLNbthBUCvACqqjNI0nMQ8SVqOlonp0n+IzD2xBO4KK6e2es/QFSNG1wKuh2+FuJFulxrcvl9ATnG2Pb2g6hw/6mXkIW9XWZ5inSMUs0eCBtzcUDN5blOKqbao6maIn/QHYOZjujWiLr02Oc4XmMcde0RVbInSB1zSZ72QOcpealRu2ADzMOeQUAn0YjHbk0bd+Z7QReugl4uaWbIm6UxdOflsl0NJGhCovybABndQj8nt//HEYSmTiRdFxUVgo1cNqKiBT4EQNCdtq7vpIqG8XFPngObQDWe3xXbWBiVx+1Another example is the predominance of English on the Internet, which can be understood as a contemporary information highway (Figure 4.13). What will happen when other languages begin to challenge the dominance of English on the Internet? This will inevitably happen sooner or later, although whether English will be surpassed by another language is anyone’s guess. For example, although only 23.7 percent of today’s Internet users speak Chinese, from 2000 to 2011, there was 1,478.7 percent growth in the number of Chinese speakers on the Internet. If this trend continues, and when—not if—the 60.8 percent of Chinese speakers who do not now use the Internet begin to log on, we can expect the prevalence of Chinese on the Internet to continue expanding significantly.

Thinking Geographically

Question

HNKEO25++IHWCUi3uhPtUSgK5iz41v04EYAdwleNT7NvhkQYjv6UawGdWv3HUINtA7xaKR++MP2g9JOQ6gehxhzIBE7gZlyz5xlCJoZK8mVvQeIOrtvqmk6718tuzT3eTP/G8g==Language and Cultural Survival

Language and Cultural Survival

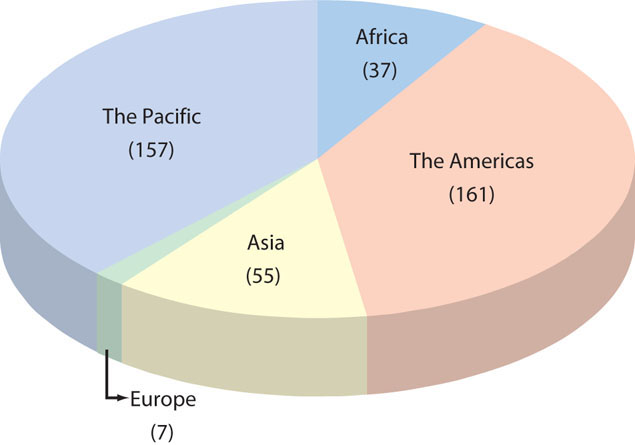

Because language is the primary way of expressing culture, if a language dies out, there is a good chance that the culture of its speakers will too. Some languages, like animal species, are classified as endangered or extinct. Endangered languages are those that are not being taught to children by their parents and are not being used actively in everyday matters. Some linguists believe that more than half of the world’s roughly 6000 languages are endangered. Ethnologue, an online language resource (see Linguistic Geography on the Internet at the end of the chapter for this web site address), considers 417 world languages to be nearly extinct. Languages that have only a few elderly speakers still living fall into this category. Today the Americas and the Pacific regions together account for more than three-quarters of the world’s nearly extinct languages, thanks to their many and varied indigenous language groups. In Argentina, for example, only five families speak Vilela, and only seven or eight speakers of Tuscarora remain in Canada. When these speakers die, it is likely that their language will die out with them.

110

language hotspot A place on Earth that is home to a unique, misunderstood, or endangered language.

As Figure 4.14 shows, almost 40 percent of the world’s nearly extinct languages are found in the Americas. They include a wealth of Native American languages that are slowly becoming suffocated by English, Spanish, and Portuguese. Other language hotspots—places with unique, misunderstood, or endangered tongues—are located around the globe (Figure 4.15). Two of the world’s five most vulnerable regions—northern Australia, central South America, North America’s upper Pacific coast, eastern Siberia, and Oklahoma—are located in the United States.

Thinking Geographically

Question

ZFWzXB/84SEdT05+/X4TFVw6JBJfDQCfVVxr6EXQ2QiirOMXyRh7sG9AyzhA9cD/ih0PQcLHeIzTiruaBDD2UbZZwbtb8pLlXlr/H7A4XkHzYBjrXDza5RchWM7HUvQX

Thinking Geographically

Question

Um2s9kNI3M3CeRZkNiFUOn/r4kQnFDR1AjGQTlgwLu/3PHSrdhZp+USVxYC588ESTp2jQ80ncnZMjKRGCMTZp+4iINIQXNWoz73WeKQIX1tnHdy9xUb9N2X4n3KMdauT/mCLV8qsBUtVTUu7vB5DK9mzJZU28DGe4bfCcNpOFIdpRU6xRelated to linguistic extinction is the existence of so-called remnant languages that survive, typically in small linguistic islands that are surrounded by the dominant language. One example is Khoisan, found in the Kalahari Desert of southwestern Africa and characterized by distinctive clicking sounds. The pockets of Khoisan seen in Figure 4.1 survived after the expansion of the Bantu, discussed earlier (see Figure 4.4). Other remnant languages include Dravidian, spoken by hundreds of millions of people in southern India, adjacent northern Sri Lanka, and a part of Pakistan, as well as Australian Aborigine, Papuan, Caucasic, Nilo-Saharan, Paleosiberian, Inuktitut, and a variety of Native American language families. In a few cases, individual minor languages represent the sole survivors of former families. Basque, spoken in the borderland between Spain and France, is such a survivor, unrelated to any other language in the world.

Texting and Language Modification

Texting and Language Modification

Though English dominates the Internet (see Figure 4.13), much of what comes across our computer and cell phone screens isn’t a readily recognizable form of English. As with the diffusion of spoken English to far-flung regions of the British Empire, the English language that is spread via electronic correspondence is subject to significant modification. E-mailing, instant messaging, and text messaging Standard English on cell phones requires a lot of typing, and text is notoriously deficient in conveying emotions when compared to the spoken word. For these reasons, users often use abbreviations and symbols to decrease the number of keystrokes used, to add emotional punctuation to their correspondence, and to make electronic communication hard to monitor by those who don’t understand the language—particularly parents and teachers.

111

English is an alphabetic writing system; its letters represent discrete sounds that must be strung together to form a word’s complete sound. English-speaking texters quickly learn to take shortcuts around the lengthiness inherent to alphabetic writing. The simplest and most commonly used shortcut involves using abbreviations instead of whole words to convey common phrases. POS (parent over shoulder), AFK (away from keyboard), VBG (very big grin), LOL (laughing out loud), and GMTA (great minds think alike) are some examples of this technique. Another shortcut involves using characters that sound like words. For example, the number “8” can substitute for the word or sound “ate,” so “h8” is “hate,” and “i 8” is “I ate.” As your instructor for this class will likely confirm, such abbreviations and symbols have even worked their way into term papers at the college level, much to the consternation or delight of language scholars.

In texting, the use of symbols such as ☺ and ♥, which are called pictograms (word pictures), is similar to Chinese writing. Their popularity has resulted in a vast lexicon of pictograms as well as symbol groupings, called emoticons, used to convey entire words, ideas, and emotions in a compact and often humorous form. Here are some examples:

| :) | (user is smiling or joking) |

| :@ | (user is screaming or cursing) |

| :# | (well, shut my mouth!) |

Although the meaning of these symbols is understood by speakers of many languages because of their ubiquity, non-English languages also employ their own symbol combinations. In Korean, for instance, ^^ is used instead of :) to convey a smiling face and -_- is used instead of :( to depict a sad face. In Chinese, the number 5 is pronounced in a way that resembles crying, so “555” is the Chinese texter’s way of conveying sadness.