Political Diffusion

Political Diffusion

Do political ideas, institutions, and countries expand and spread by means of cultural diffusion? Absolutely! Political events and developments can trigger massive human migrations, sometimes spanning continents. However, political boundaries also act as barriers to the movement of people, ideas, knowledge, and resources.

6.0.4 Movement Between Core and Periphery

Movement Between Core and Periphery

core area The territorial nucleus from which a country grows in area and over time, often containing the national capital and the main center of commerce, culture, and industry.

Many independent states sprang fully grown into the world, but some expanded outward when powerful political entities emerged from a small nucleus called a core area. These core political powers enlarged their territories by annexing adjacent lands, often over many centuries. Generally, core areas possess a particularly attractive set of resources for human life and culture. Larger numbers of people cluster there than in surrounding districts, especially if the area has some measure of natural defense against aggressive neighboring political entities. This denser population, in turn, may produce enough wealth to support a large army, which then provides the base for further expansion outward from the core area. Resources, people, and capital investment begin to flow between the core and peripheral territories, usually resulting in a further consolidation of the core’s wealth and power.

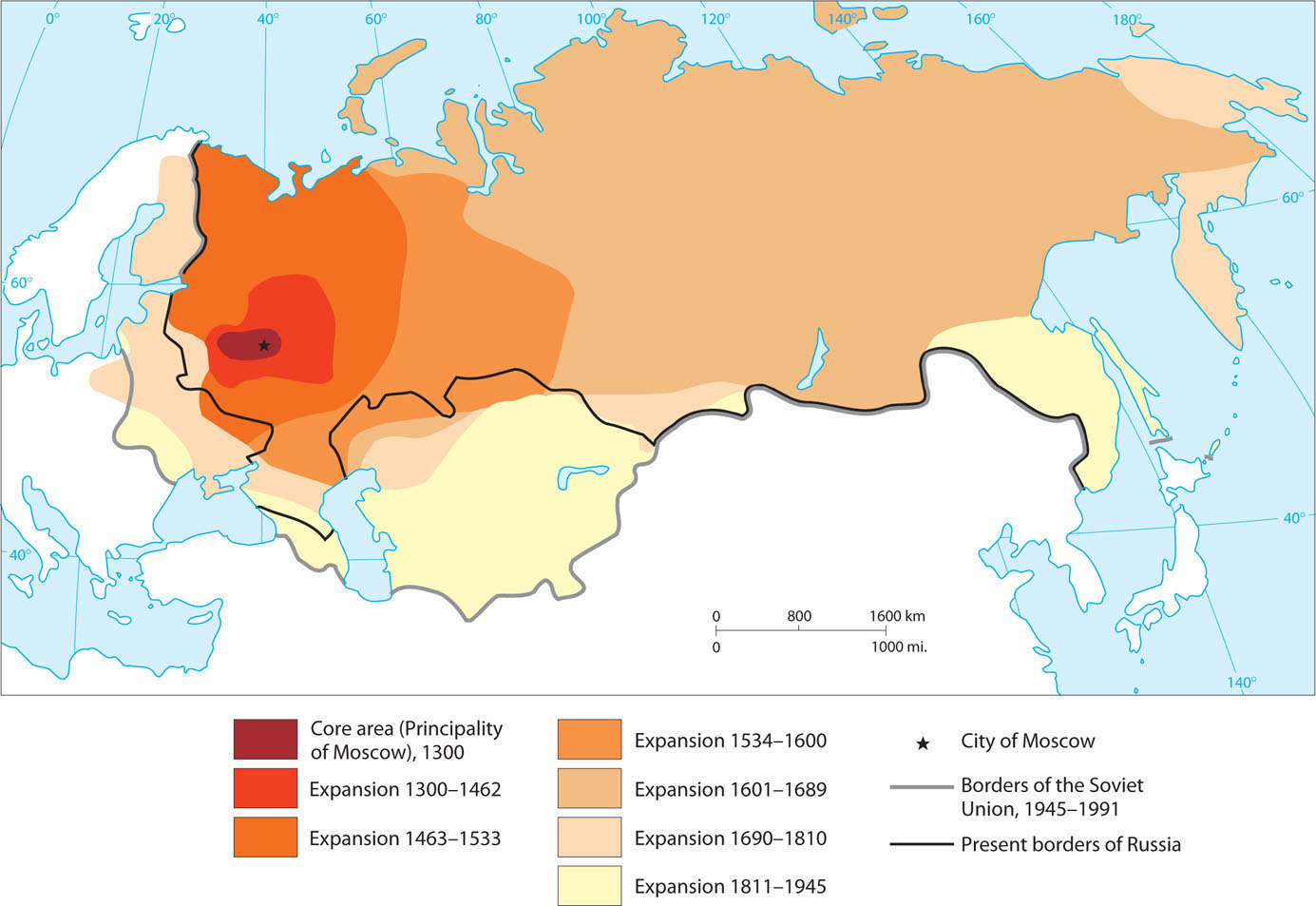

In states formed in this way, the core area typically remains the country’s single most important district, housing the capital city and the cultural and economic heart of the nation. The core area is the node of a functional region. France expanded to its present size from a small core area around the capital city of Paris. China grew from a nucleus in the northeast, and Russia originated in the small principality of Moscow (Figure 6.10). The United States grew westward from a core between Massachusetts and Virginia on the Atlantic coastal plain, an area that still has the national capital and the densest population in the country.

Thinking Geographically

Question 6.11

bpnm8LFwuNGmbRHr/cEon73QIcJbcID3zHkyeA9KEFFSiNce8Jzl2U3PYhK0DbLW2h34tPkcC1xZFaYujeRevjmyBjzIJHJIUxRvKAG7+E24mKHoxe6fGHYlouToJ1jKcaz15EehM7/ht0rPPcu/bhtLnGQFXp/ZbV9JbvLXhJ8zQGQcR7BgTK9Xf4vM7dFT70fmPGP8qb8t3NEKNXQWML+6hiy4HAy+162

The evolution of independent countries in this manner produces the core-periphery configuration, described in Chapter 1 as typical of both functional and formal regions. Although the core dominates the periphery, a certain amount of friction exists between the two. Peripheral areas generally display pronounced, self-conscious regionality and occasionally provide the settings for secession movements. Even so, countries that diffused from core areas are, as a rule, more stable than those created all at once to fill a political void. The absence of a core area can blur or weaken citizens’ national identity and make it easier for various provinces to develop strong local or even foreign allegiances. Belgium and the Democratic Republic of the Congo offer examples of countries without political core areas. In the case of the Congo, this situation partly accounts for the history of secessionist conflicts and internecine wars since the country gained independence from colonial rule in 1960.

Countries with multiple, competing core areas are potentially the least stable of all. This situation often develops when two or more independent countries are united. The main threat is that one of the competing cores will form the center of a separatist movement and break apart the country. In Spain, Castile and Aragon united in 1479, but tensions in the union remain more than five centuries later—in part because the old core areas of the two former countries, represented by the cities of Madrid and Barcelona, continue to compete for political control and cultural influence. That these two cities symbolize two language-based cultures, Castilian and Catalan, compounds the division.

6.0.5 Diffusion and Political Innovation

Diffusion and Political Innovation

One of the consequences of colonialism was the creation of new patterns of mobility among the conquered populations. One pattern in particular contained the seeds of colonialism’s demise. Colonial rule in Africa depended on the establishment of a relatively small cadre of educated African civil servants. The colonial rulers selected those whom they considered the best and the brightest (and most politically cooperative) among their African subjects and sent them to the best universities in Europe. In addition to learning the skills required of colonial functionaries, they absorbed the ideals of Western political philosophy, such as the right of self-determination, independent self-rule, and individual rights. Educated Africans returned to their countries armed with these ideas and organized new nationalist movements to oppose colonial rule.

163

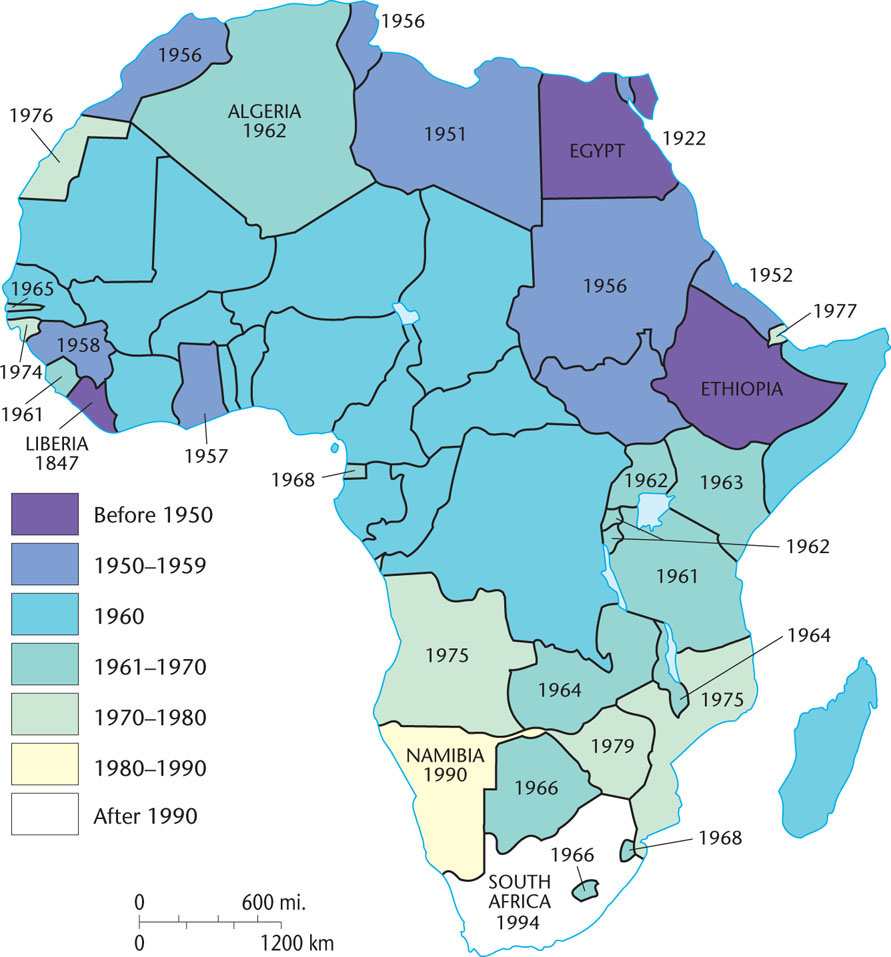

The consequences can be seen in the spread of political independence in Africa. In 1914, only two African countries—Liberia and Ethiopia—were fully independent of European colonial or white minority rule, and even Ethiopia later fell temporarily under Italian control. Influenced by developments in India and Pakistan, the Arabs of North Africa began a movement for independence. Their movement gained momentum in the 1950s and swept southward across most of the African continent between 1960 and 1965. Many of Africa’s great nationalist leaders of this period obtained university degrees in England, Scotland, France, and other European countries. By 1994, African nationalists had helped spread the idea of independence into all remaining parts of the continent, eventually reaching the Republic of South Africa, formerly under white minority rule (Figure 6.11).

Thinking Geographically

Question 6.12

fqpWUkPEn43D8qqtJGlmudub7iGCKR9ubGVNDHW1+7nsNdBbgA6XCM/jqRTzXZPUkfF7DKwrGUdjqf04hoeGVnHFtd/AhNHzVBDJatiCwebIHUaahR4HnLQZ21M1TGK/KeeToc8zFOQ=Despite its rapid spread, diffusion of African self-rule occasionally encountered barriers. Portugal, for example, clung tenaciously to its African colonies until 1975, when a change in government in Lisbon reversed a 500-year-old policy, allowing the colonies to become independent. In colonies containing large populations of European settlers, independence came slowly and usually with bloodshed. France, for example, sought to hold on to Algeria because many European colonists had settled there. The country nonetheless achieved independence in 1962, but only after years of violence. In Zimbabwe, a large population of European settlers refused London’s orders to move toward majority rule, resulting in a bloody civil war and delaying the country’s independence until 1979.

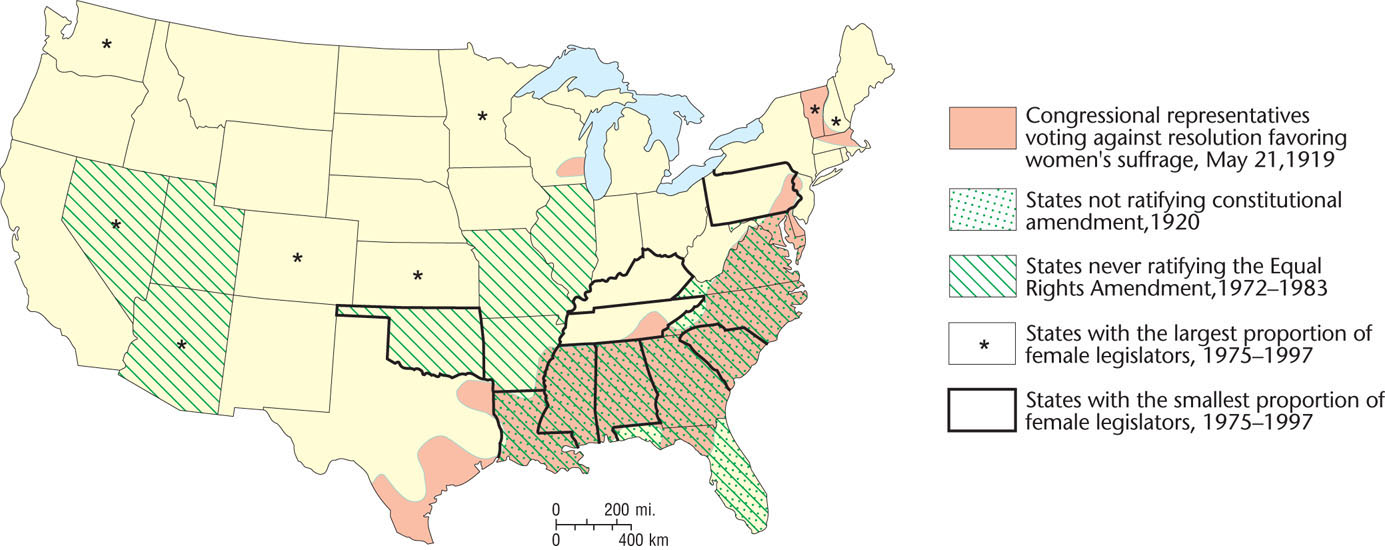

On a quite different scale, political innovations also spread within independent countries. American politics abounds with examples of cultural diffusion. A classic case is the spread of suffrage for women, a movement that culminated in 1920 with the ratification of a constitutional amendment (Figure 6.12). Opposition to women’s suffrage was strongest in the U.S. South, a region that later exhibited the greatest resistance to ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment and displayed the most reluctance to elect women to public office.

Thinking Geographically

Question 6.13

IIriIDvCOhxxInzG7R91wemyZgk2zPvR2AKZ6dC5zLl6Ui7xjnP7HEVCNsaikTjiNYZKBpSKYYxh5xL3+IOvbi2BKjOVneP88WqcPw==Federal statutes permit, to some degree, laws to be adopted in the individual functional subdivisions. In the United States and Canada, for example, each state and province enjoys broad lawmaking powers, vested in the legislative bodies of these subdivisions. The result is often a patchwork legal pattern that reveals the processes of cultural diffusion at work. A good example is the clean air movement, which began in California with the initiation of state legislation regulating automotive and industrial emissions. It later spread to other states and provided the model for clean air legislation at the federal level.

164

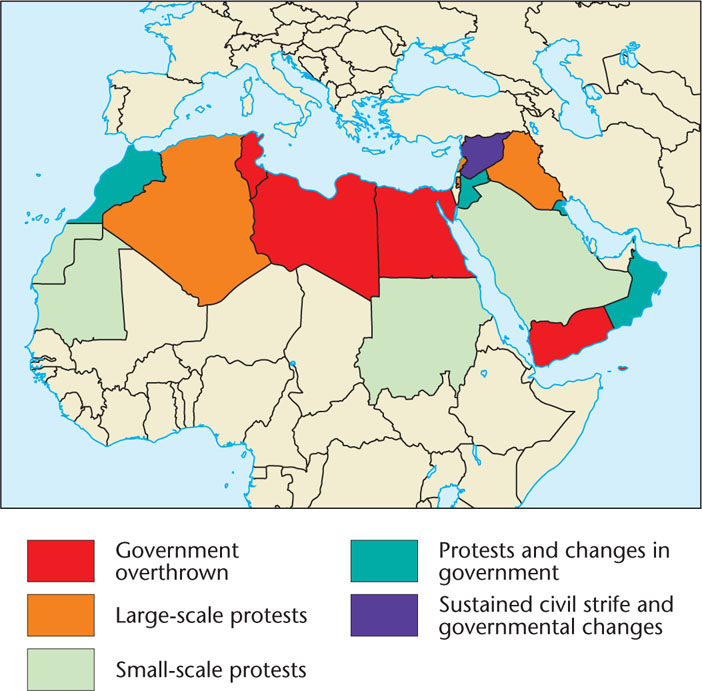

In recent decades, patterns in the initiation and organization of political change have begun to supersede state, provincial, and even national boundaries due to the increasing influence of the Internet. An important example of this shift in the diffusion of political activism and change began in December 2010 in Tunisia, where students and other dissatisfied citizens protested perceived state attempts to repress the population and to censor the Internet. These protests sparked a wave of similar demonstrations in many other Middle Eastern states, with the series of protests collectively coming to be known as the Arab Spring. The majority of these protests incorporated civil-resistance techniques such as strikes, marches, and rallies. These events were largely organized, and subsequently documented, primarily through social media on the Internet. The Internet allowed not only instantaneous communication among protestors but also the ability to raise awareness and garner support within specific countries and around the world. The ousting of national leaders in several Middle Eastern countries and significant governmental changes enacted in other states within the region attest to the power of the Internet as a tool for organizing people from diverse backgrounds for political purposes (Figure 6.13).

Thinking Geographically

Question 6.14

g/bHBys0tFsesH83X74o50G5ofQOce98lsbM7zJTw5i7d69kKRdOHJ0jVU/4dpXlw11wMOV5aggs+FDGEN/swsIZsWUcXjK3ksvzOMoftJHAhD4Ddbzdu9yd25Rztg17AJDKLcPxjvaV5Gu0QgGVRC0jw+k=165

The Internet and social media played a significant role in another mass political movement known as Occupy Wall Street (OWS). In July 2011, taking inspiration from the Arab Spring, the anticonsumerism magazine Adbusters posted a suggestion on Twitter for a protest march in Lower Manhattan. This protest was intended to highlight perceived mass social injustices against the 99 percent of the population struggling with student debt, rising health-care costs, and foreclosure by the 1 percent of greedy and corrupt capitalists and government officials. In the months following this tweet, hundreds of thousands of protesters used Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and other social networking sites to spread the OWS message globally. The capacity to stream live video on the Internet in conjunction with these social networking sites propelled the OWS movement to unprecedented global visibility. The Internet allowed organizers of and participants in the movement to get up-to-the-minute information about Occupy protests around the world; it also provided them with virtual places to talk about the images they were seeing. In this way, OWS established itself as a “leaderless movement” composed of individuals from many different political persuasions and national backgrounds.

6.0.6 Politics and Migration

Politics and Migration

Very often, political decisions or events provide the motivation for migration, both voluntary and forced. A contemporary example of political migration occurred in the Gambella region of western Ethiopia beginning in 2008. At that time, the state began to relocate tens of thousands of indigenous peoples living in this rich agricultural region to less fertile agricultural lands in other regions of the country. This migration was officially voluntary, with the government promising to compensate indigenous landowners and to provide health care and education in the new villages. However, many of the people who complied with the relocation program have faced food and water shortages and a lack of basic services in their new home. Cases of endemic hunger and starvation in these settlements have even been reported. Rather than face these conditions, many people fled to refugee camps in nearby Kenya.

The Ethiopian government has officially denied that the Gambella relocation is connected to the leasing of the vacated fertile lands at lucrative rates to foreign investors and wealthy Ethiopian businesspeople. Instead, state officials maintain that the program is designed to find alternative livelihoods for citizens who were not properly farming the fertile lands to grow cash crops. These differing claims have drawn the attention of international human rights watchdog groups, which have called for the suspension of the program until investigations of alleged threats, assaults, and arrests can be conducted. Further, some human-rights organizations fear that humanitarian funding to Ethiopia has been used, in part, to finance the Gambella displacements and to suppress growing political dissent. No matter how these disputes play out, it can be stated with certainty that political decisions to motivate, or forcibly conduct, mass migrations leave lasting imprints on the physical and cultural landscape.