Religious Diffusion

Religious Diffusion

culture hearth A focused geographic area where important innovations are born and from which they spread.

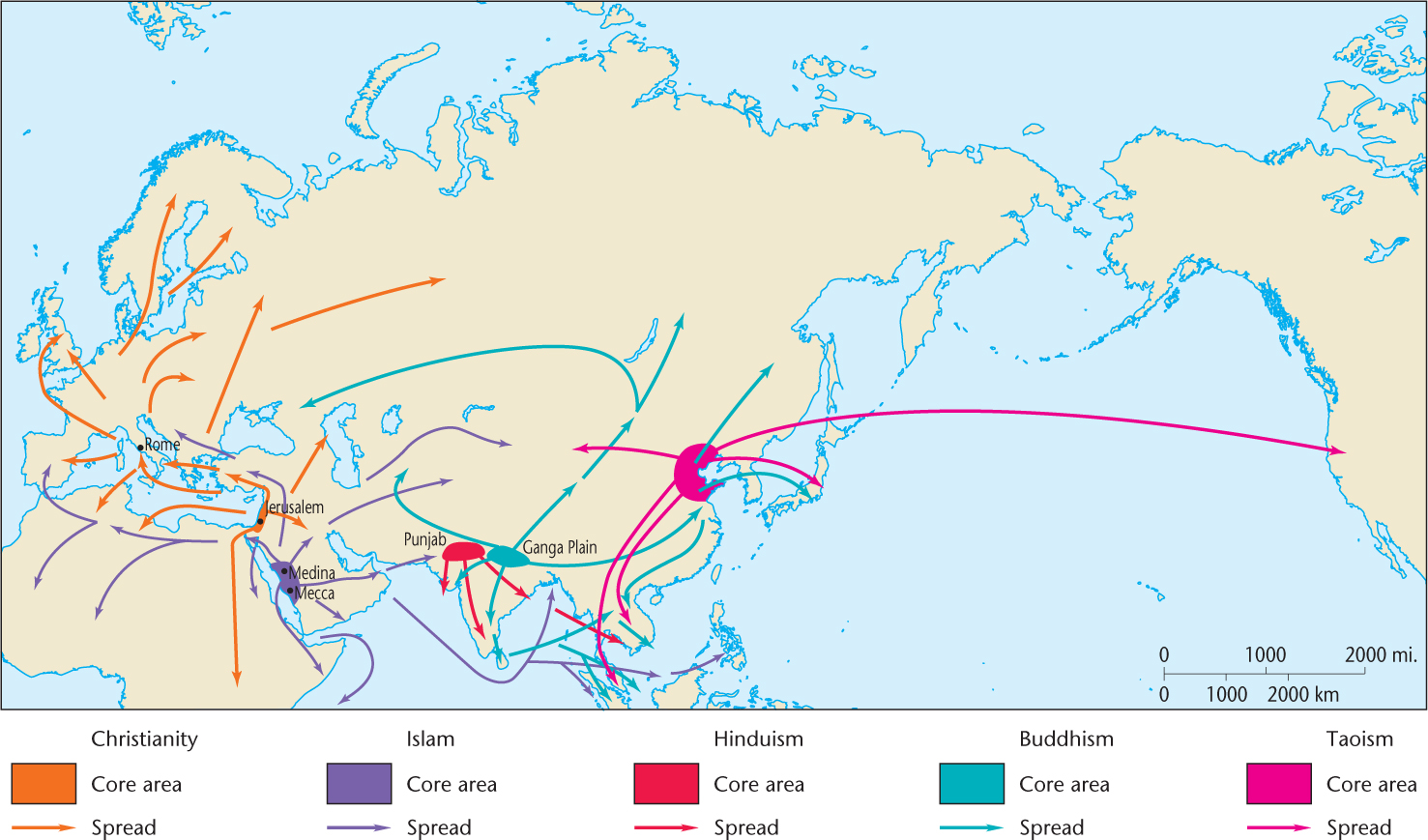

How did the geographical distribution of religions and denominations, of regions and places, come about? What roles did hierarchical and contagious diffusion play? The spatial patterning of religions, denominations, and secularism is the product of innovation and cultural diffusion. To a remarkable degree, the origin of the major religions was concentrated spatially in three principal culture hearth areas (Figure 7.12). A culture hearth is a focused geographic area where important innovations are born and from which they spread. Many religions mandate periodic return of the faithful to these culture hearths in order to confirm or renew their faith.

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.12

drwgdLWuEyDFYq4olicoA5uCHG14/upXDkIrhduhDCTmB3C5LA9cE0K2H8xGeEtidR+GdNoqMx1G/ItTYBDgsEtLiRnKnzxEE1zaqPY/pvwZV/pS91bURgyCKFw=The Semitic Religious Hearth

The Semitic Religious Hearth

All three of the great monotheistic faiths—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—arose among Semitic peoples who lived in or on the margins of the deserts of southwestern Asia, in the Middle East (see Figure 7.12). Judaism, the oldest of the three, originated some 4000 years ago. Only gradually did its followers acquire dominion over the lands between the Mediterranean and the Jordan River—the territorial core of modern Israel. Christianity, child of Judaism, originated there about 2000 years ago. Seven centuries later, the Semitic culture hearth once again gave birth to a major faith when Islam arose in western Arabia, partly from Jewish and Christian roots.

Religions spread by both relocation and expansion diffusion. Recall from Figure 1.10 that expansion diffusion can be divided into hierarchical and contagious subtypes. In hierarchical diffusion, ideas become implanted at the top of a society, leapfrogging across the map to take root in cities and bypassing smaller villages and rural areas. Because their main objective is to convert nonbelievers, proselytic faiths are more likely to diffuse than ethnic religions, and it is not surprising that the spread of monotheism was accomplished largely by Christianity and Islam, rather than Judaism. From Semitic southwestern Asia, both of the proselytic monotheistic faiths diffused widely.

179

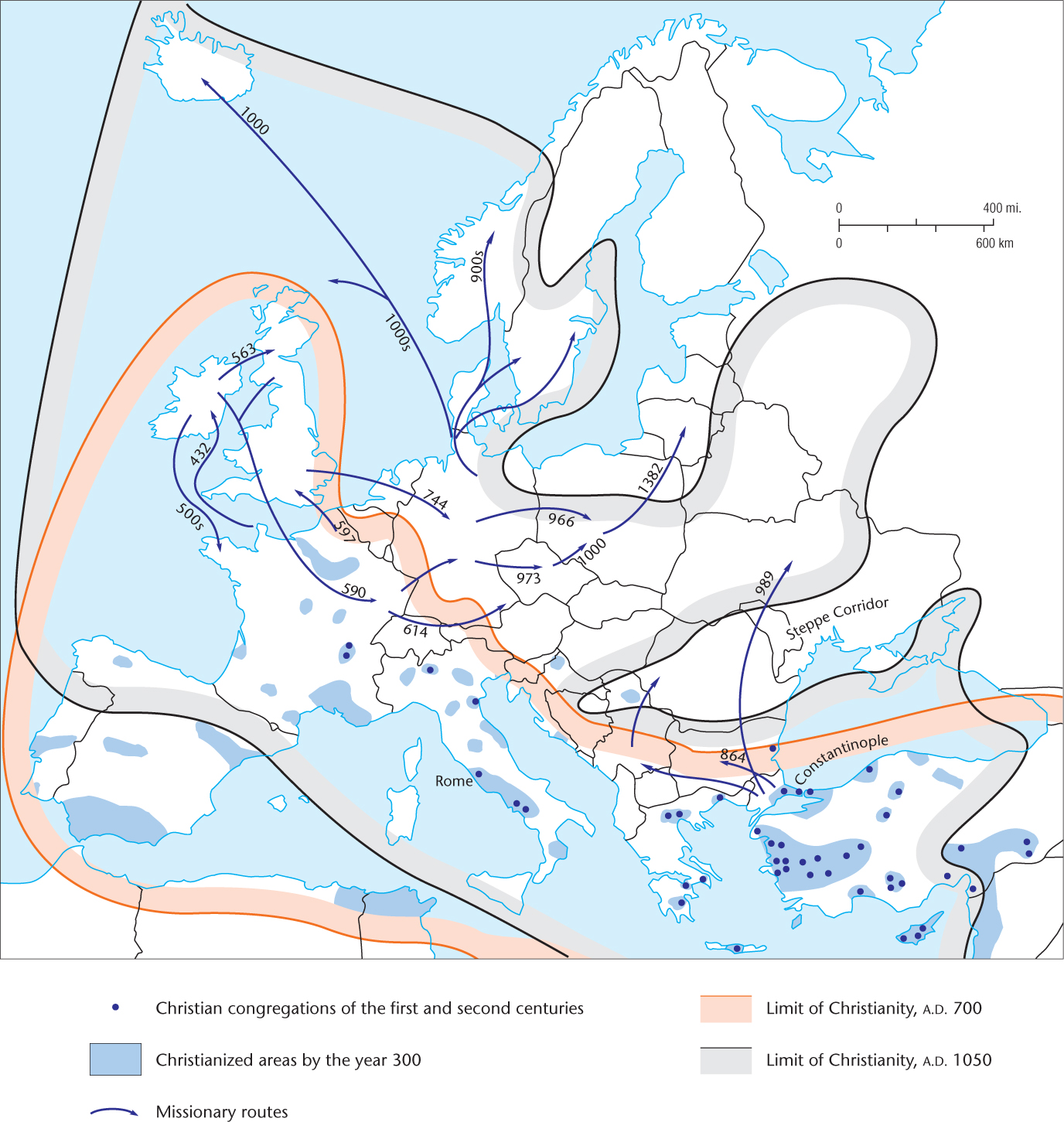

Christians, observing the admonition of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew—“Go ye therefore and teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost, teaching them to observe all things whatsoever I have commanded you”—initially spread through the Roman Empire, using the splendid system of imperial roads to extend the faith. In its early centuries of expansion, Christianity displayed a spatial distribution that clearly reflected hierarchical diffusion (Figure 7.13). The early congregations were established in cities and towns, temporarily producing a pattern of Christianized urban centers and pagan rural areas. Indeed, traces of this process remain in our language. The Latin word pagus, “countryside,” is the root of both pagan and peasant, suggesting the ancient connection between non-Christians and the countryside.

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.13

Ro46tYKRiwu7xzbR7sECV5ooCsBBEhdbUFHDOfAz38Dot5wix2atGksoKU4bUVILKLyTU8JhX6PopD+2037tS7xGkUveqS/MnS0box8hipLO/JrxpRcGQ6UhfQW5AP1tWgVOz2xFLZaKTHPd0gT1UIGt5WFfPAs9dda0SkGoaJr8ZlgU5JJH9ED/+gBib6ysBknFs/3Bom6pXbaicontact conversion The spread of religious beliefs by personal contact.

The scattered urban clusters of early Christianity were created by such missionaries as the apostle Paul, one of Jesus’ disciples who moved from town to town bearing the news of the emerging faith. In later centuries, Christian missionaries often used the strategy of converting kings or tribal leaders, setting in motion additional hierarchical diffusion. The Russians and Poles were converted in this manner. Some Christian expansion was militaristic, as in the reconquest of Iberia from the Muslims and the invasion of Latin America. Once implanted in this manner, Christianity spread farther by means of contagious diffusion. When applied to religion, this method of spread is called contact conversion and is the result of everyday associations between believers and nonbelievers.

The Islamic faith spread from its Semitic hearth area in a predominately militaristic manner. Obeying the command in the Qur’an that they “do battle against them until there be no more seduction from the truth and the only worship be that of Allah,” the Arabs expanded westward across North Africa in a wave of religious conquest. The Turks, once converted by the Arabs, carried out similar Islamic conquests. In a different sort of diffusion, Muslim missionaries followed trade routes eastward to implant Islam hierarchically in the Philippines, Indonesia, and the interior of China. Tropical Africa is the current major scene of Islamic expansion, an effort that has produced competition with Christians for the conversion of animists. As a result of missionary successes in sub-Saharan Africa and high birth rates in its older sphere of dominance, Islam has become the world’s fastest-growing religion in terms of the number of new adherents.

The Indus-Ganges Hearth

The Indus-Ganges Hearth

The second great religious hearth area lies in the plains fringing the northern edge of the Indian subcontinent. This lowland, drained by the Ganges and Indus rivers, gave birth to Hinduism and Buddhism. Hinduism, which is at least 4000 years old, was the earliest faith to arise in this hearth. Its origin apparently lay in Punjab, from which it diffused to dominate the subcontinent, although some historians believe that the earliest form of Hinduism was introduced from Iran by emigrating Indo-European tribes about 1500 b.c. Missionaries later carried the faith, in its proselytic phase, to overseas areas, but most of these converted regions were subsequently lost to other religions.

Branching off from Hinduism, Buddhism began in the foothills bordering the Ganges Plain about 500 b.c. (see Figure 7.12). For several centuries it remained confined to the Indian subcontinent, but missionaries later carried the religion to China (100 b.c. to a.d. 200), Korea and Japan (a.d. 300 to 500), Southeast Asia (a.d. 400 to 600), Tibet (a.d. 700), and Mongolia (a.d. 1500). Buddhism developed many regional forms throughout Asia, except in India, where it was ultimately accommodated within Hinduism.

The diffusion of Buddhism, like that of Christianity and Islam, continues to the present day. It is estimated that some 1.2 million Buddhists live in the United States today, many in Southern California. Mostly, their presence is the result of relocation diffusion by Asian immigrants to the United States, where immigrant Buddhists outnumber Buddhist converts by three to one.

The East Asian Religious Hearth

The East Asian Religious Hearth

Kong Fu-tzu and Lao Tzu, the respective founders of Confucianism and Taoism, were contemporaries who reputedly once met with each other. Both religions were adopted widely throughout China only when the ruling elite promoted them. In the case of Confucianism, this was several centuries after the master’s death. During his life, Kong Fu-tzu wandered about with a small band of disciples trying to persuade rulers to put his ideas on good governance into practice. He was shunned even by lowly peasants, who criticized him as “a man who knows he cannot succeed but keeps trying.” Thus, early attempts at contagious diffusion were unsuccessful, whereas hierarchical diffusion from politicians and schools spread Confucianism from the top down. Taoism, as well, did not gain wide acceptance until it was promoted by the ruling Chinese elite.

179

After 1949, China’s communist government officially repressed organized religious expression, dismissing it as a relic of the past. In other words, the government attempted to erect an absorbing barrier that would not only halt the spread of religion but that also would erase it from Chinese public and private life. As noted in Chapter 1, absorbing barriers are rarely completely successful, and this example is no exception. Although temples were converted to secular uses and even looted and burned, religion was driven underground rather than eradicated. After the end of the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), which aimed to purify Chinese society of bourgeois excesses such as religion, tolerance for religious expression grew. However, the Chinese Communist Party’s official stance still holds that religious and party affiliations are incompatible; thus, some party officials are reluctant to divulge their religious status. This, combined with the fact that many Chinese practice elements of several Taoic faiths simultaneously, makes the precise enumeration of adherents difficult.

179

Taoism and Confucianism have spread with the Chinese people through trade and military conquest. Thus, people in Taiwan, Malaysia, Singapore, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, along with mainland China, practice these beliefs or at the least have been influenced by them. Today, Chinese and Japanese migrants alike have relocated their belief systems across the globe, as the image of the Tsubaki Shinto Shrine in Washington State in Figure 7.14 confirms.

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.14

cddYyygwNwHk2l+0YoBGxSpfw7loEZWAo7Hp/V+Vcf40UOCPpI1+Vyt00t+jczF3EERC+nFEqOU16rf5e+RTTcgtjL+2v6fIvo2l+4SjY6Fn7Hg4Reflecting on Geography

Question 7.15

RsflLBvNRbcmUQ9QBJk/+xP6oeyR7b0ss2l5vdN0Dz7YNrew3AuqOISNix/LAGheTLapsnWIL5qAxkN4MEkq8fp1JYza4dcp4VCS0IDCPNHEhhP+E1uUPq2LCrJDgB8MU4PrtSk62bo=Barriers and Time-Distance Decay

Barriers and Time-Distance Decay

Religious ideas move in the manner of all innovation waves. They weaken with increasing distance from their places of origin and with the passage of time. Barriers are usually of the permeable type, allowing part of the innovation to diffuse through it but weakening it and retarding its spread. An example is the partial acceptance of Christianity by various Indian groups in Latin America and the western United States, which serves in some instances as a camouflage behind which many aspects of the tribal ethnic religions survive. In fact, permeable barriers are normally present in the expansion diffusion of religious faiths. Most religions are modified by older, local beliefs as they diffuse spatially. Rarely do new ideas, whether religious or not, gain unqualified acceptance in a region.

179

Absorbing barriers can also exist in religious diffusion. The attempt to introduce Christianity into China provides a good example. When Catholic and Protestant missionaries reached China from Europe and the United States, they expected to find millions of people ready to receive the Word of God. However, they had crossed the boundaries of a culture region thousands of years old, in which some basic social ideas left little opening for Christianity and its doctrine of original sin. The Christian image of humankind as flawed, of a gap between creator and created, of the Fall and the impossibility of returning to godhood, was culturally incomprehensible to the Chinese. Only in the early twentieth century, as China’s social structure crumbled under Western assault, did a significant, though small, number of Chinese convert to Christianity. Many of these were “rice Christians,” poor Chinese willing to become Christians in exchange for the food that missionaries gave them.

In addition, religion itself can act as a barrier to the spread of nonreligious innovations. Religious taboos can even function as absorbing barriers, preventing diffusion of foods, drinks, and practices that violate the taboo. Mormons, who are forbidden to consume products that contain caffeine, have not taken part in the American fascination with coffee. Sometimes these barriers are permeable. Certain Pennsylvania Dutch churches, for example, prohibit cigarette smoking but do not object to member farmers raising tobacco for sale in the commercial market.