Agricultural Landscapes

Agricultural Landscapes

agricultural landscape The cultural landscape of agricultural areas.

What is the agricultural component of the cultural landscape? What might we learn about agriculture by examining its unique landscape? According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, 37.3 percent of the world’s land area is cultivated or pastured. In this huge area, the visible imprint of humankind might best be called the agricultural landscape. The agricultural landscape often varies even over short distances, telling us much about local cultures and subcultures. Moreover, it remains in many respects a window on the past, and archaic features abound. For this reason, the traditional rural landscape can teach us a great deal about the cultural heritage of its occupants.

Survey, Cadastral, and Field Patterns

Survey, Cadastral, and Field Patterns

cadastral pattern The shapes formed by property borders; the pattern of land ownership.

survey pattern A pattern of original land survey in an area.

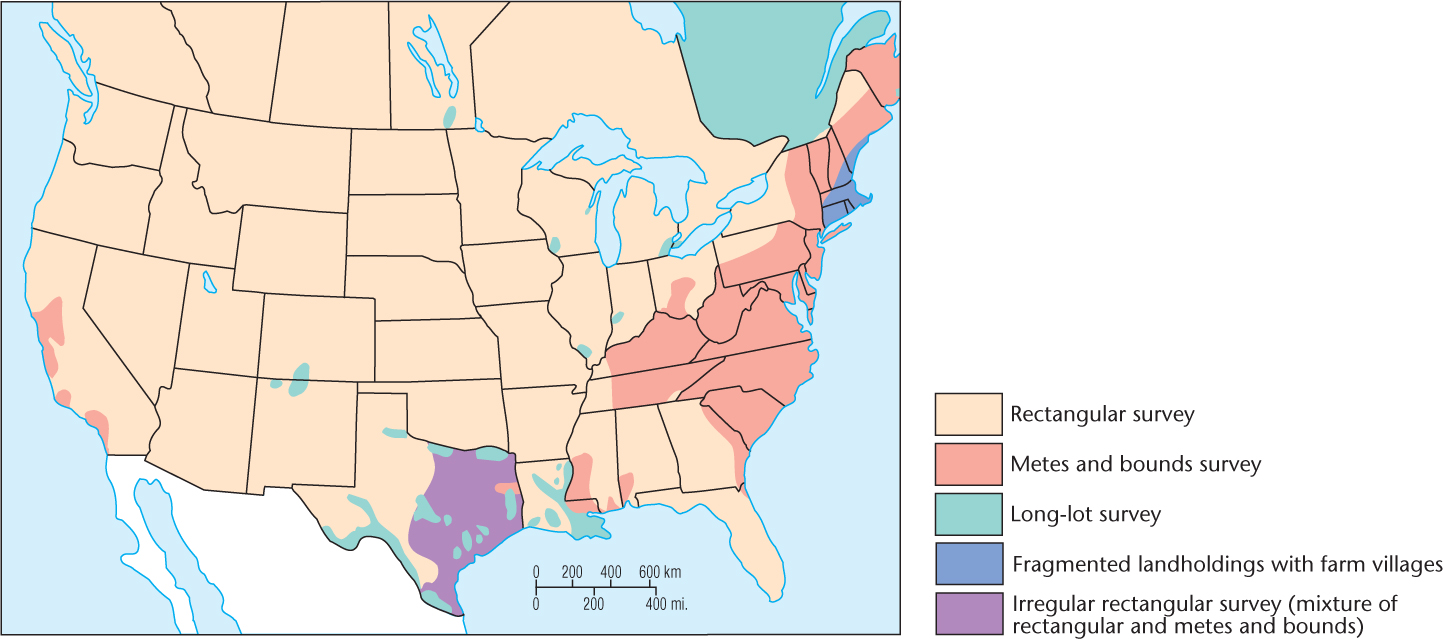

A cadastral pattern is one that describes property ownership lines, whereas a field pattern reflects the way that a farmer subdivides land for agricultural use. Both can be greatly influenced by survey patterns, the lines laid out by surveyors prior to the settlement of an area. Major regional contrasts exist in survey, cadastral, and field patterns, for example, unit-block versus fragmented landholding and regular, geometric survey lines versus irregular or unsurveyed property lines.

hamlet A small rural settlement, smaller than a farm village.

Fragmented farms are the rule in the Eastern Hemisphere. Under this system, farmers live in farm villages or smaller hamlets. Their landholdings lie splintered into many separate fields situated at varying distances and lying in various directions from the settlement. One farm can consist of 100 or more separate, tiny parcels of land (Figure 8.30). The individual plots may be roughly rectangular, as in Asia and southern Europe, or they may lie in narrow strips. The latter pattern is most common in Europe, where farmers traditionally worked with a bulky plow that was difficult to turn. The origins of the fragmented farm system go back to an early period of peasant communalism. One of its initial justifications was a desire for peasant equality. Each farmer in the village needed land of varying soil composition and terrain. Travel distance from the village was to be equalized. From the rice paddies of Japan and India to the fields of western Europe, the fragmented holding remains a prominent feature of the cultural landscape.

Thinking Geographically

Question 8.35

p4NxZ9dJwag+1Ieqdh1hFiyMkFi7fegXaiwMrNnS5Xg+Z0ljtTUh8lnN9tbpZMjYIi0KWYYvYy5mfjZ87pfTbC+ff43ZR8cNZNid2g==243

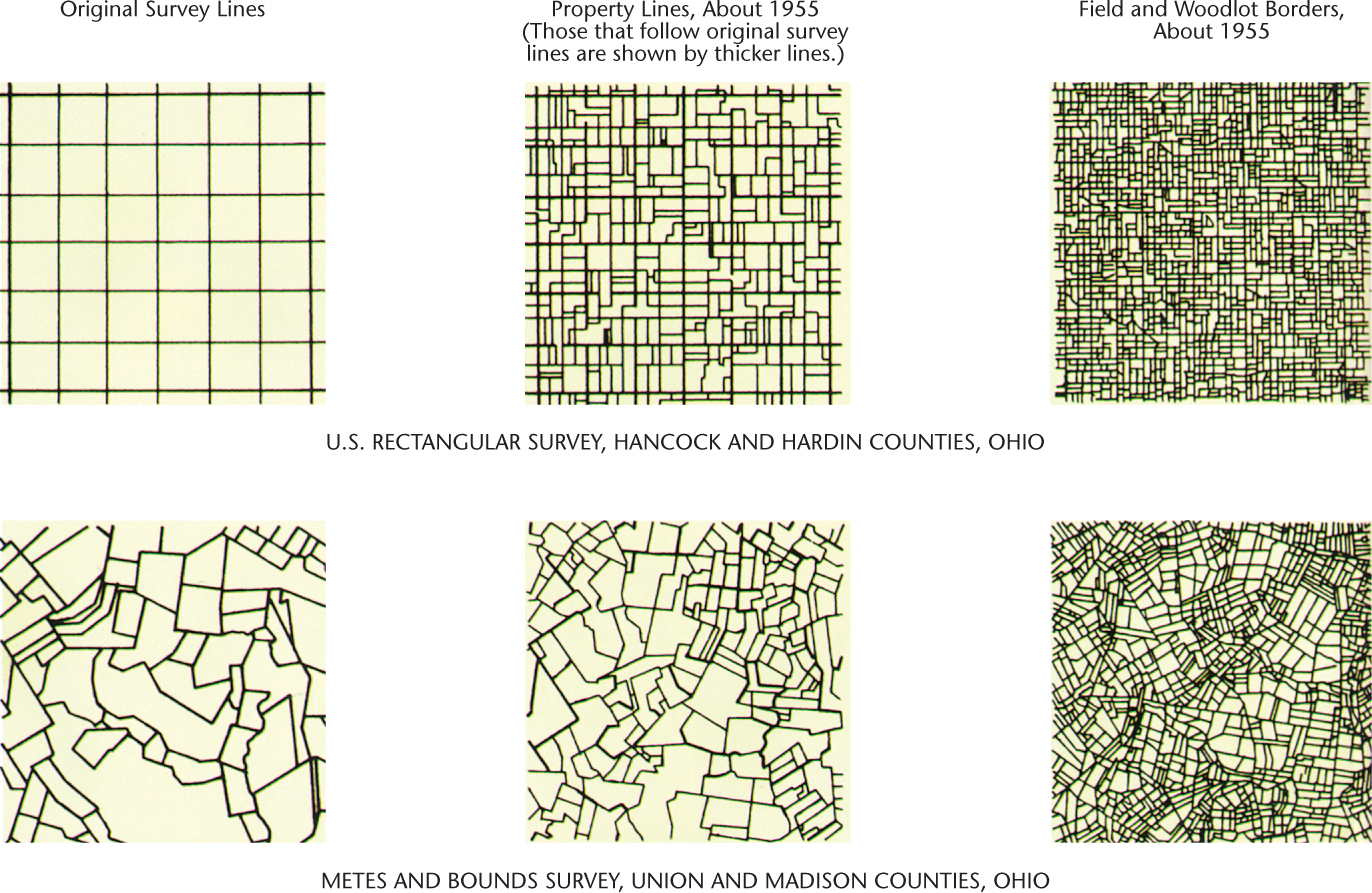

Unit-block farms, by contrast, are those in which all of the farmer’s property is contained in a single, contiguous piece of land. Such forms are found mainly in the overseas area of European settlement, particularly the Americas, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. Most often, they reveal a regular, geometric land survey. The checkerboard of farm fields in the rectangular survey areas of the United States provides a good example of this cadastral pattern (Figure 8.31).

Thinking Geographically

Question 8.36

K2IDyVlHTvN6oQqTKvJQZRp5oElbL4AqBEK6TqKy+rCIrdCzvfgbts2x/WFduBiEp3LtBpISo1TkWA8k7WOE/OiRryiKxot7Ztzp5Sw6S+wWCgOBggRMO27beGAoS/X76l4+YA==The American township and range system, discussed in Chapter 6, first appeared after the Revolutionary War as an orderly method for parceling out federally owned land for sale to pioneers. It imposed a rigid, square graph-paper pattern on much of the American countryside; geometry triumphed over physical geography (Figure 8.32). Similarly, roads follow section and township lines, adding to the checkerboard character of the American agricultural landscape. Canada adopted an almost identical survey system, which is particularly evident in the Prairie Provinces.

Thinking Geographically

Question 8.37

zh5n+30BHkW/1Mt9IhQoE938p3l/+vdJ0f5n+x8oUpBWYBd7P27uuMktCgECukLuJxcEmrVUaQkthkqQt/juY+z2epvNmMdVpQD7Tg==244

Reflecting on Geography

Question 8.38

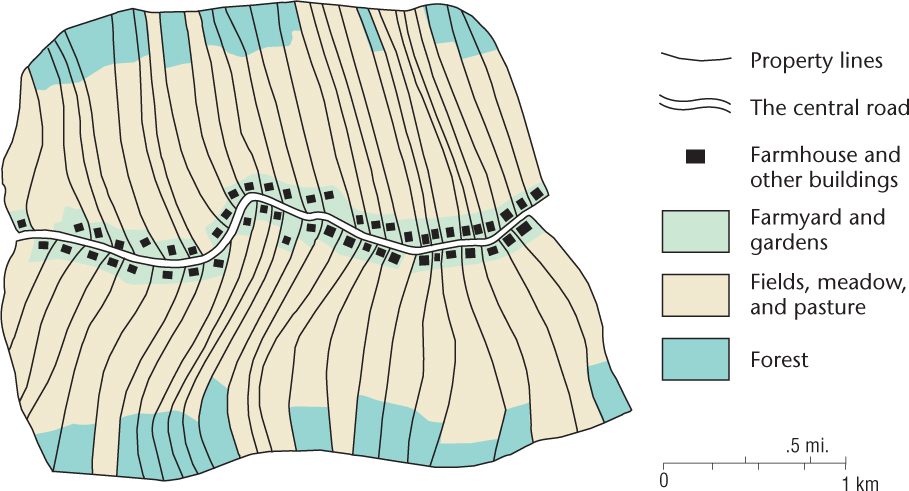

z4itPfWIRZtnpM2iEV57dNMKvpYolMs4zwmBKbztp1WjyOv6DmZFwIeHCcrw5JTYPfgua4ZUBrUX7URHFbujj0gbKv36YFm31NJktjFphCLFvTvL0UhpixdxMDZBYwdNOh8P7blP+KJCzJhECDdU8Q==Equally striking in appearance are long-lot farms, where the landholding consists of a long, narrow unit-block stretching back from a road, river, or canal (Figure 8.33). Long-lots lie grouped in rows, allowing this cadastral survey pattern to dominate entire districts. Long-lots occur widely in the hills and marshes of central and western Europe, in parts of Brazil and Argentina, along the rivers of French-settled Québec and southern Louisiana, and in parts of Texas and northern New Mexico. These unit-block farms are elongated because such a layout provides each farmer with fertile valley land, water, and access to transportation facilities, either roads or rivers. In French America, long-lots appear in rows along streams, because waterways provided the chief means of transport in colonial times. In the hill lands of central Europe, a road along the valley floor provides the focus, and long-lots reach back from the road to the adjacent ridge crests.

Thinking Geographically

Question 8.39

uxRQQBVFrM9WJ2RbZiKVDRWcMXqOnf70/RhETuOwzMicZMisqqPDSAiK5PFEQhwP3Pl66HZjjBTVoLT0RsiZdFvTUpNTdXXzSome unit-block farms have irregular shapes rather than the rectangular or long-lot patterns. Most of these result from metes and bounds surveying, which makes much use of natural features such as trees, boulders, and streams. Parts of the eastern United States were surveyed under the metes and bounds system, with the result that farms there are much less regular in outline than those where rectangular surveying was used (Figure 8.34).

Thinking Geographically

Question 8.40

PFHiPl7JHlFGpvx9Rs2DjUDHGvbmpNQhFIrQpuICbcbcgLWyLvBw7dyVy2RHT+RD4IT6UiFH0dAa/wjSUoWlgMdiQlHsvEv1BjoZMOy++acGwmlOExO7PEX1yNfyBCmW0QkxXQ==Fencing and Hedging

Fencing and Hedging

Property and field borders are often marked by fences or hedges, heightening the visibility of these lines in the agricultural landscape. Open-field areas, where the dominance of crop raising and the careful tending of livestock make fences unnecessary, still prevail in much of western Europe, India, Japan, and some other parts of the Eastern Hemisphere, but much of the remainder of the world’s agricultural land is enclosed.

Fences and hedges add a distinctive touch to the cultural landscape (Figure 8.35). Different cultures have their own methods and ways of enclosing land, so types of fences and hedges can be linked to particular groups. Fences in different parts of the world are made of substances as diverse as steel wire, logs, poles, split rails, brush, rock, and earth. Those who visit rural New England, western Ireland, or the Yucatán Peninsula will see mile upon mile of stone fence that typifies those landscapes. Barbed-wire fences swept across the American countryside a century ago, but remnants of older styles can still be seen. In Appalachia, the traditional split-rail zigzag fence of pioneer times survives here and there. As do most visible features of culture, fence types can serve as indicators of cultural diffusion.

Thinking Geographically

Question 8.41

fq7ST25RLZE5j3sxpG5m7AK4Ea2Kl0WabiOlweX+cgogjHt4LTsD6E2zlWErISWNQu8Zz00UOIivP5giS4FlfDY21tnk4qwAeXJUocF3WaSepz+R50DStQ==The hedge is a living fence. In Brittany and Normandy in France and in large areas of Great Britain and Ireland, hedgerows are a major aspect of the rural landscape. To walk or drive the roads of hedgerow country is to experience a unique feeling of confinement quite different from the openness of barbed wire or unenclosed landscapes.

245

246