Industrial-Economic Ecology

Industrial-Economic Ecology

How do economic activities affect the natural environment? Industrialization is a process that transforms natural resources into commodities for human use. The theme of cultural ecology, then, is central to understanding industrialization and economic development.

Renewable Resource Crises

Renewable Resource Crises

renewable resource A resource that can be replenished naturally at a rate sufficient to balance its depletion by human use.

At first glance, it might seem that only finite resources are affected by industrialization, but even renewable resources such as forests and fisheries are endangered. The term renewable resources refers to those that can be replenished naturally at a rate sufficient to balance their depletion by human use. That balance is often critically disrupted by the effects of industrialization. So while deforestation is an ongoing process that began at least 3000 years ago, the industrial revolution drastically increased the magnitude of the problem. In just the last half-century, a third of the world’s forest cover has been lost. Today, we witness the rapid destruction of one of the last surviving great woodland ecosystems, the tropical rain forest (Figure 9.11). The most intensive rain-forest clearing is occurring in the East Indies and Brazil, and commercial lumber interests are largely responsible (Figure 9.12). Although trees are a renewable resource when properly managed, too many countries are in effect mining their forests. Foreign rather than Brazilian interests now hold logging rights to nearly 30 million acres (12 million hectares) of Amazonian rain forest. Even when forests are converted into scientifically managed “tree farms,” as is true in most of the developed world, ecosystems often are destroyed. Natural ecosystems have plant and animal diversity that cannot be sustained under the monoculture of commercial forestry.

Thinking Geographically

Question 9.12

Q1A4G9CaiECD3Tn/go9xw1efzMYw0l2PO8Kql3f78IbCsoblzEA81NVT33AUvo+RK1W4ARbTES5QSR8KI34tmw==

Thinking Geographically

Question 9.13

eSH5maq8v6v38ZyYmtWk+sopLyJyorc58cVts0Vc3MdXBM1JhfjOfBPI3s3EDB/j+zZaFpSFlhkoJ4gSSimilarly, overfishing has brought a crisis to many ocean fisheries, a problem compounded by the pollution of many of the world’s seas. The total fish catch of all countries combined rose from 84 million metric tons in 1984 to more than 101 million metric tons by 2009, causing some species to decline. Salmon in Pacific coastal North America and cod in the Maritime Provinces of Canada can be said to have reached a marine biological crisis.

262

Overfishing is a global problem, with some estimates suggesting that if current levels of fishing continue, world fish stocks may be in a total state of collapse by 2048. However, some experts refute these projections, stating that natural dips in fish production always occur and that remaining fish stocks are often underestimated due to difficulties in collecting accurate data. Despite these debates, most experts do agree that fisheries need close oversight to prevent the complete depletion of stocks in areas where fishing is already at or near sustainable levels. Some good news reported in 2009 in the North Sea: for the first time in over a decade, the size of the spawning stock of cod reached a level that scientists agreed was sustainable. Experts credited an array of conservation techniques for the turnaround.

Acid Rain

Acid Rain

acid rain Rainfall with much higher acidity than normal, caused by sulfur and nitrogen oxides derived from the burning of fossil fuels being flushed from the atmosphere by precipitation, with lethal effects for many plants and animals.

Secondary and service industries pollute the air, water, and land with chemicals and other toxic substances. The burning of fossil fuels by power plants, factories, and automobiles releases acidic sulfur oxides and nitrogen oxides into the air; these chemicals are then flushed from the atmosphere by precipitation. The resultant rainfall, called acid rain, has a much higher acidity than normal rain. Overall, 84 percent of U.S. human-produced energy is generated by burning fossil fuels, making acid rain a prevalent phenomenon.

Acid rain can poison fish, damage plants, and diminish soil fertility. Such problems have been studied intensively in Germany, one of the most completely industrialized nations in the world. German scholars have been alarmed by the dramatic suddenness with which the effects of acid rain arrived. In 1982, only 8 percent of forests in western Germany showed damage, but by 1990 the proportion had risen to more than half. In North America, the effects of acid rain have accumulated, but not yet with the speed seen in central Europe. By 1980, more than 90 lakes in the seemingly pristine Adirondack Mountains of New York were dead, meaning devoid of fish life, and 50,000 lakes in eastern Canada faced a similar fate.

263

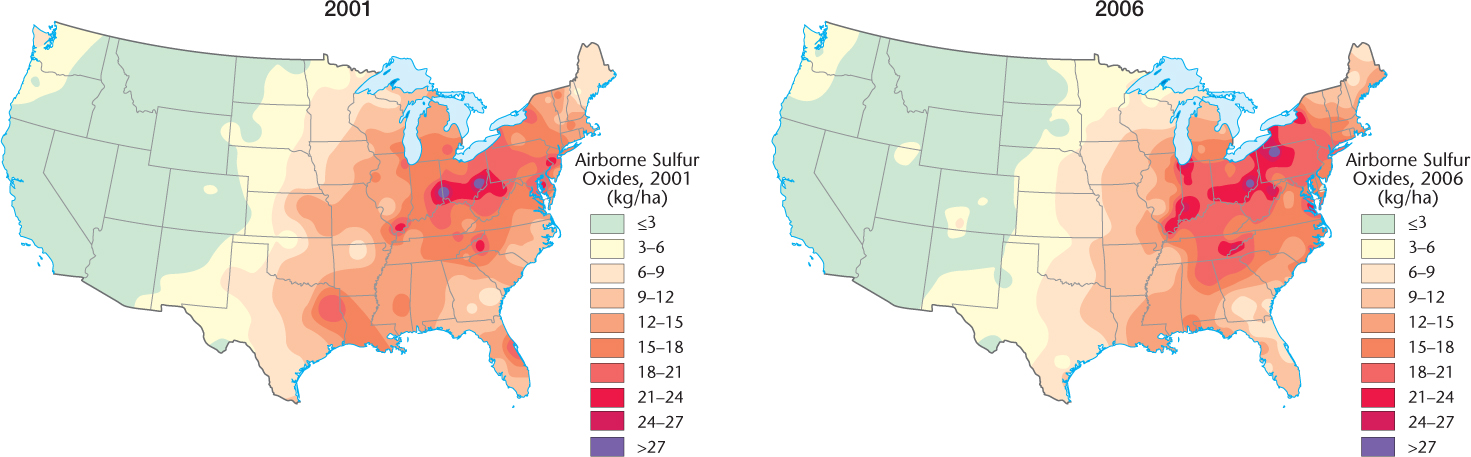

Since about 1990, the acid-rain problem has become less severe in many parts of the world, especially Europe, but the situation in the Adirondacks did not start improving until very recently. For years, the government of Canada urged U.S. officials to take stringent action to help alleviate acid-rain damage, because much of the problem on the Canadian side of the border derives from American pollution. These pleas have begun to have some effect, as new and cleaner technologies for burning fossil fuels have been adopted by companies within the United States. You can see from Figure 9.13 that there is a decrease in acid-rain concentrations in some areas, particularly Louisiana and Illinois. Scientists continue to monitor the situation in order to assess future scenarios.

Thinking Geographically

Question 9.14

39rRvSmru7CKg1o5jcM2e02SI6MVsGY0NeXDU3AKvohGSUvJWhCXvhl+u480L0jTTVXUaol83vW3B39PxRrQIlx6l+HcIZx5VlCTlHFtKiuchalsGlobal Climate Change

Global Climate Change

global warming The pronounced climatic warming of Earth that has occurred since about 1920 and particularly since the 1970s.

Most scientists now agree that we have entered a phase of global warming caused by industrial activity and most particularly by the greatly increased amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) produced by burning fossil fuels. Fossil fuels—coal, petroleum, and natural gas—are burned to produce the energy that powers the world’s factories, and as that burning has increased, so has the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) released into the atmosphere. The 10 hottest years on record have all occurred in the period from 1998 to 2010, based on records compiled at more than 14,000 locations.

Climate change has also contributed to the shrinking of the world’s glaciers. In 2010, a huge ice mass four times the size of Manhattan (the largest in half a century) broke off from the Petermann Glacier in northern Greenland to drift across the Arctic Ocean and threaten oil platforms and shipping lanes. In 2011, a 19-mile crack formed in the Pine Island Glacier in Antarctica, which will soon cause an even larger ice mass measuring 300 to 350 square miles (up to 900 square kilometers) to break off from the continent. This will be the largest ice mass known to have cleaved from a glacier, and it will form the world’s largest iceberg. These are just two examples of the observed shrinking of the world’s glaciers; experts predict further dramatic disappearance of much of the world’s ice in coming years, causing widespread climatic effects. For example, scientists expect that rapidly retreating Arctic ice will leave the Arctic Ocean ice free in summers as soon as the middle of this century.

greenhouse effect A process by which thermal radiation from a planet’s surface is absorbed by atmospheric greenhouse gases, and is reradiated in all directions. Because part of this reradiation is back toward the planet’s surface and the planet’s lower atmosphere, the result is an elevation of the planet’s average surface temperature above what it would be in the absence of the gases. Earth’s natural greenhouse effect makes life as we know it possible. However, human activities, primarily the burning of fossil fuels and clearing of forests, have intensified the natural greenhouse effect, causing global warming.

At issue is the so-called greenhouse effect, a natural process in which thermal radiation from Earth’s surface is absorbed by greenhouse gases and is reradiated in all directions. Because part of this reradiation is back toward Earth’s surface and lower atmosphere, the result is an elevation of Earth’s average surface temperature above what it would be in the absence of the gases. Earth’s natural greenhouse effect makes life as we know it possible. However, human activities, primarily the burning of fossil fuels and clearing of forests, have intensified the natural greenhouse effect. By some estimates, the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide has climbed to the highest level in 180,000 years. In addition, the ongoing destruction of the world’s rain forests adds huge amounts of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere. Although carbon dioxide is a natural component of Earth’s atmosphere, the addition of such huge amounts of the gas is altering the air’s chemical composition. Carbon dioxide, only one of the absorbing gases involved in the greenhouse effect, permits solar short-wave heat radiation to reach Earth’s surface but acts to block or trap long-wave outgoing radiation, causing a thermal imbalance and global heating.

264

As the greenhouse effect warms the global climate and melts or partially melts the polar ice caps, sea levels will continue to rise and the world’s coastlines may soon be inundated. To address this looming crisis, 38 industrialized countries signed the Kyoto Protocol in 2001, agreeing to reduce their emissions of greenhouse gases over a 10-year period. However, the protocol did not impose emissions restrictions on developing countries such as China, Brazil, and India. (These and other developing states have emitted significant amounts of greenhouse gases in recent decades.) Because of these imbalances in emissions restrictions, the United States declined to participate in the Kyoto agreement.

Delegates from over 190 nations met in Doha, Qatar, in late 2012 to ratify an extension of the agreement. However, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, and Russia renounced their obligations under the original agreement. Despite this decreased backing by leading world economic powers, the Doha session ended with the establishment of a second round of environmental commitments for 37 nations. Discussions of a new global pact addressing emissions goals are planned for 2015, and the ensuing agreement will be implemented in 2020, when the Kyoto agreement once again expires.

Overall, environmentalists have been unimpressed by the outcomes of both the Kyoto and the Doha talks. They argue that the talks have not delivered increased cuts in emissions and have not provided feasible ways for the world’s poorest countries to finance their environmental commitments. Instead, under the agreement, developed nations are encouraged to help poorer countries cut emissions and adapt to climate change, but many less-developed countries complain that more affluent nations have been reluctant to deliver this aid. Choosing to pursue its climate-related goals independently, the United States has managed to reduce its emissions of greenhouse gases in recent years, but it has accomplished this goal largely as a result of the decreased industrial activity resulting from the 2008 recession.

Ozone Depletion

Ozone Depletion

Potentially even more serious than the greenhouse effect is the depletion of the upper-atmosphere ozone layer, which acts to shield humans and all other forms of life from the most harmful types of solar radiation. Several chemicals, including the Freon used in refrigeration and air conditioning systems, are almost certainly the main culprits. Refrigeration systems are heavily used in manufacturing plants and are critical for global trade in foods. Because of particular stratospheric conditions, the ozone layer has been most depleted in the Arctic and Antarctic regions. The ozone decrease in the Arctic was first noticed in the early 1990s, with the observation of an ozone hole in that region comparable to the one first detected in the Antarctic during the 1980s. In September 2006, the hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica was the largest ever measured, both in terms of surface area and in the actual loss of mass. In years since, ozone levels in the region have fluctuated but have shown some hopeful signs of a slight recovery.

Other world regions are also affected by the reduction in the ozone layer. In the middle latitudes, where most of the world’s population lives, ozone levels have dropped an average of 5 percent per decade since 1979.

Most of the world’s industrialized countries disperse large amounts of ozone-depleting chemicals into the air. In a plan to mitigate the resulting damage to the ozone layer, many of these states signed the Montreal Protocol in 1989, which was aimed at reducing ozone-damaging substances. The problem is that there is a significant time lag between when these substances are released into the atmosphere and when they are finally dissipated. Recent measurements show a significant reduction in the level of damaging substances within the lower atmosphere but not yet in the higher atmosphere. Scientific estimates suggest that it will take at least another 50 to 75 years for the ozone layer to recover.

Reflecting on Geography

Question 9.15

2HwwvlP3GLxVRSnWA02V9d09SzeaV0uNjFEtzQ4YSBNmkmHEFx6A3hs7dfJ6CtAmDJ1EzqxV1YSzFmrwtx+DDjYI+qyLnKAJ/1QogA8oGwMvml8/C2PVT/rMRCdO5Hyh4B1kipkhkVEuSaaKo0kgseQA8v/gPK7v7LUuSBSpA1EzzgyJRCSMNd0kudNuGesntbq175+R/85oQG8VfutpTw60FlrPLJdVDfakubsytnfvPDp1TySVYXj6X7JR77sM54kgYBmZHlH54JLAA6SiYz5D2ovamvClP7JTO3ESNUzCfhPZtzwn1c7dBu8=Radioactive Pollution

Radioactive Pollution

Like acid rain, radioactive pollution is invisible. It comes from nuclear power plants and waste storage facilities, both consequences of the growing need for energy on the part of industrialized societies. The catastrophe at Chernobyl in Ukraine on April 26, 1986, clearly demonstrated the inherent dangers in reliance on nuclear power. When the Chernobyl nuclear reactor core melted down, causing two explosions, a sizable area around Chernobyl in Ukraine and Belarus became heavily contaminated with deadly radiation; everyone within an 18-mile (30 kilometers) radius of the destroyed reactor had to be evacuated (Figure 9.14). This area remains uninhabited today, save for a few elderly people who refused to leave. Beyond this zone, sizable swaths across Europe were bombarded with various long-lasting radioactive chemicals that attack the entire human body. Some estimates place the amount of radioactive chemicals released as equivalent to at least 750 Hiroshima atomic bombs. Ultimately, a sizable part of both Ukraine and Belarus may be declared unfit for human habitation, and additional tens of thousands of people could die of exposure to radiation caused by this single catastrophe. Another radioactive contaminant released by the explosion continues to leak into the groundwater table at Chernobyl.

Thinking Geographically

Question 9.16

tezYEyTj65ElYIR/mbeigjFfXPHhNQbObL6kMNAicsqC5i6VAz9s+xbpMhos5WuL6marGwdnP0xztiR60ZaUlucbrE3ZLQvKt7biuQYVPGQtxqVy70J2Sy8tr4qkwsj+aiLnuw==265

More recently, an accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Plant in northeastern Japan caused radioactive pollution to be released after a 2011 earthquake and tsunami. Experts estimate this to be about one-tenth the magnitude of the Chernobyl disaster in terms of its environmental impact. Nevertheless, a 12- to-19-mile (20- to 30-kilometer) radius around the plant was declared an “exclusion zone” following the disaster. This zone may be uninhabitable and unsafe to farm for many decades to come. The ominous term national sacrifice area has been used by government officials as a euphemism to describe such districts that have been rendered permanently uninhabitable by radiation pollution. Geographers often refer to such areas as hazardscapes. Outside the immediate exclusion zone created by the Fukushima disaster, unsafe levels of radioactive pollution have been detected in the Japanese food supply and in the country’s water supplies. Thus far, only trace amounts of radioactive pollution from Fukushima appear to have been carried through the air and water to other countries such as the United States and Canada. However, large amounts of radioactive isotopes were released into the Pacific Ocean during the disaster, and impact on marine life and other ocean resources is not yet known.

266

Environmental Sustainability

Environmental Sustainability

sustainability The survival of a land-use system for centuries or millennia without destruction of the environmental base.

The key issue in all these industry-related ecological problems is sustainability. A sustainable environment is defined as one that would last for centuries or millennia, providing adequate resources for the population without destruction of the environmental base. Can our present industry-based way of life continue without causing those resources to run out, leading to ecological collapse?

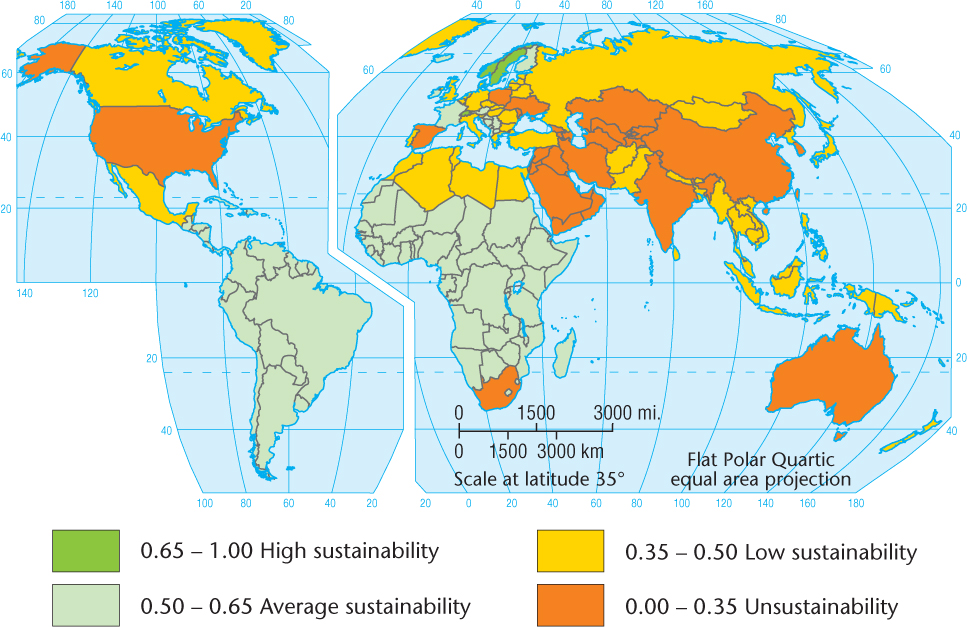

The Environmental Sustainability Index (ESI) has been devised to measure, country by country, the level of progress toward sustainability. The highest possible score on the ESI is 1.00, the lowest 0.00. Eleven major indicators of environmental sustainability, including carbon dioxide emissions, water quality, and biodiversity, are included in each country’s score (Figure 9.15). In 2011, the highest ranked country was Norway, at 0.8232; the lowest was India at 0.2396. Although far from being a perfect measure, the ESI clearly points to regions where ecosystems are most highly stressed. These regions lie mainly in Asia but also include the United States, Australia, and parts of Europe.

Environmental Sustainability Index (ESI)

Thinking Geographically

Question 9.17

DMEOV/mS8L6pp76PXykcfBeV/KiIT6g8wHHZrj6TcZ2ZQjhiClLblhsxatw+2Ankc2H0BTAxAGn5lVKUDeveloping new sources of energy is one of the keys to environmental sustainability. For example, notable progress is being made in the use of wind power to generate electricity. In the United States alone, wind power produced over 94,000 megawatts of electricity by the end of 2010, about 2.3 percent of the total generated. However, the United States still lags far behind such countries as Denmark, Spain, and Germany. Texas, Iowa, Minnesota, and Illinois are the leading wind-power states.

ecotourism Responsible travel that does not harm ecosystems or the well-being of local people.

Another development fostering sustainability is ecotourism, defined as responsible travel that does not harm ecosystems or the well-being of local people.

Ecotourism arose when it was recognized that even seemingly benign industries such as tourism can create ecological problems. Ecotourists tend to visit out-of-the-way places with exotic, healthy ecosystems. They disdain the comforts of large hotels and resorts, preferring more spartan conditions. Revenue from ecotourism is helping to rescue Uganda’s mountain gorillas from extinction, especially now that the government has realized that the wildlife serves as a valuable tourist attraction.

Greens Activists and organizations, including political parties, whose central concern is addressing environmental issues.

Also notable has been the rise of the Greens, political activists who advocate an emphasis on environmental issues. Many countries now have Green political parties. Also active in environmental advocacy are groups such as the Sierra Club, Greenpeace, and the Nature Conservancy.

267