1-2 Perspectives on Brain and Behavior

Back to our central topic, how the study of brain and behavior are related. Many philosophers have reasoned about the causes of behavior. Their speculations can be classified into three broad approaches: mentalism, dualism, and materialism. After describing each, we explain why contemporary brain investigators subscribe to the materialist view. In reviewing these theories, you will recognize that some familiar “commonsense” ideas about behavior derive from these long-

Aristotle and Mentalism

7

The hypothesis that the mind (or soul or psyche) controls behavior can be traced back more than 2000 years to ancient Greece. In classical mythology, Psyche, a mortal, became the wife of the young god Cupid. Venus, Cupid’s mother, opposed his marriage, so she harassed Psyche with almost impossible tasks.

Psyche performed the tasks with such dedication, intelligence, and compassion that she was made immortal, thus removing Venus’s objection to her. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle was alluding to this story when he suggested that all human intellectual functions are produced by a person’s psyche. The psyche, Aristotle argued, is responsible for life, and its departure from the body results in death.

Aristotle’s account of behavior marks the beginning of modern psychology, but the brain played no role in it. Aristotle thought the brain existed to cool the blood. Even if he had thought that the brain ruled behavior, as did some other philosophers and physicians of his time, it would have made little difference in the absence of any idea of how a body organ could produce behavior (Gross, 1995).

To Aristotle, the psyche was responsible for human consciousness, perceptions, and emotions and for such processes as imagination, opinion, desire, pleasure, pain, memory, and reason. The nonmaterial psyche was an entity independent of the body. In formulating the concept of a soul, Christianity adopted Aristotle’s view that a nonmaterial entity governs our behavior and that our essential consciousness survives our death.

Mind is an Anglo-

Descartes and Dualism

In the first book on brain and behavior, René Descartes (1664), a French philosopher, proposed a new explanation of behavior in which he retained the mind’s prominence but gave the brain an important role. Descartes placed the seat of the mind in the brain and linked the mind to the body. He stated in the first sentence of Treatise on Man (1664) that mind and body “must be joined and united to constitute people.”

Descartes’s innovation was the insight into how body organs produce their actions. He realized that mechanical and physical principles could explain most activities of body and brain—

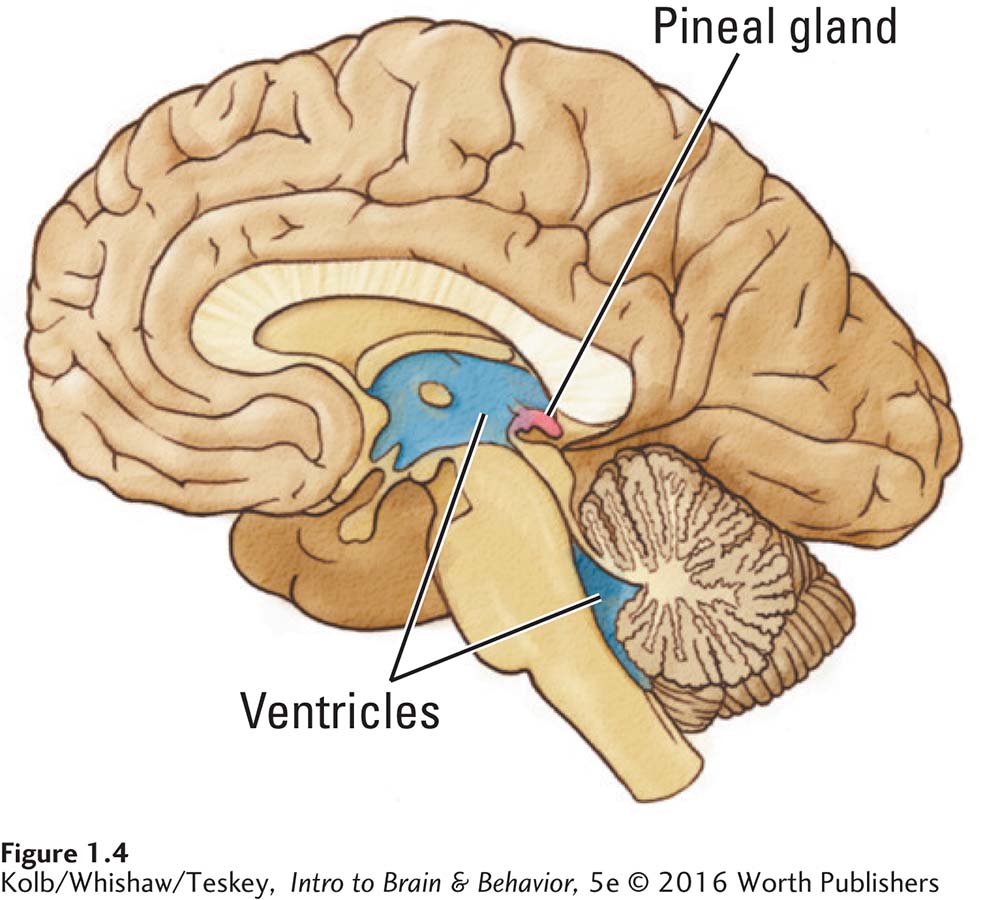

But Descartes could not imagine how consciousness could be reduced to a mechanistic explanation. He thus retained the idea that a nonmaterial mind governs rational behavior. Descartes did, however, develop a mechanical explanation for how the mind interacts with the body to produce movement, working through a small structure at the brain’s center, the pineal body (pineal gland). He concluded that the mind instructed the pineal body, which lies beside fluid-

8

Descartes’s thesis that the mind directed the body was a serious attempt to give the brain an understandable role in controlling behavior. This idea that behavior is controlled by two entities, a mind and a body, is dualism (from Latin, meaning two). To Descartes, the mind received information from the body through the brain. The mind also directed the body through the brain. The rational mind, then, depended on the brain both for information and to control behavior.

Problems plague Descartes’s dualistic theory. It quickly became apparent to scientists that people who have a damaged pineal body or even no pineal body still display typical intelligent behavior. Today, we understand that the pineal gland’s role in behavior is relegated to biological rhythms; it does not govern human behavior. We now know that fluid is not pumped from the brain into muscles when they contract. Placing an arm in a bucket of water and contracting its muscles does not cause the water level in the bucket to rise, as it should if the volume of the muscle increased because fluid had been pumped into it. We now also know that there is no obvious way for a nonmaterial entity to influence the body: doing so requires the spontaneous generation of energy, which violates the physical law of conservation of matter and energy.

The difficulty in Descartes’s theory of how a nonmaterial mind and a physical brain might interact has come to be called the mind–

A 2014 film, The Imitation Game, dramatizes Turing’s efforts during World War II to crack the Nazi’s Enigma code.

The contemporary version of Descartes’ language test, the Turing test, is named for Alan Turing, an English mathematician. In 1950, Turing proposed that a machine could be judged conscious if a questioner could not distinguish its answers from a human’s. Machines are close to passing the Turing test; some might argue that it’s happened. Experimental research also casts doubt on Descartes’s view that nonhuman animals cannot pass the language and action tests. Studies of language in apes and other animals partly seek to discover whether other species can describe and reason about things that are not present. Comparative Focus 1-2, The Speaking Brain, summarizes a contemporary approach to studying language in animals.

Descartes’s theory of mind led to bad results. Based on dualism, some people argued that young children and the insane must lack minds, because they often fail to reason appropriately. We still use the expression he’s lost his mind to describe someone who is mentally ill. Some proponents of dualism also reasoned that, if someone lacked a mind, that person was simply a machine, not due respect or kindness. Cruel treatment of animals, children, and the mentally ill has for centuries been justified by Descartes’s theory. It is unlikely that Descartes himself intended these interpretations. Reportedly he was very kind to his own dog, Monsieur Grat.

Darwin and Materialism

By the mid-

9

COMPARATIVE FOCUS 1-2

The Speaking Brain

Language is such a striking characteristic of our species that it was once thought unique to humans. Yet evolutionary theory finds it unlikely that language appeared full-

In language studies with chimpanzees, humans’ closest living relatives, scientists have used two approaches: language training and analyzing spontaneous vocalizations and gestures (Gillespie-

Malatta’s son Kanzi accompanied his mother to class and became an excellent Yerkish student. Kanzi also displayed clear evidence of understanding complex human speech. While recording his vocalizations when interacting with people and eating, Jared Taglialatela and coworkers found that Kanzi made many sounds associated with their meanings, or semantic context. For example, Kanzi associated various peeps with specific foods. The research group also found that chimps use a raspberry or extended grunt sound in a specific context to attract the attention of others, including people.

Imaging brain blood flow associated with the use of chimpanzeeish indicates that humans and chimpanzees activate the same brain regions when they speak (Taglialatela, 2011). Wild bonobos are found to use one distinct call to attract others to feeding locations and another to initiate a trip. The animals also use numerous gestures to signal intent to others.

Stewart Watson and colleagues (2015) report that in two chimpanzee colonies, the animals used different referential calls (names) for apples. When the groups were combined, both modified their calls and adopted a common call, an example of gestural drift analogous to people adopting the speech patterns of those around them. The study demonstrates that chimpanzees can learn and share referential calls.

Evolution by Natural Selection

Wallace and Darwin independently arrived at the same conclusion—

Both Darwin and Wallace had looked carefully at the anatomy of animals and at animal behavior. Both were struck by the myriad characteristics common to so many species despite their diversity. For example, the skeleton, muscles, and body parts of humans, monkeys, and other mammals are remarkably similar. So is their behavior: many animal species reach for food with their forelimbs.

Such observations led first to the idea that living organisms must be related, an idea widely held even before Wallace and Darwin. More important, these same observations led Darwin to explain how the great diversity in the biological world could have evolved from common ancestry. Darwin proposed that animals have traits in common because these traits are passed from parents to their offspring.

Natural selection is Darwin’s theory for explaining how new species evolve and how existing species change over time. A species is a group of organisms that can breed among themselves. Individual organisms of any species vary extensively in their phenotype, the characteristics we can see or measure. No two individuals of any species are exactly alike. Some are big, some are small, some are fat, some are fast, some are light-

Figure 2-1 illustrates this principle of phenotypic plasticity.

10

Individual organisms whose characteristics best help them to survive in their environment are likely to leave more offspring than are less-

Natural Selection and Heritable Factors

Neither Darwin nor Wallace understood the basis of the great variation in plant and animal species they observed. Another scientist, the monk Gregor Mendel, discovered one principle underlying phenotypic variation and how traits pass from parents to their offspring. Through experiments he conducted on pea plants in his monastery garden beginning about 1857, Mendel deduced that heritable factors, which we now call genes, govern various physical traits displayed by the species.

Section 3-3 explains what constitutes a gene, how genes function, and how genes can change, or mutate.

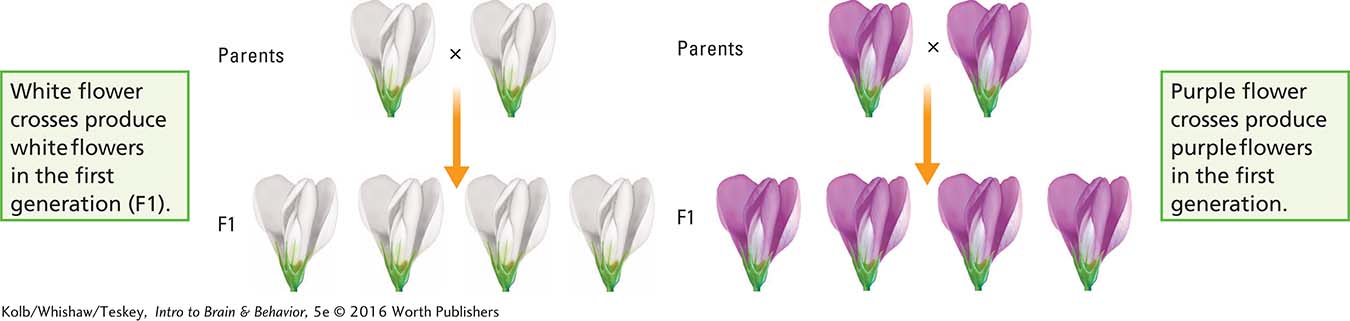

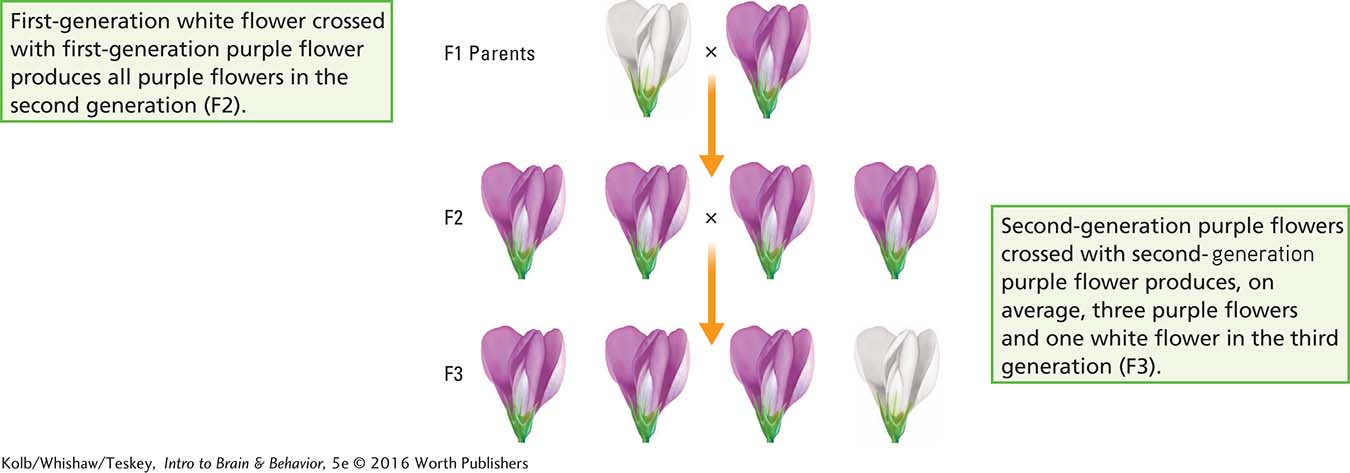

Members of a species that have a particular genetic makeup, or genotype, are likely to express (turn on) similar phenotypic traits, as posited in the Procedure section of Experiment 1-1. If the gene or combination of genes for a trait, say, flower color, is passed on to offspring, the offspring will express the same trait, as illustrated at the top of the Results section in Experiment 1-1. Two white-

11

EXPERIMENT 1-1

Question: How do parents transmit heritable factors to offspring?

Procedure

Mendel crossbred pea plants, then observed which traits parent plants passed to their offspring in successive generations.

Results

Conclusion: An individual inherits two factors (genes) for each trait, but the effects of one gene may hide the other gene in the individual. The hidden gene can resurface after crossbreeding.

Mendel then experimented with crossbreeding F1 purple and white pea plant flowers. The illustration at the bottom of the Results section in Experiment 1-1 shows that second-

This result suggested to Mendel that the trait for white flowers had not disappeared but rather was hidden by the trait for purple flowers. He concluded that individuals inherit two factors, or genes, for each trait, but one may dominate and hide (suppress) the other in the individual’s phenotype.

Thus, the unequal ability of individual organisms to survive and reproduce is related to the different genes they inherit from their parents and pass on to their offspring. By the same token, similar characteristics within or between species are usually due to similar genes. For instance, genes that produce the nervous system in different animal species tend to be very similar.

Interplay of Genes, Environment, and Experience

The principles of inheritance that Mendel demonstrated through his experiments have led to countless discoveries about genetics. We now know that new traits appear because new gene combinations are inherited from parents, existing genes change or mutate, suppressed genes are re-

But genes alone cannot explain most inherited traits. Mendel realized that environment participates in expression of traits: planting tall peas in poor soil reduces their height, for example. Experience likewise plays a part. The experience of children who attend a substandard school, for example, is far different from that of children who attend a model school.

Consult Section 3-3 for details on genetic and epigenetic principles.

Epigenetics is the study of differences in gene expression related to environment and experience. Epigenetic factors do not change your genes, but they do influence how your genes express the traits you’ve inherited from your parents. Epigenetic changes can persist throughout a lifetime, and their cumulative effects can make dramatic differences in how your genes work. Epigenetic factors described throughout this book are revolutionizing our understanding of gene–

Summarizing Materialism

Darwin’s theory of natural selection, Mendel’s discovery of genetic inheritance, and the reality of epigenetics have three important implications for studying the brain and behavior:

Section 3-1 describes the varieties of neurons and other brain cells.

Because all animal species are related, their brains must be related. A large body of research confirms first that all animals’ brain cells are so similar that these cells must be related and second that all animal brains are so similar that they must be related as well. Brain researchers study the nervous systems of animals as different as slugs, fruit flies, rats, and monkeys, knowing that they can extend their findings to the human nervous system.

More on emotions and their expression in Sections 12-2, 12-4, and 14-3.

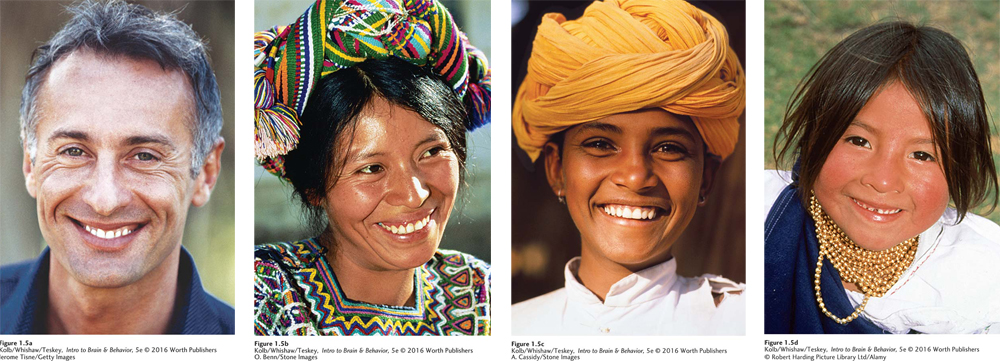

Because all animal species are related, their behavior must be related. In his book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, Darwin (1872) argued that emotional expressions are similar in humans and other animals because we inherited them from a common ancestor. Figure 1-5 offers evidence. That people the world over display the same behavior suggests that the trait is inherited rather than learned.

Figure 1-5: FIGURE 1-

Figure 1-5: FIGURE 1-5 An Inherited Behavior People the world over display the same emotional expressions that they recognize in others— these smiles, for example. This evidence supports Darwin’s suggestion that emotional expression is an inherited behavior. © Robert Harding Picture Library Ltd/Alamy12

Brain and behavior in complex animals such as humans evolved from simpler animals’ brains and behaviors and also depend on learning. Coming up in Section 1-3 we trace the evolution of nervous systems and their increasingly complex repertoires of actions, from a simple netlike arrangement to a multipart nervous system with a brain that controls behavior.

Contemporary Perspectives on Brain and Behavior

Where do modern students of the brain stand on the perspectives of mentalism, dualism, and materialism? In his influential 1949 book, The Organization of Behavior, psychologist Donald O. Hebb describes the scientific acceptance of materialism in a folksy manner:

Modern psychology takes completely for granted that behavior and neural function are perfectly correlated, that one is completely caused by the other. There is no separate soul or life force to stick a finger into the brain now and then and make neural cells do what they would not otherwise. (Hebb, 1949, p. iii)

Hebb’s claim dovetails with his theory of how the brain produces consciousness. He suggested that learning is enabled by neurons forming new connections with one another in the brain. He called the resulting neuronal network a cell assembly. As the neural substrate for the learned experience, cell assemblies interact: one cell assembly becomes connected to another. This linking of cell assemblies is thus the linking of memories, which to Hebb is what consciousness is.

Hebb’s argument is materialistic. The contemporary philosophical school eliminative materialism takes the position that if behavior can be described adequately without recourse to the mind, then the mental explanation should be eliminated. Daniel Dennett (1978) and other philosophers, who have considered such mental attributes as consciousness, pain, and attention, argue that an understanding of brain function can replace mental explanations of these attributes. Mentalism, by contrast, defines consciousness as an entity, attribute, or thing. Let us use the concept of consciousness to illustrate the argument for eliminative materialism.

Recovering Consciousness: A Case Study

13

Darwin offered no suggestion about how the brain produces consciousness, although his theory predicted that it must. One patient’s case study offers insight into how the study of brain and behavior begins to describe consciousness. The patient, a 38-

This patient is one of approximately 1.4 million people each year in the United States who, as described by Fred Linge in Clinical Focus 1-1, contend with TBI. Among them, as many as 100,000 may become comatose; as few as 20 percent recover consciousness. Among the remaining TBI patients, some are diagnosed as being in a persistent vegetative state (PVS), alive but unable to communicate or to function independently at even the most basic level. Their brain damage is so extensive that no recovery can be expected. Others, such as the MCS assault victim described earlier, are so diagnosed because behavioral observation and brain imaging studies suggest that they do have a great deal of functional brain tissue remaining.

Adrian Owen (2015) and his colleagues have found that by imaging the brain of comatose patients they can assess the extent to which the patients are conscious by the patterns of activity in their brain. Using an imaging system that measures brain function in terms of oxygen use, Owen’s group discovered that some comatose patients are actually locked in, as was Martin Pistorius, whom you met in Section 1-1.

Furthermore, these investigators devised ways to communicate with conscious patients by teaching them a language that signals changes in their brains’ activity patterns. For example, while imaging the brain of control subjects, Owen’s group asks them to imagine hitting a tennis ball with a racket. The group identifies the active brain region associated with the imaginary act. They then ask patients to imagine hitting a tennis ball and so determine from their brain images whether they understand. If the patient understands the instruction and so demonstrates consciousness, procedures for further communication and rehabilitation can begin.

On the rehabilitation front, Nicholas Schiff and his colleagues (Schiff & Fins, 2007) reasoned that, if they could stimulate their MCS patient’s brain by administering a small electrical current, they could improve his behavioral abilities. As part of a clinical trial (a consensual experiment directed toward developing a treatment), they implanted thin wire electrodes in his brainstem so they could administer a small electrical current.

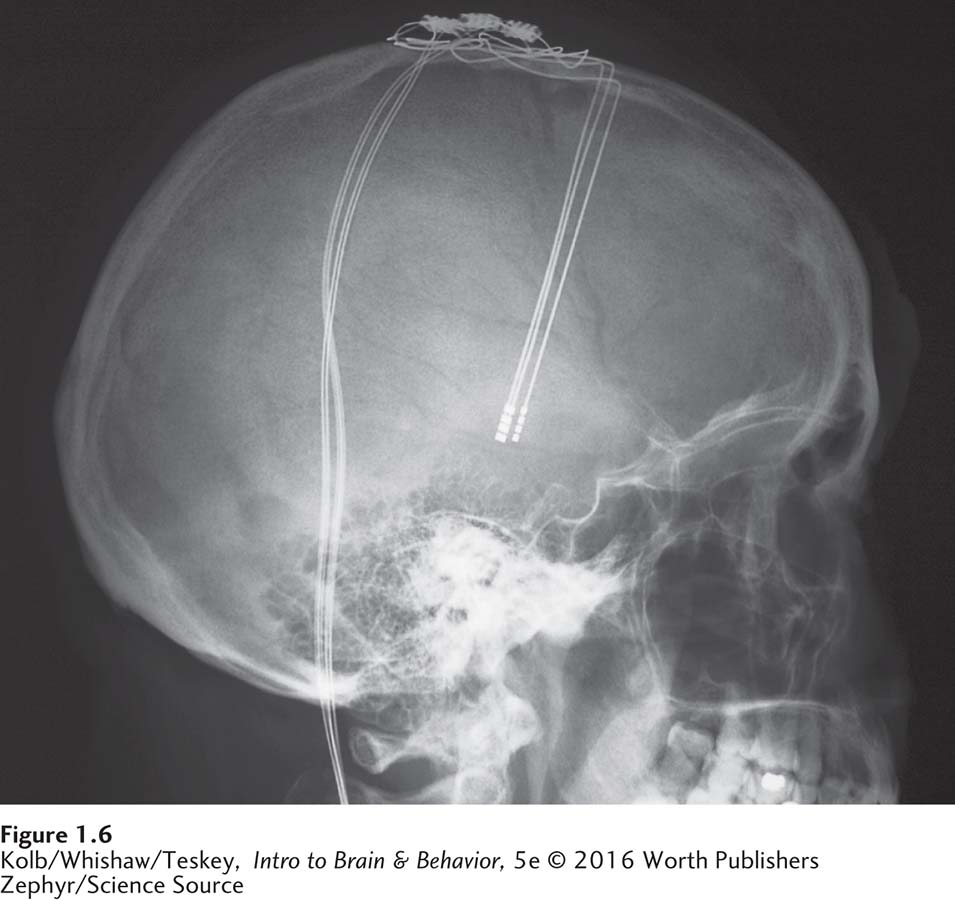

Through these electrodes, which are visible in the X-

The experimenters’ very practical measures of consciousness are formalized by the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), one indicator of the degree of unconsciousness and of recovery from unconsciousness. The GCS rates eye movement, body movement, and speech on a 15-

14

More research on and treatments for MCS and TBI in Sections 7-3, 14-5, and 15-7. Concussion is the topic of Focus 16-3.

People under the age of 19 can be especially vulnerable to head trauma and concussion when they participate in recreational activities and sporting competitions. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has cited bicycling and football injuries as leading causes of TBI in this population. TBI can also lead to accelerated brain aging, an area of growing concern for participants in athletic competitions that lead to repeated concussion or other head trauma, and to military combatants.

The Separate Realms of Science and Belief

Contemporary brain theory is materialistic. Although materialists, your authors included, continue to use subjective mentalistic words such as consciousness, pain, and attention to describe more complex behaviors, at the same time they recognize that these words do not describe mental entities. Materialism argues for objective, measurable descriptions of behavior that can be referenced to brain activity.

Some people may question materialism’s tenet that only the brain is responsible for behavior because they think it denies religion. But materialism is neutral with respect to religion. Many of the world’s major religions accept both evolution and the brain’s centrality in behavior as important scientific theories. Fred Linge, introduced in Clinical Focus 1-1, has strong religious beliefs, as do the other members of his family. They used their religious strength to aid in his recovery. Yet despite their religious beliefs, they realize that Linge’s brain injury caused his changed behavior and that learning to compensate for his impairments caused his brain function to improve.

The four-

Indeed, many behavioral scientists hold religious beliefs and see no contradiction between them and their engagement with science. Science is not a belief system but rather a set of procedures designed to allow investigators to confirm answers to a question independently. As outlined in Experiment 1-1, this four-

1-2 REVIEW

Perspectives on Brain and Behavior

Before you continue, check your understanding.

Question 1

The view that behavior is the product of an intangible entity called the mind (psyche) is __________. The notion that the immaterial mind acts through the material brain to produce language and rational behavior is __________. __________, the view that brain function fully accounts for all behavior, guides contemporary research on the brain and behavior.

Question 2

The implication that the brains and behaviors of complex animals such as humans evolved from the brains and behaviors of simpler animals draws on the theory of __________ advanced by __________.

Question 3

The brain demonstrates a remarkable ability to recover, even after severe brain injury, but an injured person may linger in a __________, occasionally able to communicate or to follow simple commands but otherwise not conscious. Those who have such extensive brain damage that no recovery can be expected remain in a __________, alive but unable to communicate or to function independently at even the most basic level.

Question 4

Darwin and Mendel were nineteenth-

Answers appear in the Self Test section of the book.