14-2 Dissociating Memory Circuits

Beginning in the 1920s and continuing until the early 1950s, American psychologist Karl Lashley searched in vain for the neural circuits underlying memories. Lashley’s working hypothesis was that memories must be represented in the perceptual and motor circuitry used to learn to solve problems. To find that circuitry, he investigated the ways laboratory rats and monkeys learn specific tasks for food reward. He believed that if he removed bits of this circuitry or disconnected it, amnesia should result.

Brain lesions are an ablation technique—

In fact, neither ablation procedure produced amnesia. Lashley found instead that the severity of memory disturbance was related to the size of the lesion rather than to its location. After searching for 30 years, Lashley concluded that he had failed to find the location of a memory trace, although he believed that he knew where it was not located (Lashley, 1960).

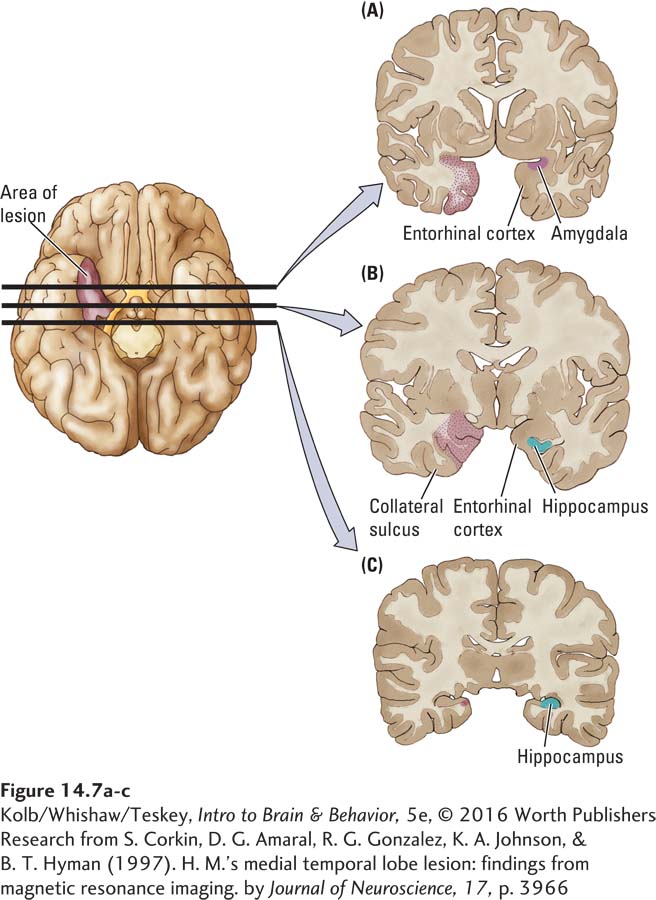

Just two years later, neurosurgeon William Scoville discovered serendipitously what Lashley’s studies had not predicted. Scoville was attempting to rid people of seizures by removing the abnormal brain tissue that caused them. In August 1953, Scoville performed a bilateral medial temporal lobe resection on a young man, Henry Molaison (H. M.), whose severe epilepsy was not controlled by medication. H. M.’s seizures originated in the medial temporal lobe region, so Scoville bilaterally removed much of the hippocampal formation, along with some of the amygdala and adjacent neocortical structures. The procedure left the more lateral temporal lobe tissue intact. As shown in Figure 14-7, removal specifically included the anterior part of the hippocampus, the amygdala, and adjacent cortex.

Disconnecting Explicit Memory

489

The behavioral symptoms Scoville noted after the surgery were completely unexpected. He invited Brenda Milner (Milner et al., 1968) to study H. M. Milner had been studying memory difficulties in patients with unilateral temporal lobe removals for the treatment of epilepsy. She and her colleagues worked with H. M. for more than 50 years, making his the most studied case in neuroscience (e.g., Corkin, 2002). H. M. died in 2008.

His most remarkable symptom was severe amnesia: he was unable to recall anything that had happened since his surgery in 1953. H. M. retained an above-

In one study by Suzanne Corkin (2002), H. M. was given a tray of hospital food, which he ate. A few minutes later, he was given another tray. He did not recall having eaten the first meal and proceeded to eat another. A third tray was brought, and this time he ate only the dessert, explaining that he did not seem to be very hungry.

To understand the implications and severity of H. M.’s condition, one need only consider a few events in his postsurgical life. His father died, but H. M. continued to ask where his father was, only to experience anew the grief of learning that his father had passed away. (Eventually H. M. stopped asking about his father, suggesting that some type of learning had taken place.)

Similarly, in the hospital, he typically asked the nurses, with many apologies, to tell him where he was and how he came to be there. He remarked on one occasion, “Every day is alone in itself, whatever enjoyment I’ve had and whatever sorrow I’ve had.” He perceived his surroundings but could not comprehend his situation because he did not remember what had gone before.

Prosopagnosia, an inability to recognize faces, and other visual form agnosias are topics in Chapter 9.

Formal tests of H. M.’s memory showed, as you would expect, no recall for specific information just presented. In contrast, his implicit memory performance was nearly intact. He performed at normal on tests such as the incomplete figure and pursuit rotor tasks, illustrated in Figures 14-3 and 14-4, respectively. So while his implicit memory system must have been intact, the systems crucial to explicit memory were missing or dysfunctional. Yet H. M. recognized faces, including his own, and he recognized that he aged. Face recognition depends on the parahippocampal gyrus, which was partly intact on H. M.’s right side. Clinical Focus 14-2, Patient Boswell’s Amnesia, describes a case similar to H. M.’s.

Disconnecting Implicit Memory

Among the reasons Lashley’s research did not find a syndrome like that shown by H. M., the two most important are that Lashley did not damage the medial temporal regions. Nor did he use tests of explicit memory, so his animal subjects would not have shown H. M.’s deficits. Rather, Lashley’s tests were mostly measures of implicit memory, with which H. M. had no problems.

The following case illustrates that Lashley probably should have been looking in the basal ganglia for the deficits that his implicit memory tests revealed. The basal ganglia play a central role in motor control. Among the compelling examples of implicit memory is motor learning—

Focus features 5-2, 5-3, and 5-4 and Section 7-1 detail aspects of Parkinson disease. Section 16-3 reviews treatments.

J. K. was above average in intelligence and worked as a petroleum engineer for 45 years. In his mid-

Curiously, his memory disturbance was related to tasks J. K. had performed his whole life. On one occasion, he stood at his bedroom door, frustrated by his inability to recall how to turn on the lights. “I must be crazy,” he remarked. “I’ve done this all my life and now I can’t remember how to do it!” On another occasion, he was seen trying to turn the radio off with the television remote control. This time he explained, “I don’t recall how to turn off the radio so I thought I would try this thing!”

490

CLINICAL FOCUS 14-2

Patient Boswell’s Amnesia

At the age of 48, Boswell developed herpes simplex encephalitis, a brain infection. He had completed 13 years of schooling and had worked for nearly 30 years in newspaper advertising. By all accounts a normal, well-

Boswell recovered from the acute symptoms, including seizures and a 3-

But Boswell was left with a severe amnesic syndrome. If he hears a short paragraph and is asked to describe its main points, he routinely scores zero. He can only guess the day’s date and is unable even to guess the year. When asked what city he is in, he simply guesses.

Boswell does know his place of birth and can correctly recall his birth date about half the time. In sum, Boswell has severe amnesia for events both before and since his encephalitis. Like H. M., he does show implicit memory on tests such as the pursuit rotor task.

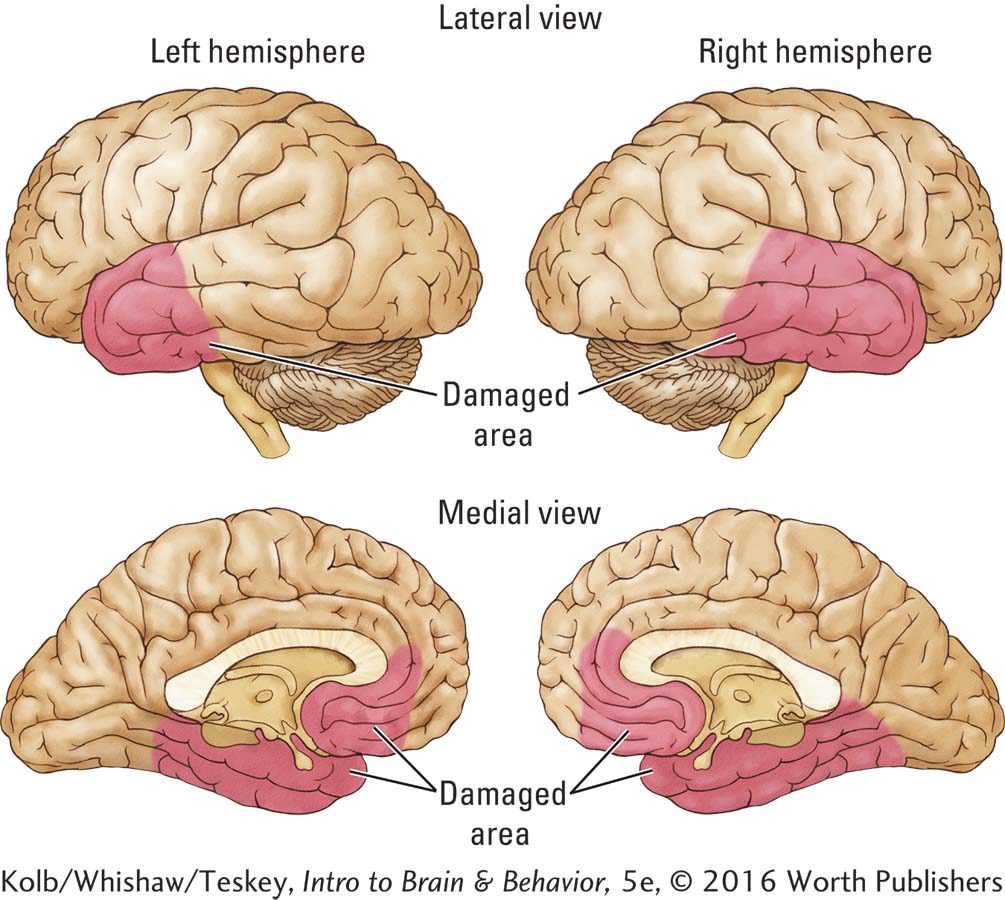

Antonio Damasio and his colleagues (1989) have investigated Boswell’s amnesia extensively, and his brain pathology is now well documented. The critical damage, diagrammed in the adjoining illustration, is bilateral destruction of the medial temporal regions and a loss of the basal forebrain and the posterior part of the orbitofrontal cortex. In addition, Boswell has lost the insular cortex from the lateral fissure (not visible in the illustration).

Boswell’s sensory and motor cortices are intact, as are his basal ganglia, but his injury is more extensive than H. M.’s. Like H. M., he has no new memories. Unlike H. M., he also has a severe loss of access to old information, probably owing to his insular and prefrontal injuries. Nonetheless, again like H. M.’s, Boswell’s procedural memory is intact, illustrating the dissociation between neural circuits underlying explicit and implicit forms of memory.

J. K.’s clear implicit memory deficit contrasts sharply with his awareness of daily events. He recalled explicit events as well as most men his age and spoke intelligently on issues of the day that he had just read about. Once when two of us visited him, one of us entered the room first and he immediately asked where the other was, even though it had been 2 weeks since we told him that we would be coming to visit.

This intact long-

14-2 REVIEW

Dissociating Memory Circuits

Before you continue, check your understanding.

Question 1

Based on the case of H. M., we can conclude that the structures involved in explicit memory include the ____________, the ____________, and adjacent cortex.

Question 2

Implicit memory deficits in patients with Parkinson disease demonstrate that a major structure in implicit memory is the ____________.

Question 3

What is the main difference between the Lashley and Milner studies?

Answers appear in the Self Test section of the book.