Chapter Introduction

561

CHAPTER 16

What Happens When the Brain Misbehaves?

RESEARCH FOCUS 16-

16-1 MULTIDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH ON BRAIN AND BEHAVIORAL DISORDERS

CAUSES OF DISORDERED BEHAVIOR

INVESTIGATING THE NEUROBIOLOGY OF BEHAVIORAL DISORDERS

16-2 CLASSIFYING AND TREATING BRAIN AND BEHAVIORAL DISORDERS

IDENTIFYING AND CLASSIFYING BEHAVIORAL DISORDERS

TREATMENTS FOR DISORDERS

RESEARCH FOCUS 16-

16-3 UNDERSTANDING AND TREATING NEUROLOGICAL DISORDERS

TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY

CLINICAL FOCUS 16-

STROKE

EPILEPSY

MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS

NEURODEGENERATIVE DISORDERS

ARE ALL DEGENERATIVE DEMENTIAS ASPECTS OF A SINGLE DISEASE?

AGE-

16-4 UNDERSTANDING AND TREATING PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS

SCHIZOPHRENIA SPECTRUM AND OTHER PSYCHOTIC DISORDERS

MOOD DISORDERS

RESEARCH FOCUS 16-

ANXIETY DISORDERS

16-5 IS MISBEHAVIOR ALWAYS BAD?

562

RESEARCH FOCUS 16-1

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Life is filled with stress. Routinely, we cope. But some events are so physically threatening and often emotionally shattering that long-

Traumatic events that may trigger PTSD include violent assault, natural or human-

That a beneficial therapy is to relive a traumatic event is counterintuitive. Yet in virtual reality (VR) exposure therapy, a controlled virtual immersion environment combines realistic street scenes, sounds, and odors that allow people to relive traumatic events (Gonçalves et al., 2012). The Virtual Iraq and Afghanistan Simulation is customized for war veterans to start with benign events—

To make Virtual Iraq realistic, the system pumps in smells, stepping up from the scent of bread baking to body odor to the reek of gunpowder and burning rubber. Speakers provide sounds while off-

Many unknowns related to PTSD remain, including how stress injures the brain, especially the frontal lobes and hippocampus (Wingenfeld & Wolf, 2014); why some people do not develop PTSD following extremely stressful events; and the extent to which PTSD is associated with other health events, including previous stressors, diabetes, and head trauma (Costanzo et al., 2014). That said, assessment and treatment options for most of those who endure PTSD are poor: over half of all war veterans, for example, receive no assessment or treatment.

Current understanding of PTSD illustrates how thinking on the brain’s role in health can shift. Largely as a result of symptoms displayed by returning Vietnam War veterans, in 1980 the DSM-

A prominent feature of PTSD diagnosis is that a traumatic external agent, rather than internal causes, is prominent in producing the characteristic set of behavioral symptoms described in Research Focus 16-1, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Neuroscientists now recognize that the brain contributes to PTSD development and that traumatic experiences related to policing, firefighting, and accidental events can contribute to the condition.

The many discussions of behavioral disorders and organic disease presented throughout this book serve both to illustrate the brain’s organization and functioning and to exemplify how knowledge about brain function contributes to understanding and treating brain disorder and disease. Classifying and treating organic and behavioral conditions is our focus in this chapter.

We know that the brain is complex. We do not yet understand all its parts and their functions, nor is it clear how the brain produces mind, a sense of well-

563

To illustrate progress in studying brain and behavior over the past century, we can contrast the theories of Sigmund Freud with present-

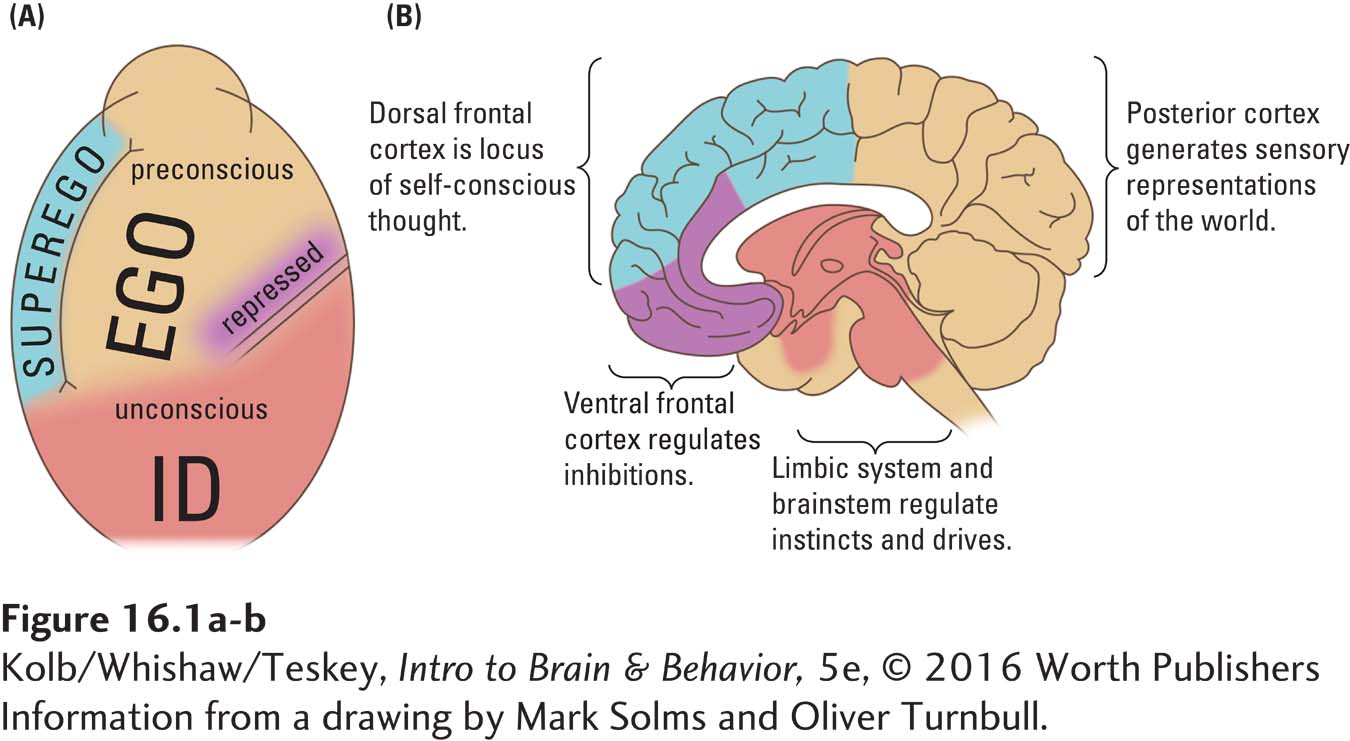

Freud proposed the three components of mind illustrated in Figure 16-1A:

Primitive functions, including the “instinctual drives” of sex and aggression, arise from the id, the part of the mind that Freud thought operated on an unconscious level.

The rational part of the mind he called the ego. Freud also believed, much of the ego’s activity to be unconscious, although experience (to him, perceptions of the world) is conscious.

The superego aspect of mind acts to repress the id and to mediate ongoing interactions between the ego and the id.

For Freudians, abnormal behaviors result from the emergence of unconscious drives into voluntary conscious behavior. The aim of psychoanalysis, the original talk therapy, is to trace symptoms to their unconscious roots and thus expose them to rational judgment.

By the 1970s, scientific studies of the brain made the whole notion of id, ego, and superego seem antiquated. Nevertheless, some resemblance between Freud’s theory and brain theory is apparent (Figure 16-1B). The limbic system and brainstem have properties akin to those of the id: they produce emotional and motivated behavior, including the will to survive and to reproduce. The posterior and the dorsolateral frontal cortices have properties akin to those of the ego: they allow us to learn and to solve everyday problems. The prefrontal neocortex has properties akin to those of the superego, enabling us to be aware of others and to learn to follow social norms. Furthermore, as abundantly displayed in earlier chapters, many processes underlying these functions are unconscious: they operate outside our awareness.

Three differences between Freud’s view and present-

564

Investigating the origins and treatment of disordered behavior is perhaps the most fascinating pursuit in studying the brain and behavior. Once, neurologists treated organic disorders of the nervous system—

With this synthesis of understanding about brain and behavior in mind, we first survey how researchers investigate the neurobiology of organic and behavioral disorders. We then examine how disorders are classified, treated, and distributed in the population and review established and emerging treatments both for neurological and for psychiatric disorders.