Chapter Introduction

171

CHAPTER 6

How Do Drugs and Hormones Influence the Brain and Behavior?

CLINICAL FOCUS 6-

6-1 PRINCIPLES OF PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY

DRUG ROUTES INTO THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

DRUG ACTION AT SYNAPSES: AGONISTS AND ANTAGONISTS

AN ACETYLCHOLINE SYNAPSE: EXAMPLES OF DRUG ACTION

TOLERANCE

EXPERIMENT 6-

SENSITIZATION

EXPERIMENT 6-

6-2 GROUPING PSYCHOACTIVE DRUGS

GROUP I: ANTIANXIETY AGENTS AND SEDATIVE-

CLINICAL FOCUS 6-

GROUP II: ANTIPSYCHOTIC AGENTS

GROUP III: ANTIDEPRESSANTS AND MOOD STABILIZERS

CLINICAL FOCUS 6-

GROUP IV: OPIOID ANALGESICS

GROUP V: PSYCHOTROPICS

6-3 FACTORS INFLUENCING INDIVIDUAL RESPONSES TO DRUGS

BEHAVIOR ON DRUGS

ADDICTION AND DEPENDENCE

SEX DIFFERENCES IN ADDICTION

6-4 EXPLAINING AND TREATING DRUG ABUSE

WANTING-

WHY DOESN’T EVERYONE ABUSE DRUGS?

TREATING DRUG ABUSE

CAN DRUGS CAUSE BRAIN DAMAGE?

CLINICAL FOCUS 6-

6-5 HORMONES

HIERARCHICAL CONTROL OF HORMONES

CLASSES AND FUNCTIONS OF HORMONES

HOMEOSTATIC HORMONES

GONADAL HORMONES

ANABOLIC–

GLUCOCORTICOIDS AND STRESS

172

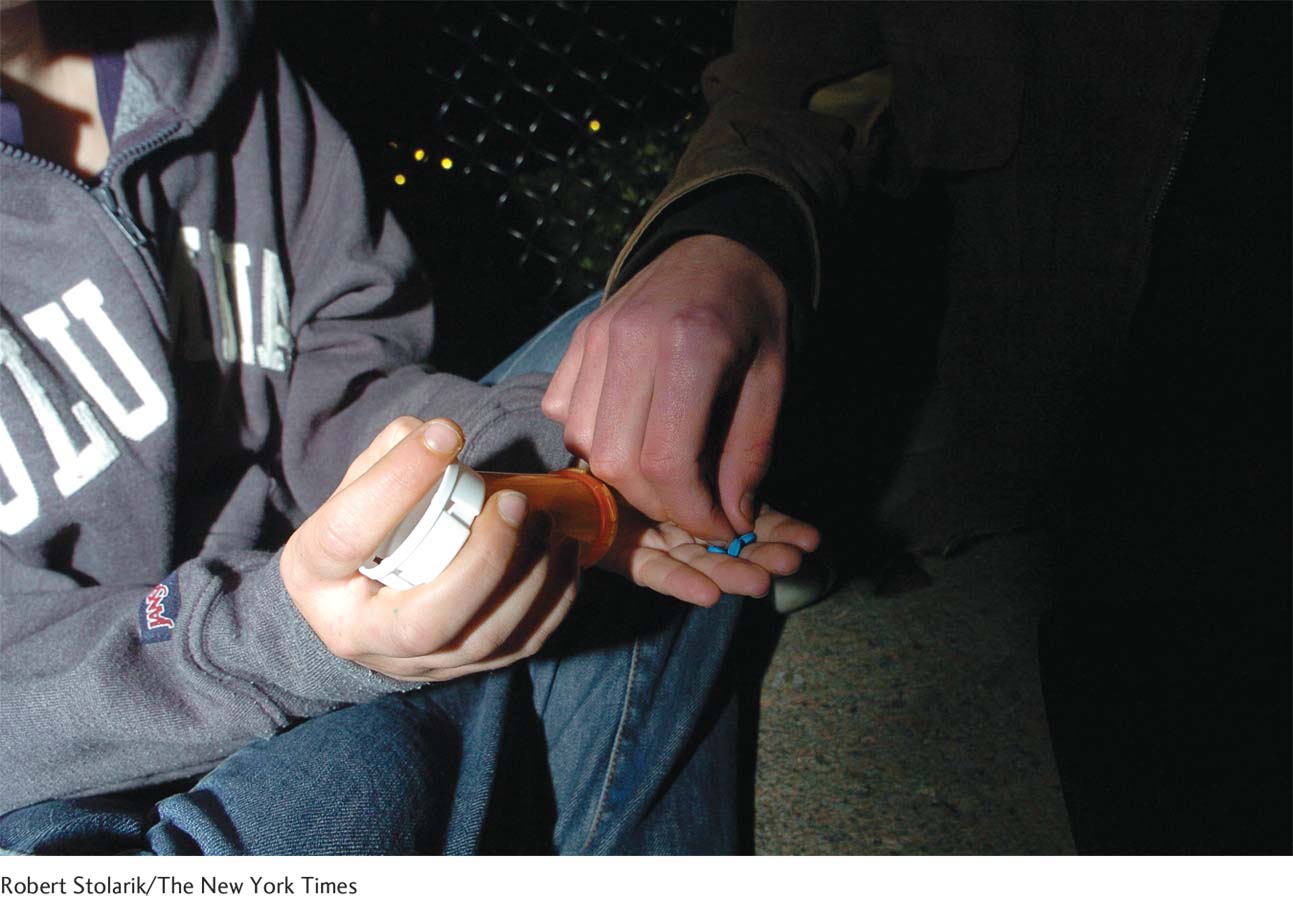

CLINICAL FOCUS 6-1

Cognitive Enhancement

A new name for an old game? An article in the preeminent science publication Nature floated the idea that certain “cognitive-

Both drugs are prescribed as a treatment for attention-

The use of cognitive enhancers is not new. In his classic paper on cocaine, Viennese psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud stated in 1884, “The main use of coca [cocaine] will undoubtedly remain that which the Indians [of Peru] have made of it for centuries . . . to increase the physical capacity of the body.” Freud later withdrew his endorsement when he realized that cocaine is addictive.

In 1937, an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association reported that a form of amphetamine, Benzedrine, improved performance on mental efficiency tests. This information was quickly disseminated among students, who began using the drug as a study aid for examinations. In the 1950s, dextroamphetamine, marketed as Dexedrine, was similarly prescribed for narcolepsy, a sleep disorder, and used illicitly by students as a study aid.

The complex neural effects of amphetamine stimulants center on learning at the synapse by means of habituation and sensitization. With repeated use for nonmedicinal purposes, the drugs can also begin to produce side effects, including sleep disruption, loss of appetite, and headaches. Some people develop cardiovascular abnormalities and/or become addicted to amphetamine.

Treating ADHD with prescription drugs is itself controversial, despite their widespread use for this purpose. According to Aagaard and Hansen (2011), assessing the adverse effects of cognitive enhancement medication is hampered because many participants drop out of studies and the duration of the studies is short.

Despite the contention that stimulant drugs can improve school and work performance by improving brain function in otherwise healthy individuals, evidence for their effectiveness, other than a transient improvement in motivation, is weak.

Psychopharmacology, the study of how drugs affect the nervous system and behavior, is the subject of this chapter. We begin by looking at the major ways drugs are administered, the routes they take to reach the central nervous system, and how they are eliminated from the body. We then group psychoactive drugs based on their major behavioral effects and on how they act on neurons. Next we consider why different people may respond differently to the same dose of a drug and why people may become addicted to drugs. Many principles related to drugs also apply to the action of hormones, the chapter’s final topic, which includes a discussion of synthetic steroids that act as hormones.

Before we examine how drugs produce their effects on the brain for good or for ill, we must raise a caution: the sheer number of neurotransmitters, receptors, and possible sites of drug action is astounding. Most drugs act at many sites in the body and brain and affect more than one neurotransmitter system, and most receptors on which drugs act display many variations. Individual differences—