Perfect Price Discrimination

Let’s return to the example of business travelers and students traveling between Bismarck and Ft. Lauderdale, illustrated in Figure 63.1, and ask what would happen if the airline could distinguish between the two groups of customers in order to charge each a different price.

Clearly, the airline would charge each group its willingness to pay—that is, the maximum that each group is willing to pay. For business travelers, the willingness to pay is $550; for students, it is $150. As we have assumed, the marginal cost is $125 and does not depend on output, making the marginal cost curve a horizontal line. And as we noted earlier, we can easily determine the airline’s profit: it is the sum of the areas of rectangle B and rectangle S.

AP® Exam Tip

A perfectly price-

Perfect price discrimination takes place when a monopolist charges each consumer his or her willingness to pay—

In this case, the consumers do not get any consumer surplus! The entire surplus is captured by the monopolist in the form of profit. When a monopolist is able to capture the entire surplus in this way, we say that the monopolist achieves perfect price discrimination.

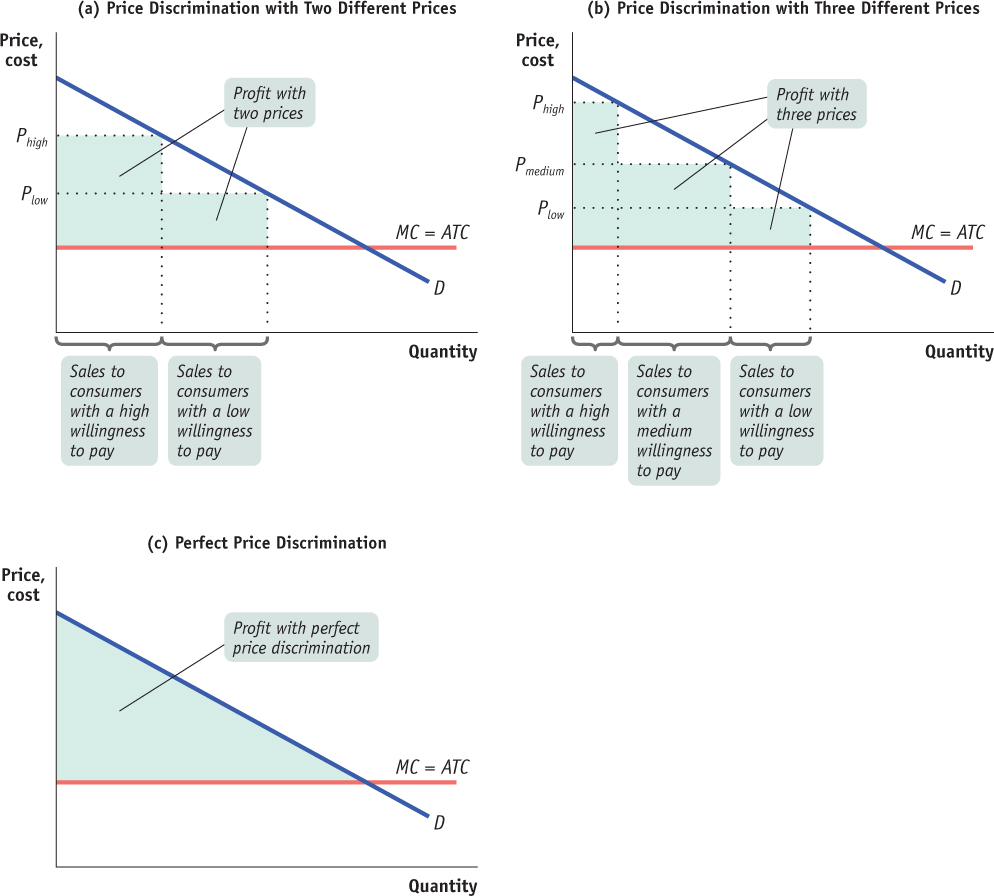

In general, the greater the number of different prices charged, the closer the monopolist is to perfect price discrimination. Figure 63.2 shows a monopolist facing a downward-

The greater the number of prices the monopolist charges, the lower the lowest price—

that is, some consumers will pay prices that approach marginal cost. The greater the number of prices the monopolist charges, the more money is extracted from consumers.

With a very large number of different prices, the picture would look like panel (c), a case of perfect price discrimination. Here, every consumer pays the most he or she is willing to pay, and the entire consumer surplus is extracted as profit.

Both our airline example and the example in Figure 63.2 can be used to make another point: a monopolist who can engage in perfect price discrimination doesn’t cause any allocative inefficiency! The reason is that the source of allocative inefficiency is eliminated: all potential consumers who are willing to purchase the good at a price equal to or above marginal cost are able to do so. The perfectly price-

Perfect price discrimination is almost never possible in practice. At a fundamental level, the inability to achieve perfect price discrimination is a problem of prices as economic signals. When prices work as economic signals, they convey the information needed to ensure that all mutually beneficial transactions will indeed occur: the market price signals the seller’s cost, and a consumer signals willingness to pay by purchasing the good whenever that willingness to pay is at least as high as the market price. The problem in reality, however, is that prices are often not perfect signals: a consumer’s true willingness to pay can be disguised, as by a business traveler who claims to be a student when buying a ticket in order to obtain a lower fare. When such disguises work, a monopolist cannot achieve perfect price discrimination. However, monopolists do try to move in the direction of perfect price discrimination through a variety of pricing strategies. Common techniques for price discrimination include the following:

Advance purchase restrictions. Prices are lower for those who purchase well in advance (or in some cases for those who purchase at the last minute). This separates those who are likely to shop for better prices from those who won’t.

Volume discounts. Often the price is lower if you buy a large quantity. For a consumer who plans to consume a lot of a good, the cost of the last unit—

the marginal cost to the consumer— is considerably less than the average price. This separates those who plan to buy a lot, and so are likely to be more sensitive to price, from those who don’t.

634

Two-

part tariffs. In a discount club like Costco or Sam’s Club (which are not monopolists but monopolistic competitors), you pay an annual fee (the first part of the tariff) in addition to the price of the item(s) you purchase (the second part of the tariff). So the full price of the first item you buy is in effect much higher than that of subsequent items, making the two- part tariff behave like a volume discount.

Our discussion also helps explain why government policies on monopoly typically focus on preventing deadweight loss, not preventing price discrimination—

635