The Economics of Pollution

Pollution is a bad thing. Yet most pollution is a side effect of activities that provide us with good things: our air is polluted by power plants generating the electricity that lights our cities, and our rivers are sullied by fertilizer runoff from farms that grow our food. Why shouldn’t we accept a certain amount of pollution as the cost of a good life?

Actually, we do. Even highly committed environmentalists don’t think that we can or should completely eliminate pollution—

To see why, we need a framework that lets us think about how much pollution a society should have. We’ll then be able to see why a market economy, left to itself, will produce more pollution than it should. We’ll start by adopting a framework to study the problem under the simplifying assumption that the amount of pollution emitted by a polluter is directly observable and controllable.

Costs and Benefits of Pollution

How much pollution should society allow? We learned previously that “how much” decisions always involve comparing the marginal benefit from an additional unit of something with the marginal cost of that additional unit. The same is true of pollution.

734

The marginal social cost of pollution is the additional cost imposed on society as a whole by an additional unit of pollution.

The marginal social cost of pollution is the additional cost imposed on society as a whole by an additional unit of pollution. For example, acid rain harms fisheries, crops, and forests; and each additional ton of sulfur dioxide released into the atmosphere increases the harm.

The marginal social benefit of pollution is the additional gain to society as a whole from an additional unit of pollution.

The marginal social benefit of pollution is the additional benefit to society from an additional unit of pollution. This concept may seem counterintuitive—

The socially optimal quantity of pollution is the quantity of pollution that society would choose if all the costs and benefits of pollution were fully accounted for.

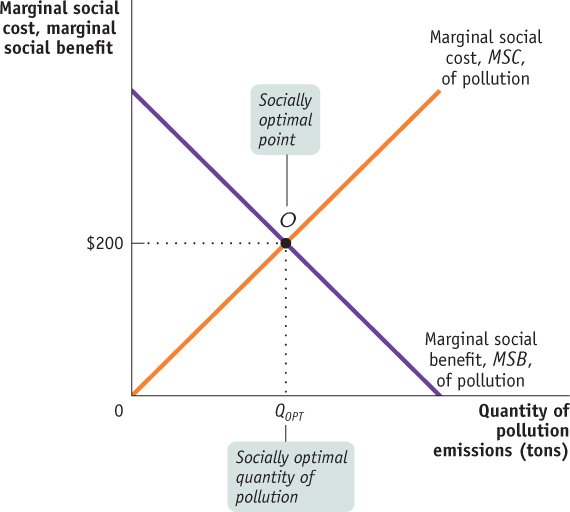

Using hypothetical numbers, Figure 74.1 shows how we can determine the socially optimal quantity of pollution—the quantity of pollution that makes society as well off as possible, taking all costs and benefits into account. The upward-

AP® Exam Tip

Treat an externalities graph like a supply and demand graph with different labels. The equilibrium point indicates the socially optimal level of the externality.

The socially optimal quantity of pollution in this example isn’t zero. It’s QOPT, the quantity corresponding to point O, where the marginal social benefit curve crosses the marginal social cost curve. At QOPT, the marginal social benefit from an additional ton of emissions and its marginal social cost are equalized at $200.

But will a market economy, left to itself, arrive at the socially optimal quantity of pollution? No, it won’t.

735

Pollution: An External Cost

Pollution yields both benefits and costs to society. But in a market economy without government intervention, those who benefit from pollution—

To see why, remember the nature of the benefits and costs from pollution. For polluters, the benefits take the form of monetary savings: by emitting an extra ton of sulfur dioxide, any given polluter saves the cost of buying expensive, low-

The costs of pollution, however, fall on people who have no say in the decision about how much pollution takes place: for example, people who fish in northeastern lakes do not control the decisions of power plants.

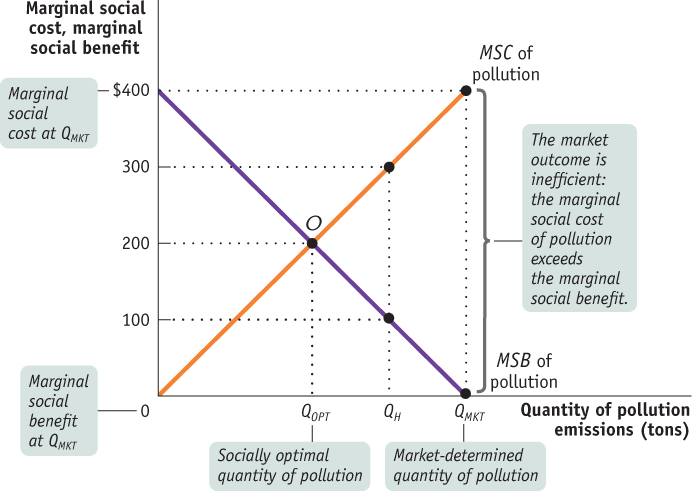

Figure 74.2 shows the result of this asymmetry between who reaps the benefits and who pays the costs. In a market economy without government intervention to protect the environment, only the benefits of pollution are taken into account in choosing the quantity of pollution. So the quantity of emissions won’t be the socially optimal quantity QOPT; it will be QMKT, the quantity at which the marginal social benefit of an additional ton of pollution is zero, but the marginal social cost of that additional ton is much larger—

The reason is that, in the absence of government intervention, those who derive the benefit from pollution—

An external cost is an uncompensated cost that an individual or a firm imposes on others.

An external benefit is a benefit that an individual or a firm confers on others without receiving compensation.

External costs and benefits are known as externalities.

External costs are negative externalities, and external benefits are positive externalities.

The environmental cost of pollution is perhaps the best-

736

We’ll see in the next module that there are also important examples of external benefits, benefits that individuals or firms confer on others without receiving compensation. External costs and external benefits are jointly known as externalities. External costs are called negative externalities and external benefits are called positive externalities.

As we’ve already suggested, externalities can lead to individual decisions that are not optimal for society as a whole. Let’s take a closer look at why, focusing on the case of pollution.

The Inefficiency of Excess Pollution

We have just shown that in the absence of government action, the quantity of pollution will be inefficient: polluters will pollute up to the point at which the marginal social benefit of pollution is zero, as shown by quantity QMKT in Figure 74.2. Recall that an outcome is inefficient if some people could be made better off without making others worse off. We have already seen why the equilibrium quantity in a perfectly competitive market with no externalities is the efficient quantity of the good, the quantity that maximizes total surplus. Here, we can use a variation of that analysis to show how the presence of a negative externality upsets that result.

Because the marginal social benefit of pollution is zero at QMKT, reducing the quantity of pollution by one ton would subtract very little from the total social benefit from pollution. In other words, the benefit to polluters from that last unit of pollution is very low—

If the quantity of pollution is reduced further, there will be more gains in total surplus, though they will be smaller. For example, if the quantity of pollution is QH in Figure 74.2, the marginal social benefit of a ton of pollution is $100, but the marginal social cost is still much higher at $300. This means that reducing the quantity of pollution by one ton leads to a net gain in total surplus of approximately $300 - $100 = $200. Thus QH is still an inefficiently high quantity of pollution. Only if the quantity of pollution is reduced to QOPT, where the marginal social cost and the marginal social benefit of an additional ton of pollution are both $200, is the outcome efficient.

Talking and Driving

Why is that woman in the car in front of us driving so erratically? Is she drunk? No, she’s talking on her cell phone.

Traffic safety experts take the risks posed by driving while talking very seriously. Using hands-

The National Safety Council urges people not to use phones while driving. But a growing number of people say that voluntary standards aren’t enough; they want the use of hand-

Why not leave the decision up to the driver? Because the risk posed by driving while talking isn’t just a risk to the driver; it’s also a safety risk to others—

Private Solutions to Externalities

737

AP® Exam Tip

For the AP® exam, be prepared to identify and explain the reasons the Coase theorem won’t always work.

Can the private sector solve the problem of externalities without government intervention? Bear in mind that when an outcome is inefficient, there is potentially a deal that makes people better off. Why don’t individuals find a way to make that deal?

According to the Coase theorem, even in the presence of externalities, an economy can always reach an efficient solution as long as transaction costs—the costs to individuals of making a deal—

In an influential 1960 article, economist and Nobel laureate Ronald Coase pointed out that in an ideal world the private sector could indeed deal with all externalities. According to the Coase theorem, even in the presence of externalities, an economy can reach an efficient solution, provided that the legal rights of the parties are clearly defined and the costs of making a deal are sufficiently low. In some cases it takes a lot of time, or even money, to bring the relevant parties together, negotiate a deal, and carry out the terms of the deal. The costs of making a deal are known as transaction costs.

To get a sense of Coase’s argument, imagine two neighbors, Mick and Christina, who both like to barbecue in their backyards on summer afternoons. Mick likes to play golden oldies on his boombox while barbecuing, but this annoys Christina, who can’t stand that kind of music.

Who prevails? You might think it depends on the legal rights involved in the case: if the law says that Mick has the right to play whatever music he wants, Christina just has to suffer; if the law says that Mick needs Christina’s consent to play music in his backyard, Mick has to live without his favorite music while barbecuing.

But as Coase pointed out, the outcome need not be determined by legal rights, because Christina and Mick can make a private deal as long as the legal rights are clearly defined. Even if Mick has the right to play his music, Christina could pay him not to. Even if Mick can’t play the music without an OK from Christina, he can offer to pay her to give that OK. These payments allow them to reach an efficient solution, regardless of who has the legal upper hand. If the benefit of the music to Mick exceeds its cost to Christina, the music will go on; if the benefit to Mick is less than the cost to Christina, there will be silence.

The implication of Coase’s analysis is that externalities need not lead to inefficiency because individuals have an incentive to make mutually beneficial deals—

Why can’t individuals always internalize externalities? Our barbecue example implicitly assumes the transaction costs are low enough for Mick and Christina to be able to make a deal. In many situations involving externalities, however, transaction costs prevent individuals from making efficient deals. Examples of transaction costs include the following:

The costs of communication among the interested parties. Such costs may be very high if many people are involved.

The costs of making legally binding agreements. Such costs may be high if expensive legal services are required.

Costly delays involved in bargaining. Even if there is a potentially beneficial deal, both sides may hold out in an effort to extract more favorable terms, leading to increased effort and forgone utility.

738

Thank You for Not Smoking

New Yorkers call them the “shiver-

Second-

According to this paper, conclusions regarding the health costs of cigarettes depend on whether the costs imposed on members of smokers’ families, including unborn children, are counted along with the costs borne by smokers. If not, the external costs of second-

In some cases, transaction costs are low enough to allow individuals to resolve externality problems. For example, while filming A League of Their Own on location in a neighborhood ballpark, director Penny Marshall paid a man $100 to stop using his noisy chainsaw nearby. But in many other cases, transaction costs are too high to make it possible to deal with externalities through private action. For example, tens of millions of people are adversely affected by acid rain. It would be prohibitively expensive to try to make a deal among all those people and all those power companies.

When transaction costs prevent the private sector from dealing with externalities, it is time to look for government solutions—