Financial Crises: Consequences and Prevention

Some economists believe that to have a developed financial system is to face the risk of financial crises. Understanding the causes and consequences of financial crises is a key to understanding how they can be prevented.

What Is a Financial Crisis?

A financial crisis is a sudden and widespread disruption of financial markets.

A financial crisis is a sudden and widespread disruption of financial markets. Such a crisis can occur when people suddenly lose faith in the ability of financial institutions to provide liquidity by bringing together those with cash to offer and those who need it. Since the banking system provides liquidity for buyers and sellers of everything from homes and cars to stocks and bonds, banking crises can easily turn into more widespread financial crises, as happened in 2008. In addition, an increase in the number and size of shadow banks in the economy can increase the scope and severity of financial crises, because shadow banks are not subject to the same regulations as depository institutions.

The Consequences of Financial Crises

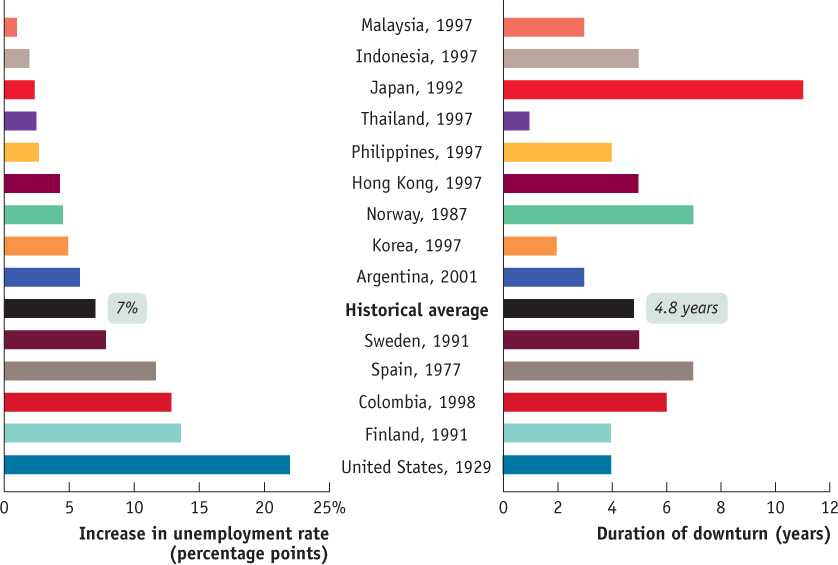

Financial crises have a significant negative effect on the economy and are closely associated with recessions. Historically, the origins of the worst economic downturns, such as the Great Depression, were tied to severe financial crises that led to decreased output and high unemployment (especially long-

A credit crunch occurs when potential borrowers can’t get credit or must pay very high interest rates.

When the financial system fails, there can be an economy-

Finally, financial crises can also lead to a decrease in the effectiveness of expansionary monetary policy intended to combat a recession. Typically, the Fed decreases the target interest rate to provide an incentive to increase spending during a recession. However, with a financial crisis, depositors, depository institutions, and borrowers all lose confidence in the system. As a result, even very low interest rates may not stimulate lending or borrowing in the economy.

Government Regulation of Financial Markets

EM-

Before the Great Depression, the government pursued a laissez-

When governments act as a lender of last resort (usually through a central bank, such as the Federal Reserve), they provide funds to banks that are unable to borrow through private credit markets. Access to credit can help solvent banks—

The 2008 Financial Crisis

In 2008, the combination of a burst housing market bubble, a loss of faith in the liquidity of financial institutions, and an unregulated shadow banking system led to a widespread disruption of financial markets.

Causes of the 2008 Financial Crisis

EM-

The collapse of Lehman Brothers—

Macroeconomic conditions

A housing bubble

Financial system linkages

Failure of government regulation

Securitization involves assembling a pool of loans and selling shares of that pool to investors.

Subprime lending involves lending to home-

A collateralized debt obligation is an asset-

A derivative is a financial contract that has value based on the performance of another asset, index, or interest rate.

The economy experienced a long period of low inflation, stable growth, and low global interest rates prior to the 2008 financial crisis. These macroeconomic conditions encouraged risk taking by shadow banks because they made it easy and cheap to borrow money. The banks searched for new ways to invest the funds they borrowed from short-

In 2008, when rumors of Lehman’s exposure in the housing market spread, the shadow bank was no longer able to borrow in short-

A credit default swap is an agreement that the seller will compensate the buyer in the event of a loan default.

Chains of debt linked Lehman to other financial institutions. Credit default swaps had been created to spread the risk of default on loans, but in fact they concentrated that risk. AIG was a large insurance company that provided those swaps. When the housing bubble burst, the large number of defaults caused AIG to collapse soon after Lehman Brothers.

The 2008 crisis was like a traditional bank run—

Moral hazard involves a distortion of incentives when someone else bears the costs of lack of care or effort.

Finally, relaxed regulation of investment banks in the shadow banking sector failed to prevent the start and spread of the financial crisis. Prior to 2008, risk taking by shadow banks increased for several reasons. To begin with, given the vital importance of the financial system to the economy as a whole, many people thought the government would step in to prevent severe problems. That is, large financial institutions were considered “too big to fail.” This led to the problem of moral hazard, which exists when a party takes excessive risks because it believes it will not bear all of the costs that could result. At the same time, the large profits earned by shadow banks further encouraged increased risk taking. Initially, the high-

Consequences of the 2008 Financial Crisis

EM-

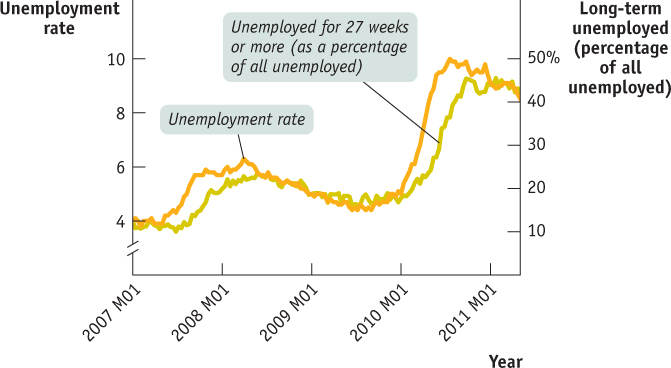

The 2008 financial crisis caused significant, prolonged damage to economies across the globe, with consequences that continued years later. For example, by the end of 2009, the United States’ economy had lost over 7 million jobs, causing the unemployment rate to increase dramatically and remain high for years after, as shown in Figure A.3. In particular, the crisis led to an increase in long-

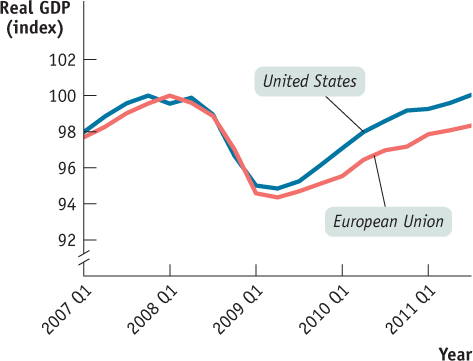

The recession in the U.S. economy sent ripples throughout the world, and the years since the recession have seen only a weak recovery. For example, Figure A.4 shows that it took more than five years for the United States to get back to the precrisis level of real GDP. In addition, in 2011–

Government Response to the 2008 Financial Crisis

EM-

The intervention of the U.S. government and the Federal Reserve at the start of the financial crisis helped to calm financial markets. The federal government bailed out some failing financial institutions and instituted the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), which involved the purchase of assets and equity from financial institutions to help strengthen the markets.

The Federal Reserve pursued an expansionary monetary policy, decreasing the federal funds rate to zero. The Fed also implemented programs to foster improved conditions in financial markets, significantly changing its own balance sheet. For example, the Fed acted as a lender of last resort by providing liquidity to financial institutions, it provided credit to borrowers and investors in key credit markets, and it put downward pressure on long-