4.3 Price Floors

The minimum wage is a legal floor on the wage rate, which is the market price of labour.

Sometimes governments intervene to push market prices up instead of down. Price floors have been widely legislated for agricultural products, such as wheat and milk, as a way to support the incomes of farmers. (In 2012, the federal government ended the monopoly position of the Canadian Wheat Board (CWB), which used government subsidies to guarantee farmers a minimum price for wheat and barley.2) Historically, there were also price floors on such services as trucking and air travel, although these were phased out by the government of Canada in the 1970s and 1980s. If you have ever worked in a fast-

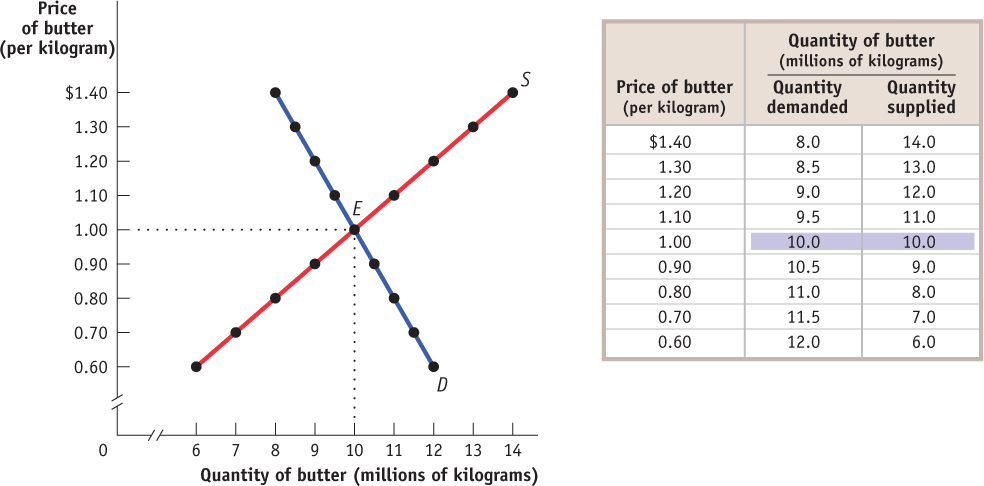

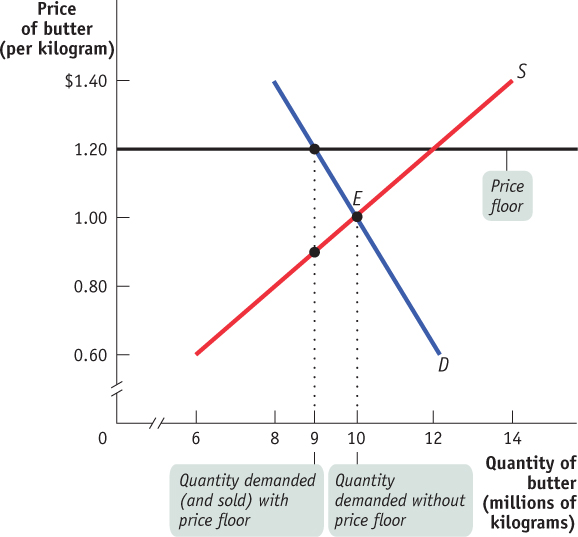

Just like price ceilings, price floors are intended to help some people but generate predictable and undesirable side effects. Figure 4-4 shows hypothetical supply and demand curves for butter. Left to itself, the market would move to equilibrium at point E, with 10 million kilograms of butter bought and sold at a price of $1 per kilogram.

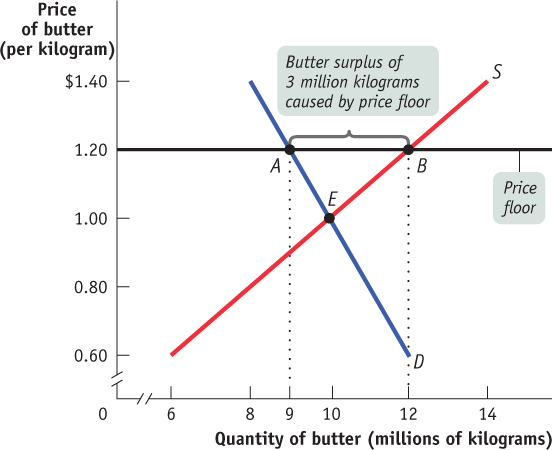

Now suppose that the government, in order to help dairy farmers, imposes a price floor on butter of $1.20 per kilogram. Its effects are shown in Figure 4-5, where the line at $1.20 represents the price floor. At a price of $1.20 per kilogram, producers would want to supply 12 million kilograms (point B on the supply curve) but consumers would want to buy only 9 million kilograms (point A on the demand curve). So the price floor leads to a persistent surplus of 3 million kilograms of butter.

Does a price floor always lead to an unwanted surplus? No. Just as in the case of a price ceiling, the floor may not be binding—

But suppose that a price floor is binding and the surplus is unwanted: what happens to it? The answer depends on government policy. In the case of agricultural price floors, governments buy up unwanted surplus. (The European Commission, which administers price floors for a number of European countries, once found itself the owner of a so-

Some countries pay exporters to sell products at a loss overseas; this is standard procedure for the European Union. Sometimes Canada gives surplus food away as foreign aid to less developed countries. In some cases, governments have actually destroyed the surplus production. For example, in 1975 about 90 million surplus eggs were destroyed in Canada. To avoid the problem of dealing with the unwanted surplus, the Canadian government typically either pays farmers not to produce the products at all or limits their ability to produce more output.

When the government is not prepared to purchase the unwanted surplus, a price floor means that would-

As we said earlier, price floors don’t always create a surplus: if a price floor is set below the equilibrium price, it is non-

How a Price Floor Causes Inefficiency

The persistent surplus that results from a price floor creates missed opportunities—

CEILINGS, FLOORS, AND QUANTITIES

A price ceiling pushes the price of a good down. A price floor pushes the price of a good up. So it’s easy to assume that the effects of a price floor are the opposite of the effects of a price ceiling. In particular, if a price ceiling reduces the quantity of a good bought and sold, doesn’t a price floor increase the quantity?

No, it doesn’t. In fact, both floors and ceilings reduce the quantity bought and sold. Why? When the quantity of a good supplied isn’t equal to the quantity demanded, the actual quantity sold is determined by the “short side” of the market—

Inefficiently Low Quantity Because a price floor raises the price of a good to consumers, it reduces the quantity of that good demanded; because sellers can’t sell more units of a good than buyers are willing to buy, a price floor reduces the quantity of a good bought and sold below the market equilibrium quantity. Notice that this is the same effect as a price ceiling. You might be tempted to think that a price floor and a price ceiling have opposite effects, but both have the effect of reducing the quantity of a good bought and sold (see Pitfalls above).

As in the case of a price ceiling, the low quantity sold is an inefficiency due to missed opportunities: price floors prevent mutually beneficial transactions from occurring, transactions that would benefit both buyers and sellers. Figure 4-6 shows the inefficiently low quantity of butter sold with a price floor on the price of butter.

Inefficient Allocation of Sales Among Sellers Like a price ceiling, a price floor can lead to inefficient allocation—but in this case inefficient allocation of sales among sellers rather than inefficient allocation to consumers.

Price floors lead to inefficient allocation of sales among sellers: those who would be willing to sell the good at the lowest price are not always those who actually manage to sell it.

An episode from the Belgian movie Rosetta, a realistic fictional story, illustrates the problem of inefficient allocation of selling opportunities quite well. Like many European countries, Belgium has a high minimum wage, and jobs for young people are scarce. At one point Rosetta, a young woman who is very anxious to work, loses her job at a fast-

Wasted Resources Also like a price ceiling, a price floor generates inefficiency by wasting resources. The most graphic examples involve government purchases of the unwanted surpluses of agricultural products caused by price floors. The surplus production is sometimes destroyed, which is pure waste; in other cases the stored produce goes, as officials euphemistically put it, “out of condition” and must be thrown away.

Price floors also lead to wasted time and effort. Consider the minimum wage. Would-

Inefficiently High Quality Again like price ceilings, price floors lead to inefficiency in the quality of goods produced.

Price floors often lead to inefficiency in that goods of inefficiently high quality are offered: some sellers offer high-

We saw that when there is a price ceiling, suppliers produce products that are of inefficiently low quality: some buyers prefer higher-

How can this be? Isn’t high quality a good thing? Yes, but only if it is worth the cost. Suppose that some suppliers spend a lot to make goods of very high quality but that this quality isn’t worth much to some consumers, who would rather receive the money spent on that quality in the form of a lower price. This represents a missed opportunity: suppliers and buyers could make a mutually beneficial deal in which buyers got goods of lower quality for a much lower price.

A good example of the inefficiency of excessive quality comes from the days when transatlantic airfares were set artificially high by international treaty. Forbidden to compete for customers by offering lower ticket prices, airlines instead offered expensive services, like lavish in-

Since the deregulation of North American airlines in the 1970s and 1980s, Canadian passengers have experienced a large decrease in ticket prices accompanied by a decrease in the quality of in-

Illegal Activity Finally, like price ceilings, price floors provide incentives for illegal activity. For example, in countries where the minimum wage is far above the equilibrium wage rate, workers desperate for jobs sometimes agree to work off the books for employers who conceal their employment from the government—

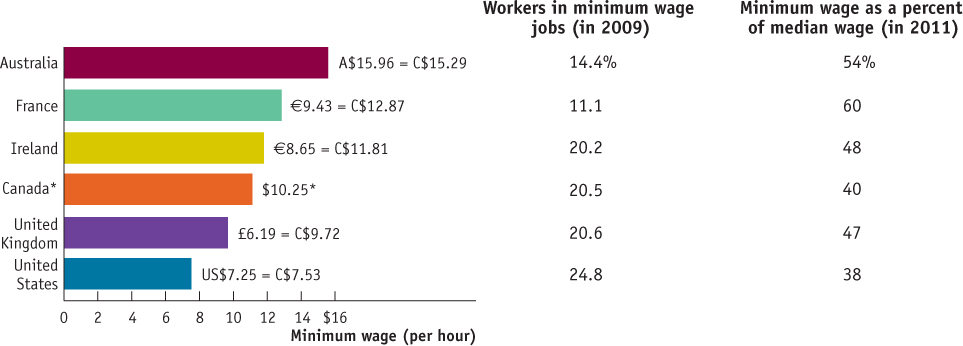

CHECK OUT THESE LOW WAGES!

As you can see in the graph below, the minimum wage rate in Canada is actually quite reasonable compared with that of other rich countries. Since minimum wages are set in national currency—

The accompanying data reveals that of these countries, the United States had the greatest percentage of workers employed in low-

Sources: OECD; Bank of Canada.

*The Canadian minimum wage varied by province and territory in 2013, ranging from $9.50 to $11.00.

So Why Are There Price Floors?

To sum up, a price floor creates various negative side effects:

A persistent surplus of the good

Inefficiency arising from the persistent surplus in the form of inefficiently low quantity transacted, inefficient allocation of sales among sellers, wasted resources, and an inefficiently high level of quality offered by some suppliers

The temptation to engage in illegal activity, particularly bribery and corruption of government officials

So why do governments impose price floors when they have so many negative side effects? The reasons are similar to those for imposing price ceilings. Government officials often disregard warnings about the consequences of price floors either because they believe that the relevant market is poorly described by the supply and demand model or, more often, because they do not understand the model. Above all, just as price ceilings are often imposed because they benefit some influential buyers of a good, price floors are often imposed because they benefit some influential sellers.

“BLACK LABOUR” IN SOUTHERN EUROPE

The best-known example of a price floor is the minimum wage. Most economists believe, however, that the minimum wage has relatively little effect on the job market if the floor is relatively low. For example, in the United States, the minimum wage was 53% of the average wage of blue-collar production workers in 1964; by 2010, despite several recent increases, it had fallen to about 44%.

The situation is different, however, in many European countries, where minimum wages have been set much higher than in Canada and the United States. This has happened despite the fact that workers in most European countries are somewhat less productive than their North American counterparts, which means that the equilibrium wage in Europe—the wage that would clear the labour market—is probably lower in Europe than in North America. Moreover, European countries often require employers to pay for health and retirement benefits, which are more extensive and so more costly than comparable American and even Canadian benefits. These mandated benefits make the actual cost of employing a European worker considerably more than the worker’s paycheque.

The result is that in Europe the price floor on labour is definitely binding: the minimum wage is well above the wage rate that would make the quantity of labour supplied by workers equal to the quantity of labour demanded by employers.

The persistent surplus that results from this price floor appears in the form of high unemployment—millions of workers, especially young workers, seek jobs but cannot find them.

In countries where the enforcement of labour laws is lax, however, there is a second, entirely predictable result: widespread evasion of the law. In both Italy and Spain, officials believe there are hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of workers who are employed by companies that pay them less than the legal minimum, fail to provide the required health and retirement benefits, or both. In many cases the jobs are simply unreported: Spanish economists estimate that about a third of the country’s reported unemployed are in the black labour market—working at unreported jobs. In fact, Spaniards waiting to collect cheques from the unemployment office have been known to complain about the long lines that keep them from getting back to work!

Employers in these countries have also found legal ways to evade the wage floor. For example, Italy’s labour regulations apply only to companies with 15 or more workers. This gives a big cost advantage to small Italian firms, many of which remain small in order to avoid paying higher wages and benefits. And sure enough, in some Italian industries there is an astonishing proliferation of tiny companies. For example, one of Italy’s most successful industries is the manufacture of fine woollen cloth, centred in the Prato region. The average textile firm in that region employs only four workers!

Quick Review

The most familiar price floor is the minimum wage. Price floors are also commonly imposed on agricultural goods.

A price floor above the equilibrium price benefits successful sellers but causes predictable adverse effects such as a persistent surplus, which leads to four kinds of inefficiencies: inefficiently low quantity transacted, inefficient allocation of sales among sellers, wasted resources, and inefficiently high quality.

Price floors encourage illegal activity, such as workers who work off the books, often leading to official corruption.

Check Your Understanding 4-2

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 4-2

Question 4.3

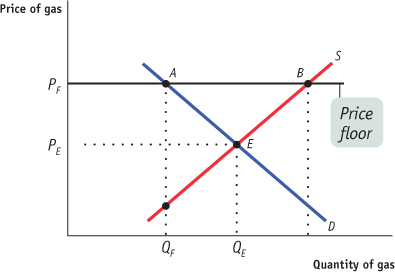

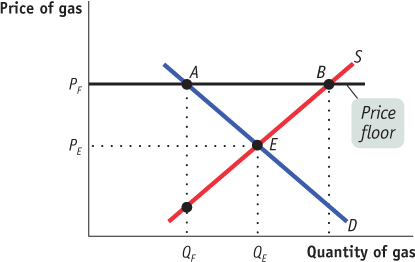

A provincial legislature mandates a price floor for gasoline of PF per litre. Assess the following statements and illustrate your answer using the figure provided.

Proponents of the law claim it will increase the income of gas station owners. Opponents claim it will hurt gas station owners because they will lose customers.

Proponents claim consumers will be better off because gas stations will provide better service. Opponents claim consumers will be generally worse off because they prefer to buy gas at cheaper prices.

Proponents claim that they are helping gas station owners without hurting anyone else. Opponents claim that consumers are hurt and will end up doing things like buying gas across the border or on the black market.

Some gas station owners will benefit from getting a higher price. QF indicates the sales made by these owners. But some will lose; there are those who make sales at the market equilibrium price of PE but do not make sales at the regulated price of PF. These missed sales are indicated on the graph by the fall in the quantity demanded along the demand curve, from point E to point A.

Those who buy gas at the higher price of PF will probably receive better service; this is an example of inefficiently high quality caused by a price floor as gas station owners compete on quality rather than price. But opponents are correct to claim that consumers are generally worse off—those who buy at PF would have been happy to buy at PE, and many who were willing to buy at a price between PE and PF are now unwilling to buy. This is indicated on the graph by the fall in the quantity demanded along the demand curve, from point E to point A.

Proponents are wrong because consumers and some gas station owners are hurt by the price floor. Every price floor creates “missed opportunities”—desirable transactions between consumers and station owners that never take place. Moreover, the inefficiency of wasted resources arises as consumers spend time and money driving to other provinces or to the United States. The price floor also tempts people to engage in black market activity. With the price floor, only QF units are sold. But at prices between PE and PF, there are drivers who cumulatively want to buy more than QF and owners who are willing to sell to them, a situation likely to lead to illegal activity.