6.4 Inflation and Deflation

In 1991, a Canadian worker who was paid by the hour earned $14.01 per hour, on average. By 2011, the average wage had risen to $21.75 per hour. Similarly, in 1991, a Canadian worker on a fixed salary earned the equivalent of $18.70 per hour, on average. By 2011, this salary had risen to $31.64 per hour, on average.

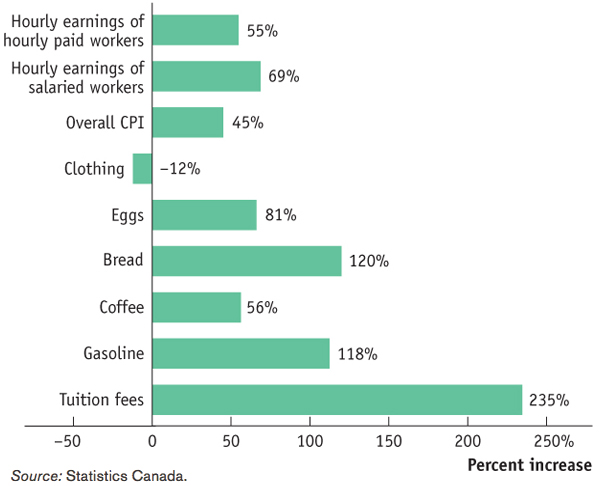

But wait. Canadian workers were paid much more in 2011, but they also faced a much higher cost of living. For example, from 1991 to 2011 the price of coffee rose by 56% and the price of gasoline rose by 118%. Figure 6-8 compares the percentage increase in hourly earnings between 1991 and 2011 with the increases in the prices of some standard items: the average worker’s paycheque went further in terms of some goods, but less far in terms of others. Although income for both types of workers increased more than the overall increase in the cost of living (45%), salaried workers fared better than hourly paid workers. Salaried workers’ hourly pay rose by 24 percentage points more than the Consumer Price Index (CPI) did over this period compared to only a 10 percentage point gain for their hourly paid counterparts over the CPI.

Source: Statistics Canada.

A rising overall level of prices is inflation.

The point is that between 1991 and 2011 the economy experienced substantial inflation: a rise in the overall level of prices. Understanding the causes of inflation and its opposite, deflation—a fall in the overall level of prices—

A falling overall level of prices is deflation.

The Causes of Inflation and Deflation

You might think that changes in the overall level of prices are just a matter of supply and demand. For example, higher gasoline prices reflect the higher price of crude oil, and higher crude oil prices reflect such factors as the exhaustion of major oil fields, growing demand from China and other emerging economies as more people grow rich enough to buy cars, and so on. Can’t we just add up what happens in each of these markets to find out what happens to the overall level of prices?

The answer is no, we can’t. Supply and demand can only explain why a particular good or service becomes more expensive relative to other goods and services. It can’t explain why, for example, the price of chicken has risen over time in spite of the facts that chicken production has become more efficient (you don’t want to know) and that chicken has become substantially cheaper compared to other goods.

What causes the overall level of prices to rise or fall? As we’ll learn in Chapter 8, in the short run, movements in inflation are closely related to the business cycle. When the economy is depressed and jobs are hard to find, inflation tends to fall; when the economy is booming, inflation tends to rise. For example, prices of most goods and services fell sharply during the terrible recession of 1929–1933.

In the long run, by contrast, the overall level of prices is mainly determined by changes in the money supply, the total quantity of assets that can be readily used to make purchases. As we’ll see in Chapter 16, hyperinflation, in which prices rise by thousands or hundreds of thousands of percent, invariably occurs when governments print money to pay a large part of their bills.

The Pain of Inflation and Deflation

Both inflation and deflation can pose problems for the economy. Here are two examples: inflation discourages people from holding on to cash, because cash loses value over time if the overall price level is rising. That is, inflation causes the amount of goods and services you can buy with a given amount of cash to fall. In extreme cases, people stop holding cash altogether and turn to barter. Deflation can cause the reverse problem. If the price level is falling, cash gains value over time as it buys more and more goods and services than previously. In other words, the amount of goods and sevices you can buy with a given amount of cash increases. So holding on to it can become more attractive than spending on some goods or investing in new factories and other productive assets. This can deepen a recession.

We’ll describe other costs of inflation and deflation in Chapters 8 and 16. For now, let’s just note that, in general, economists regard price stability—in which the overall level of prices is changing, if at all, only slowly—as a desirable goal. Price stability is a goal that seemed far out of reach for much of the post–World War II period but was achieved to most macroeconomists’ satisfaction in the 1990s.

The economy has price stability when the overall level of prices changes slowly or not at all.

A FAST (FOOD) MEASURE OF INFLATION

The first McDonald’s in Canada opened in Richmond, British Columbia, in 1967. It offered fast service—it was, indeed, one of Canada’s original fast-food restaurants. And it was also very inexpensive: a hamburger cost about $0.39. By 2012, a hamburger at a typical Canadian McDonald’s cost almost four times as much, about $1.39. Has McDonald’s lost touch with its fast-food roots? Have burgers become luxury cuisine?

No. In fact compared with other consumer goods, a burger is a better bargain today than it was in 1967. Burger prices were almost four times as high in 2012 as they were in 1967. But according to the Bank of Canada inflation calculator, most goods costing $0.39 in 1967 cost $2.65 in 2012, which is almost seven times as much as in 1967.

Quick Review

A dollar today doesn’t buy what it did in 1991, because the prices of most goods have risen. This rise in the overall price level has wiped out most, if not all, of the wage increases received by the typical Canadian worker over the past 20 years.

One area of macroeconomic study is in the overall level of prices. Because either inflation or deflation can cause problems for the economy, economists typically advocate maintaining price stability.

Check Your Understanding 6-4

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 6-4

Question 6.7

Which of these sound like inflation, which sound like deflation, and which are ambiguous?

Gasoline prices are up 10%, food prices are down 20%, and the prices of most services are up 1–2%.

Gas prices have doubled, food prices are up 50%, and most services seem to be up 5% or 10%.

Gas prices haven’t changed, food prices are way down, and services have gotten cheaper, too.

As some prices have risen but other prices have fallen, there may be overall inflation or deflation. The answer is ambiguous.

As all prices have risen significantly, this sounds like inflation.

As most prices have fallen and others have not changed, this sounds like deflation.