9.3 Why Growth Rates Differ

In 1820, according to estimates by the economic historian Angus Maddison, Mexico had somewhat higher real GDP per capita than Japan. Today, Japan has higher real GDP per capita than most European nations and Mexico is a poor country, though by no means among the poorest. The difference? Over the long run—

As this example illustrates, even small differences in growth rates have large consequences over the long run. So why do growth rates differ across countries and across periods of time?

Explaining Differences in Growth Rates

As one might expect, economies with rapid growth tend to be economies that add physical capital, increase their human capital, or experience rapid technological progress. Striking economic success stories, like Japan in the 1950s and 1960s or China today, tend to be countries that do all three: rapidly add to their physical capital through high savings and investment spending, upgrade their educational level, and make fast technological progress. Evidence also points to the importance of government policies, property rights, political stability, and good governance in fostering the sources of growth.

Savings and Investment Spending One reason for differences in growth rates between countries is that some countries are increasing their stock of physical capital much more rapidly than others, through high rates of investment spending. In the 1960s, Japan was the fastest-

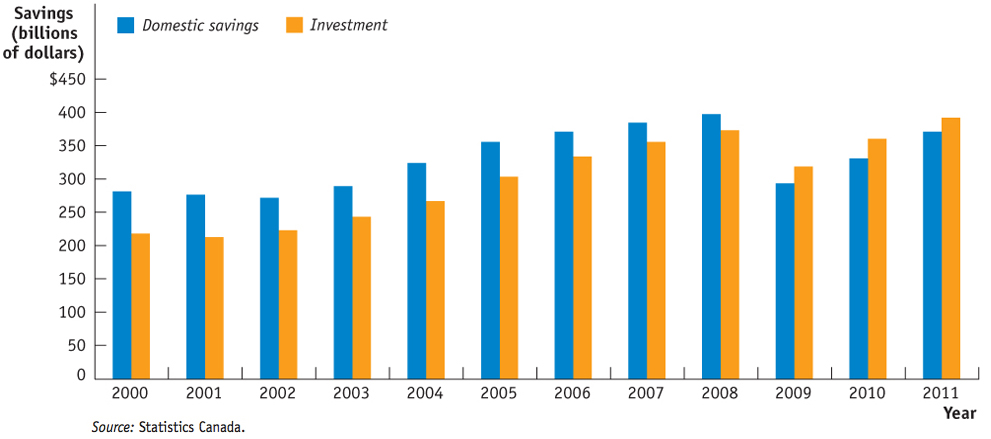

Where does the money for high investment spending come from? From savings. In the next chapter, we’ll analyze how financial markets channel savings into investment spending. For now, however, the key point is that investment spending must be paid for either out of domestic (national) savings or out of foreign savings. Domestic savings refer to the savings within the country, which can come from households and/or the government. Foreign savings, as you might expect, are savings that come from foreign countries. If a country finances its investment with foreign savings, it is borrowing from abroad.

Foreign capital has played an important role in the long-

Source: Statistics Canada.

One reason for differences in growth rates, then, is that countries add different amounts to their stocks of physical capital because they have different rates of savings and investment spending.

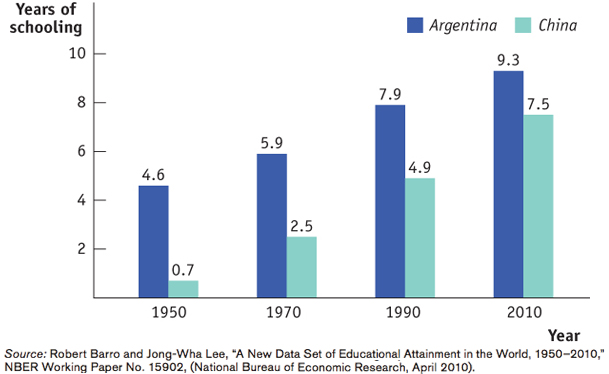

Education Just as countries differ substantially in the rate at which they add to their physical capital, there have been large differences in the rate at which countries add to their human capital through education.

A case in point is the comparison between Argentina and China. In both countries the average educational level has risen steadily over time, but it has risen much faster in China. Figure 9-9 shows the average years of education of adults in China, which we have highlighted as a spectacular example of long-

Source: Robert Barro and Jong-

Research and Development The advance of technology is a key force behind economic growth. What drives technological progress?

Scientific advances make new technologies possible. To take the most spectacular example in today’s world, the semiconductor chip—

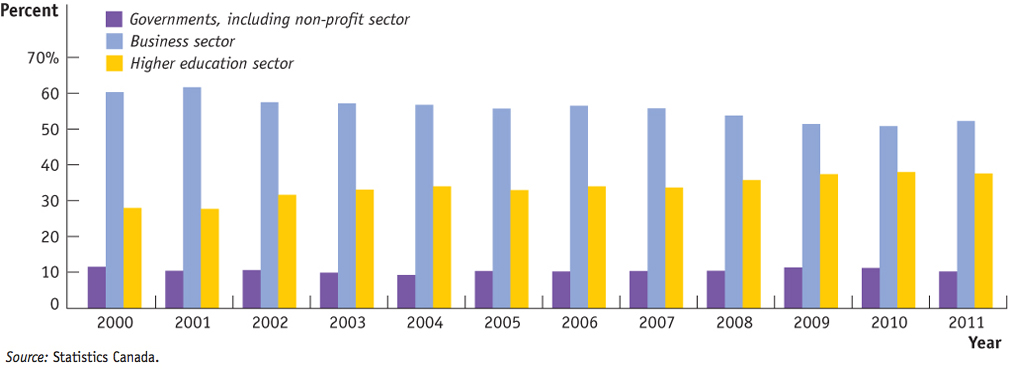

Research and development, or R&D, is spending to create and implement new technologies.

But science alone is not enough: scientific knowledge must be translated into useful products and processes. And that often requires devoting a lot of resources to research and development, or R&D, spending to create new technologies and apply them to practical use.

Figure 9-10 breaks down the shares of R&D performed by different sectors in Canada between 2000 and 2011. Although some research and development is conducted by the government and higher education sectors, the largest share of R&D is performed by the business sector. The figure shows that the business sector conducts more than half of the country’s R&D, while governments are only responsible for about 10% of the country’s R&D. The role of the higher education sector in R&D performance has become more important over time—

Source: Statistics Canada.

The Role of Government in Promoting Economic Growth

Governments can play an important role in promoting—

PRIVATE SECTOR AND R&D

Alexander Graham Bell, one of Canada’s most famous scientific innovators, is best known as the inventor of the first telephone, a major milestone in telecommunications technology. His invention stimulated the development of other communication devices, and to some extent, today’s smartphones are an extension of his invention.

Bell was also an important early pioneer of research and development. He received his telephone patent from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office on March 7, 1876. The patent gave him huge financial rewards: it was the most valuable asset of the Bell Telephone Company, the predecessor of American Telephone & Telegraph (AT&T). Bell continued to conduct scientific research throughout the rest of his life. He was particularly interested in technologies to assist deaf and hearing impaired people, like his wife. He also financed other people’s research; for instance, he funded the early atomic experiments of American physicist A.A. Michelson. Bell set a good example of how individuals and the private sector can contribute to research and development. Nowadays, the private and business sectors play the predominant role in an economy’s R&D.

Government Policies Government policies can increase the economy’s growth rate through four main channels.

Roads, power lines, ports, information networks, and other underpinnings for economic activity are known as infrastructure.

1. GOVERNMENT SUBSIDIES TO INFRASTRUCTURE Governments play an important direct role in building infrastructure: roads, power lines, ports, information networks, and other large-

Poor infrastructure, such as a power grid that frequently fails and cuts off electricity, is a major obstacle to economic growth in many countries. To provide good infrastructure, an economy must not only be able to afford it, but it must also have the political discipline to maintain it.

Perhaps the most crucial infrastructure is something we, in Canada rarely think about: basic public health measures in the form of a clean water supply and disease control. As we’ll see in the next section, poor health infrastructure is a major obstacle to economic growth in poor countries, especially those in Africa.

OLD EUROPE AND NEW TECHNOLOGY

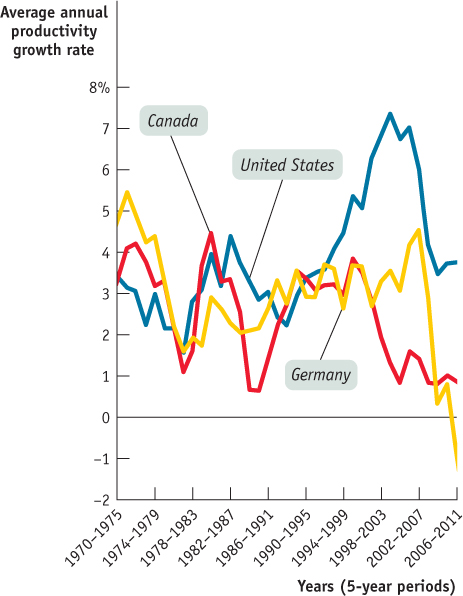

The accompanying figure shows the five-

Throughout much of the mid-

Source: The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

2. GOVERNMENT SUBSIDIES TO EDUCATION In contrast to physical capital, which is mainly created by private investment spending, much of an economy’s human capital is the result of government spending on education. In Canada, all levels of government—

3. GOVERNMENT SUBSIDIES TO R&D Technological progress is largely the result of private initiative. Governments help promote R&D in the business sector through different programs and initiatives. For example, the federal government funds the Scientific Research and Experimental Development (SR&ED) tax incentive program, which allows businesses to receive cash refunds and/or tax credits and deductions for their spending on R&D in Canada. Governments also directly perform R&D; indeed, some important R&D projects, such as those on water/food safety, health, and environmental stress, are conducted by Canadian government agencies. In the upcoming Economics in Action, we describe Brazil’s agricultural boom, which was made possible by government researchers who made discoveries that expanded the amount of arable land in Brazil, as well as developing new varieties of crops that flourish in Brazil’s climate.

4. MAINTAINING A WELL-

If a country’s citizens trust their banks, they will place their savings in bank deposits, which the banks will then lend to their business customers. But if people don’t trust their banks, they will hoard gold or foreign currency, keeping their savings in safe deposit boxes or under the mattress, where it cannot be turned into productive investment spending. As we’ll discuss later, a well-

Protection of Property Rights Property rights are the rights of owners of valuable items to dispose of those items as they choose. A subset, intellectual property rights, are the rights of an innovator to accrue the rewards of her innovation. The state of property rights generally, and intellectual property rights in particular, are important factors in explaining differences in growth rates across economies. Why? Because no one would bother to spend the effort and resources required to innovate if someone else could appropriate that innovation and capture the rewards. So, for innovation to flourish, intellectual property rights must receive protection.

Sometimes this is accomplished by the nature of the innovation: it may be too difficult or expensive to copy. But, generally, the government has to protect intellectual property rights. A patent is a government-

THE NEW GROWTH THEORY

Until the 1990s, economic models of technological progress assumed that what drove innovation was a mystery—

At any point in time, an economy has a stock of knowledge capital—

Yet, as Romer pointed out, there is a severe wrinkle in this story: because knowledge is shared throughout the economy, it may be very difficult for an innovator to capture the rewards of his or her innovation as others exploit the innovation for their own interests. So in the New Growth Theory, government protection of intellectual property rights is critical to furthering technological progress. In addition, governments, institutions, and firms can enhance technological progress by subsidizing investments in education and research and development, which, in turn, can increase the stock of knowledge capital.

By giving us a better model of where technological progress comes from, the New Growth Theory makes clear how important the policies of government, institutions, and firms are in fostering it.

Political Stability and Good Governance There’s not much point in investing in a business if rioting mobs are likely to destroy it, or saving your money if someone with political connections can steal it. Political stability and good governance (including the protection of property rights) are essential ingredients in fostering economic growth in the long run.

Long-

Canadians take these preconditions for granted, but they are by no means guaranteed. Aside from the disruption caused by war or revolution, many countries find that their economic growth suffers due to corruption among the government officials who should be enforcing the law. For example, until 1991 the Indian government imposed many bureaucratic restrictions on businesses, which often had to bribe government officials to get approval for even routine activities—

Even when the government isn’t corrupt, excessive government intervention can be a brake on economic growth. If large parts of the economy are supported by government subsidies, protected from imports, subject to unnecessary monopolization, or otherwise insulated from competition, productivity tends to suffer because of a lack of incentives. As we’ll see in the next section, excessive government intervention is one often-

THE BRAZILIAN BREADBASKET

Awry Brazilian joke says that “Brazil is the country of the future—

In recent years, however, Brazil’s economy has made a better showing, especially in agriculture. This success depends on exploiting a natural resource, the tropical savannah land known as the cerrado. Until a quarter-

The Brazilian Enterprise for Agricultural and Livestock Research, a government-

What still limits Brazil’s growth? Infrastructure. According to a report in the New York Times, Brazilian farmers are “concerned about the lack of reliable highways, railways and barge routes, which adds to the cost of doing business.” Recognizing this, the Brazilian government is investing in infrastructure, and Brazilian agriculture is continuing to expand. The country has already overtaken the United States as the world’s largest beef exporter and may not be far behind in soybeans.

Quick Review

Countries differ greatly in their growth rates of real GDP per capita due to differences in the rates at which they accumulate physical capital and human capital as well as differences in technological progress. A prime cause of differences in growth rates is differences in rates of domestic savings and investment spending as well as differences in education levels, and research and development, or R&D, levels. R&D largely drives technological progress.

Government actions can promote or hinder the sources of long-

term growth. Government policies that directly promote growth are subsidies to infrastructure, particularly public health infrastructure, subsidies to education, subsidies to R&D, and the maintenance of a well-

functioning financial system. Governments improve the environment for growth by protecting property rights (particularly intellectual property rights through patents), by providing political stability, and through good governance. Poor governance includes corruption and excessive government intervention.

Check Your Understanding 9-3

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 9-3

Question 9.7

Explain the link between a country’s growth rate, its investment spending as a percent of GDP, and its domestic savings.

A country that has high domestic savings is able to achieve a high rate of investment spending as a percent of GDP. This, in turn, allows the country to achieve a high growth rate.

Question 9.8

Explain how the accumulation of human capital helps promote long-

By accumulating more human capital, the economy would have more productive resources and grow faster. The government can speed up the accumulation of human capital by subsidizing education and R&D, and protecting property rights.

Question 9.9

During the 1990s in the former U.S.S.R., a lot of property was seized and controlled by those in power. How might this have affected the country’s growth rate at that time? Explain.

It is likely that these events resulted in a fall in the country’s growth rate because the lack of property rights would have dissuaded people from making investments in productive capacity.