9.5 Is World Growth Sustainable?

Earlier in this chapter we described the views of Thomas Malthus, the early-

Sustainable long-run economic growth is long-

But will this always be the case? Some skeptics have expressed doubt about whether sustainable long-run economic growth is possible—

Natural Resources and Growth, Revisited

In 1972, a group of scientists called The Club of Rome made a big splash with a book titled The Limits to Growth, which argued that long-

Source: The U.S. Energy Information Administration.

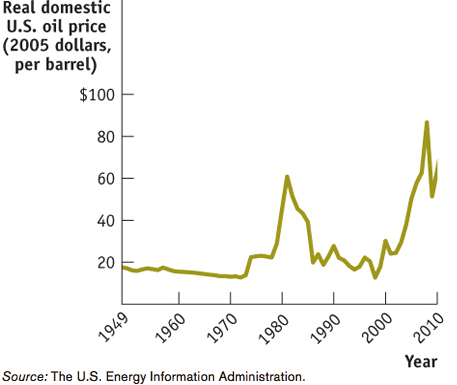

Differing views about the impact of limited natural resources on long-

How large are the supplies of key natural resources?

How effective will technology be at finding alternatives to natural resources?

Can long-

run economic growth continue in the face of resource scarcity?

It’s mainly up to geologists to answer the first question. Unfortunately, there’s wide disagreement among the experts, especially about the prospects for future oil production. Some analysts believe that there is enough untapped oil in the ground that world oil production can continue to rise for several decades. Others, including a number of oil company executives, believe that the growing difficulty of finding new oil fields will cause oil production to plateau—

The answer to the second question, whether there are alternatives to natural resources, has to come from engineers. There’s no question that there are many alternatives to the natural resources currently being depleted, some of which are already being exploited. For example, “unconventional” oil extracted from the Alberta oil sands is already making a significant contribution to world oil supplies, and electricity generated by wind turbines is rapidly becoming big business.

The third question, whether economies can continue to grow in the face of resource scarcity, is mainly a question for economists. And most, though not all, economists are optimistic: they believe that modern economies can find ways to work around limits on the supply of natural resources. One reason for this optimism is the fact that resource scarcity leads to high resource prices. These high prices in turn provide strong incentives to conserve the scarce resource and to find alternatives.

Figure 9-14 compares Canada’s real GDP per capita and oil consumption from 1980 to 2011. Over this 31-year timespan, there seems to have been a close positive relationship between oil consumption and real GDP per capita, with some noticeable exceptions. In the early 1980s and again in the mid-

Sources: Oil consumption: The U.S. Energy Information Administration; Real GDP per capita: Statistics Canada.

Given such responses to prices, economists generally tend to see resource scarcity as a problem that modern economies handle fairly well, and so not a fundamental limit to long-

Economic Growth and the Environment

Economic growth, other things equal, tends to increase the human impact on the environment. For example, China’s spectacular economic growth has also brought a spectacular increase in air pollution in that nation’s cities.

Other things, however, aren’t necessarily equal: countries can and do take action to protect their environments. In fact, air and water quality in today’s developed countries is generally much better than it was a few decades ago. London’s famous “fog”—actually a form of air pollution, which killed 4000 people during a two-week episode in 1952—is gone, thanks to regulations that virtually eliminated the use of coal heat. The equally famous smog of Los Angeles, although not extinguished, is far less severe than it was in the 1960s and early 1970s, again thanks to pollution regulations.

While we have seen and heard of local environmental success stories in the past, there is still today widespread concern about the environmental impacts of continuing economic growth. The true scale of the problem, however, has been recognized, and environmental success stories now mainly deal with economic growth and human impact on a national level. In Canada, this includes attempts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles, federal and provincial government incentives to induce Canadians to buy more fuel-efficient vehicles, and promotion of environmentally friendly transportation alternatives. Furthermore, nations are now addressing global environmental issues—the adverse impacts on the environment of the Earth as a whole by worldwide economic growth. The greatest of these issues involves the impact of fossil fuel consumption on the world’s climate.

Burning coal and oil releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. There is broad scientific consensus that rising levels of carbon dioxide and other gases are causing a greenhouse effect on the Earth, trapping more of the sun’s energy and raising the planet’s overall temperature. And rising temperatures may impose high human and economic costs: rising sea levels may flood coastal areas; changing climate may disrupt agriculture, especially in poor countries; and so on.

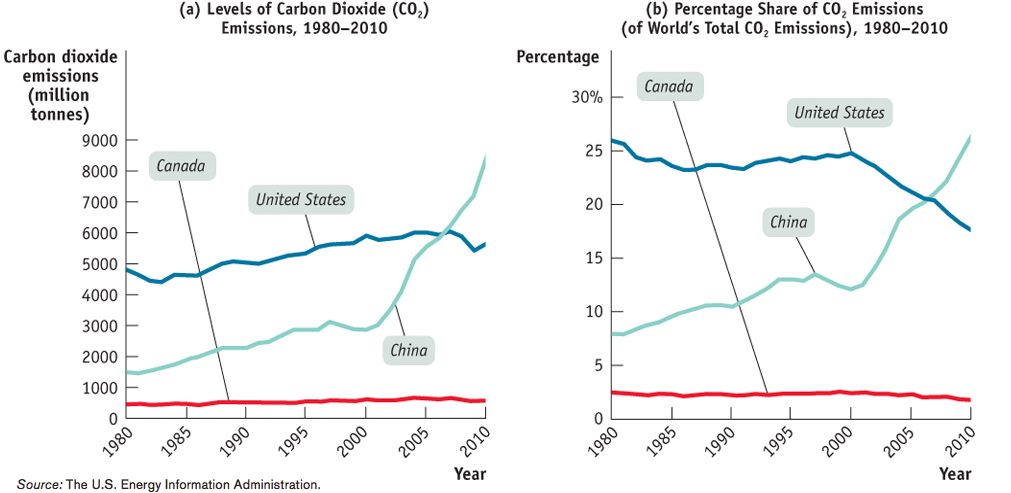

The problem of climate change is clearly linked to economic growth. Figure 9-15 shows carbon dioxide emission from Canada, the United States, and China between 1980 and 2010. Historically, the wealthy nations have been responsible for the bulk of these emissions because they have consumed far more energy per person than poorer countries. As China and other emerging economies have grown, however, they have begun to consume much more energy and emit much more carbon dioxide.

Source: The U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Is it possible to continue long-run economic growth while curbing the emissions of greenhouse gases? The answer, according to most economists who have studied the issue, is yes. It should be possible to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in a wide variety of ways, ranging from the use of non-fossil-fuel energy sources such as wind, solar, and nuclear power; to preventive measures such as carbon sequestration (capturing the carbon dioxide from power plants and storing it); to simpler things like designing buildings so that they’re easier to keep warm in winter and cool in summer. Such measures would impose costs on the economy, but the best available estimates suggest that even a large reduction in greenhouse gas emissions over the next few decades would only modestly dent the long-term rise in real GDP per capita.

The problem is how to make all of this happen. Unlike resource scarcity, environmental problems don’t automatically provide incentives for changed behaviour. Pollution is an example of a negative externality, a cost that individuals or firms impose on others without having to offer compensation. In the absence of government intervention, individuals and firms have no incentive to reduce negative externalities, which is why it took regulation to reduce air pollution in North America’s cities. And as Nicholas Stern, the author of an influential report on climate change, put it, greenhouse gas emissions are “the mother of all externalities.”

So there is a broad consensus among economists—although there are some dissenters—that government action is needed to deal with climate change. There is also broad consensus that this action should take the form of market-based incentives, either in the form of a carbon tax—a tax per unit of carbon emitted—or a cap and trade system in which the total amount of emissions is capped, and producers must buy licenses to emit greenhouse gases. There is, however, considerable dispute about how much action is appropriate, reflecting both uncertainty about the costs and benefits and scientific uncertainty about the pace and extent of climate change.

There are also several aspects of the climate change problem that make it much more difficult to deal with than, say, fog in London. One is the problem of taking the long view. The impact of greenhouse gas emissions on the climate is very gradual: carbon dioxide put into the atmosphere today won’t have its full effect on the climate for several generations. As a result, there is the political problem of persuading voters to accept pain today in return for gains that will benefit their children, grandchildren, or even great-grandchildren.

There is also a difficult problem of international burden sharing. As Figure 9-15 shows, today’s rich economies have historically been responsible for most greenhouse gas emissions, but newly emerging economies like China are responsible for most of the recent growth. Inevitably, rich countries are reluctant to pay the price of reducing emissions only to have their efforts frustrated by rapidly growing emissions from new players. On the other hand, countries like China, which are still relatively poor, consider it unfair that they should be expected to bear the burden of protecting an environment threatened by the past actions of rich nations.

The general moral of this story is that it is possible to reconcile long-run economic growth with environmental protection. The main question is one of getting political consensus around the necessary policies.

THE COST OF CLIMATE PROTECTION

According to its own brochure, the National Round Table on the Economy and the Environment (NRTEE) has “a direct mandate from Parliament to engage Canadians in the generation and promotion of sustainable development advice and solutions.” In 2012, the NRTEE delivered a report called “Reality Check: The State of Climate Progress in Canada.” The report was unequivocal: Canada will need to do much more in order to achieve its “2020 GHG (greenhouse gases) emission reductions” target of 17% below 2005 levels.

Most people acknowledge that countries need to take further action to lower harmful emissions—and they must do so now; otherwise, climate change may lead to catastrophic effects on the planet and the economy. According to the NRTEE, global warming could cost Canada about $5 billion a year by 2020 and between $21 and $43 billion a year by the 2050s.6

So why are some people or corporations reluctant to take further steps? They may feel that the cost of investing in programs and strategies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is too high, that there is little incentive to make such investments, or that investment in this area will take away from investment in other areas and thus jeopardize the nation’s economic growth. To change this attitude, governments could, for example, provide subsidies and/or tax credits to firms and households that adopt strategies to conserve the environment.

On the brighter side, Environment Canada noted that between 2009 and 2010 greenhouse gas emissions in Canada remained relatively steady, rather than increasing, and that the economy still enjoyed a growth of 3.2%. This result could support the argument that we can tackle climate change without sacrificing economic growth.

Quick Review

There’s wide disagreement about whether it is possible to have sustainable long-run economic growth. However, economists generally believe that modern economies can find ways to alleviate limits to growth from natural resource scarcity through the price response that promotes conservation and the creation of alternatives.

Overcoming the limits to growth arising from environmental degradation is more difficult because it requires effective government intervention. Limiting the emission of greenhouse gases would require only a modest reduction in the growth rate.

There is broad consensus that government action to address climate change and greenhouse gases should be in the form of market-based incentives, like a carbon tax or a cap and trade system. It will also require rich and poor countries to come to some agreement on how the cost of emissions reductions will be shared.

Check Your Understanding 9-5

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 9-5

Question 9.13

Are economists typically more concerned about the limits to growth imposed by environmental degradation or those imposed by resource scarcity? Explain, noting the role of negative externalities in your answer.

Economists are typically more concerned about environmental degradation than resource scarcity. The reason is that in modern economies the price response tends to alleviate the limits imposed by resource scarcity through conservation and the development of alternatives. However, because environmental degradation involves a negative externality—a cost imposed by individuals or firms on others without the requirement to pay compensation—effective government intervention is required to address it. As a result, economists are more concerned about the limits to growth imposed by environmental degradation because a market response would be inadequate.

Question 9.14

What is the link between greenhouse gas emissions and growth? What is the expected effect on growth from emissions reduction? Why is international burden sharing of greenhouse gas emissions reduction a contentious problem?

Growth increases a country’s greenhouse gas emissions. The current best estimates are that a large reduction in emissions will result in only a modest reduction in growth. The international burden sharing of greenhouse gas emissions reduction is contentious because rich countries are reluctant to pay the costs of reducing their emissions only to see newly emerging countries like China rapidly increase their emissions. Yet most of the current accumulation of gases is due to the past actions of rich countries. Poorer countries like China are equally reluctant to sacrifice their growth to pay for the past actions of rich countries.

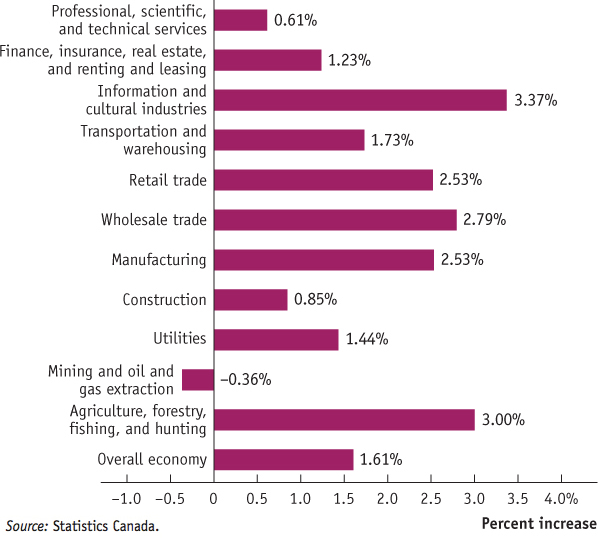

sources of Canada’s Labour Productivity Growth, 1970–2010

During the past four decades, the Canadian economy has grown. Figure 9-16 shows the average labour productivity growth between 1970 and 2010 for the whole economy and for different sectors. Most sectors experienced positive productivity growth, with the exception of the mining and oil and gas extraction sector (its average productivity growth rate was −0.36%). The negative growth in that sector may be caused by the fact that these industries are capital-intensive industries and the cost of extracting these resources is high and rising.

On the other hand, the information and cultural industries sector led the country’s labour productivity growth. In the past few decades, there have been dramatic innovations in these industries with the widespread use of cheap powerful computers and other new technologies. The agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting sector came in second in terms of this metric, experiencing a 3% productivity growth; the surge in the sector’s productivity growth is partly due to higher world prices of agricultural products that encourage more investment in the industry, and to the availability of better and improved seeds and planting, maintenance, and harvest techniques. The wholesale trade sector came in third, with an average annual growth rate in productivity of 2.79% over these four decades. Better logistics is the primary reason for the surge in this sector’s productivity. Firms like Loblaws and Walmart have figured out how to better use computers to track their inventories (for instance, by using bar-code scanners) and place product orders automatically with their suppliers. These practices gave them a huge advantage over the competitors who failed to innovate—and over previous versions of themselves. Seeing their success, other firms followed in their footsteps, which spread productivity gains to the entire sector and even the economy as a whole.

Thus, we have learned several things from what happened in the past four decades. An economy can enjoy higher productivity in different ways—such as by developing new technologies and equipment (for example, in the case of the information and cultural sector) or by improving existing techniques (as in the lumber and agricultural sector).

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 9.15

In this chapter, we described several sources of productivity growth. Which of these sources correspond to the growth in the information and cultural industries sector, in the agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting sector, and in the wholesale trade sector?

Question 9.16

How does our description of what happened in the wholesale trade sector tie in with the New Growth Theory?