Price Indexes and the Aggregate Price Level

In the spring and summer of 2011, Americans were facing sticker shock at the gas pump: the price of a gallon of regular gasoline had risen from an average of $1.61 at the end of December 2008 to close to $4. Many other prices were also up. Some prices, though, were heading down: some foods, like eggs, were coming down from a run-

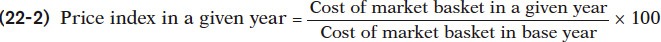

The aggregate price level is a measure of the overall level of prices in the economy.

Clearly, there was a need for a single number summarizing what was happening to consumer prices. Just as macroeconomists find it useful to have a single number representing the overall level of output, they also find it useful to have a single number representing the overall level of prices: the aggregate price level. Yet a huge variety of goods and services are produced and consumed in the economy. How can we summarize the prices of all these goods and services with a single number? The answer lies in the concept of a price index—a concept best introduced with an example.

Market Baskets and Price Indexes

Suppose that a frost in Florida destroys most of the citrus harvest. As a result, the price of an orange rises from $0.20 to $0.40, the price of a grapefruit rises from $0.60 to $1.00, and the price of a lemon rises from $0.25 to $0.45. How much has the price of citrus fruit increased?

One way to answer that question is to state three numbers—

A market basket is a hypothetical set of consumer purchases of goods and services.

To measure average price changes for consumer goods and services, economists track changes in the cost of a typical consumer’s consumption bundle—

Table 22-3 shows the pre-

|

|

Pre- |

Post- |

|---|---|---|

|

Price of orange |

$0.20 |

$0.40 |

|

Price of grapefruit |

0.60 |

1.00 |

|

Price of lemon |

0.25 |

0.45 |

|

Cost of market basket (200 oranges, 50 grapefruit, 100 lemons) |

(200 × $0.20) + (50 × $0.60) + (100 × $0.25) = $95.00 |

(200 × $0.40) + (50 × $1.00) + (100 × $0.45) = $175.00 |

TABLE 7-

Economists use the same method to measure changes in the overall price level: they track changes in the cost of buying a given market basket. In addition, they perform another simplification in order to avoid having to keep track of the information that the market basket cost—

A price index measures the cost of purchasing a given market basket in a given year, where that cost is normalized so that it is equal to 100 in the selected base year.

In our example, the citrus fruit market basket cost $95 in the base year, the year before the frost. So by Equation 22-

Thus, the price index makes it clear that the average price of citrus has risen 84.2% as a consequence of the frost. Because of its simplicity and intuitive appeal, the method we’ve just described is used to calculate a variety of price indexes to track average price changes among a variety of different groups of goods and services. For example, the consumer price index, which we’ll discuss shortly, is the most widely used measure of the aggregate price level, the overall price level of final consumer goods and services across the economy.

The inflation rate is the percent change per year in a price index—

Price indexes are also the basis for measuring inflation. The inflation rate is the annual percent change in an official price index. The inflation rate from year 1 to year 2 is calculated using the following formula, where we assume that year 1 and year 2 are consecutive years.

Typically, a news report that cites “the inflation rate” is referring to the annual percent change in the consumer price index.

The Consumer Price Index

The consumer price index, or CPI, measures the cost of the market basket of a typical urban American family.

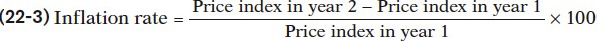

The most widely used measure of prices in the United States is the consumer price index (often referred to simply as the CPI), which is intended to show how the cost of all purchases by a typical urban family has changed over time. It is calculated by surveying market prices for a market basket that is constructed to represent the consumption of a typical family of four living in a typical American city. The base period for the index is currently 1982–

The market basket used to calculate the CPI is far more complex than the three-

Figure 22-5 shows the weight of major categories in the consumer price index as of December 2010. For example, motor fuel, mainly gasoline, accounted for 5% of the CPI in December 2010. So when gas prices rose nearly 150%, from about $1.61 a gallon in late 2008 to $3.96 a gallon in May 2011, the effect was to increase the CPI by about 1.5 times 5%—that is, around 7.5%.

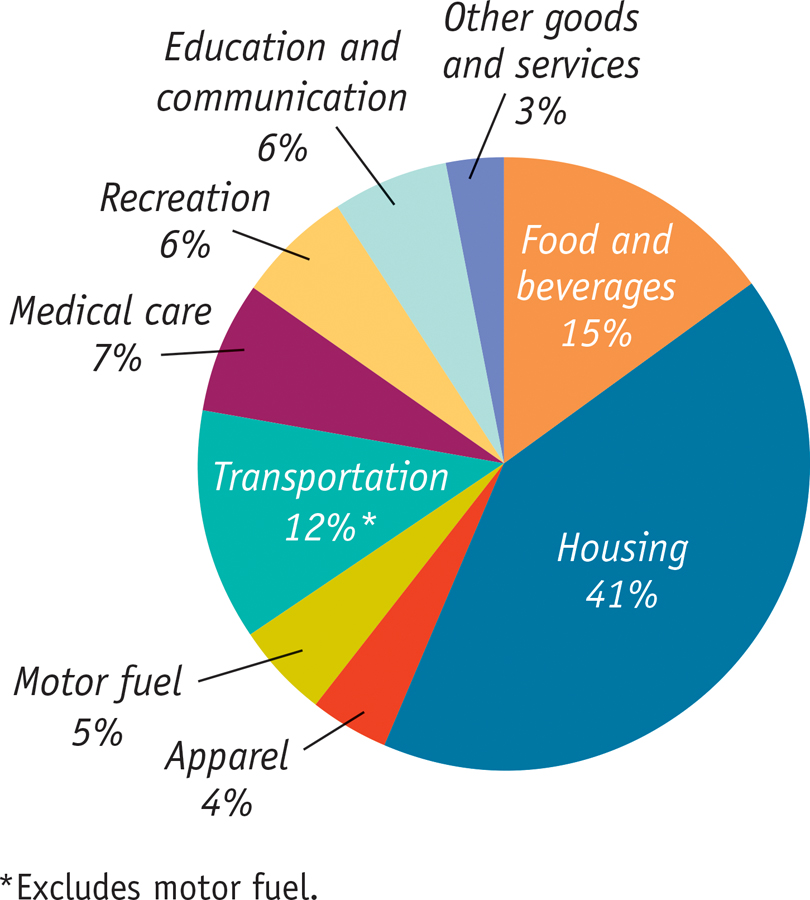

Figure 22-6 shows how the CPI has changed since measurement began in 1913. Since 1940, the CPI has risen steadily, although its annual percent increases in recent years have been much smaller than those of the 1970s and early 1980s. (A logarithmic scale is used so that equal percent changes in the CPI have the same slope.)

The United States is not the only country that calculates a consumer price index. In fact, nearly every country has one. As you might expect, the market baskets that make up these indexes differ quite a lot from country to country. In poor countries, where people must spend a high proportion of their income just to feed themselves, food makes up a large share of the price index. Among high-

Other Price Measures

The producer price index, or PPI, measures changes in the prices of goods purchased by producers.

There are two other price measures that are also widely used to track economy-

The GDP deflator for a given year is 100 times the ratio of nominal GDP to real GDP in that year.

The other widely used price measure is the GDP deflator; it isn’t exactly a price index, although it serves the same purpose. Recall how we distinguished between nominal GDP (GDP in current prices) and real GDP (GDP calculated using the prices of a base year). The GDP deflator for a given year is equal to 100 times the ratio of nominal GDP for that year to real GDP for that year. Since real GDP is currently expressed in 2005 dollars, the GDP deflator for 2005 is equal to 100. If nominal GDP doubles but real GDP does not change, the GDP deflator indicates that the aggregate price level doubled.

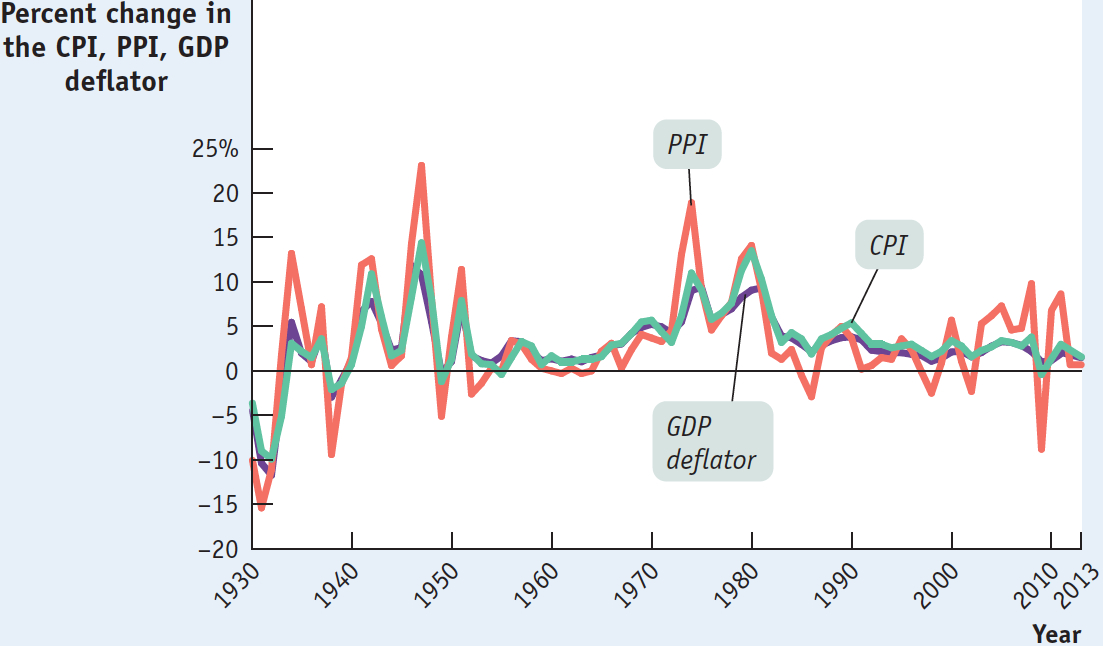

Perhaps the most important point about the different inflation rates generated by these three measures of prices is that they usually move closely together (although the producer price index tends to fluctuate more than either of the other two measures). Figure 22-7 shows the annual percent changes in the three indexes since 1930. By all three measures, the U.S. economy experienced deflation during the early years of the Great Depression, inflation during World War II, accelerating inflation during the 1970s, and a return to relative price stability in the 1990s. Notice, by the way, the dramatic ups and downs in producer prices from 2000 to 2013 on the graph; this reflects large swings in energy and food prices, which play a much bigger role in the PPI than they do in either the CPI or the GDP deflator.

ECONOMICS in Action: Indexing to the CPI

Indexing to the CPI

Although GDP is a very important number for shaping economic policy, official statistics on GDP don’t have a direct effect on people’s lives. The CPI, by contrast, has a direct and immediate impact on millions of Americans.

The reason is that many payments are tied, or “indexed,” to the CPI—

The practice of indexing payments to consumer prices goes back to the dawn of the United States as a nation. In 1780 the Massachusetts State Legislature recognized that the pay of its soldiers fighting the British needed to be increased because of inflation that occurred during the Revolutionary War. The legislature adopted a formula that made a soldier’s pay proportional to the cost of a market basket, consisting of 5 bushels of corn,  pounds of beef, 10 pounds of sheep’s wool, and 16 pounds of shoe leather.

pounds of beef, 10 pounds of sheep’s wool, and 16 pounds of shoe leather.

Today, 54 million people receive payments from Social Security, a national retirement program that accounts for almost a quarter of current total federal spending—

Other government payments are also indexed to the CPI. In addition, income tax brackets, the bands of income levels that determine a taxpayer’s income tax rate, are also indexed to the CPI. (An individual in a higher income bracket pays a higher income tax rate in a progressive tax system like ours.) Indexing also extends to the private sector, where many private contracts, including some wage settlements, contain cost-

Because the CPI plays such an important and direct role in people’s lives, it’s a politically sensitive number. The Bureau of Labor Statistics, which calculates the CPI, takes great care in collecting and interpreting price and consumption data. It uses a complex method in which households are surveyed to determine what they buy and where they shop, and a carefully selected sample of stores are surveyed to get representative prices.

Quick Review

Changes in the aggregate price level are measured by the cost of buying a particular market basket during different years. A price index for a given year is the cost of the market basket in that year normalized so that the price index equals 100 in a selected base year.

The inflation rate is calculated as the percent change in a price index. The most commonly used price index is the consumer price index, or CPI, which tracks the cost of a basket of consumer goods and services. The producer price index, or PPI, does the same for goods and services used as inputs by firms. The GDP deflator measures the aggregate price level as the ratio of nominal to real GDP times 100. These three measures normally behave quite similarly.

22-3

Question 7.6

Consider Table 22-3 but suppose that the market basket is composed of 100 oranges, 50 grapefruit, and 200 lemons. How does this change the pre-

frost and post- frost price indexes? Explain. Generalize your explanation to how the construction of the market basket affects the price index. Question 7.7

For each of the following events, how would an economist using a 10-

year- old market basket create a bias in measuring the change in the cost of living today? A typical family owns more cars than it would have a decade ago. Over that time, the average price of a car has increased more than the average prices of other goods.

Virtually no households had broadband internet access a decade ago. Now many households have it, and the price has regularly fallen each year.

Question 7.8

The consumer price index in the United States (base period 1982–

1984) was 226.229 in 2012 and 229.324 in 2013. Calculate the inflation rate from 2012 to 2013.

Solutions appear at back of book.

Getting a Jump on GDP

GDP matters. Investors and business leaders are always anxious to get the latest numbers. When the Bureau of Economic Analysis releases its first estimate of each quarter’s GDP, normally on the 27th or 28th day of the month after the quarter ends, it’s invariably a big news story.

In fact, many companies and other players in the economy are so eager to know what’s happening to GDP that they don’t want to wait for the official estimate. So a number of organizations produce numbers that can be used to predict what the official GDP number will say. Let’s talk about two of those organizations, the economic consulting firm Macroeconomic Advisers and the nonprofit Institute of Supply Management.

Macroeconomic Advisers takes a direct approach: it produces its own estimates of GDP based on raw data from the U.S. government. But whereas the Bureau of Economic Analysis estimates GDP only on a quarterly basis, Macroeconomic Advisers produces monthly estimates. This means that clients can, for example, look at the estimates for January and February and make a pretty good guess at what first-

The Institute for Supply Management (ISM) takes a very different approach. It relies on monthly surveys of purchasing managers—

Responses to the surveys are released in the form of indexes showing the percentage of companies that are expanding. Obviously, these indexes don’t directly tell you what is happening to GDP. But historically, the ISM indexes have been strongly correlated with the rate of growth of GDP, and this historical relationship can be used to translate ISM data into “early warning” GDP estimates.

So if you just can’t wait for those quarterly GDP numbers, you’re not alone. The private sector has responded to demand, and you can get your data fix every month.

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 7.9

I9R2EzuyklnMWG1YmIM4qgaOH+yN0t+aSRGjFOIqo4fTnfSU9ayUcHE4EbEN7X6Cx+AIg/HlZpL9JHHLXg8LAi6AD+BrsquA1+LSl3EglNTdKfC13stmVg==Why do businesses care about GDP to such an extent that they want early estimates?Question 7.10

nn8UWjKlIOHzHGrOM7YNyNqaL8XvjETOT4qgcA8hqJiGeI56Vh0/5ehVK8CWVxVkzDj/rhFgNX72xyZdE2IFZnQ9F9riPl81AXFL19uljPsJq7jSP2eCdrXdGwM+Bji3MVuMVWYhox6Ha7XRWc4Nf8AQpfEtPbyTSBO9C9VQbthf4ICQcIa8gu1WLtA=How do the methods of Macroeconomic Advisers and the Institute for Supply Management fit into the three different ways to calculate GDP?Question 7.11

+OtjHB9faqjpf6sYzfKrNsjLviVtfVj9m0dG5d8DlS2r4075HDrMJObYtbqUlWl7p12uCiP9NzTwbls/YfmM7pfi2pBZuUxzi023gPPoGChRpg9zFjVKQ60WABTOMKSLimivsw==If private firms are producing GDP estimates, why do we need the Bureau of Economic Analysis?