Comparing Economies Across Time and Space

Before we analyze the sources of long-

Real GDP per Capita

The key statistic used to track economic growth is real GDP per capita—

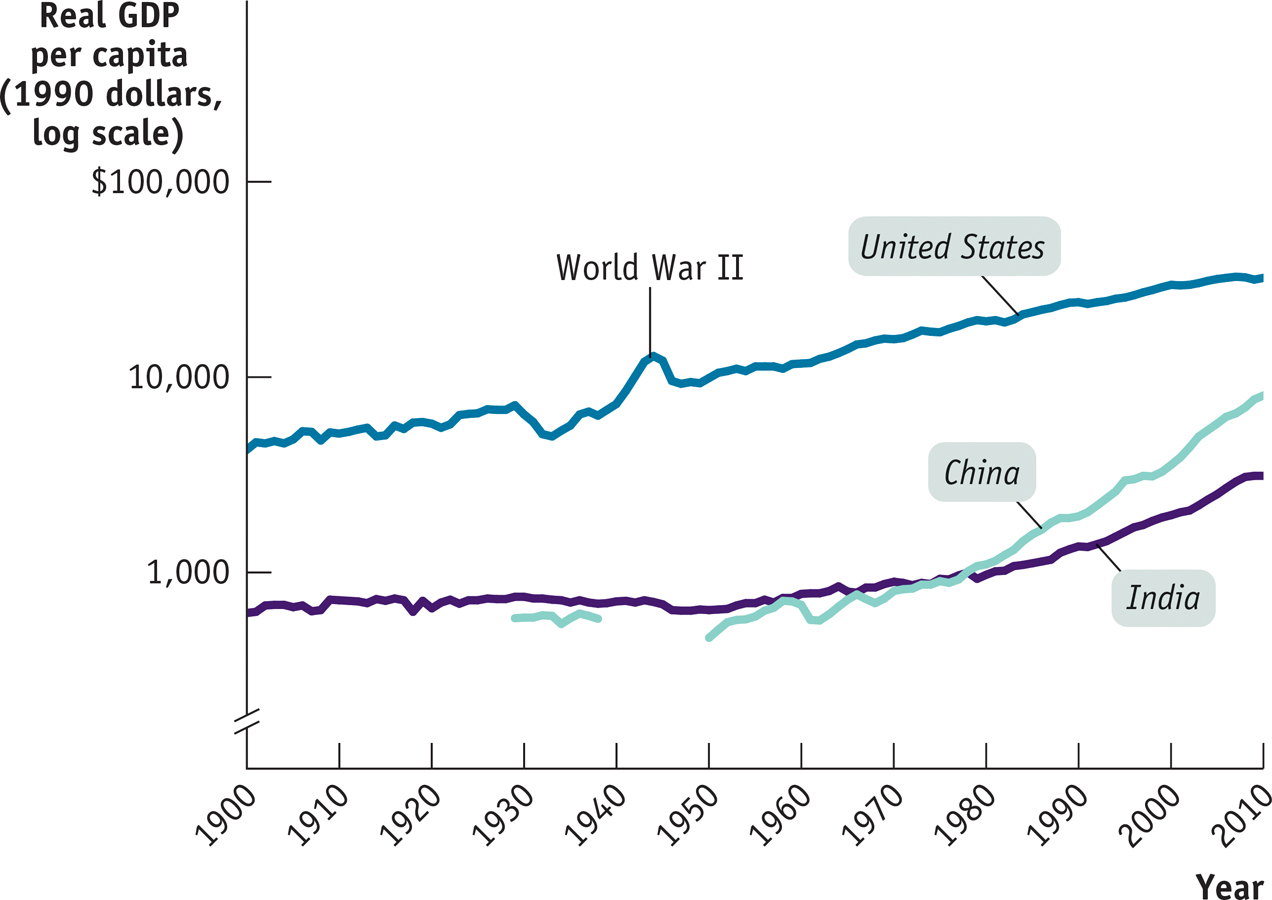

Although we also learned in Chapter 7 that growth in real GDP per capita should not be a policy goal in and of itself, it does serve as a very useful summary measure of a country’s economic progress over time. Figure 24-1 shows real GDP per capita for the United States, India, and China, measured in 1990 dollars, from 1900 to 2010. (We’ll talk about India and China in a moment.) The vertical axis is drawn on a logarithmic scale so that equal percent changes in real GDP per capita across countries are the same size in the graph.

To give a sense of how much the U.S. economy grew during the last century, Table 24-1 shows real GDP per capita at selected years, expressed two ways: as a percentage of the 1900 level and as a percentage of the 2010 level. In 1920, the U.S. economy already produced 136% as much per person as it did in 1900. In 2010, it produced 758% as much per person as it did in 1900, an almost eightfold increase. Alternatively, in 1900 the U.S. economy produced only 13% as much per person as it did in 2010.

|

Year |

Percentage of 1900 real GDP per capita |

Percentage of 2010 real GDP per capita |

|---|---|---|

|

1900 |

100% |

13% |

|

1920 |

136 |

18 |

|

1940 |

171 |

23 |

|

1980 |

454 |

60 |

|

2000 |

696 |

92 |

|

2010 |

758 |

100 |

|

Sources: Angus Maddison, Statistics on World Population, GDP, and Per Capita GDP, 1– |

||

TABLE 9-

The income of the typical family normally grows more or less in proportion to per capita income. For example, a 1% increase in real GDP per capita corresponds, roughly, to a 1% increase in the income of the median or typical family—

Yet many people in the world have a standard of living equal to or lower than that of the United States at the beginning of the last century. That’s the message about China and India in Figure 24-1: despite dramatic economic growth in China over the last three decades and the less dramatic acceleration of economic growth in India, China has only recently exceeded the standard of living that the United States enjoyed in the early twentieth century, while India is still poorer than the United States was at that time. And much of the world today is poorer than China or India.

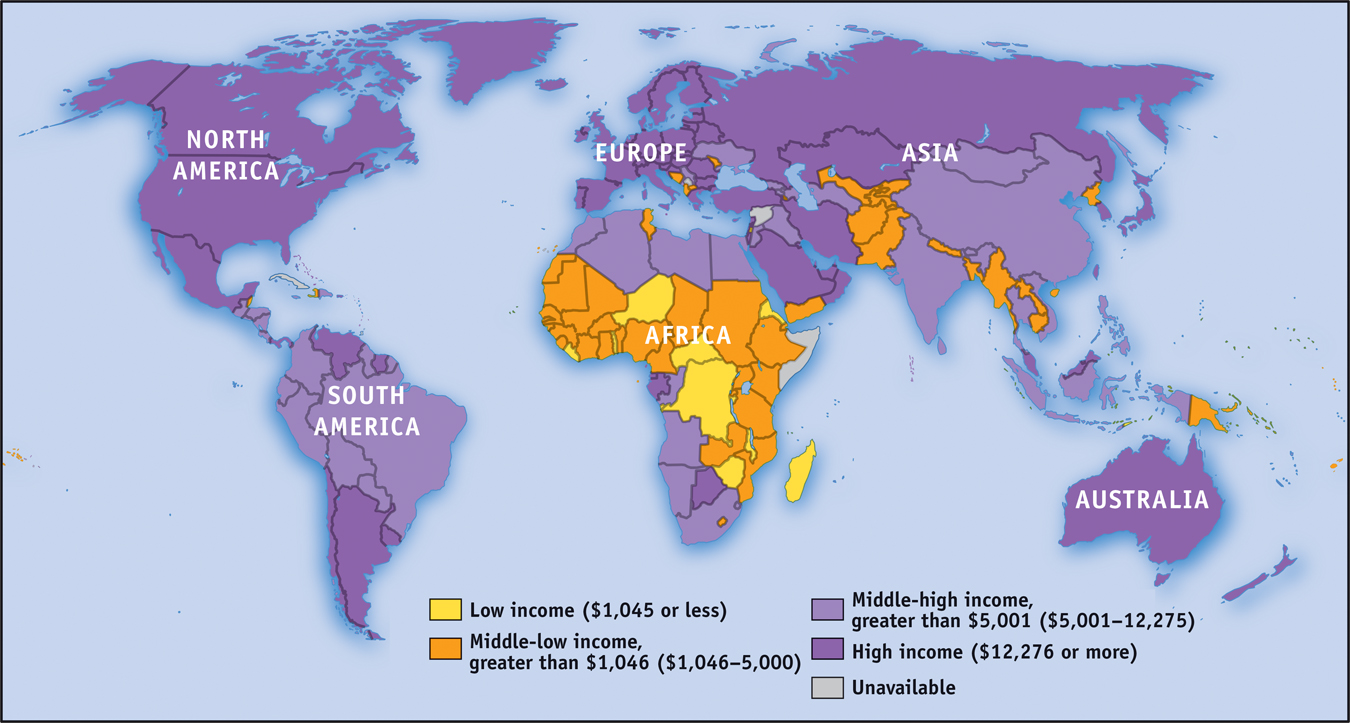

You can get a sense of how poor much of the world remains by looking at Figure 24-2, a map of the world in which countries are classified according to their 2013 levels of GDP per capita, in U.S. dollars. As you can see, large parts of the world have very low incomes. Generally speaking, the countries of Europe and North America, as well as a few in the Pacific, have high incomes. The rest of the world, containing most of its population, is dominated by countries with GDP less than $5,000 per capita—

PITFALLS: CHANGE IN LEVELS VERSUS RATE OF CHANGE

CHANGE IN LEVELS VERSUS RATE OF CHANGE

When studying economic growth, it’s vitally important to understand the difference between a change in level and a rate of change. When we say that real GDP “grew,” we mean that the level of real GDP increased. For example, we might say that U.S. real GDP grew during 2013 by $297 billion.

If we knew the level of U.S. real GDP in 2012, we could also represent the amount of 2013 growth in terms of a rate of change. For example, if U.S. real GDP in 2012 had been $15,470 billion, then U.S. real GDP in 2013 would have been $15,470 billion + $297 billion = $15,767 billion. We could calculate the rate of change, or the growth rate, of U.S. real GDP during 2013 as: (($15,767 billion − $15,470 billion)/$15,470 billion) × 100 = $297 billion/$15,470 billion) × 100 = 1.92%. Statements about economic growth over a period of years almost always refer to changes in the growth rate.

When talking about growth or growth rates, economists often use phrases that appear to mix the two concepts and so can be confusing. For example, when we say that “U.S. growth fell during the 1970s,” we are really saying that the U.S. growth rate of real GDP was lower in the 1970s in comparison to the 1960s. When we say that “growth accelerated during the early 1990s,” we are saying that the growth rate increased year after year in the early 1990s—

Growth Rates

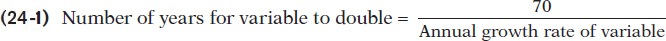

According to the Rule of 70, the time it takes a variable that grows gradually over time to double is approximately 70 divided by that variable’s annual growth rate.

How did the United States manage to produce over eight times as much per person in 2013 than in 1900? A little bit at a time. Long-

To have a sense of the relationship between the annual growth rate of real GDP per capita and the long-

(Note that the Rule of 70 can only be applied to a positive growth rate.) So if real GDP per capita grows at 1% per year, it will take 70 years to double. If it grows at 2% per year, it will take only 35 years to double. In fact, U.S. real GDP per capita rose on average 1.9% per year over the last century.

Applying the Rule of 70 to this information implies that it should have taken 37 years for real GDP per capita to double; it would have taken 111 years—

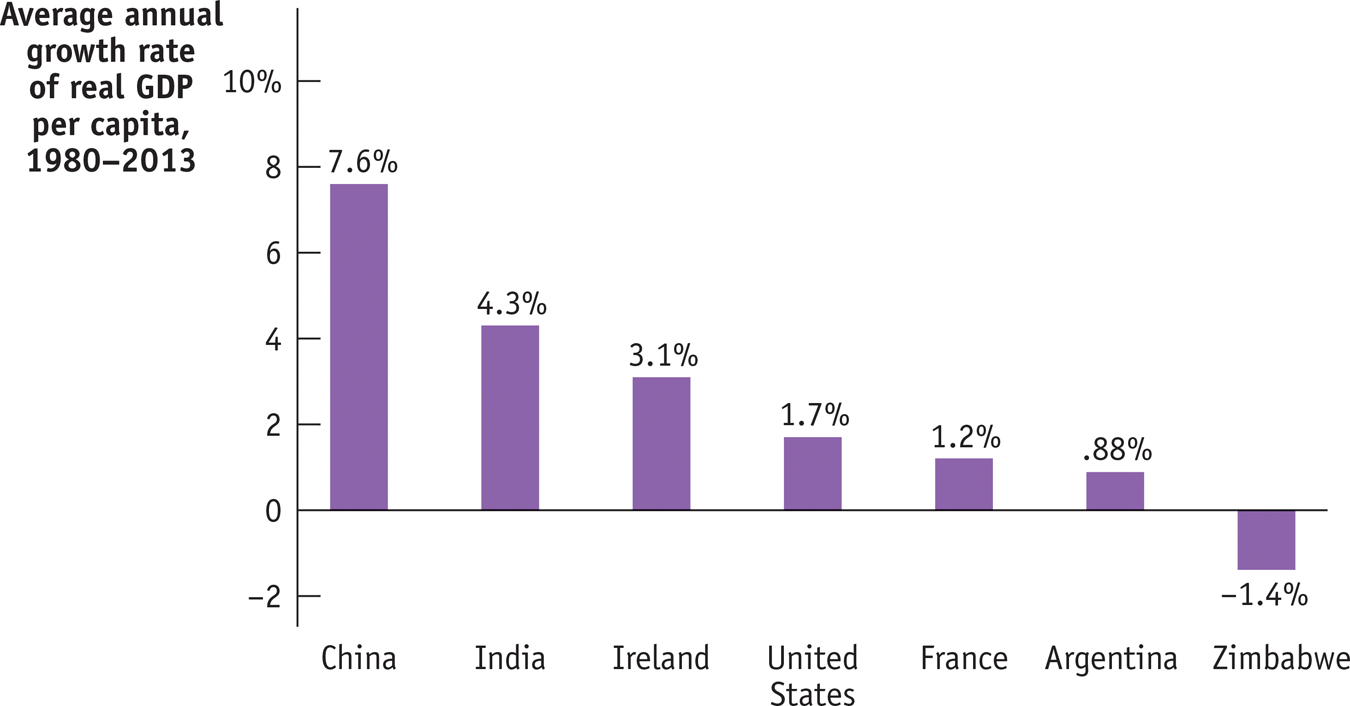

Figure 24-3 shows the average annual rate of growth of real GDP per capita for selected countries from 1980 to 2013. Some countries were notable success stories: for example, China, though still quite poor, has made spectacular progress. India, although not matching China’s performance, has also achieved impressive growth, as discussed in the following Economics in Action.

Some countries, though, have had very disappointing growth. Argentina was once considered a wealthy nation. In the early years of the twentieth century, it was in the same league as the United States and Canada. But since then it has lagged far behind more dynamic economies. And still others, like Zimbabwe, have slid backward.

What explains these differences in growth rates? To answer that question, we need to examine the sources of long-

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: India Takes Off

India Takes Off

India achieved independence from Great Britain in 1947, becoming the world’s most populous democracy—

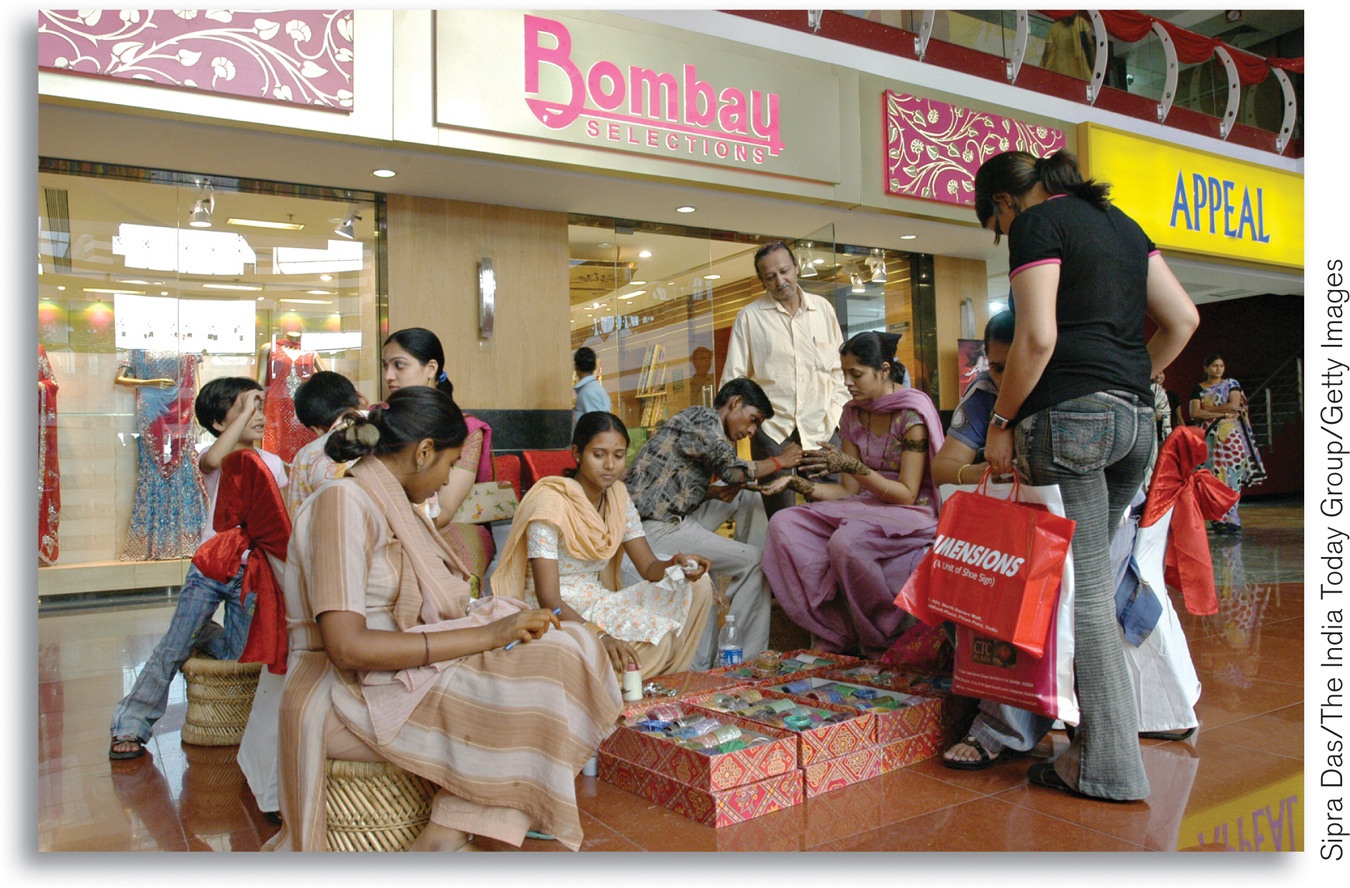

Since then, however, India has done much better. As Figure 24-3 shows, real GDP per capita has grown at an average rate of 4.3% a year, more than tripling between 1980 and 2013. India now has a large and rapidly growing middle class.

What went right in India after 1980? Many economists point to policy reforms. For decades after independence, India had a tightly controlled, highly regulated economy. Today, things are very different: a series of reforms opened the economy to international trade and freed up domestic competition. Some economists, however, argue that this can’t be the main story because the big policy reforms weren’t adopted until 1991, yet growth accelerated around 1980.

Regardless of the explanation, India’s economic rise has transformed it into a major new economic power—

The big question now is whether this growth can continue. Skeptics argue that there are important bottlenecks in the Indian economy that may constrain future growth. They point in particular to the still low education level of much of India’s population and inadequate infrastructure—

Quick Review

Economic growth is measured using real GDP per capita.

In the United States, real GDP per capita increased eightfold since 1900, resulting in a large increase in living standards.

Many countries have real GDP per capita much lower than that of the United States. More than half of the world’s population has living standards worse than those existing in the United States in the early 1900s.

The long-

term rise in real GDP per capita is the result of gradual growth. The Rule of 70 tells us how many years at a given annual rate of growth it takes to double real GDP per capita. Growth rates of real GDP per capita differ substantially among nations.

24-1

Question 9.1

Why do economists use real GDP per capita to measure economic progress rather than some other measure, such as nominal GDP per capita or real GDP?

Question 9.2

Apply the Rule of 70 to the data in Figure 24-3 to determine how long it will take each of the countries listed there (except Zimbabwe) to double its real GDP per capita. Would India’s real GDP per capita exceed that of the United States in the future if growth rates remain as shown in Figure 24-3? Why or why not?

Question 9.3

Although China and India currently have growth rates much higher than the U.S. growth rate, the typical Chinese or Indian household is far poorer than the typical American household. Explain why.

Solutions appear at back of book.