Aggregate Supply

Between 1929 and 1933, there was a sharp fall in aggregate demand—a reduction in the quantity of goods and services demanded at any given price level. One consequence of the economy-wide decline in demand was a fall in the prices of most goods and services. By 1933, the GDP deflator (one of the price indexes we defined in Chapter 22) was 26% below its 1929 level, and other indexes were down by similar amounts. A second consequence was a decline in the output of most goods and services: by 1933, real GDP was 27% below its 1929 level. A third consequence, closely tied to the fall in real GDP, was a surge in the unemployment rate from 3% to 25%.

The aggregate supply curve shows the relationship between the aggregate price level and the quantity of aggregate output supplied in the economy.

The association between the plunge in real GDP and the plunge in prices wasn’t an accident. Between 1929 and 1933, the U.S. economy was moving down its aggregate supply curve, which shows the relationship between the economy’s aggregate price level (the overall price level of final goods and services in the economy) and the total quantity of final goods and services, or aggregate output, producers are willing to supply. (As you will recall, we use real GDP to measure aggregate output. So we’ll often use the two terms interchangeably.) More specifically, between 1929 and 1933 the U.S. economy moved down its short-run aggregate supply curve.

The Short-Run Aggregate Supply Curve

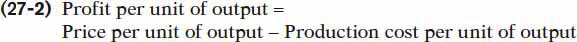

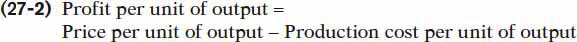

The period from 1929 to 1933 demonstrated that there is a positive relationship in the short run between the aggregate price level and the quantity of aggregate output supplied. That is, a rise in the aggregate price level is associated with a rise in the quantity of aggregate output supplied, other things equal; a fall in the aggregate price level is associated with a fall in the quantity of aggregate output supplied, other things equal. To understand why this positive relationship exists, consider the most basic question facing a producer: is producing a unit of output profitable or not? Let’s define profit per unit:

Thus, the answer to the question depends on whether the price the producer receives for a unit of output is greater or less than the cost of producing that unit of output. At any given point in time, many of the costs producers face are fixed per unit of output and can’t be changed for an extended period of time. Typically, the largest source of inflexible production cost is the wages paid to workers. Wages here refers to all forms of worker compensation, such as employer-paid health care and retirement benefits in addition to earnings.

The nominal wage is the dollar amount of the wage paid.

Wages are typically an inflexible production cost because the dollar amount of any given wage paid, called the nominal wage, is often determined by contracts that were signed some time ago. And even when there are no formal contracts, there are often informal agreements between management and workers, making companies reluctant to change wages in response to economic conditions. For example, companies usually will not reduce wages during poor economic times—unless the downturn has been particularly long and severe—for fear of generating worker resentment. Correspondingly, they typically won’t raise wages during better economic times—until they are at risk of losing workers to competitors—because they don’t want to encourage workers to routinely demand higher wages.

Sticky wages are nominal wages that are slow to fall even in the face of high unemployment and slow to rise even in the face of labor shortages.

As a result of both formal and informal agreements, then, the economy is characterized by sticky wages: nominal wages that are slow to fall even in the face of high unemployment and slow to rise even in the face of labor shortages. It’s important to note, however, that nominal wages cannot be sticky forever: ultimately, formal contracts and informal agreements will be renegotiated to take into account changed economic circumstances. As the Pitfalls at the end of this section explains, how long it takes for nominal wages to become flexible is an integral component of what distinguishes the short run from the long run.

To understand how the fact that many costs are fixed in nominal terms gives rise to an upward-sloping short-run aggregate supply curve, it’s helpful to know that prices are set somewhat differently in different kinds of markets. In perfectly competitive markets, producers take prices as given; in imperfectly competitive markets, producers have some ability to choose the prices they charge. In both kinds of markets, there is a short-run positive relationship between prices and output, but for slightly different reasons.

Let’s start with the behavior of producers in perfectly competitive markets; remember, they take the price as given. Imagine that, for some reason, the aggregate price level falls, which means that the price received by the typical producer of a final good or service falls. Because many production costs are fixed in the short run, production cost per unit of output doesn’t fall by the same proportion as the fall in the price of output. So the profit per unit of output declines, leading perfectly competitive producers to reduce the quantity supplied in the short run.

On the other hand, suppose that for some reason the aggregate price level rises. As a result, the typical producer receives a higher price for its final good or service. Again, many production costs are fixed in the short run, so production cost per unit of output doesn’t rise by the same proportion as the rise in the price of a unit. And since the typical perfectly competitive producer takes the price as given, profit per unit of output rises and output increases.

Now consider an imperfectly competitive producer that is able to set its own price. If there is a rise in the demand for this producer’s product, it will be able to sell more at any given price. Given stronger demand for its products, it will probably choose to increase its prices as well as its output, as a way of increasing profit per unit of output. In fact, industry analysts often talk about variations in an industry’s “pricing power”: when demand is strong, firms with pricing power are able to raise prices—and they do.

Conversely, if there is a fall in demand, firms will normally try to limit the fall in their sales by cutting prices.

The short-run aggregate supply curve shows the relationship between the aggregate price level and the quantity of aggregate output supplied that exists in the short run, the time period when many production costs can be taken as fixed.

Both the responses of firms in perfectly competitive industries and those of firms in imperfectly competitive industries lead to an upward-sloping relationship between aggregate output and the aggregate price level. The positive relationship between the aggregate price level and the quantity of aggregate output producers are willing to supply during the time period when many production costs, particularly nominal wages, can be taken as fixed is illustrated by the short-run aggregate supply curve. The positive relationship between the aggregate price level and aggregate output in the short run gives the short-run aggregate supply curve its upward slope.

Figure 27-5 shows a hypothetical short-run aggregate supply curve, SRAS, which matches actual U.S. data for 1929 and 1933. On the horizontal axis is aggregate output (or, equivalently, real GDP)—the total quantity of final goods and services supplied in the economy—measured in 2009 dollars. On the vertical axis is the aggregate price level as measured by the GDP deflator, with the value for the year 2009 equal to 100. In 1929, the aggregate price level was 9.9 and real GDP was $1,057 billion. In 1933, the aggregate price level was 7.3 and real GDP was only $778 billion. The movement down the SRAS curve corresponds to the deflation and fall in aggregate output experienced over those years.

The Short-Run Aggregate Supply Curve The short-run aggregate supply curve shows the relationship between the aggregate price level and the quantity of aggregate output supplied in the short run, the period in which many production costs such as nominal wages are fixed. It is upward sloping because a higher aggregate price level leads to higher profit per unit of output and higher aggregate output given fixed nominal wages. Here we show numbers corresponding to the Great Depression, from 1929 to 1933: when deflation occurred and the aggregate price level fell from 9.9 (in 1929) to 7.3 (in 1933), firms responded by reducing the quantity of aggregate output supplied from $1,057 billion to $778 billion measured in 2009 dollars.

FOR INQUIRING MINDS: What’s Truly Flexible, What’s Truly Sticky

Most macroeconomists agree that the basic picture shown in Figure 27-5 is correct: there is, other things equal, a positive short-run relationship between the aggregate price level and aggregate output. But many would argue that the details are a bit more complicated.

So far we’ve stressed a difference in the behavior of the aggregate price level and the behavior of nominal wages. That is, we’ve said that the aggregate price level is flexible but nominal wages are sticky in the short run. Although this assumption is a good way to explain why the short-run aggregate supply curve is upward sloping, empirical data on wages and prices don’t wholly support a sharp distinction between flexible prices of final goods and services and sticky nominal wages.

On one side, some nominal wages are in fact flexible even in the short run because some workers are not covered by a contract or informal agreement with their employers. Since some nominal wages are sticky but others are flexible, we observe that the average nominal wage—the nominal wage averaged over all workers in the economy—falls when there is a steep rise in unemployment. For example, nominal wages fell substantially in the early years of the Great Depression.

On the other side, some prices of final goods and services are sticky rather than flexible. For example, some firms, particularly the makers of luxury or name-brand goods, are reluctant to cut prices even when demand falls. Instead they prefer to cut output even if their profit per unit hasn’t declined.

These complications, as we’ve said, don’t change the basic picture. When the aggregate price level falls, some producers cut output because the nominal wages they pay are sticky. And some producers don’t cut their prices in the face of a falling aggregate price level, preferring instead to reduce their output. In both cases, the positive relationship between the aggregate price level and aggregate output is maintained. So, in the end, the short-run aggregate supply curve is still upward sloping.

Shifts of the Short-Run Aggregate Supply Curve

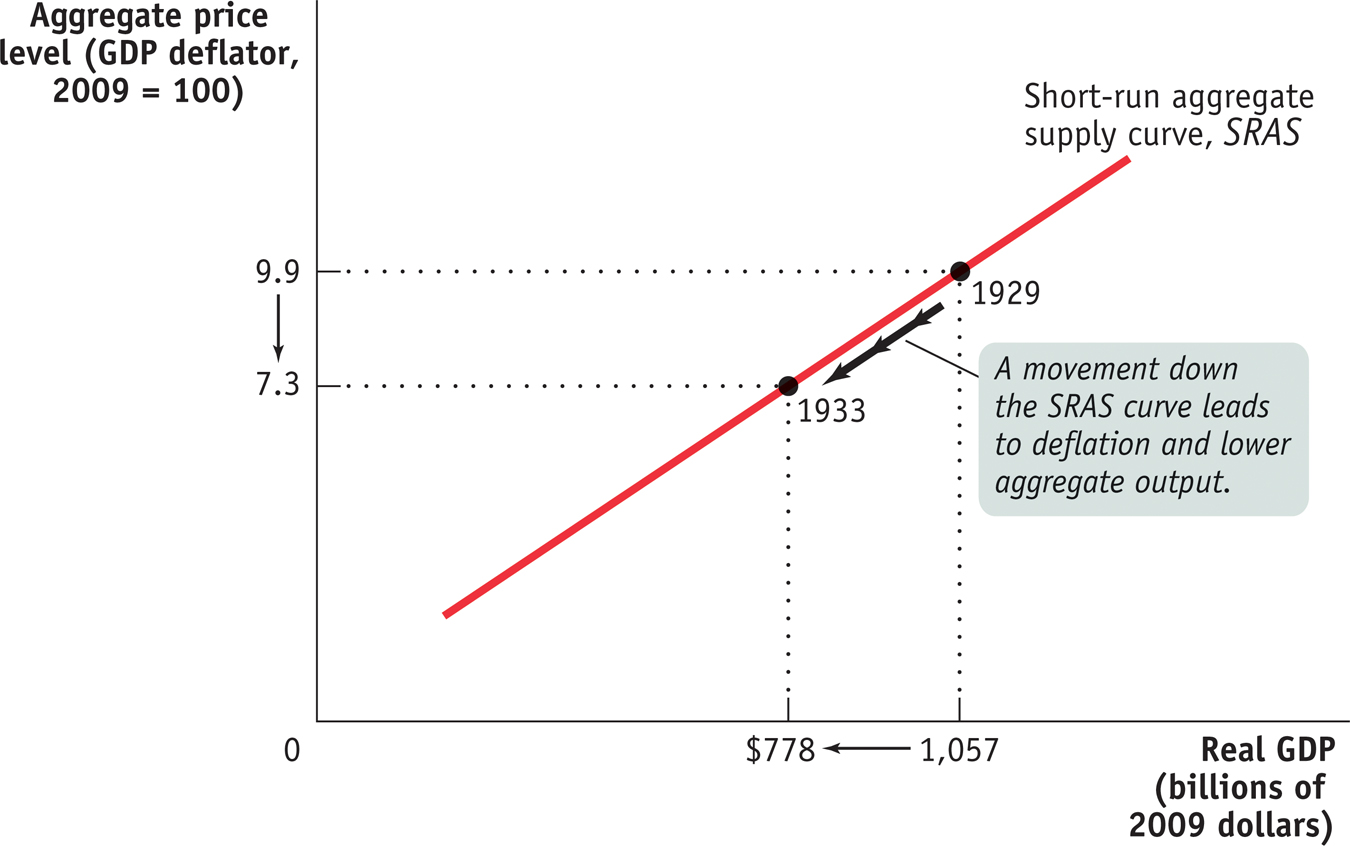

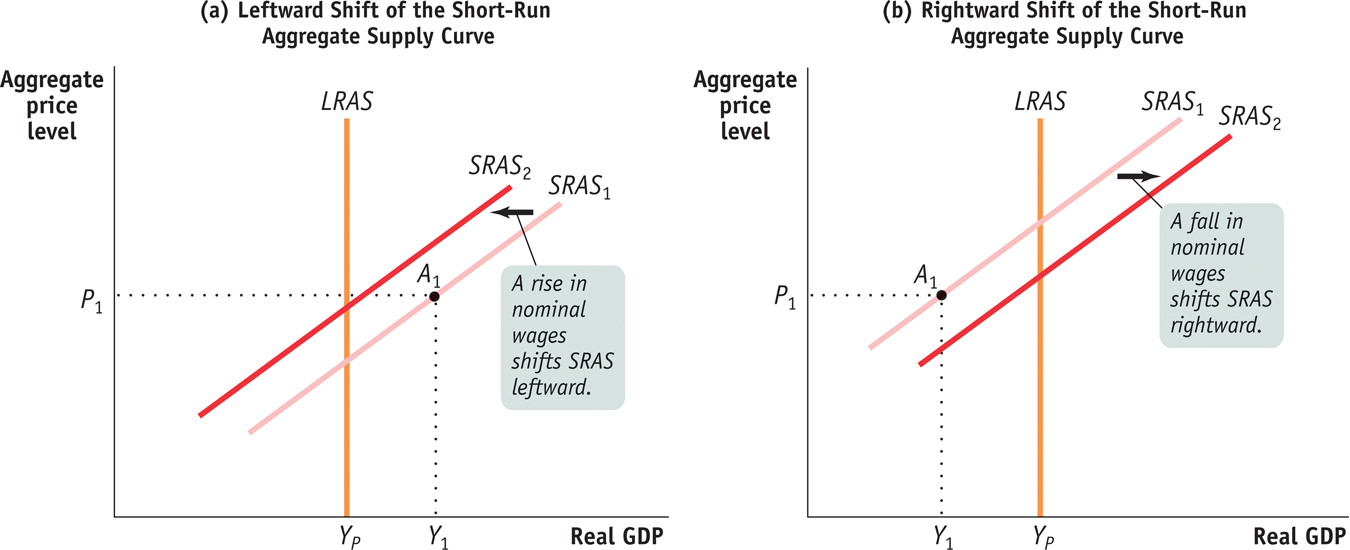

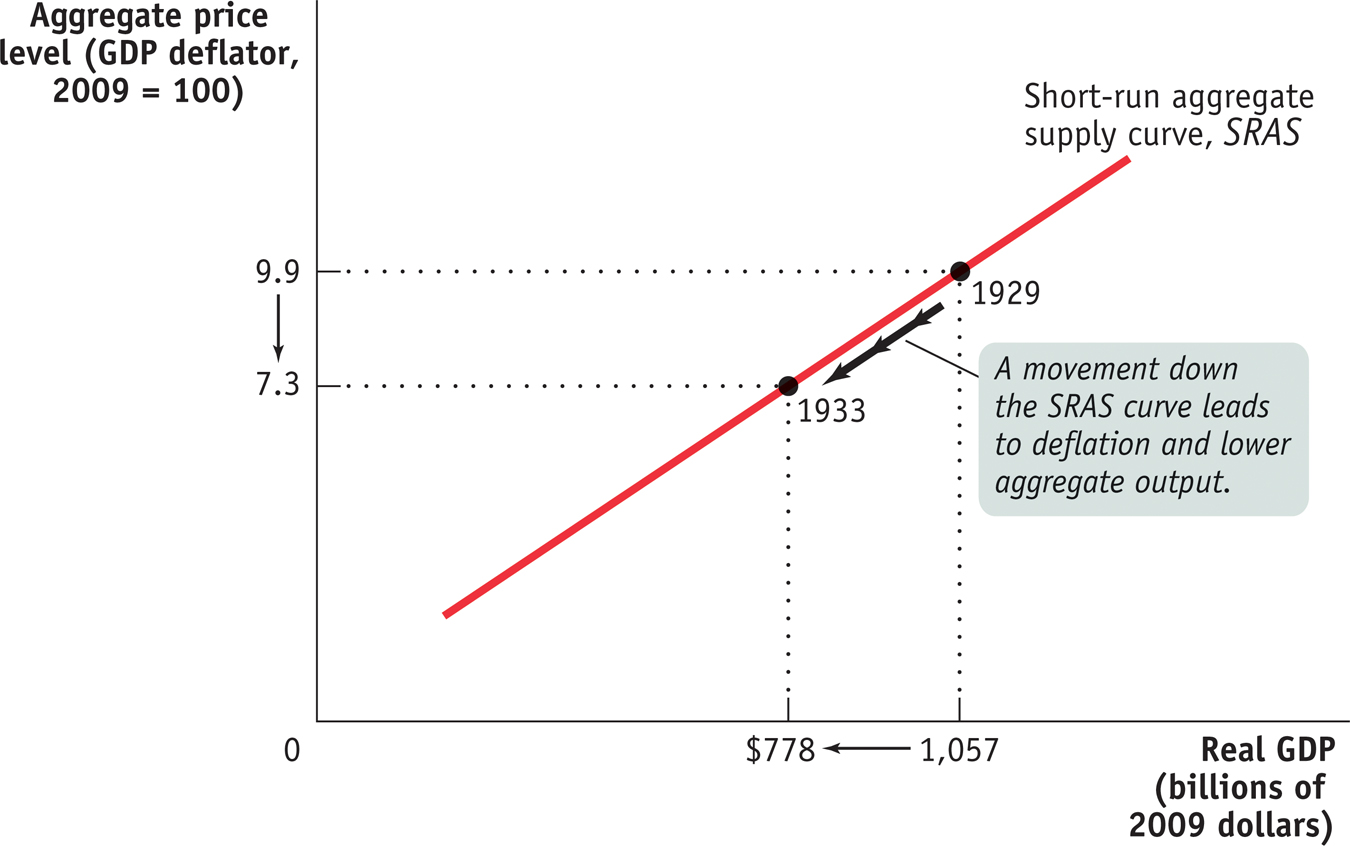

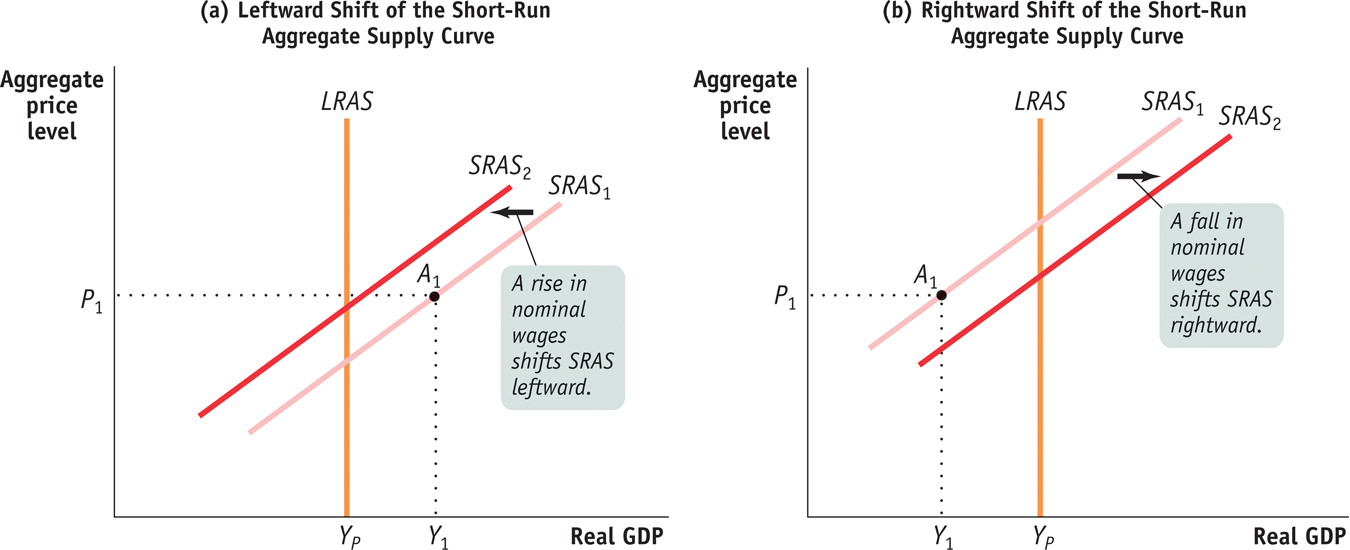

Figure 27-5 shows a movement along the short-run aggregate supply curve, as the aggregate price level and aggregate output fell from 1929 to 1933. But there can also be shifts of the short-run aggregate supply curve, as shown in Figure 27-6. Panel (a) shows a decrease in short-run aggregate supply—a leftward shift of the short-run aggregate supply curve. Aggregate supply decreases when producers reduce the quantity of aggregate output they are willing to supply at any given aggregate price level. Panel (b) shows an increase in short-run aggregate supply—a rightward shift of the short-run aggregate supply curve. Aggregate supply increases when producers increase the quantity of aggregate output they are willing to supply at any given aggregate price level.

Shifts of the Short-Run Aggregate Supply Curve Panel (a) shows a decrease in short-run aggregate supply: the short-run aggregate supply curve shifts leftward from SRAS1 to SRAS2, and the quantity of aggregate output supplied at any given aggregate price level falls. Panel (b) shows an increase in short-run aggregate supply: the short-run aggregate supply curve shifts rightward from SRAS1 to SRAS2, and the quantity of aggregate output supplied at any given aggregate price level rises.

To understand why the short-run aggregate supply curve can shift, it’s important to recall that producers make output decisions based on their profit per unit of output. The short-run aggregate supply curve illustrates the relationship between the aggregate price level and aggregate output: because some production costs are fixed in the short run, a change in the aggregate price level leads to a change in producers’ profit per unit of output and, in turn, leads to a change in aggregate output. But other factors besides the aggregate price level can affect profit per unit and, in turn, aggregate output. It is changes in these other factors that will shift the short-run aggregate supply curve.

To develop some intuition, suppose that something happens that raises production costs—say, an increase in the price of oil. At any given price of output, a producer now earns a smaller profit per unit of output. As a result, producers reduce the quantity supplied at any given aggregate price level, and the short-run aggregate supply curve shifts to the left. If, in contrast, something happens that lowers production costs—say, a fall in the nominal wage—a producer now earns a higher profit per unit of output at any given price of output. This leads producers to increase the quantity of aggregate output supplied at any given aggregate price level, and the short-run aggregate supply curve shifts to the right.

Now we’ll discuss some of the important factors that affect producers’ profit per unit and so can lead to shifts of the short-run aggregate supply curve.

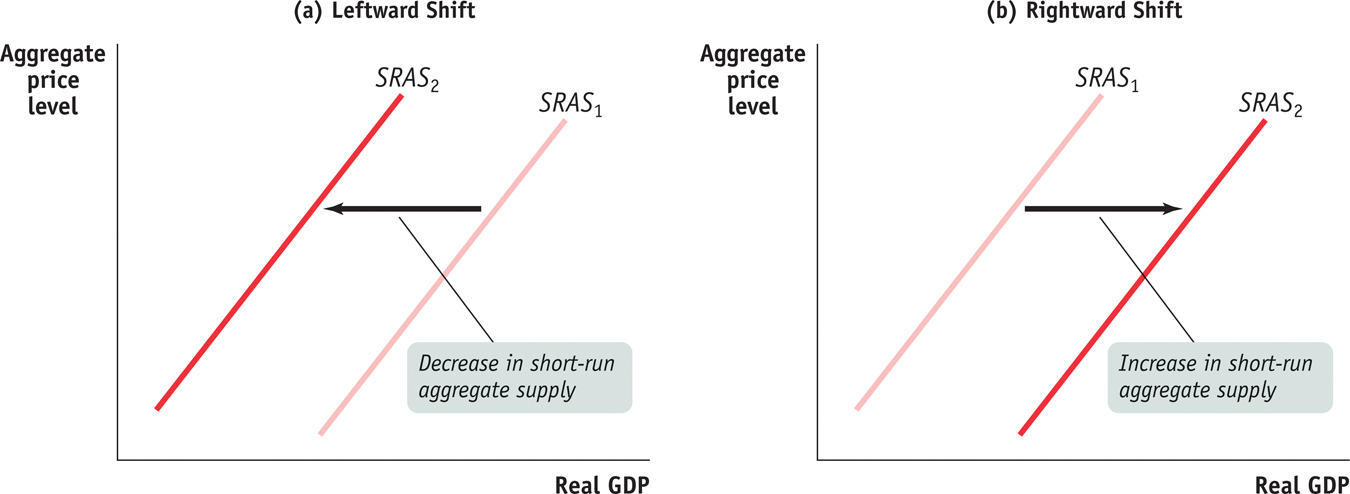

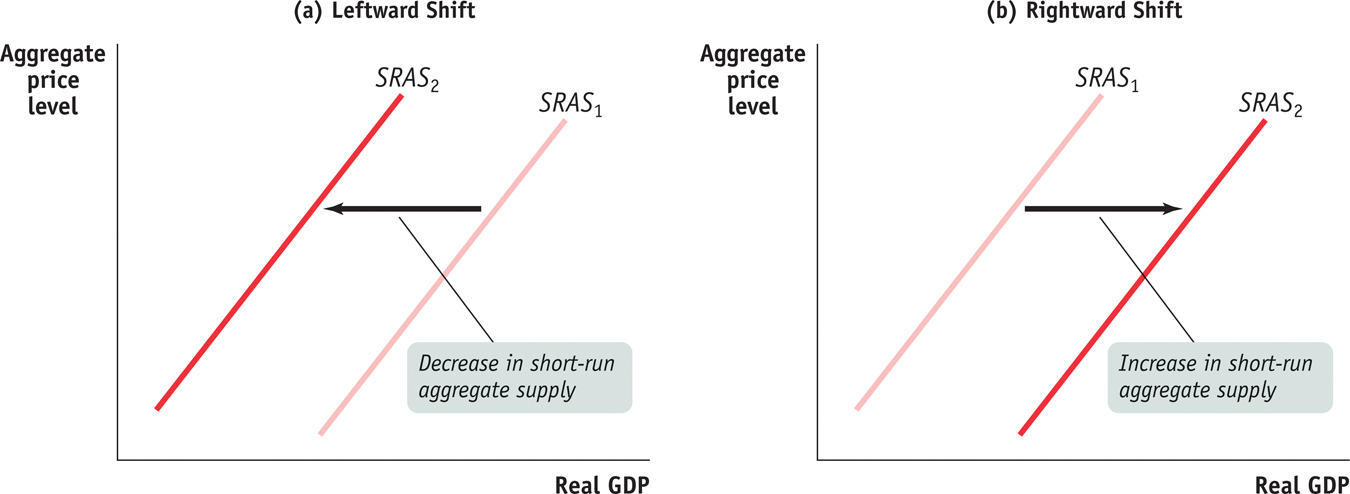

Changes in Commodity Prices In this chapter’s opening story, we described how a surge in the price of oil caused problems for the U.S. economy in the 1970s and early in 2008. Oil is a commodity, a standardized input bought and sold in bulk quantities. An increase in the price of a commodity—oil—raised production costs across the economy and reduced the quantity of aggregate output supplied at any given aggregate price level, shifting the short-run aggregate supply curve to the left. Conversely, a decline in commodity prices reduces production costs, leading to an increase in the quantity supplied at any given aggregate price level and a rightward shift of the short-run aggregate supply curve.

Why isn’t the influence of commodity prices already captured by the short-run aggregate supply curve? Because commodities—unlike, say, soft drinks—are not a final good, their prices are not included in the calculation of the aggregate price level. Further, commodities represent a significant cost of production to most suppliers, just like nominal wages do. So changes in commodity prices have large impacts on production costs. And in contrast to noncommodities, the prices of commodities can sometimes change drastically due to industry-specific shocks to supply—such as wars in the Middle East or rising Chinese demand that leaves less oil for the United States.

Changes in Nominal Wages At any given point in time, the dollar wages of many workers are fixed because they are set by contracts or informal agreements made in the past. Nominal wages can change, however, once enough time has passed for contracts and informal agreements to be renegotiated. Suppose, for example, that there is an economy-wide rise in the cost of health care insurance premiums paid by employers as part of employees’ wages. From the employers’ perspective, this is equivalent to a rise in nominal wages because it is an increase in employer-paid compensation. So this rise in nominal wages increases production costs and shifts the short-run aggregate supply curve to the left. Conversely, suppose there is an economy-wide fall in the cost of such premiums. This is equivalent to a fall in nominal wages from the point of view of employers; it reduces production costs and shifts the short-run aggregate supply curve to the right.

An important historical fact is that during the 1970s the surge in the price of oil had the indirect effect of also raising nominal wages. This “knock-on” effect occurred because many wage contracts included cost-of-living allowances that automatically raised the nominal wage when consumer prices increased. Through this channel, the surge in the price of oil—which led to an increase in overall consumer prices—ultimately caused a rise in nominal wages.

So the economy, in the end, experienced two leftward shifts of the aggregate supply curve: the first generated by the initial surge in the price of oil, the second generated by the induced increase in nominal wages. The negative effect on the economy of rising oil prices was greatly magnified through the cost-of-living allowances in wage contracts. Today, cost-of-living allowances in wage contracts are rare.

Changes in Productivity An increase in productivity means that a worker can produce more units of output with the same quantity of inputs. For example, the introduction of bar-code scanners in retail stores greatly increased the ability of a single worker to stock, inventory, and resupply store shelves. As a result, the cost to a store of “producing” a dollar of sales fell and profit rose. And, correspondingly, the quantity supplied increased. (Think of Walmart and the increase in the number of its stores as an increase in aggregate supply.) So a rise in productivity, whatever the source, increases producers’ profits and shifts the short-run aggregate supply curve to the right.

Conversely, a fall in productivity—say, due to new regulations that require workers to spend more time filling out forms—reduces the number of units of output a worker can produce with the same quantity of inputs. Consequently, the cost per unit of output rises, profit falls, and quantity supplied falls. This shifts the short-run aggregate supply curve to the left.

For a summary of the factors that shift the short-run aggregate supply curve, see Table 27-2.

TABLE 12-2 Factors That Shift Aggregate Supply

The Long-Run Aggregate Supply Curve

We’ve just seen that in the short run a fall in the aggregate price level leads to a decline in the quantity of aggregate output supplied because nominal wages are sticky in the short run. But, as we mentioned earlier, contracts and informal agreements are renegotiated in the long run. So in the long run, nominal wages—like the aggregate price level—are flexible, not sticky. This fact greatly alters the long-run relationship between the aggregate price level and aggregate supply. In fact, in the long run the aggregate price level has no effect on the quantity of aggregate output supplied.

To see why, let’s conduct a thought experiment. Imagine that you could wave a magic wand—or maybe a magic bar-code scanner—and cut all prices in the economy in half at the same time. By “all prices” we mean the prices of all inputs, including nominal wages, as well as the prices of final goods and services. What would happen to aggregate output, given that the aggregate price level has been halved and all input prices, including nominal wages, have been halved?

The answer is: nothing. Consider Equation 27-2 again: each producer would receive a lower price for its product, but costs would fall by the same proportion. As a result, every unit of output profitable to produce before the change in prices would still be profitable to produce after the change in prices. So a halving of all prices in the economy has no effect on the economy’s aggregate output. In other words, changes in the aggregate price level now have no effect on the quantity of aggregate output supplied.

In reality, of course, no one can change all prices by the same proportion at the same time. But now, we’ll consider the long run, the period of time over which all prices are fully flexible. In the long run, inflation or deflation has the same effect as someone changing all prices by the same proportion. As a result, changes in the aggregate price level do not change the quantity of aggregate output supplied in the long run. That’s because changes in the aggregate price level will, in the long run, be accompanied by equal proportional changes in all input prices, including nominal wages.

The long-run aggregate supply curve shows the relationship between the aggregate price level and the quantity of aggregate output supplied that would exist if all prices, including nominal wages, were fully flexible.

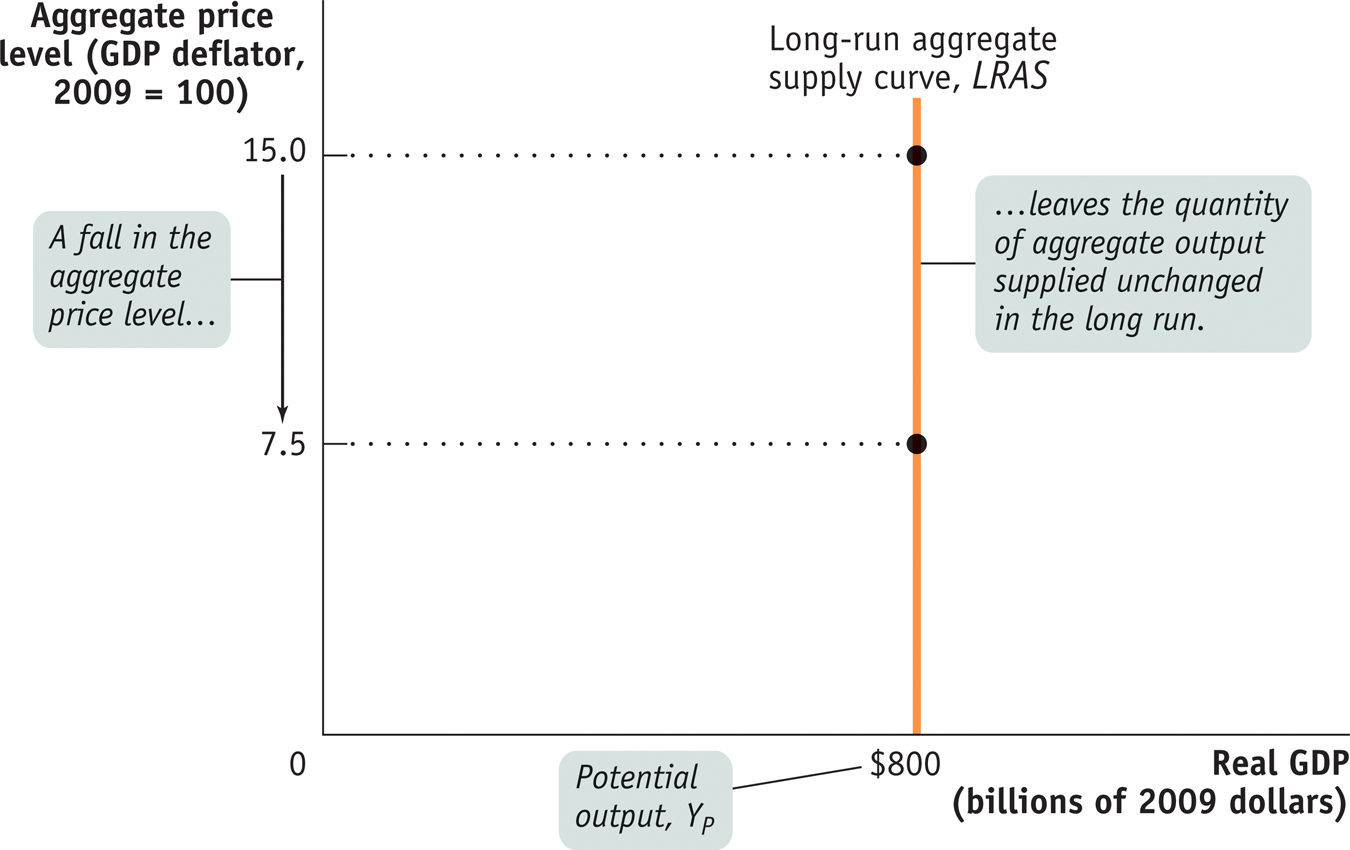

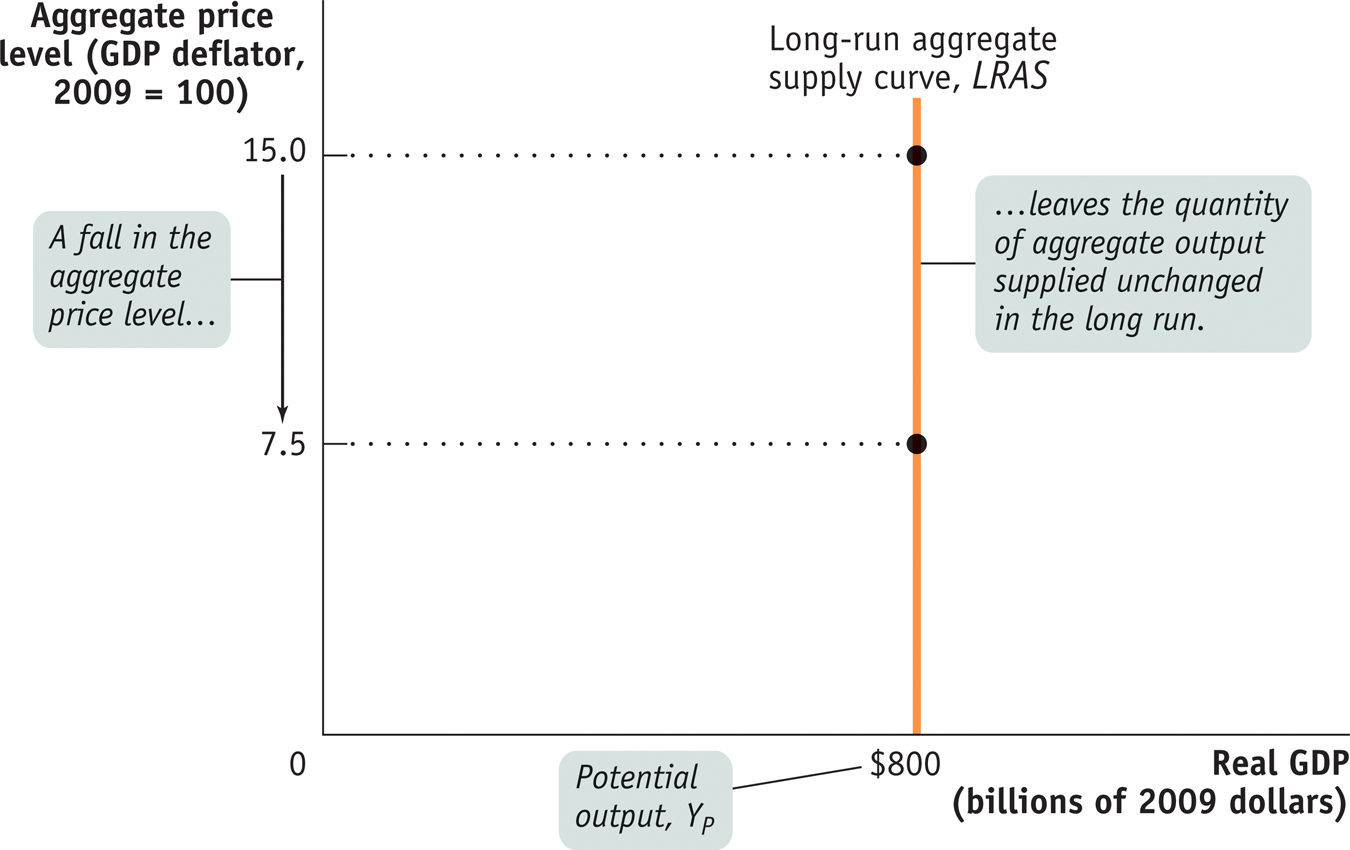

The long-run aggregate supply curve, illustrated in Figure 27-7 by the curve LRAS, shows the relationship between the aggregate price level and the quantity of aggregate output supplied that would exist if all prices, including nominal wages, were fully flexible. The long-run aggregate supply curve is vertical because changes in the aggregate price level have no effect on aggregate output in the long run. At an aggregate price level of 15.0, the quantity of aggregate output supplied is $800 billion in 2009 dollars. If the aggregate price level falls by 50% to 7.5, the quantity of aggregate output supplied is unchanged in the long run at $800 billion in 2009 dollars.

The Long-Run Aggregate Supply Curve The long-run aggregate supply curve shows the quantity of aggregate output supplied when all prices, including nominal wages, are flexible. It is vertical at potential output, YP, because in the long run a change in the aggregate price level has no effect on the quantity of aggregate output supplied.

Potential output is the level of real GDP the economy would produce if all prices, including nominal wages, were fully flexible.

It’s important to understand not only that the LRAS curve is vertical but also that its position along the horizontal axis represents a significant measure. The horizontal intercept in Figure 27-7, where LRAS touches the horizontal axis ($800 billion in 2009 dollars), is the economy’s potential output, YP: the level of real GDP the economy would produce if all prices, including nominal wages, were fully flexible.

In reality, the actual level of real GDP is almost always either above or below potential output. We’ll see why later in this chapter, when we discuss the AD–AS model. Still, an economy’s potential output is an important number because it defines the trend around which actual aggregate output fluctuates from year to year.

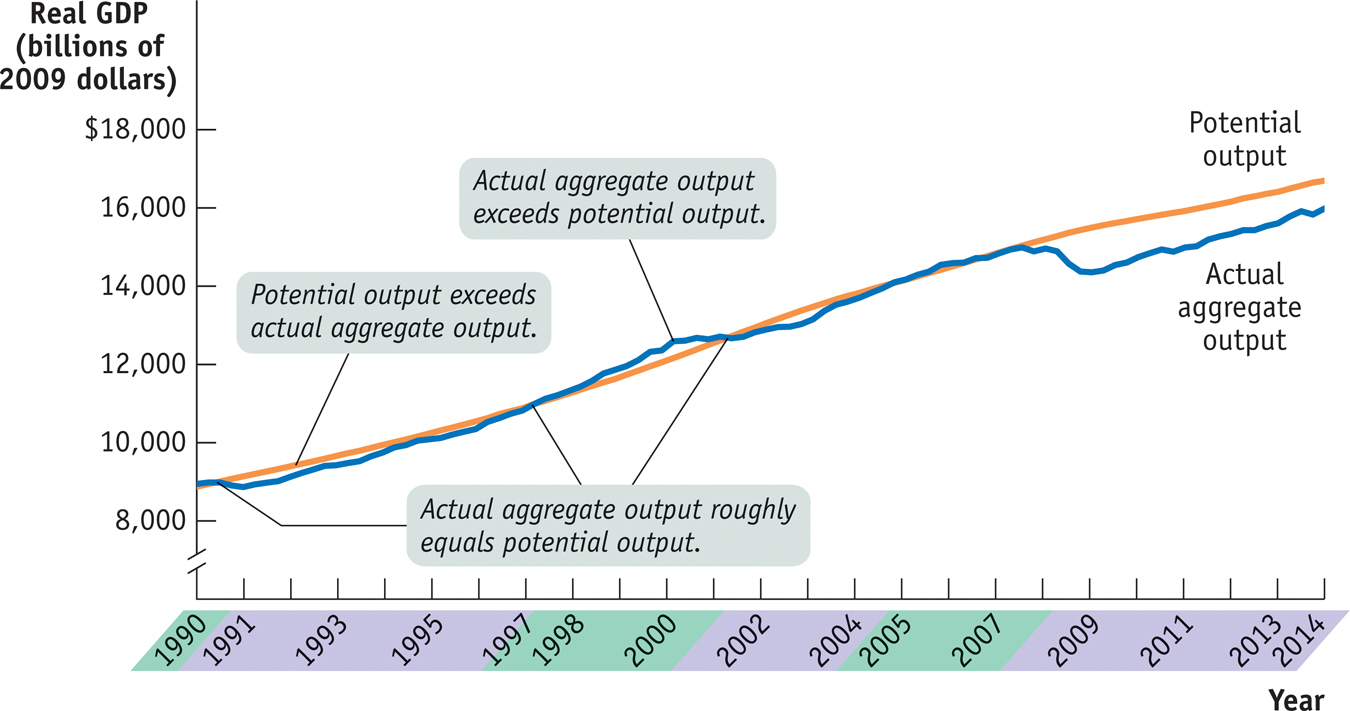

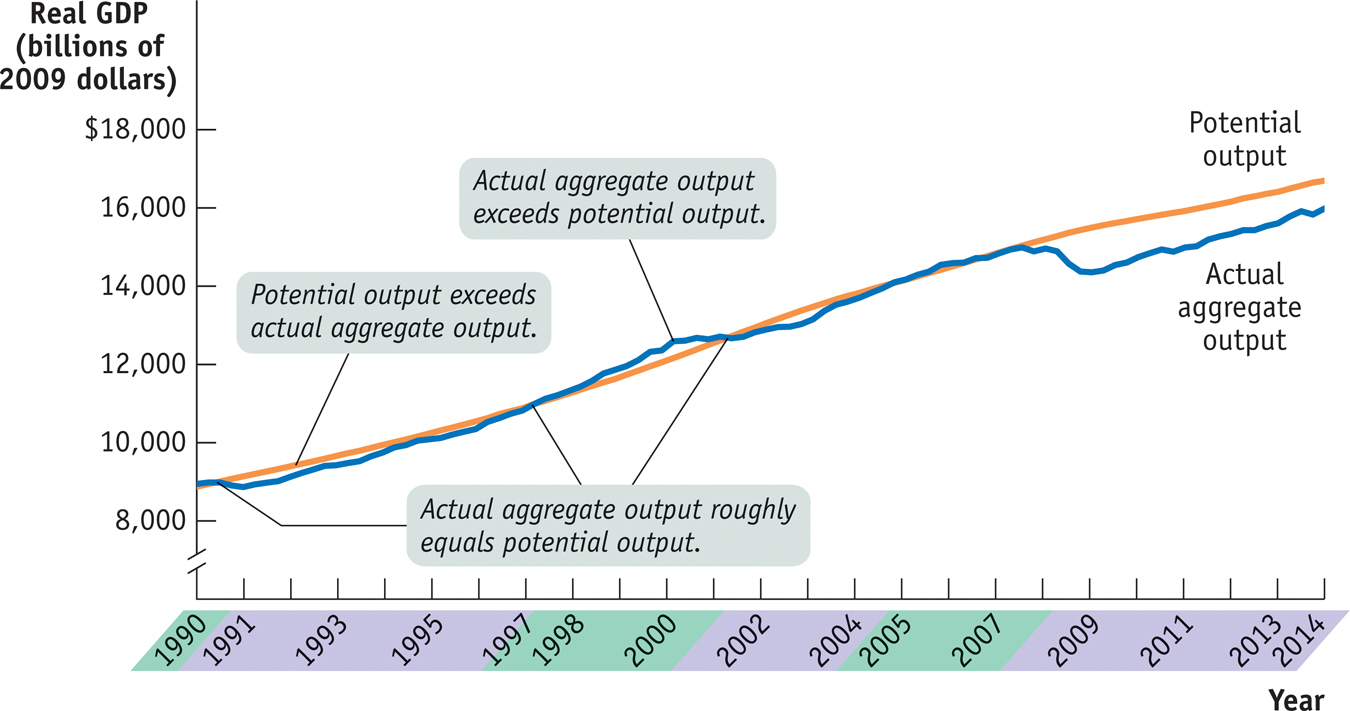

In the United States, the Congressional Budget Office, or CBO, estimates annual potential output for the purpose of federal budget analysis. In Figure 27-8, the CBO’s estimates of U.S. potential output from 1990 to 2014 are represented by the orange line and the actual values of U.S. real GDP over the same period are represented by the blue line. Years shaded purple on the horizontal axis correspond to periods in which actual aggregate output fell short of potential output, years shaded green to periods in which actual aggregate output exceeded potential output.

Actual and Potential Output from 1990 to 2014 This figure shows the performance of actual and potential output in the United States from 1990 to 2014. The orange line shows estimates of U.S. potential output, produced by the Congressional Budget Office, and the blue line shows actual aggregate output. The purple-shaded years are periods in which actual aggregate output fell below potential output, and the green-shaded years are periods in which actual aggregate output exceeded potential output. As shown, significant shortfalls occurred in the recessions of the early 1990s and after 2000. Actual aggregate output was significantly above potential output in the boom of the late 1990s, and a huge shortfall occurred after the recession of 2007–2009.Sources: Congressional Budget Office; Bureau of Economic Analysis.

As you can see, U.S. potential output has risen steadily over time—implying a series of rightward shifts of the LRAS curve. What has caused these rightward shifts? The answer lies in the factors related to long-run growth that we discussed in Chapter 24, such as increases in physical capital and human capital as well as technological progress. Over the long run, as the size of the labor force and the productivity of labor both rise, the level of real GDP that the economy is capable of producing also rises. Indeed, one way to think about long-run economic growth is that it is the growth in the economy’s potential output. We generally think of the long-run aggregate supply curve as shifting to the right over time as an economy experiences long-run growth.

From the Short Run to the Long Run

As you can see in Figure 27-8, the economy normally produces more or less than potential output: actual aggregate output was below potential output in the early 1990s, above potential output in the late 1990s, below potential output for most of the 2000s, and significantly below potential output after the recession of 2007–2009. So the economy is normally on its short-run aggregate supply curve—but not on its long-run aggregate supply curve. So why is the long-run curve relevant? Does the economy ever move from the short run to the long run? And if so, how?

The first step to answering these questions is to understand that the economy is always in one of only two states with respect to the short-run and long-run aggregate supply curves. It can be on both curves simultaneously by being at a point where the curves cross (as in the few years in Figure 27-8 in which actual aggregate output and potential output roughly coincided). Or it can be on the short-run aggregate supply curve but not the long-run aggregate supply curve (as in the years in which actual aggregate output and potential output did not coincide). But that is not the end of the story. If the economy is on the short-run but not the long-run aggregate supply curve, the short-run aggregate supply curve will shift over time until the economy is at a point where both curves cross—a point where actual aggregate output is equal to potential output.

PITFALLS

PITFALLS: ARE WE THERE YET? WHAT THE LONG RUN REALLY MEANS

ARE WE THERE YET? WHAT THE LONG RUN REALLY MEANS

We’ve used the term long run in two different contexts. In an earlier chapter we focused on long-run economic growth: growth that takes place over decades. In this chapter we introduced the long-run aggregate supply curve, which depicts the economy’s potential output: the level of aggregate output that the economy would produce if all prices, including nominal wages, were fully flexible. It might seem that we’re using the same term, long run, for two different concepts. But we aren’t: these two concepts are really the same thing.

Because the economy always tends to return to potential output in the long run, actual aggregate output fluctuates around potential output, rarely getting too far from it. As a result, the economy’s rate of growth over long periods of time—say, decades—is very close to the rate of growth of potential output. And potential output growth is determined by the factors we analyzed in the chapter on long-run economic growth. So that means that the “long run” of long-run growth and the “long run” of the long-run aggregate supply curve coincide.

Figure 27-9 illustrates how this process works. In both panels LRAS is the long-run aggregate supply curve, SRAS1 is the initial short-run aggregate supply curve, and the aggregate price level is at P1. In panel (a) the economy starts at the initial production point, A1, which corresponds to a quantity of aggregate output supplied, Y1, that is higher than potential output, YP. Producing an aggregate output level (such as Y1) that is higher than potential output (YP) is possible only because nominal wages haven’t yet fully adjusted upward. Until this upward adjustment in nominal wages occurs, producers are earning high profits and producing a high level of output. But a level of aggregate output higher than potential output means a low level of unemployment. Because jobs are abundant and workers are scarce, nominal wages will rise over time, gradually shifting the short-run aggregate supply curve leftward. Eventually it will be in a new position, such as SRAS2. (Later in this chapter, we’ll show where the short-run aggregate supply curve ends up. As we’ll see, that depends on the aggregate demand curve as well.)

From the Short Run to the Long Run In panel (a), the initial short-run aggregate supply curve is SRAS1. At the aggregate price level, P1, the quantity of aggregate output supplied, Y1, exceeds potential output, YP. Eventually, low unemployment will cause nominal wages to rise, leading to a leftward shift of the short-run aggregate supply curve from SRAS1 to SRAS2. In panel (b), the reverse happens: at the aggregate price level, P1, the quantity of aggregate output supplied is less than potential output. High unemployment eventually leads to a fall in nominal wages over time and a rightward shift of the short-run aggregate supply curve.

In panel (b), the initial production point, A1, corresponds to an aggregate output level, Y1, that is lower than potential output, YP. Producing an aggregate output level (such as Y1) that is lower than potential output (YP) is possible only because nominal wages haven’t yet fully adjusted downward. Until this downward adjustment occurs, producers are earning low (or negative) profits and producing a low level of output. An aggregate output level lower than potential output means high unemployment. Because workers are abundant and jobs are scarce, nominal wages will fall over time, shifting the short-run aggregate supply curve gradually to the right. Eventually it will be in a new position, such as SRAS2.

We’ll see shortly that these shifts of the short-run aggregate supply curve will return the economy to potential output in the long run.

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: Sticky Wages in the Great Recession

Sticky Wages in the Great Recession

We’ve asserted that the aggregate supply curve is upward-sloping in the short run mainly because of sticky wages—in particular, because employers are reluctant to cut nominal wages (and workers are unwilling to accept wage cuts) even when labor is in excess supply. But what is the evidence for wage stickiness?

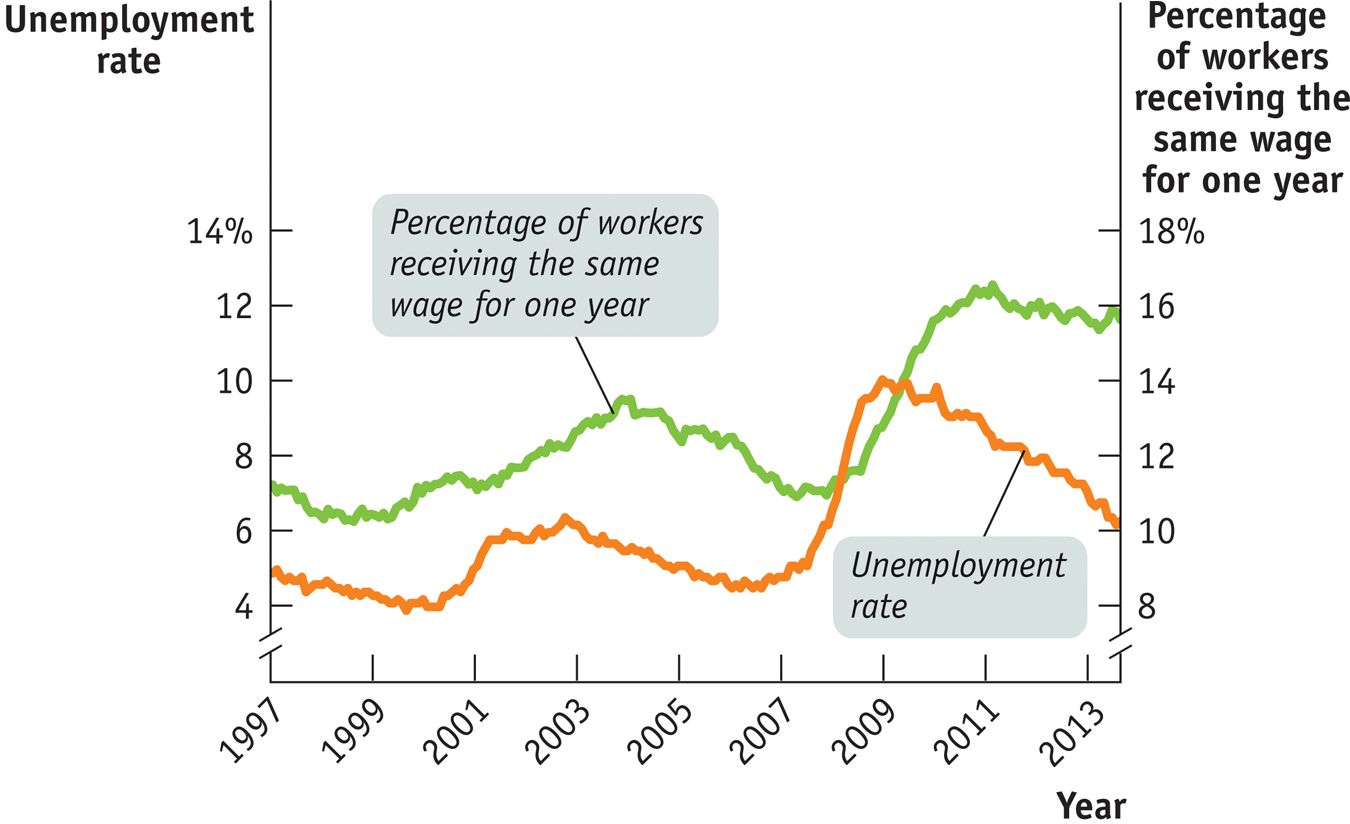

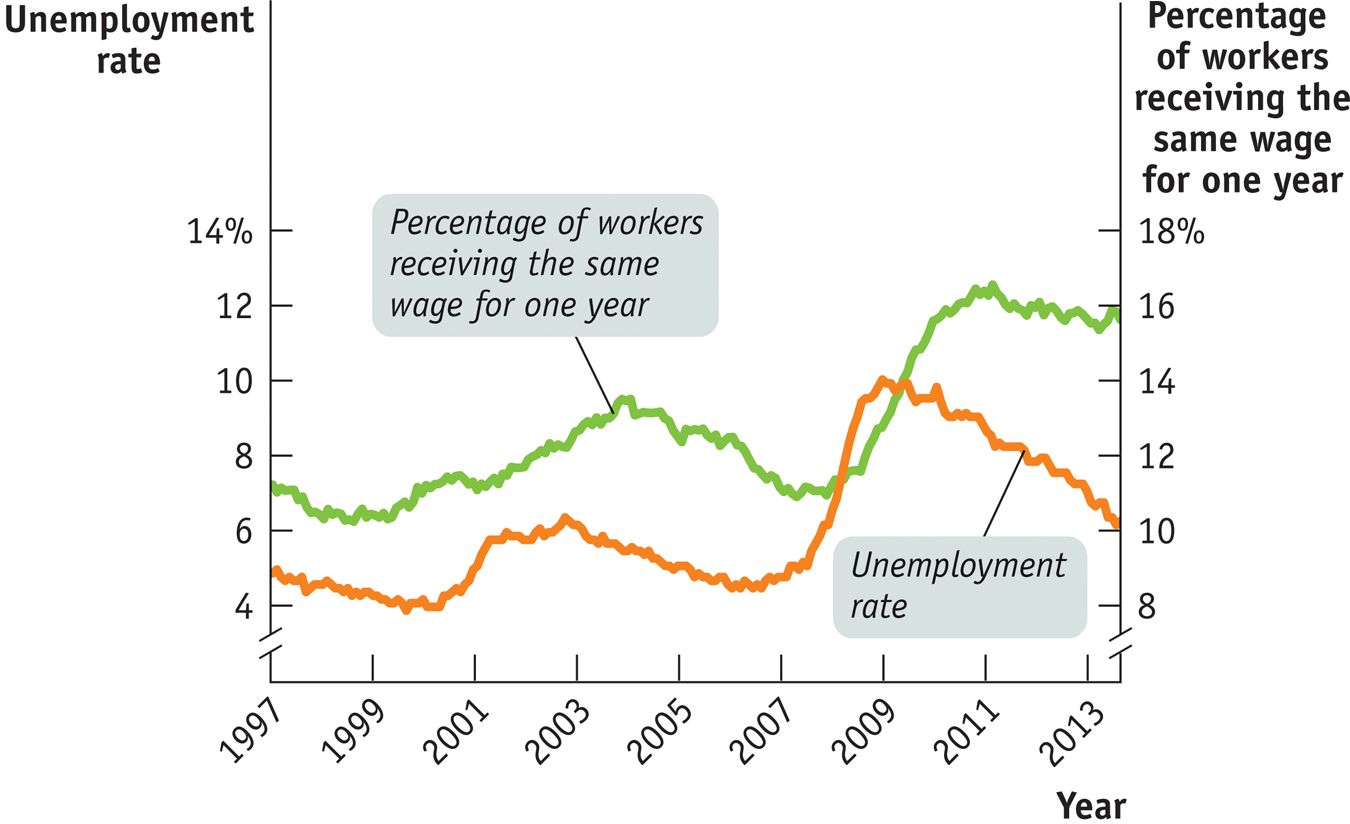

Sticky Wages in the Great RecessionSources: Bureau of Labor Statistics; Daly and Hobijn.

The answer is that we can look at what happens to wages at times when we might have expected to see many workers facing wage cuts because similar workers are unemployed and would be willing to work for less. If wages are sticky, what we would expect to find at such times is that many workers’ wages don’t change at all: there’s no reason for employers to give them a raise, but because wages are sticky, they don’t face cuts either.

And that is exactly what you find during and after the Great Recession of 2007–2009. Mary Daly and Bart Hobijn, economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, looked at data on wage changes for a sample of workers. Their findings are shown in Figure 27-10: as unemployment soared after 2007, so did the fraction of U.S. workers receiving the same wage as they did a year ago.

Similar results can be found in European nations facing high unemployment, such as Spain. The Great Recession provided strong confirmation that wages are indeed sticky.

When unemployment soared in the face of the economic slump following the 2008 financial crisis, you might have expected to see widespread wage cuts. But employers are reluctant to cut wages. So what we saw instead was a sharp rise in the number of workers whose wages were flat—neither rising nor falling.

Quick Review

The aggregate supply curve illustrates the relationship between the aggregate price level and the quantity of aggregate output supplied.

The short-run aggregate supply curve is upward sloping: a higher aggregate price level leads to higher aggregate output given that nominal wages are sticky.

Changes in commodity prices, nominal wages, and productivity shift the short-run aggregate supply curve.

In the long run, all prices are flexible, and changes in the aggregate price level have no effect on aggregate output. The long-run aggregate supply curve is vertical at potential output.

If actual aggregate output exceeds potential output, nominal wages eventually rise and the short-run aggregate supply curve shifts leftward. If potential output exceeds actual aggregate output, nominal wages eventually fall and the short-run aggregate supply curve shifts rightward.

27-2

Question

12.2

Determine the effect on short-run aggregate supply of each of the following events. Explain whether it represents a movement along the SRAS curve or a shift of the SRAS curve.

A rise in the consumer price index (CPI) leads producers to increase output.

A fall in the price of oil leads producers to increase output.

A rise in legally mandated retirement benefits paid to workers leads producers to reduce output.

Question

12.3

Suppose the economy is initially at potential output and the quantity of aggregate output supplied increases. What information would you need to determine whether this was due to a movement along the SRAS curve or a shift of the LRAS curve?

Solutions appear at back of book.