28: Fiscal Policy

!arrow! What You Will Learn in This Chapter

What fiscal policy is and why it is an important tool in managing economic fluctuations

Which policies constitute expansionary fiscal policy and which constitute contractionary fiscal policy

Why fiscal policy has a multiplier effect and how this effect is influenced by automatic stabilizers

Why governments calculate the cyclically adjusted budget balance

Why a large public debt may be a cause for concern

Why implicit liabilities of the government are also a cause for concern

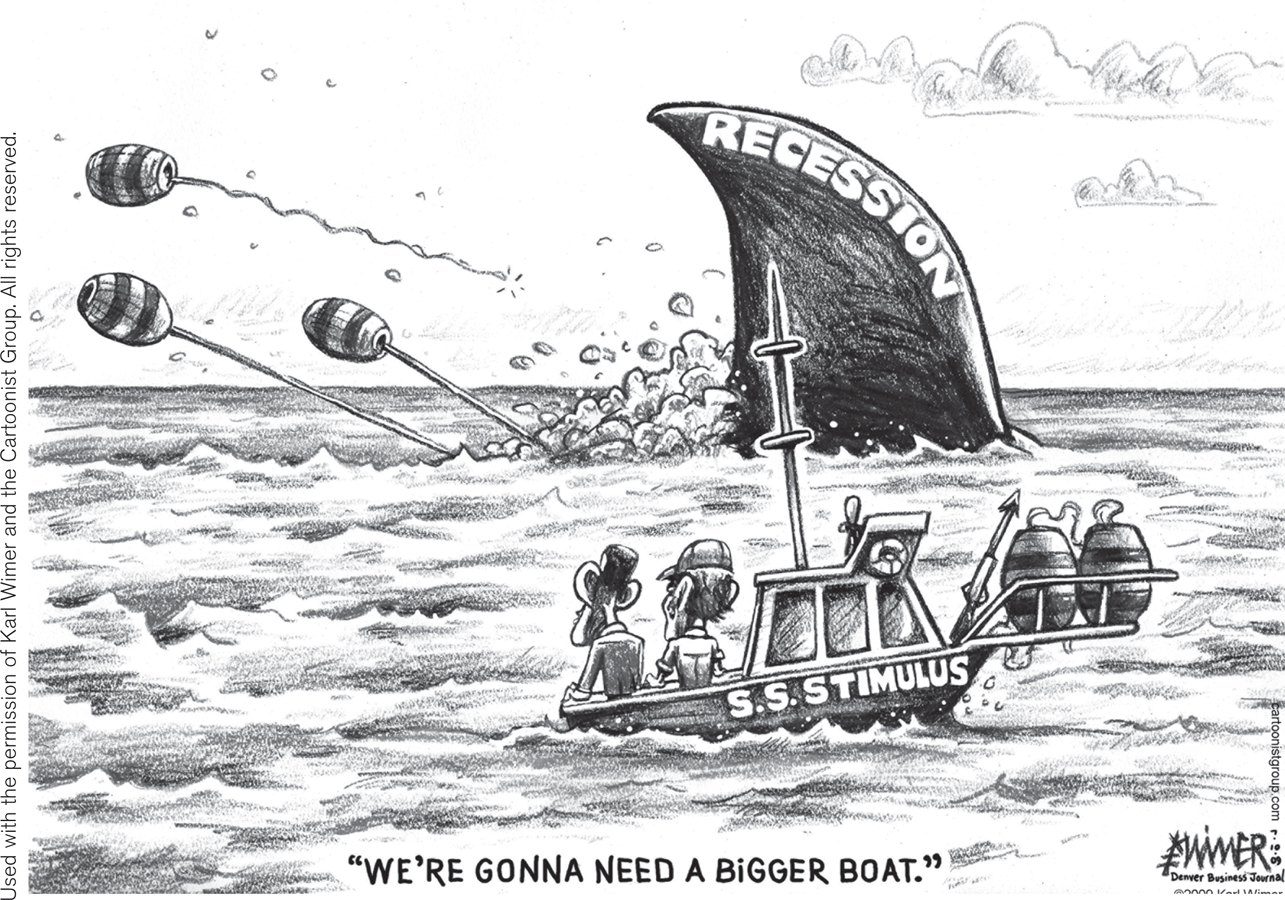

HOW BIG IS BIG ENOUGH?

On February 27, 2009, President Obama signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, a $787 billion package of spending, aid, and tax cuts intended to help the struggling U.S. economy reverse a severe recession that began in December 2007. A week earlier, as the bill neared final passage in Congress, Obama hailed the measure: “It is the right size; it is the right scope. Broadly speaking it has the right priorities to create jobs that will jumpstart our economy and transform it for the twenty-

Others weren’t so sure. Some argued that the government should be cutting spending, not increasing it, at a time when American families were suffering. “It’s time for government to tighten their belts and show the American people that we ‘get’ it,” said John Boehner, the leader of Republicans in the House of Representatives. Some economic analysts warned that the stimulus bill, as the Recovery Act was commonly called, would drive up interest rates and increase the burden of national debt.

Others had the opposite complaint—

Nor did the passage of time resolve these disputes. True, some predictions were proved false. On one side, Obama’s hope that the bill would “jumpstart” the economy fell short: although the recession officially ended in June 2009, unemployment remained high through 2011 and into 2012, by which time the stimulus had largely run its course. On the other side, the soaring interest rates predicted by stimulus opponents failed to materialize, as U.S. borrowing costs remained low by historical standards.

But the net effect of the stimulus remained controversial, with opponents arguing that it had failed to help the economy and defenders arguing that things would have been much worse without it.

Whatever the verdict—