The Interest Rate in the Short Run

As explained in Chapter 30, a fall in the interest rate leads to a rise in investment spending, I, which then leads to a rise in both real GDP and consumer spending, C. The rise in real GDP doesn’t lead only to a rise in consumer spending, however. It also leads to a rise in savings: at each stage of the multiplier process, part of the increase in disposable income is saved. How much do savings rise?

In Chapter 25 we introduced the savings–

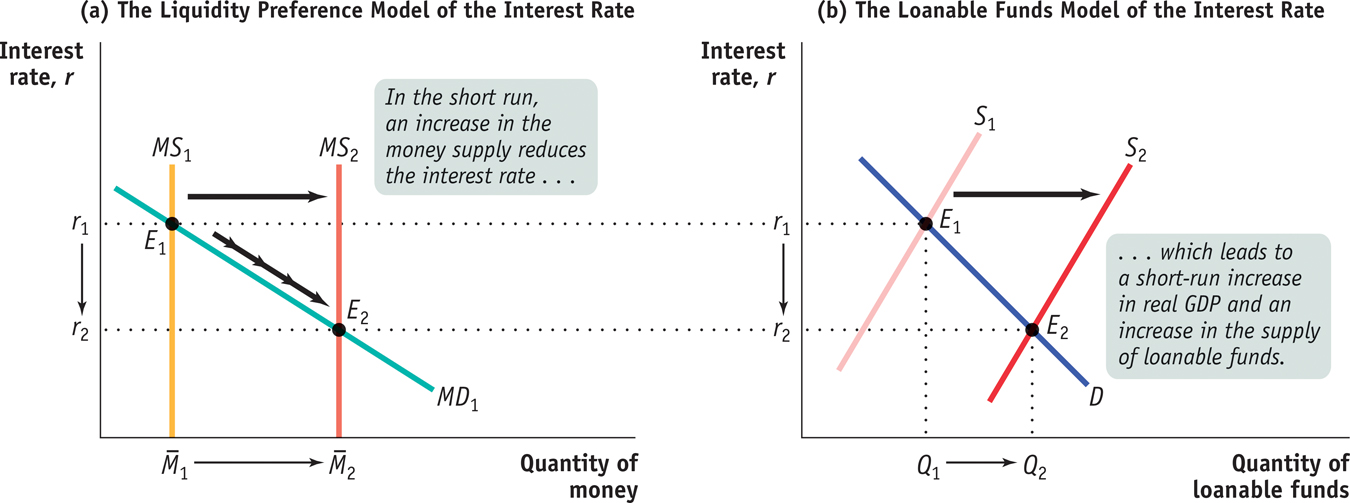

Figure 30A-1 illustrates how the two models of the interest rate are reconciled in the short run. Panel (a) shows the liquidity preference model of the interest rate where MS1 and MD1 are the initial supply and demand curves for money, and r1, the initial equilibrium interest rate, equalizes the quantity of money supplied to the quantity of money demanded in the money market. Panel (b) shows the loanable funds model of the interest rate where S1 is the initial supply curve, D is the demand curve for loanable funds, and r1, the initial equilibrium interest rate, equalizes the quantity of loanable funds supplied to the quantity of loanable funds demanded in the market for loanable funds.

In Figure 30A-1 both the money market and the market for loanable funds are initially in equilibrium at E1 with the same interest rate, r1. You might think that this would only happen by accident, but in fact it will always be true. To see why, consider what happens in panel (a), the money market, when the Fed increases the money supply from  to

to  , pushing the money supply curve rightward, to MS2, reducing the equilibrium interest rate in the market to r2, and moving the economy to a short-

, pushing the money supply curve rightward, to MS2, reducing the equilibrium interest rate in the market to r2, and moving the economy to a short-

What happens in panel (b), the market for loanable funds? In the short run, the fall in the interest rate due to the increase in the money supply leads to a rise in real GDP, which generates a rise in savings through the multiplier process. This rise in savings shifts the supply curve for loanable funds rightward, from S1 to S2, moving the equilibrium in the loanable funds market from E1 to E2 and reducing the equilibrium interest rate in the loanable funds market. Since the rise in savings must exactly match the rise in investment spending, the equilibrium rate in the loanable funds market must fall to r2, the same as the new equilibrium interest rate in the money market.

to

to  , pushes the equilibrium interest rate down, from r1 to r2. Panel (b) shows the loanable funds model of the interest rate. The fall in the interest rate in the money market leads, through the multiplier effect, to an increase in real GDP and savings; to a rightward shift of the supply curve of loanable funds, from S1 to S2; and to a fall in the interest rate, from r1 to r2. As a result, the new equilibrium interest rate in the loanable funds market matches the new equilibrium interest rate in the money market at r2.

, pushes the equilibrium interest rate down, from r1 to r2. Panel (b) shows the loanable funds model of the interest rate. The fall in the interest rate in the money market leads, through the multiplier effect, to an increase in real GDP and savings; to a rightward shift of the supply curve of loanable funds, from S1 to S2; and to a fall in the interest rate, from r1 to r2. As a result, the new equilibrium interest rate in the loanable funds market matches the new equilibrium interest rate in the money market at r2.In the short run, then, the supply and demand for money determine the interest rate, and the loanable funds market follows the lead of the money market until the equilibrium interest rate in the loanable funds market is the same as the equilibrium interest rate in the money market.

Notice our use of the phrase “in the short run.” Changes in aggregate demand affect aggregate output only in the short run. In the long run, aggregate output is equal to potential output. So our story about how a fall in the interest rate leads to a rise in aggregate output, which leads to a rise in savings, applies only to the short run.

In the long run, as we’ll see next, the determination of the interest rate is quite different, because the roles of the two markets are reversed. In the long run, the loanable funds market determines the equilibrium interest rate, and it is the market for money that follows the lead of the loanable funds market.