The Interest Rate in the Long Run

In the short run an increase in the money supply leads to a fall in the interest rate, and a decrease in the money supply leads to a rise in the interest rate. In the long run, however, changes in the money supply don’t affect the interest rate.

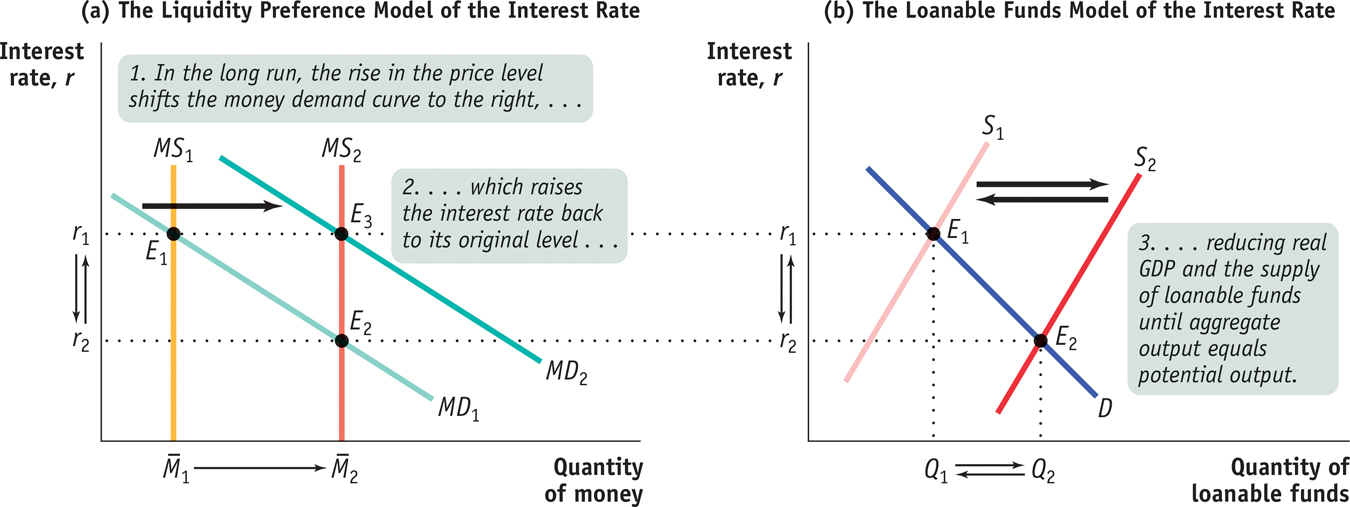

Figure 30A-2 shows why. As in Figure 30A-1, panel (a) shows the liquidity preference model of the interest rate and panel (b) shows the supply and demand for loanable funds. We assume that in both panels the economy is initially at E1, in long- . The demand curve for loanable funds is D, and the initial supply curve for loanable funds is S1. The initial equilibrium interest rate in both markets is r1.

. The demand curve for loanable funds is D, and the initial supply curve for loanable funds is S1. The initial equilibrium interest rate in both markets is r1.

to

to  ; panel (b) shows the corresponding long-

; panel (b) shows the corresponding long-Now suppose the money supply rises from  to

to  . As in Figure 30A-1, this initially reduces the interest rate to r2. According to the neutrality of money, in the long run the aggregate price level rises by the same proportion as the increase in the money supply. And we also know that a rise in the aggregate price level increases money demand by the same proportion. So in the long run the money demand curve shifts out to MD2 as money demand responds to higher prices, and moving the equilibrium interest rate rises back to its original level, r1.

. As in Figure 30A-1, this initially reduces the interest rate to r2. According to the neutrality of money, in the long run the aggregate price level rises by the same proportion as the increase in the money supply. And we also know that a rise in the aggregate price level increases money demand by the same proportion. So in the long run the money demand curve shifts out to MD2 as money demand responds to higher prices, and moving the equilibrium interest rate rises back to its original level, r1.

Panel (b) of Figure 30A-2 shows what happens in the market for loanable funds. As before, an increase in the money supply leads to a short-run rise in real GDP, and this shifts the supply of loanable funds rightward from S1 to S2. In the long run, however, real GDP falls back to its original level as wages and other nominal prices rise. As a result, the supply of loanable funds, S, which initially shifted from S1 to S2, shifts back to S1.

In the long run, then, changes in the money supply do not affect the interest rate. So what determines the interest rate in the long run, r1, in Figure 30A-2? The answer is the supply and demand for loanable funds. More specifically, in the long run the equilibrium interest rate matches the supply and demand for loanable funds that arise at potential output.