The Great Depression and the Keynesian Revolution

The Great Depression demonstrated, once and for all, that economists cannot safely ignore the short run. Not only was the economic pain severe; it threatened to destabilize societies and political systems. In particular, the economic plunge helped Adolf Hitler rise to power in Germany, setting the stage for World War II.

The whole world wanted to know how this economic disaster could be happening and what should be done about it. But because there was no widely accepted theory of the business cycle, economists gave conflicting and often harmful advice. Some believed that only a huge change in the economic system—

Some economists, however, argued that slumps were destructive and should be cured. Moreover, they could be cured without compromising the market economy. The most compelling advocate for this view, the British economist John Maynard Keynes, compared the problems of the U.S. and British economies in 1930 to those of a car with a defective starter. Getting the economy running, he argued, would require only a modest repair, not a complete overhaul.

Nice metaphor. But what did he mean, specifically?

Keynes’s Theory

In 1936 Keynes presented his analysis of the Great Depression—

As Samuelson’s description indicates, Keynes’s book offers a vast stew of ideas. Keynesian economics is principally based on two innovations. First, Keynes emphasized the importance of short-

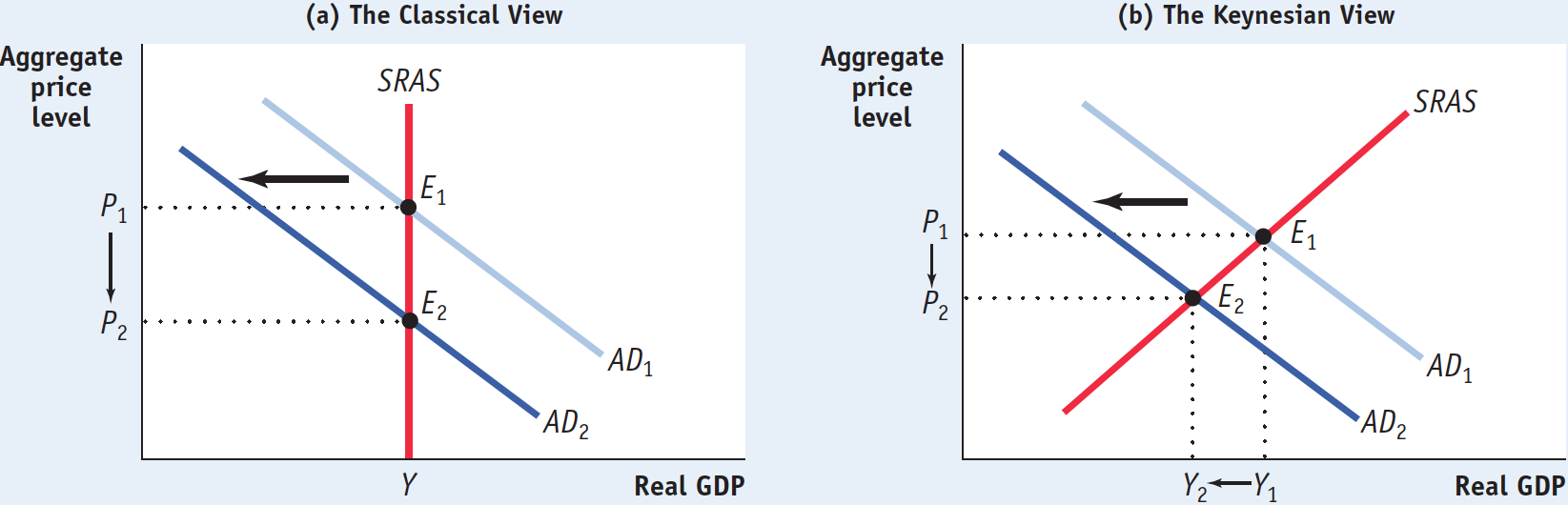

Figure 33-2 illustrates the difference between Keynesian and classical macroeconomics. Both panels of the figure show the short-

Panel (a) shows the classical view: in it, the short-

As we’ve already explained, many classical macroeconomists would have agreed that panel (b) portrayed an accurate story in the short run—

Keynes’s second innovation concerned the question of what factors shifted the aggregate demand curve and caused business cycles. Classical economists attributed shifts in the demand curve almost exclusively to changes in the money supply. Keynes, by contrast, argued that other factors, especially changes in “animal spirits”—these days usually referred to with the bland term business confidence—are mainly responsible for business cycles. Before Keynes, economists argued that as long as the money supply stayed constant, changes in factors like business confidence would have no effect on either the aggregate price level or aggregate output. Keynes offered a very different picture in which, for example, pessimism about future profits can lead to a fall in investment spending, and this can cause a recession.

Keynesian economics rests on two main tenets: changes in aggregate demand affect aggregate output, employment, and prices; and changes in business confidence cause the business cycle.

Keynesian economics, a view of the business cycle informed by these innovations, has penetrated deeply into the public consciousness, to the extent that many people who have never heard of Keynes, or have heard of him but think they disagree with his theory, use Keynesian ideas all the time. For example, suppose that a business commentator says something like this: “Businesses are holding back on investment spending because they’re worried about low consumer demand, and that’s why recovery has stalled.” Whether the commentator knows it or not, that statement is pure Keynesian economics.

FOR INQUIRING MINDS: The Politics of Keynes

Some political commentators use the term Keynesian economics as a synonym for left-

As we explained earlier, Keynesian ideas have actually been accepted among economists and policy makers across a broad range of the political spectrum. In 2004 the American president, George W. Bush, was a conservative, as was his top economist, N. Gregory Mankiw. But Mankiw is also a well-

What is true is that the rise of Keynesian economics in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s accompanied a general enlargement of the role of government in the economy, and those who favored a larger role for government tended to be enthusiastic Keynesians. Conversely, a swing of the pendulum back toward free-

Recent history shows that it is quite easy to find respected economists and policy makers who have conservative political preferences and who simultaneously respect Keynes’s fundamental contributions to macroeconomics. And as we will learn shortly, it is equally possible to find those of a liberal bent who question some of Keynes’s ideas.

Keynes himself more or less predicted that someday people would make use of his ideas without knowing that they were “Keynesians.” As he famously wrote in The General Theory, “Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.”

Policy to Fight Recessions

Macroeconomic policy activism is the use of monetary and fiscal policy to smooth out the business cycle.

The greatest consequence of Keynes’s work was that it legitimized macroeconomic policy activism—the use of monetary and fiscal policy to smooth out the business cycle.

It’s true that some economists had called for macroeconomic activism before Keynes, in particular advocating monetary expansion to fight economic downturns. And some economists had even argued, as Keynes did, that temporary budget deficits were a good thing in times of recession. But macroeconomic policy activism at the time was considered deeply controversial and those who advocated it were fiercely attacked.

As a result, when some governments during the 1930s followed policies that we would now call Keynesian, they were carried out in a half-

Over time, however, Keynesian ideas spread, and they were widely accepted among economists after World War II. There were, however, a series of challenges to those ideas, which led to a considerable shift in views even among those economists who continued to believe that Keynes was broadly right about the causes of recessions. In the upcoming section, we’ll learn about those challenges and the schools, new classical economics and new Keynesian economics, that emerged.

ECONOMICS in Action: The End of the Great Depression

The End of the Great Depression

It would make a good story if Keynes’s ideas had led to a change in economic policy that brought the Great Depression to an end. Unfortunately, that’s not what happened. Yet, the way the Depression finally ended helped convince the economics profession that Keynes was basically right.

What economists learned from Keynes’s work was that economic recovery requires aggressive fiscal expansion—

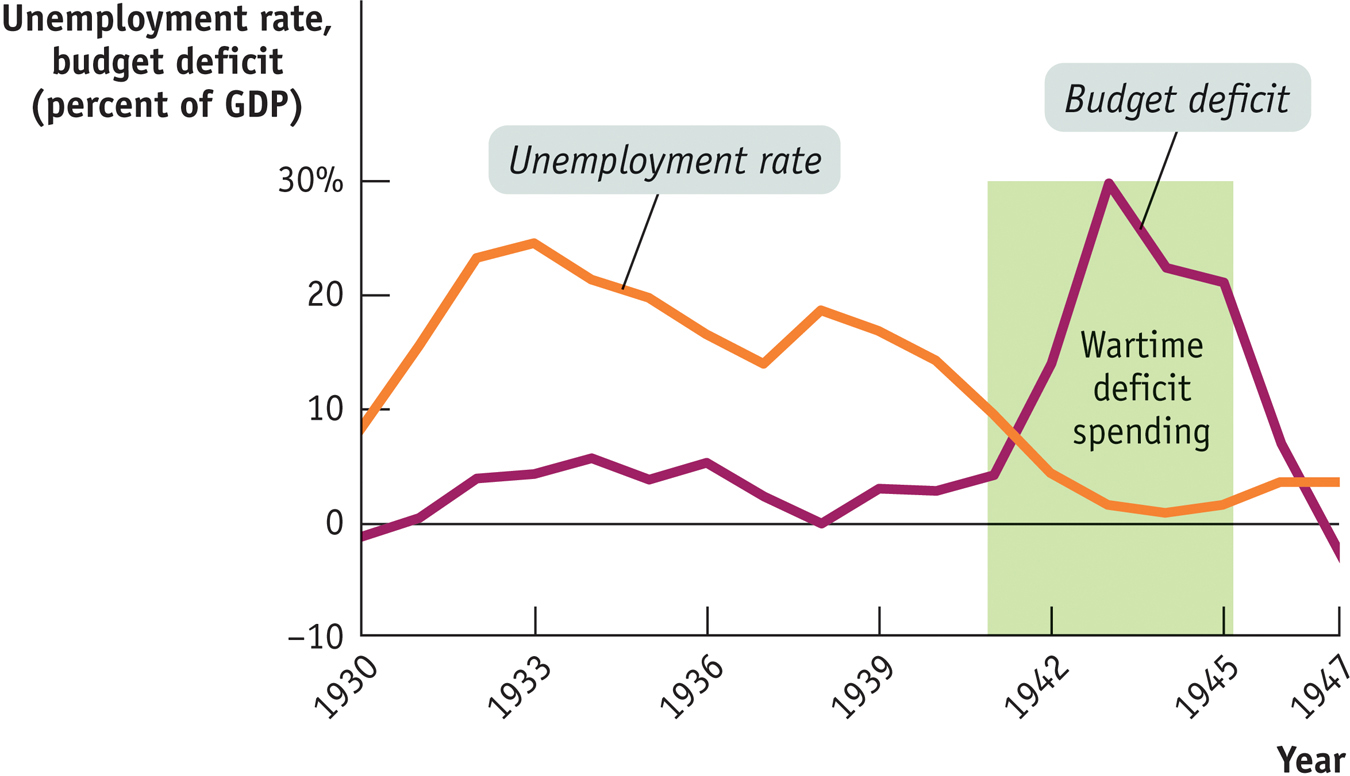

Figure 33-3 shows the U.S. unemployment rate and the federal budget deficit as a share of GDP from 1930 to 1947. As you can see, deficit spending during the 1930s was on a modest scale. In 1940, as the risk of war grew larger, the United States began a large military buildup, building tanks, planes, military bases and the like, moving the budget deep into deficit. After the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the country began deficit spending on an enormous scale: in fiscal 1943, which began in July 1942, the deficit was 30% of GDP. Today that would be equivalent to a deficit of $5.1 trillion.

What was clear to economists and policy makers was that with this enormous surge in government spending the economy, mired in the Great Depression for well over a decade, finally recovered in a sustainable way. World War II wasn’t intended as a Keynesian fiscal policy. And it is hard to believe that any event, short of a world war, would have compelled the U.S. government to spend so much money. Yet unintentional as it was, World War II spending demonstrated that expansionary fiscal policy can lift the economy out of a deep slump.

Quick Review

The key innovations of Keynesian economics are an emphasis on the short run, in which the SRAS curve slopes upward rather than being vertical, and the belief that changes in business confidence shift the AD curve and thereby generate business cycles.

Keynesian economics legitimized macroeconomic policy activism.

Keynesian ideas are widely used even by people who haven’t heard of Keynes or think they disagree with him.

33-2

Question 18.2

In a press release from early 2012, the National Federation of Independent Business, which calculates the Small Business Optimism Index, stated “The Small Business Optimism Index rose just 0.1 points in January…. Historically, optimism remains at recession levels. While small business owners appeared less pessimistic about the outlook for business conditions and real sales growth, that optimism did not materialize in hiring or increased inventories plans.” Would this statement seem familiar to a Keynesian economist? Which conclusion would a Keynesian economist draw for the need for public policy?

Solution appears at back of book.