Challenges to Keynesian Economics

Keynes’s ideas fundamentally changed the way economists think about business cycles. They did not, however, go unquestioned. In the wake of the success of government expenditures in ending the Great Depression, Keynesian economics faced a new series of challenges. As a result, by the 1980s the consensus of macroeconomists retreated somewhat from the strong version of Keynesianism that prevailed in the 1950s. In particular, many economists began to suggest limits to the effectiveness of macroeconomic policy activism.

The Revival of Monetary Policy

Many macroeconomists agree with Keynes’s view that during a depression monetary policy would be relatively ineffective. We met this phenomenon in Chapter 31 in what we called the liquidity trap, a situation in which monetary policy is ineffective because the interest rate is down against the zero bound. Remember that at the zero bound, interest rates cannot be pushed down any further to revive the economy, so expansionary monetary policy has no effect. In the 1930s, when Keynes wrote, interest rates were, in fact, very close to 0%.

When the era of near-

A key milestone in this reassessment was the 1963 publication of A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–

The revival of interest in monetary policy was significant because it suggested that the burden of managing the economy could be shifted away from fiscal policy—

Monetary policy, in contrast, does not involve such political choices: when the central bank cuts interest rates to fight a recession, it cuts everyone’s interest rate at the same time. So a shift from relying on fiscal policy to relying on monetary policy makes macroeconomics a more technical, less political undertaking. In fact, as we learned in Chapter 29, monetary policy in most major economies is set by an independent central bank that is insulated from the political process.

Monetarism

Monetarism asserts that GDP will grow steadily if the money supply grows steadily.

After the publication of A Monetary History, Milton Friedman led a movement that sought to eliminate all forms of macroeconomic policy activism—

It’s important to realize that monetarism retained many Keynesian ideas. Like Keynes, Friedman asserted that the short run is important and that short-

Discretionary monetary policy is the use of changes in the interest rate or the money supply to stabilize the economy.

Monetarists argued, however, that in most cases activist macroeconomic policy to smooth out the business cycle actually makes things worse. In Chapter 28 we described how lags can cause problems for discretionary fiscal policy. For example, a government that tries to respond to recessions by increasing spending sometimes finds that by the time it realizes that a recession is underway, takes action, and gets results, the recession is over, and the spending increase feeds a boom instead of fighting a slump. According to monetarists, discretionary monetary policy, changes in the interest rate or the money supply by the central bank in order to stabilize the economy, faces similar problems and can easily make the economy less stable.

Friedman also argued that if the central bank followed his advice, adopting a non-

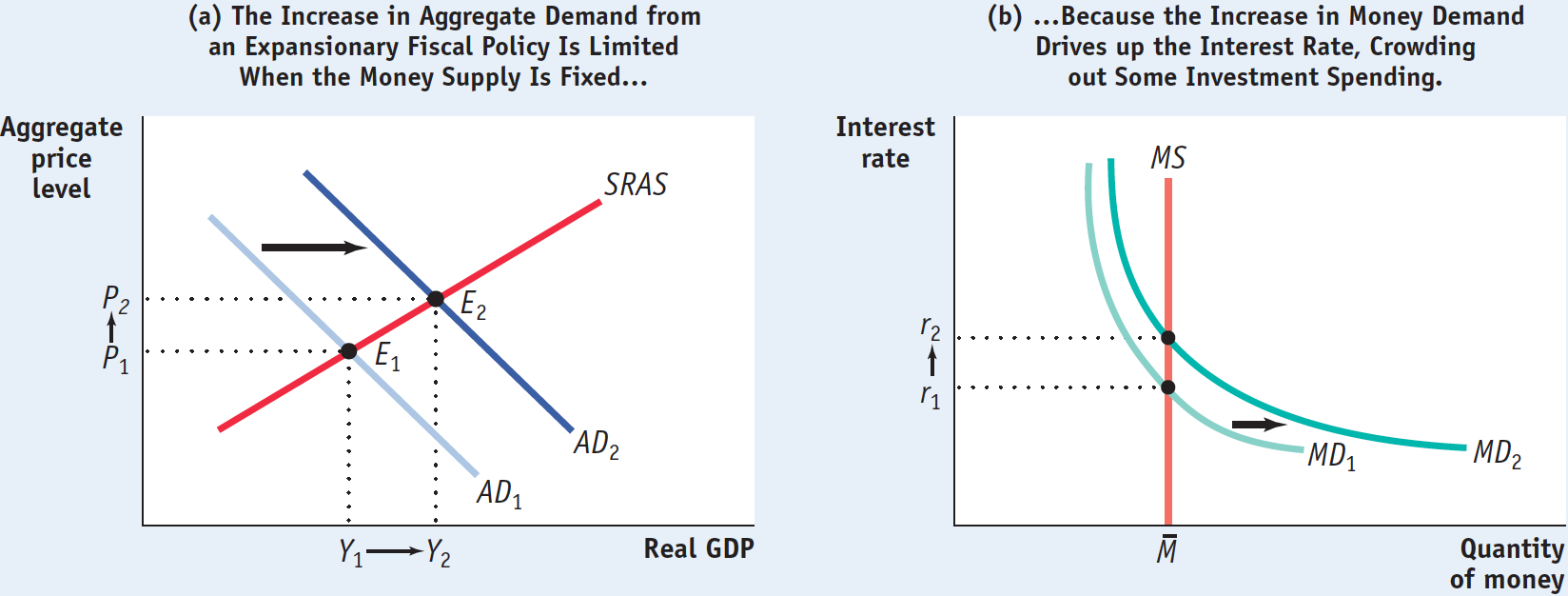

Figure 33-4 illustrates this argument. Panel (a) shows aggregate output and the aggregate price level. AD1 is the initial aggregate demand curve and SRAS is the short-

Now suppose the government increases purchases of goods and services. We know that this will shift the AD curve rightward, as illustrated by the shift from AD1 to AD2, and that aggregate output will rise, from Y1 to Y2, and the aggregate price level will rise, from P1 to P2. Both the rise in aggregate output and the rise in the aggregate price level will, however, increase the demand for money, shifting the money demand curve rightward from MD1 to MD2. This drives up the equilibrium interest rate to r2. Friedman’s point was that this rise in the interest rate reduces investment spending, partially offsetting the initial rise in government spending. As a result, the rightward shift of the AD curve is smaller than the multiplier analysis in Chapter 28 indicated. And Friedman argued that with a constant rate of increase in the money supply, the multiplier is so small that there’s not much point in using fiscal policy, even in a depressed economy.

A monetary policy rule is a formula that determines the central bank’s actions.

As we’ve already noted, Friedman didn’t favor activist monetary policy either, arguing that the problems of time lags that limit the ability of discretionary fiscal policy to stabilize the economy also apply to discretionary monetary policy. Friedman’s solution was to make monetary policy nondiscretionary, to put it on “autopilot.” The central bank, he argued, should follow a monetary policy rule, a formula that determines its actions and leaves it relatively little discretion. During the 1960s and 1970s, most monetarists favored a monetary policy rule of slow, steady growth in the money supply.

The velocity of money is the ratio of nominal GDP to the money supply.

Underlying this view was the concept of the velocity of money, the ratio of nominal GDP to the money supply. Velocity is a measure of the number of times the average dollar bill in the economy turns over per year between buyers and sellers (e.g., I tip the Starbucks barista a dollar, she uses it to buy lunch, and so on). This concept gives rise to the velocity equation, which relates nominal GDP to the money supply:

Monetarists believed, with considerable historical justification, that the velocity of money, V, was stable in the short run and changes only slowly in the long run. As a result, they claimed, steady growth in M, the money supply, by the central bank would ensure steady growth in spending, and therefore in GDP.

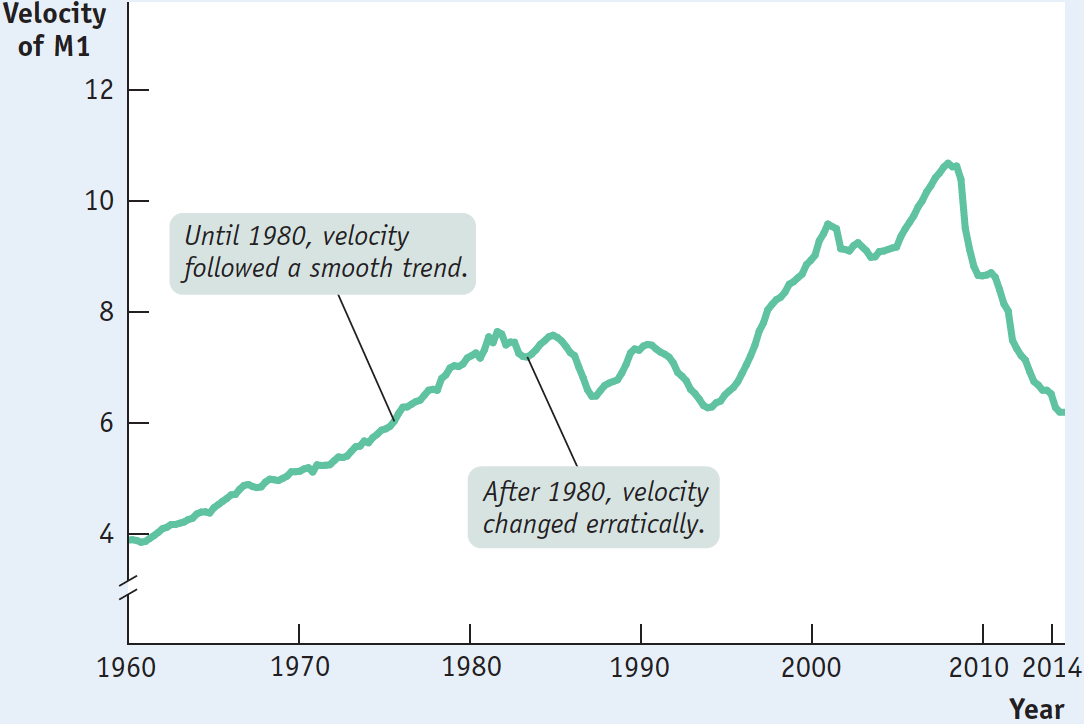

Monetarism strongly influenced U.S. monetary policy in the late 1970s and early 1980s as the Fed tried to keep the rate of growth in the money supply constant. It quickly became clear, however, that this didn’t ensure steady growth in the economy: the velocity of money wasn’t stable enough for such a simple policy rule to work. Figure 33-5 shows how events eventually undermined the monetarists’ view. The figure shows the velocity of money, as measured by the ratio of nominal GDP to M1, from 1960 through mid-

Consequently, traditional monetarists—

Limits to Macroeconomic Policy: Inflation and the Natural Rate of Unemployment

The problem of time lags in the implementation of activist macroeconomic policy was not the only criticism leveled at Keynesian economics. Another serious concern arose over its effect on inflation. During the 1940s and 1950s, many Keynesian economists believed that expansionary fiscal policy could be used to achieve full employment on a permanent basis. By the 1960s, however, many economists realized that persistently expansionary policies could cause problems with inflation. Yet they still believed that governments could choose to keep unemployment low if they were willing to accept higher inflation.

According to the natural rate hypothesis, because inflation is eventually embedded into expectations, to avoid accelerating inflation over time the unemployment rate must be high enough that the actual inflation rate equals the expected inflation rate.

In 1968, however, Milton Friedman and Edmund Phelps of Columbia University, working independently, argued that there isn’t actually a long-

And the natural rate hypothesis was, in fact, accepted by most economists after the 1970s. The Friedman–

The Political Business Cycle

One final challenge to Keynesian economics focused not on the validity of the economic analysis but on its political consequences. A number of economists and political scientists pointed out that activist macroeconomic policy lends itself to political manipulation.

A political business cycle results when politicians use macroeconomic policy to serve political ends.

Statistical evidence suggests that election results tend to be determined largely by the state of the economy in the months just before the election. In the United States, if the economy is growing rapidly and the unemployment rate is falling in the six months or so before Election Day, the incumbent party tends to be reelected even if the economy performed poorly in the preceding three years. This creates an obvious temptation to abuse activist macroeconomic policy: pump up the economy in an election year, and pay the price in higher inflation and/or higher unemployment later. The consequence will be unnecessary instability in the economy, a political business cycle caused by the use of macroeconomic policy to serve political ends.

An often-

As we’ve learned, one way to avoid a political business cycle is to place monetary policy in the hands of an independent central bank, insulated from political pressure. The political business cycle is also a reason to limit the use of discretionary fiscal policy to extreme circumstances like a liquidity trap.

ECONOMICS in Action: The Fed’s Flirtation with Monetarism

The Fed’s Flirtation with Monetarism

In the late 1970s and early 1980s the Federal Reserve flirted with monetarism. For most of its prior existence, the Fed had targeted interest rates, adjusting its target based on the state of the economy. In the late 1970s, however, the Fed adopted a monetary policy rule and began announcing target ranges for several measures of the money supply. It also stopped setting targets for interest rates. Most people interpreted these changes as a strong move toward monetarism.

In 1982, however, the Fed turned its back on monetarism. Since 1982 the Fed has pursued a discretionary monetary policy, which has led to large swings in the money supply. At the end of the 1980s, the Fed returned to conducting monetary policy by setting target levels for the interest rate.

Why did the Fed flirt with monetarism, then abandon it? The turn to monetarism largely reflected the events of the 1970s, when a sharp rise in inflation broke the perceived trade-

The turn away from monetarism also reflected events: as we saw in Figure 33-5, the velocity of money, which had followed a smooth trend before 1980, became erratic after 1980. This made monetarism seem like a much less good idea.

Quick Review

Early Keynesianism downplayed the effectiveness of monetary as opposed to fiscal policy, but later macroeconomists realized that monetary policy is effective except in the case of a liquidity trap.

According to monetarism, due to time lags, both discretionary fiscal policy and discretionary monetary policy do more harm than good, and a simple monetary policy rule is the best way to stabilize the economy. Monetarists believed that the velocity of money was stable and therefore steady growth of the money supply would lead to steady growth of GDP. This doctrine was popular for a time but has fallen out of favor as its predictions failed to materialize.

The natural rate hypothesis, now very widely accepted, places sharp limits on what macroeconomic policy can achieve. It implies that policy should aim to stabilize the unemployment rate around the natural rate.

Concerns about a political business cycle suggest that the central bank should be independent and that discretionary fiscal policy should be avoided except in extreme circumstances like a liquidity trap.

33-3

Question 18.3

Consider Figure 33-5.

If the Federal Reserve had pursued a monetarist policy of a constant rate of growth in the money supply, what would have happened to output beginning in 2008 according to the velocity equation?

In fact, the Federal Reserve accelerated the rate of growth in M1 rapidly beginning in 2008, partly in order to counteract a large increase in unemployment. Would a monetarist have agreed with this policy? What limits are there, according to a monetarist point of view, to changing the unemployment rate?

Question 18.4

What are the limits of macroeconomic policy activism?

Solutions appear at back of book.