Rational Expectations, Real Business Cycles, and New Classical Macroeconomics

As we have seen, one key difference between classical economics and Keynesian economics is that classical economists believed that the short-

However, the challenges to Keynesian economics that arose in the 1950s and 1960s from monetarists and from natural rate theorists didn’t rely on classical economics ideas. The challengers accepted an upward-

New classical macroeconomics is an approach to the business cycle that returns to the classical view that shifts in the aggregate demand curve affect only the aggregate price level, not aggregate output.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the classical view that shifts in the aggregate demand curve affect only the aggregate price level, not aggregate output, was revived in an approach known as new classical macroeconomics. It evolved in two stages. First, some economists challenged traditional arguments about the slope of the short-

Rational Expectations

Rational expectations is the view that individuals and firms make decisions optimally, using all available information.

In the 1970s a concept known as rational expectations had a powerful impact on macroeconomics. Rational expectations, originally introduced by John Muth in 1961, claims that individuals and firms make decisions optimally, using all available information.

For example, workers and employers bargaining over long-

Adopting the premise of rational expectations can significantly alter beliefs about the effectiveness of activist macroeconomic policy. According to the original version of the natural rate hypothesis, a government attempt to persistently push the unemployment rate below the natural rate would work in the short run but will eventually fail because higher inflation will get built into expectations. According to rational expectations, we should remove the word eventually and replace it with immediately: if the government tries to lower unemployment today at the cost of higher inflation in the future, inflation will shoot up immediately without even a temporary fall in unemployment. So, under rational expectations, government intervention fails in the short run and the long run.

According to the rational expectations model of the economy, expected changes in monetary policy have no effect on unemployment and output and only affect the price level.

In the 1970s Robert Lucas of the University of Chicago, in a series of highly influential papers, used the logic of rational expectations to argue that monetary policy can change the level of output and unemployment only if it comes as a surprise to the public. Otherwise, attempts to lower unemployment will simply result in higher prices. According to Lucas’s rational expectations model of the economy, monetary policy isn’t useful in stabilizing the economy after all. In 1995 Lucas won the Nobel Prize in economics for this work, which remains widely admired. However, many—

According to new Keynesian economics, market imperfections can lead to price stickiness for the economy as a whole.

Why, in the view of many macroeconomists, doesn’t Lucas’s rational expectations model of macroeconomics accurately describe how the economy actually behaves? New Keynesian economics, a set of ideas that became influential in the 1990s, provides an explanation. It argues that market imperfections interact to make many prices in the economy temporarily sticky. And with sticky prices, expected inflation can’t rise quickly enough to offset activist macroeconomic policy.

For example, one new Keynesian argument points out that monopolists don’t have to be too careful about setting prices exactly “right”: if they set a price a bit too high, they’ll lose some sales but make more profit on each sale; if they set the price too low, they’ll reduce the profit per sale but sell more. As a result, even small costs to changing prices can lead to substantial price stickiness and make the economy as a whole behave in a Keynesian fashion.

Over time, new Keynesian ideas combined with actual experience have reduced the practical influence of the rational expectations concept. Nonetheless, the idea of rational expectations served as a useful caution for macroeconomists who had become excessively optimistic about their ability to manage the economy.

Real Business Cycles

Real business cycle theory claims that fluctuations in the rate of growth of total factor productivity cause the business cycle.

In Chapter 24 we introduced the concept of total factor productivity, the amount of output that can be generated with a given level of factor inputs. Total factor productivity grows over time, but that growth isn’t smooth. In the 1980s a number of economists argued that slowdowns in productivity growth, which they attributed to pauses in technological progress, are the main cause of recessions. Real business cycle theory claims that fluctuations in the rate of growth of total factor productivity cause the business cycle.

Believing that the aggregate supply curve is vertical, real business cycle theorists attribute the source of business cycles to shifts of the aggregate supply curve: a recession occurs because a slowdown in productivity growth shifts the aggregate supply curve leftward, and a recovery occurs because a pickup in productivity growth shifts the aggregate supply curve rightward. In the early days of real business cycle theory, the theory’s proponents denied that changes in aggregate demand—

FOR INQUIRING MINDS: Supply-Side Economics

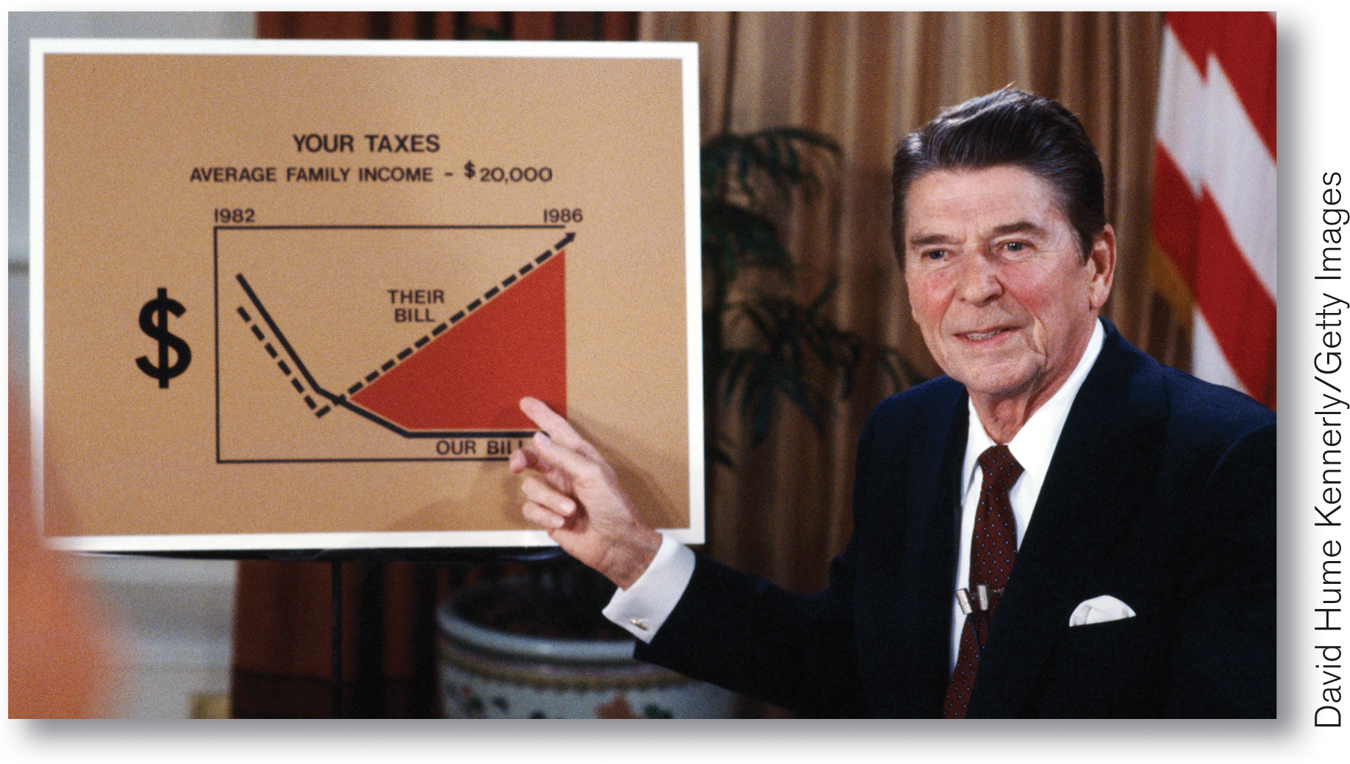

During the 1970s a group of economic writers began propounding a view of economic policy that came to be known as supply-

Some supply-

In the 1970s supply-

Because supply-

The main reason for this dismissal is lack of supporting evidence. Almost all economists agree that tax cuts increase incentives to work and invest. But attempts to estimate these incentive effects indicate that at current U.S. tax levels, the positive incentive effects aren’t nearly strong enough to support the strong claims made by supply-

This theory was strongly influential, reflected by the fact that two of the founders of real business cycle theory, Finn Kydland of Carnegie Mellon University and Edward Prescott of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, won the 2004 Nobel Prize in economics. The current status of real business cycle theory, however, is somewhat similar to that of rational expectations. The theory is widely recognized as having made valuable contributions to our understanding of the economy, and it serves as a useful caution against too much emphasis on aggregate demand.

But many of the real business cycle theorists themselves now acknowledge that the actual economic data indicate that their models need an upward-

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: The 1970s in Reverse

The 1970s in Reverse

When economists talk about the natural rate hypothesis, they usually frame it in terms of what happens if the government tries to keep unemployment low. The hypothesis says that sustained low unemployment will lead to ever-

As it turned out, the prediction wasn’t very successful. Inflation in the United States has generally been somewhat lower since the Great Recession than it was before, but the United States never entered deflation. By 2014 prices were falling in some European countries with very high unemployment, but there was no sign of accelerating deflation.

The failure of deflation to materialize didn’t come as a complete surprise, since some economists had long argued that the natural rate hypothesis breaks down at low inflation. However, that view became much more widespread after 2008 than it had been before—

In that sense the era since the Great Recession has been the 1970s in reverse, with Keynesian views gaining strength in the light of experience.

Quick Review

According to new classical macroeconomics, the short-

run aggregate supply curve is vertical after all. It contains two branches: the rational expectations model and real business cycle theory. Rational expectations claims that people take all information into account. The rational expectations model of the economy claims that only unexpected changes in monetary policy affect aggregate output and employment; expected changes only alter the price level.

New Keynesian economics argues that due to market imperfections that create price stickiness, the aggregate supply curve is upward-

sloping; therefore changes in aggregate demand affect aggregate output and employment. Real business cycle theory argues that fluctuations in the rate of productivity growth cause the business cycle.

New Keynesian ideas and events have diminished the acceptance of the rational expectations model, while real business cycle theory has been undermined by its implication that technology regresses during deep recessions. It is now generally believed that the aggregate supply curve is upward-

sloping.

33-4

Question 18.5

In late 2008, as it became clear that the United States was experiencing a recession, the Fed reduced its target for the federal funds rate to near zero, as part of a larger aggressively expansionary monetary policy stance (including what the Fed called quantitative easing). Most observers agreed that the Fed’s aggressive monetary expansion helped reduce the length and severity of the Great Recession.

What would rational expectations theorists say about this conclusion?

What would real business cycle theorists say?

Solutions appear at back of book.