Capital Flows and the Balance of Payments

In 2013 people living in the United States sold about $4.2 trillion worth of stuff to people living in other countries and bought about $4.2 trillion worth of stuff in return. What kind of stuff? All kinds. Residents of the United States (including firms operating in the United States) sold airplanes, bonds, wheat, and many other items to residents of other countries. Residents of the United States bought cars, stocks, oil, and many other items from residents of other countries.

How can we keep track of these transactions? In Chapter 22 we learned that economists keep track of the domestic economy using the national income and product accounts. Economists keep track of international transactions using a different but related set of numbers, the balance of payments accounts.

Balance of Payments Accounts

A country’s balance of payments accounts are a summary of the country’s transactions with other countries.

A country’s balance of payments accounts are a summary of the country’s transactions with other countries for a given year.

To understand the basic idea behind the balance of payments accounts, let’s consider a small-

They made $100,000 by selling artichokes.

They spent $70,000 on running the farm, including purchases of new farm machinery, and another $40,000 buying food, paying utility bills, replacing their worn-

out car, and so on. They received $500 in interest on their bank account but paid $10,000 in interest on their mortgage.

They took out a new $25,000 loan to help pay for farm improvements but didn’t use all the money immediately. So they put the extra in the bank.

How could we summarize the Costas’ transactions for the year? One way would be with a table like Table 34-1, which shows sources of cash coming in and uses of cash going out, characterized under a few broad headings. The first row of Table 34-1 shows sales and purchases of goods and services: sales of artichokes; purchases of groceries, heating oil, that new car, and so on. The second row shows interest payments: the interest the Costas received from their bank account and the interest they paid on their mortgage. The third row shows loans and deposits: cash coming in from a loan and cash deposited in the bank.

|

|

Sources of cash |

Uses of cash |

Net |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Purchases or sales of goods and services |

Artichoke sales: $100,000 |

Farm operation and living expenses: $110,000 |

−$10,000 |

|

Interest payments |

Interest received on bank account: $500 |

Interest paid on mortgage: $10,000 |

−$9,500 |

|

Loans and deposits |

Funds received from new loan: $25,000 |

Funds deposited in bank: $5,500 |

+$19,500 |

|

Total |

$125,500 |

$125,500 |

$0 |

TABLE 19-

In each row we show the net inflow of cash from that type of transaction. So the net in the first row is −$10,000, because the Costas spent $10,000 more than they earned. The net in the second row is −$9,500, the difference between the interest the Costas received on their bank account and the interest they paid on the mortgage. The net in the third row is $19,500: the Costas brought in $25,000 with their new loan but put only $5,500 of that sum in the bank.

The last row shows the sum of cash coming in from all sources and the sum of all cash used. These sums are equal, by definition: every dollar has a source, and every dollar received gets used somewhere. (What if the Costas hid money under the mattress? Then that would be counted as another “use” of cash.)

A country’s balance of payments accounts is a table which summarizes the country’s transactions with the rest of the world for a given year in a manner very similar to the way we just summarized the Costas’ financial year.

Table 34-2 shows a simplified version of the U.S. balance of payments accounts for 2013. Where the Costa family’s accounts show sources and uses of cash, a country’s balance of payments accounts show payments from foreigners—

|

|

Payments from foreigners |

Payments to foreigners |

Net |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Sales and purchases of goods and services |

$2,280 |

$2,756 |

–$476 |

|

2 |

Factor income |

780 |

580 |

199 |

|

3 |

Transfers |

118 |

242 |

–124 |

|

|

Current account (1 + 2 + 3) |

|

|

–400 |

|

4 |

Asset sales and purchases (financial account) |

1,018 |

–645 |

373 |

|

|

Financial account (4) |

|

|

373 |

|

|

Statistical discrepancy |

— |

— |

–27 |

|

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics. |

||||

TABLE 19-

Row 1 of Table 34-2 shows payments that arise from U.S. sales to foreigners and U.S. purchases from foreigners of goods and services in 2013. For example, the number in the second column of row 1, $2,280 billion, incorporates items such as the value of U.S. wheat exports and the fees foreigners pay to U.S. consulting companies in 2013. The number in the third column of row 1, $2,756 billion, incorporates items such as the value of U.S. oil imports and the fees U.S. companies pay to Indian call centers—

Row 2 shows U.S. factor income in 2013—

Row 3 shows international transfers for the U.S. in 2013—

Row 4 of the table contains payments accruing from sales and purchases of assets between American residents and foreigners in 2013. For example, in 2013 Shanghui, a Chinese food company, purchased Smithfield Foods, America’s top pork packager, for $4.7 billion. As a payment to the American owners of Smithfield Foods for the purchase of their assets, that $4.7 billion is included in the figure $1,018 billion, found in the second column of row 4. Also in 2013, some major Wall Street firms were buying European debt, both private and public. As a payment by American residents to foreigners for the purchase of foreign assets, these purchases are included in the −$645 billion figure located in the third column of row 4.

In laying out Table 34-2, we have separated rows 1, 2, and 3 into one group, to distinguish them from row 4. This reflects a fundamental difference in how these two groups of transactions affect the future. When a U.S. resident sells a good such as wheat to a foreigner, that’s the end of the transaction. But a financial asset, such as a bond, is different. Remember, a bond is a promise to pay interest and principal in the future. So when a U.S. resident sells a bond to a foreigner, that sale creates a liability: the U.S. resident will have to pay interest and repay principal in the future. The balance of payments accounts distinguish between transactions that don’t create liabilities and those that do.

A country’s balance of payments on current account, or current account, is its balance of payments on goods and services plus net international transfer payments and factor income.

Transactions that don’t create liabilities are considered part of the balance of payments on current account, often referred to simply as the current account: the balance of payments on goods and services plus net international transfer payments and factor income. This corresponds to rows 1, 2, and 3 in Table 34-2. In practice, row 1 of Table 34-2, amounting to −$476 billion in 2013, corresponds to the most important part of the current account: the balance of payments on goods and services, the difference between the value of exports and the value of imports during a given period.

A country’s balance of payments on goods and services is the difference between its exports and its imports during a given period.

The merchandise trade balance, or trade balance, is the difference between a country’s exports and imports of goods.

If you read news reports on the economy, you may well see references to another measure, the merchandise trade balance, sometimes referred to as the trade balance for short. It is the difference between a country’s exports and imports of goods alone—

A country’s balance of payments on financial account, or simply its financial account, is the difference between its sales of assets to foreigners and its purchases of assets from foreigners for a given period.

Transactions that involve the sale or purchase of assets, and therefore do create future liabilities, are considered part of the balance of payments on financial account, or the financial account for short, for a given period. This corresponds to row 4 in Table 34-2, which was $373 billion in 2013. (Until a few years ago, economists often referred to the financial account as the capital account. We’ll use the modern term, but you may run across the older term.)

So how does it all add up? The shaded rows of Table 34-2 show the bottom lines: the overall U.S. current account and financial account for 2013. As you can see, in 2013 the United States ran a current account deficit: the amount it paid to foreigners for goods, services, factors, and transfers was more than the amount it received. Simultaneously, it ran a financial account surplus: the value of the assets it sold to foreigners was more than the value of the assets it bought from foreigners.

In the 2013 official data, the U.S. current account deficit and financial account surplus didn’t exactly offset each other: the financial account surplus in 2013 was $27 billion smaller than the current account deficit. But that’s just a statistical error, reflecting the imperfection of official data. (The discrepancy may have reflected foreign purchases of U.S. assets that official data somehow missed.) In fact, it’s a basic rule of balance of payments accounting that the current account and the financial account must sum to zero:

or

CA = −FA

!worldview! FOR INQUIRING MINDS: GDP, GNP, and the Current Account

When we discussed national income accounting in Chapter 22, we derived the basic equation relating GDP to the components of spending:

Y = C + I + G + X − IM

where X and IM are exports and imports, respectively, of goods and services. But as we’ve learned, the balance of payments on goods and services is only one component of the current account balance. Why doesn’t the national income equation use the current account as a whole?

The answer is that gross domestic product, Y, is the value of goods and services produced domestically. So it doesn’t include international factor income and international transfers, two sources of income that are included in the calculation of the current account balance. The profits of Ford Motors U.K. aren’t included in the U.S. GDP, and the funds Latin American immigrants send home to their families aren’t subtracted from GDP.

Shouldn’t we have a broader measure that does include these sources of income? Actually, gross national product—

Why do economists use GDP rather than a broader measure? Two reasons. First, the original purpose of the national accounts was to track production rather than income. Second, data on international factor income and transfer payments are generally considered somewhat unreliable. So if you’re trying to keep track of movements in the economy, it makes sense to focus on GDP, which doesn’t rely on these unreliable data.

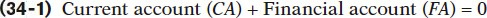

Why must Equation 34-

Money flows into the United States from the rest of the world as payment for U.S. exports of goods and services, as payment for the use of U.S.-owned factors of production, and as transfer payments. These flows (indicated by the lower green arrow) are the positive components of the U.S. current account. Money also flows into the United States from foreigners who purchase U.S. assets (as shown by the lower green arrow)—the positive component of the U.S. financial account.

At the same time, money flows from the United States to the rest of the world as payment for U.S. imports of goods and services, as payment for the use of foreign-

Equation 34-

Equation 34-

But what determines the current account and the financial account?

Modeling the Financial Account

A country’s financial account measures its net sales of assets to foreigners. There is, however, another way to think about the financial account: it’s a measure of capital inflows, of foreign savings that are available to finance domestic investment spending.

What determines these capital inflows?

Part of our explanation will have to wait for a little while because some international capital flows are carried out by governments and central banks, which sometimes act very differently from private investors. But we can gain insight into the motivations for capital flows that are the result of private decisions by using the loanable funds model we developed in Chapter 25. In using this model, we make two important simplifications:

We simplify the reality of international capital flows by assuming that all flows are in the form of loans. In reality, capital flows take many forms, including purchases of shares of stock in foreign companies and foreign real estate as well as direct foreign investment, in which companies build factories or acquire other productive assets abroad.

We also ignore the effects of expected changes in exchange rates, the relative values of different national currencies. We analyze the determination of exchange rates later in the chapter.

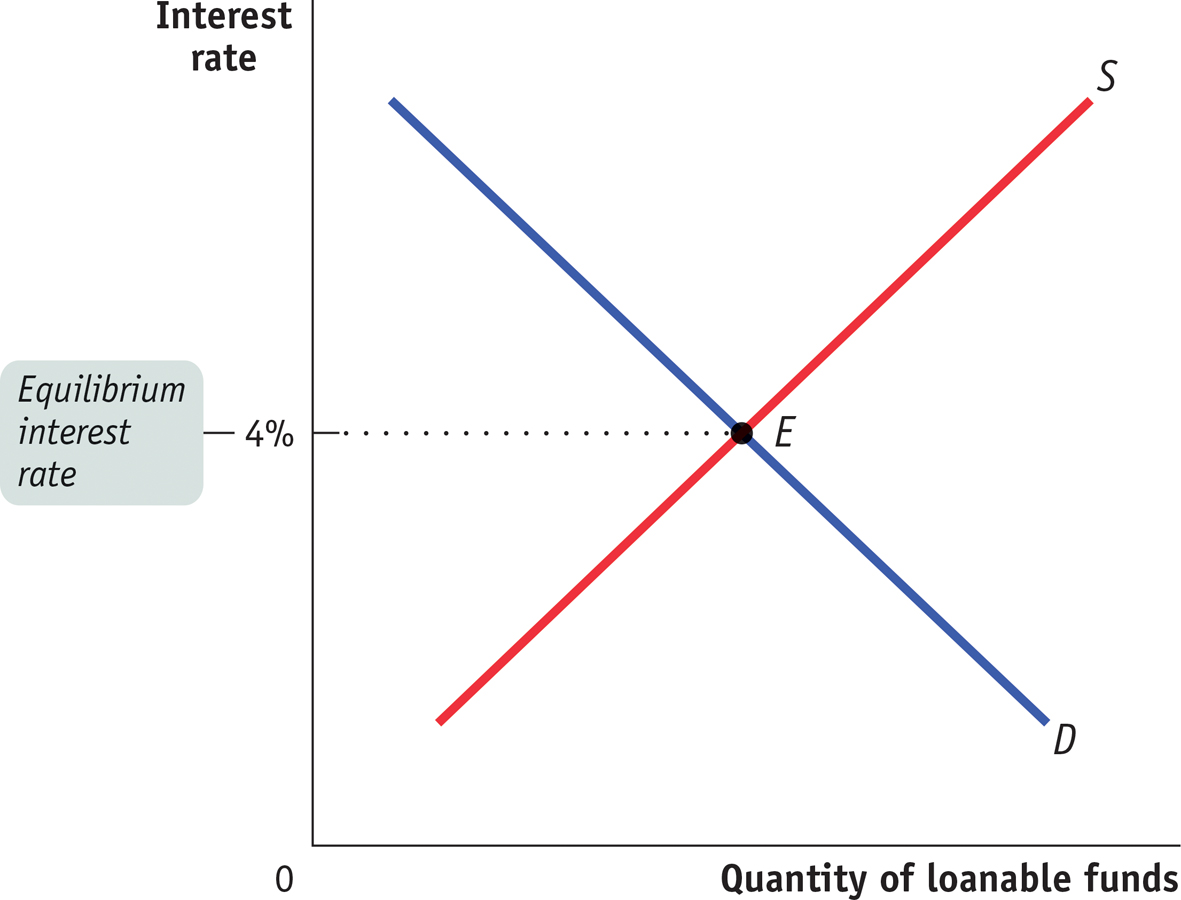

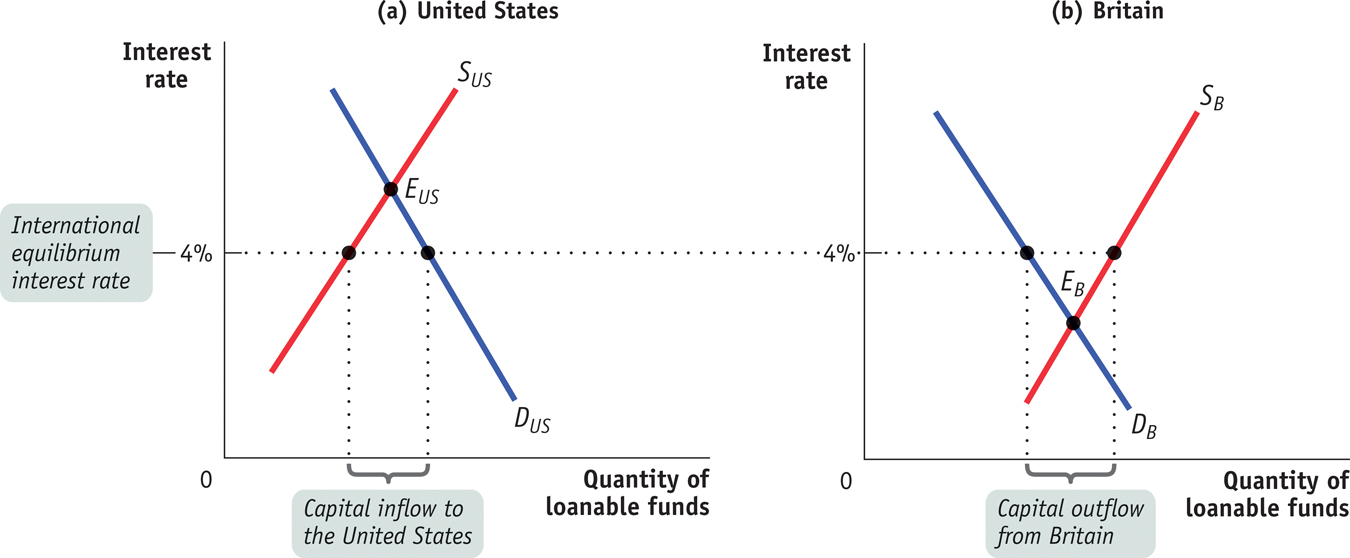

Figure 34-2 recaps the loanable funds model for a closed economy. Equilibrium corresponds to point E, at an interest rate of 4%, where the supply of loanable funds curve, S, intersects the demand for loanable funds curve, D. But if international capital flows are possible, this diagram changes and E may no longer be the equilibrium. We can analyze the causes and effects of international capital flows using Figure 34-3, which places the loanable funds market diagrams for two countries side by side.

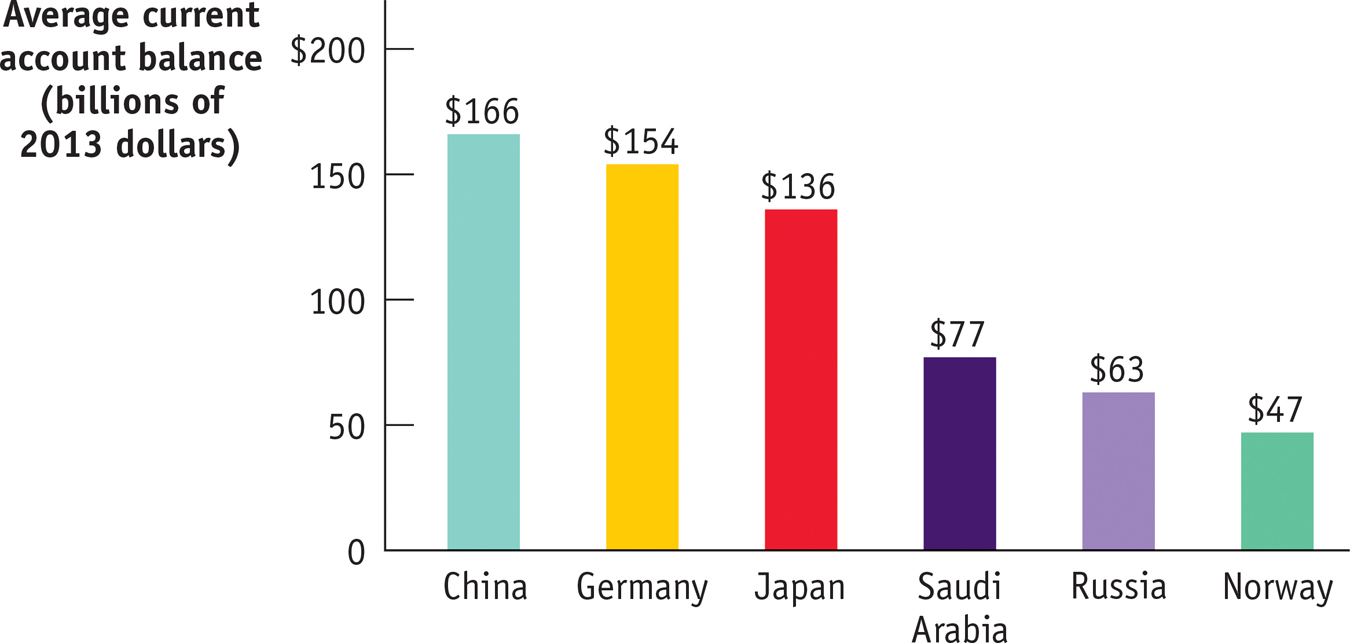

Big Surpluses

As we’ve seen, the United States generally runs a large deficit in its current account. In fact, America leads the world in its current account deficit; other countries run bigger deficits as a share of GDP, but they have much smaller economies, so the U.S. deficit is much bigger in absolute terms.

For the world as a whole, however, deficits on the part of some countries must be matched with surpluses on the part of other countries. So who are the surplus nations offsetting U.S. deficits, and what if anything do they have in common?

The accompanying figure shows the average current account surplus of the six countries that ran the largest surpluses over the period from 2000 to 2013. You may not be surprised to learn that China tops the list. As we explain later in this chapter, China’s surplus was largely due to its policy of keeping its currency weak relative to other currencies. But what about the others?

Japan and Germany run current account surpluses for more or less the same reasons: both are rich nations with high savings rates, giving them a lot of money to invest. Since some of that money goes abroad, the result is that they run deficits on the financial account and surpluses on current account.

The other three countries are all major oil exporters. (You may not think of Russia or Norway as “petro-

All in all, the surplus countries are a diverse group. If your picture of the world is simply one of American deficits versus Chinese surpluses, you’re missing a large part of the story.

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, 2014.

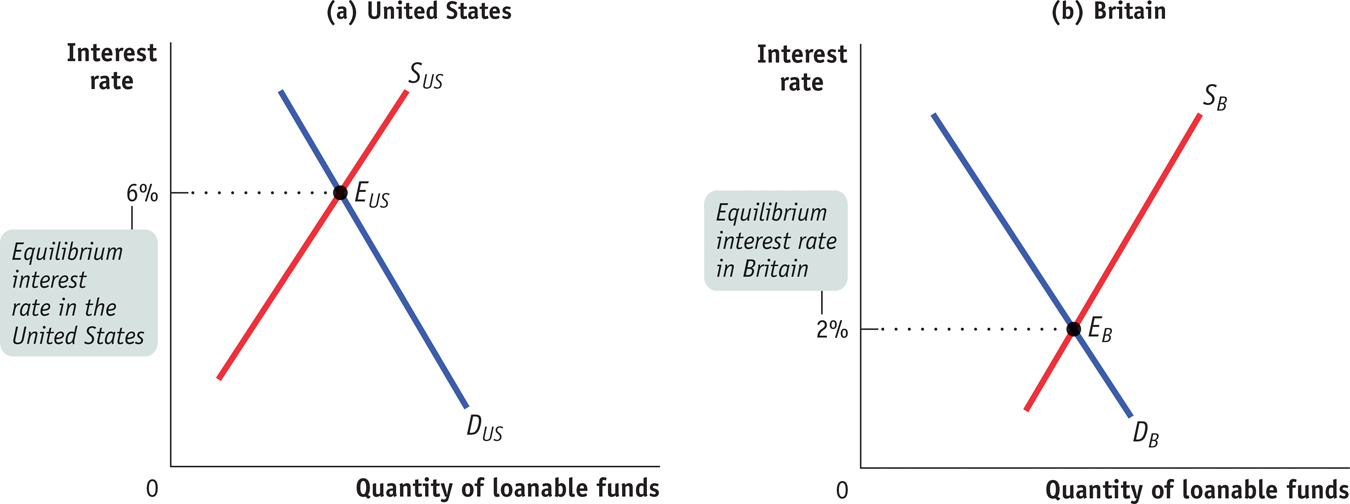

Figure 34-3 illustrates a world consisting of only two countries, the United States and Britain. Panel (a) shows the loanable funds market in the United States, where the equilibrium in the absence of international capital flows is at point EUS with an interest rate of 6%. Panel (b) shows the loanable funds market in Britain, where the equilibrium in the absence of international capital flows is at point EB with an interest rate of 2%.

Will the actual interest rate in the United States remain at 6% and that in Britain at 2%? Not if it is easy for British residents to make loans to Americans. In that case, British lenders, attracted by high U.S. interest rates, will send some of their loanable funds to the United States. This capital inflow will increase the quantity of loanable funds supplied to American borrowers, pushing the U.S. interest rate down. At the same time, it will reduce the quantity of loanable funds supplied to British borrowers, pushing the British interest rate up. So international capital flows will narrow the gap between U.S. and British interest rates.

Let’s further suppose that British lenders regard a loan to an American as being just as good as a loan to one of their own compatriots, and American borrowers regard a debt to a British lender as no more costly than a debt to an American lender. In that case, the flow of funds from Britain to the United States will continue until the gap between their interest rates is eliminated. In other words, when residents of the two countries believe that a foreign asset is as good as a domestic one and that a foreign liability is as good as a domestic one, then international capital flows will equalize the interest rates in the two countries.

Figure 34-4 shows an international equilibrium in the loanable funds markets where the equilibrium interest rate is 4% in both the United States and Britain. At this interest rate, the quantity of loanable funds demanded by American borrowers exceeds the quantity of loanable funds supplied by American lenders. This gap is filled by “imported” funds—

In short, international flows of capital are like international flows of goods and services. Capital moves from places where it would be cheap in the absence of international capital flows to places where it would be expensive in the absence of such flows.

Underlying Determinants of International Capital Flows

The open-

International differences in the demand for funds reflect underlying differences in investment opportunities. In particular, a country with a rapidly growing economy, other things equal, tends to offer more investment opportunities than a country with a slowly growing economy. So a rapidly growing economy typically—

The classic example, described in the upcoming Economics in Action, is the flow of capital from Britain to the United States, among other countries, between 1870 and 1914. During that era, the U.S. economy was growing rapidly as the population increased and spread westward and as the nation industrialized. This created a demand for investment spending on railroads, factories, and so on. Meanwhile, Britain had a much more slowly growing population, was already industrialized, and already had a railroad network covering the country. This left Britain with savings to spare, much of which were lent out to the United States and other New World economies.

International differences in the supply of funds reflect differences in savings across countries. These may be the result of differences in private savings rates, which vary widely among countries. For example, in 2010 gross private savings were 28.5% of Japan’s GDP but only 19.2% of U.S. GDP. They may also reflect differences in savings by governments. In particular, government budget deficits, which reduce overall national savings, can lead to capital inflows.

!worldview! FOR INQUIRING MINDS: A Global Savings Glut?

In the early years of the twenty-

In an influential speech early in 2005, Ben Bernanke—

What caused this global savings glut? According to Bernanke, the main cause was the series of financial crises that began in Thailand in 1997; ricocheted across much of Asia; then hit Russia in 1998, Brazil in 1999, and Argentina in 2002. The ensuing fear and economic devastation led to a fall in investment spending and a rise in savings in a number of relatively poor countries. As a result, a number of these countries, which had previously been the recipients of capital inflows from advanced countries like the United States, began experiencing large capital outflows. For the most part, the capital flowed to the United States, perhaps because “the depth and sophistication of the country’s financial markets” made it an attractive destination.

When Bernanke gave his speech, it was viewed as reassuring: basically, he argued that the United States was responding in a sensible way to the availability of cheap money in world financial markets. Later, however, it would become clear that the cheap money from abroad helped fuel a housing bubble, which caused widespread financial and economic damage when it burst.

Two-Way Capital Flows

The loanable funds model helps us understand the direction of net capital flows—

The answer to this question is that in the real world, as opposed to the simple model we’ve just learned, there are other motives for international capital flows besides seeking a higher rate of interest.

Individual investors often seek to diversify against risk by buying stocks in a number of countries. Stocks in Europe may do well when stocks in the United States do badly, or vice versa, so investors in Europe try to reduce their risk by buying some U.S. stocks, as investors in the United States try to reduce their risk by buying some European stocks. The result is capital flows in both directions.

Meanwhile, corporations often engage in international investment as part of their business strategy—

Finally, some countries, including the United States, are international banking centers: people from all over the world put money in U.S. financial institutions, which then invest many of those funds overseas.

The result of these two-

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: The Golden Age of Capital Flows

The Golden Age of Capital Flows

Technology, it’s often said, shrinks the world. Jet planes have put most of the world’s cities within a few hours of one another; modern telecommunications transmit information instantly around the globe. So you might think that international capital flows must now be larger than ever.

But if capital flows are measured as a share of world savings and investment, that belief turns out not to be true. The golden age of capital flows actually preceded World War I—

These capital flows went mainly from European countries, especially Britain, to what were then known as zones of recent settlement, countries that were attracting large numbers of European immigrants. Among the big recipients of capital inflows were Australia, Argentina, Canada, and the United States.

The large capital flows reflected differences in investment opportunities. Britain, a mature industrial economy with limited natural resources and a slowly growing population, offered relatively limited opportunities for new investment. The zones of recent settlement, with rapidly growing populations and abundant natural resources, offered investors a higher return and attracted capital inflows. Estimates suggest that over this period Britain sent about 40% of its savings abroad, largely to finance railroads and other large projects. No country has matched that record in modern times.

Why can’t we match the capital flows of our great-

During the golden age of capital flows, capital movements were complementary to population movements: the big recipients of capital from Europe were also places to which large numbers of Europeans were moving. These large-

The other factor that has changed is political risk. Modern governments often limit foreign investment because they fear it will diminish their national autonomy. And due to political or security concerns, governments sometimes seize foreign property, a risk that deters investors from sending more than a relatively modest share of their wealth abroad. In the nineteenth century such actions were rare, partly because some major destinations of investment were still European colonies, partly because in those days governments had a habit of sending troops and gunboats to enforce the claims of their investors.

Quick Review

The balance of payments accounts, which track a country’s international transactions, are composed of the balance of payments on current account, or the current account, plus the balance of payments on financial account, or the financial account. The most important component of the current account is the balance of payments on goods and services, which itself includes the merchandise trade balance, or the trade balance.

Because the sources of payments must equal the uses of payments, the current account plus the financial account sum to zero.

Capital moves to equalize interest rates across countries. Countries can experience two-

way capital flows because factors other than interest rates also affect investors’ decisions. Capital flows reflect international differences in savings behavior and in investment opportunities.

34-1

Question 19.1

Which of the balance of payments accounts do the following events affect?

Boeing, a U.S.-based company, sells a newly built airplane to China.

Chinese investors buy stock in Boeing from Americans.

A Chinese company buys a used airplane from American Airlines and ships it to China.

A Chinese investor who owns property in the United States buys a corporate jet, which he will keep in the United States so he can travel around America.

Question 19.2

What effect do you think the collapse of the U.S. housing bubble and the ensuing recession had on international capital flows into the United States?

Solutions appear at back of book.