Exchange Rates and Macroeconomic Policy

When the euro was created in 1999, there were celebrations across the nations of Europe—

Why did Britain say no? Part of the answer was national pride: if Britain gave up the pound, it would also have to give up currency that bears the portrait of the queen. But there were also serious economic concerns about giving up the pound in favor of the euro. British economists who favored adoption of the euro argued that if Britain used the same currency as its neighbors, the country’s international trade would expand and its economy would become more productive. But other economists pointed out that adopting the euro would take away Britain’s ability to have an independent monetary policy and might lead to macroeconomic problems.

As this discussion suggests, the fact that modern economies are open to international trade and capital flows adds a new level of complication to our analysis of macroeconomic policy. Let’s look at three policy issues raised by open-

1. Devaluation and Revaluation of Fixed Exchange Rates

Historically, fixed exchange rates haven’t been permanent commitments. Sometimes countries with a fixed exchange rate switch to a floating rate. In other cases, they retain a fixed rate but change the target exchange rate. Such adjustments in the target were common during the Bretton Woods era described in the preceding For Inquiring Minds. For example, in 1967 Britain changed the exchange rate of the pound against the U.S. dollar from US$2.80 per £1 to US$2.40 per £1. A modern example is Argentina, which maintained a fixed exchange rate against the dollar from 1991 to 2001 but switched to a floating exchange rate at the end of 2001.

A devaluation is a reduction in the value of a currency that is set under a fixed exchange rate regime.

A reduction in the value of a currency that is set under a fixed exchange rate regime is called a devaluation. As we’ve already learned, a depreciation is a downward move in a currency. A devaluation is a depreciation that is due to a revision in a fixed exchange rate target. An increase in the value of a currency that is set under a fixed exchange rate regime is called a revaluation.

A revaluation is an increase in the value of a currency that is set under a fixed exchange rate regime.

A devaluation, like any depreciation, makes domestic goods cheaper in terms of foreign currency, which leads to higher exports. At the same time, it makes foreign goods more expensive in terms of domestic currency, which reduces imports. The effect is to increase the balance of payments on current account. Similarly, a revaluation makes domestic goods more expensive in terms of foreign currency, which reduces exports, and makes foreign goods cheaper in domestic currency, which increases imports. So a revaluation reduces the balance of payments on current account.

Devaluations and revaluations serve two purposes under fixed exchange rates. First, they can be used to eliminate shortages or surpluses in the foreign exchange market. For example, in 2010 some economists and politicians were urging China to revalue the yuan because they believed that China’s exchange rate policy unfairly aided Chinese exports.

Second, devaluation and revaluation can be used as tools of macroeconomic policy. A devaluation, by increasing exports and reducing imports, increases aggregate demand. So a devaluation can be used to reduce or eliminate a recessionary gap. A revaluation has the opposite effect, reducing aggregate demand. So a revaluation can be used to reduce or eliminate an inflationary gap.

2. Monetary Policy Under Floating Exchange Rates

Under a floating exchange rate regime, a country’s central bank retains its ability to pursue independent monetary policy: it can increase aggregate demand by cutting the interest rate or decrease aggregate demand by raising the interest rate. But the exchange rate adds another dimension to the effects of monetary policy. To see why, let’s return to the hypothetical country of Genovia and ask what happens if the central bank cuts the interest rate.

Just as in a closed economy, a lower interest rate leads to higher investment spending and higher consumer spending. But the decline in the interest rate also affects the foreign exchange market. Foreigners have less incentive to move funds into Genovia because they will receive a lower interest rate on their loans. As a result, they have less need to exchange U.S. dollars for genos, so the demand for genos falls. At the same time, Genovians have more incentive to move funds abroad because the interest rate on loans at home has fallen, making investments outside the country more attractive. As a result, they need to exchange more genos for U.S. dollars, so the supply of genos rises.

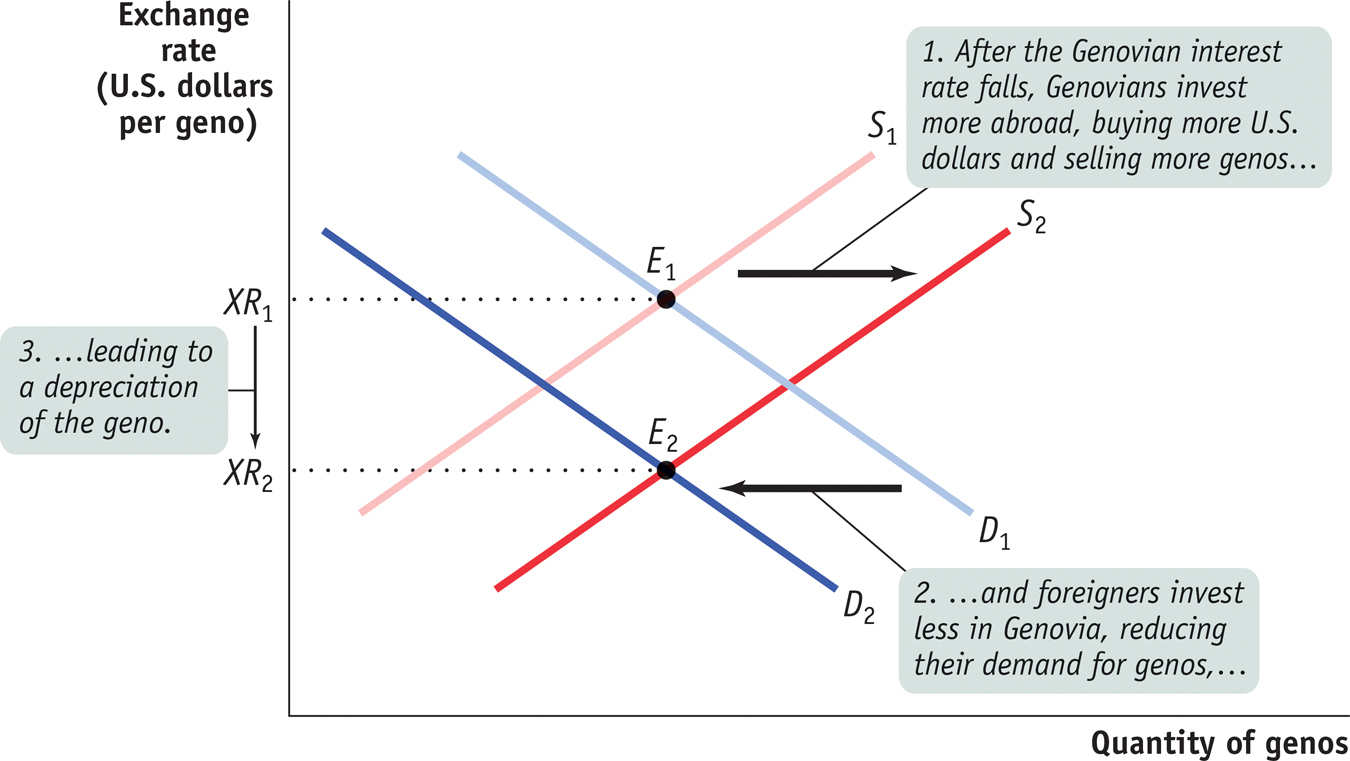

Figure 34-12 shows the effect of an interest rate reduction on the foreign exchange market. The demand curve for genos shifts leftward, from D1 to D2, and the supply curve shifts rightward, from S1 to S2. The equilibrium exchange rate, as measured in U.S. dollars per geno, falls from XR1 to XR2. That is, a reduction in the Genovian interest rate causes the geno to depreciate.

The depreciation of the geno, in turn, affects aggregate demand. We’ve already seen that a devaluation—

In other words, monetary policy under floating rates has effects beyond those we’ve described in looking at closed economies. In a closed economy, a reduction in the interest rate leads to a rise in aggregate demand because it leads to more investment spending and consumer spending. In an open economy with a floating exchange rate, the interest rate reduction leads to increased investment spending and consumer spending, but it also increases aggregate demand in another way: it leads to a currency depreciation, which increases exports and reduces imports, and further increases aggregate demand.

3. International Business Cycles

Up to this point, we have discussed macroeconomics, even in an open economy, as if all demand shocks originate from the domestic economy. In reality, however, economies sometimes face shocks coming from abroad. For example, recessions in the United States have historically led to recessions in Mexico.

The key point is that changes in aggregate demand affect the demand for goods and services produced abroad as well as at home: other things equal, a recession leads to a fall in imports and an expansion leads to a rise in imports. And one country’s imports are another country’s exports. This link between aggregate demand in different national economies is one reason business cycles in different countries sometimes—

The extent of this link depends, however, on the exchange rate regime. To see why, think about what happens if a recession abroad reduces the demand for Genovia’s exports. A reduction in foreign demand for Genovian goods and services is also a reduction in demand for genos in the foreign exchange market. If Genovia has a fixed exchange rate, it responds to this decline with exchange market intervention. But if Genovia has a floating exchange rate, the geno depreciates. Because Genovian goods and services become cheaper to foreigners when the demand for exports falls, the quantity of goods and services exported doesn’t fall by as much as it would under a fixed rate. At the same time, the fall in the geno makes imports more expensive to Genovians, leading to a fall in imports. Both effects limit the decline in Genovia’s aggregate demand compared to what it would have been under a fixed exchange rate.

One of the virtues of a floating exchange rate, according to advocates of such exchange rates, is that they help insulate countries from recessions originating abroad. This theory looked pretty good in the early 2000s: Britain, with a floating exchange rate, managed to stay out of a recession that affected the rest of Europe, and Canada, which also has a floating rate, suffered a less severe recession than the United States.

In 2008, however, a financial crisis that began in the United States led to a recession in virtually every country. In this case, it appears that the international linkages among financial markets were much stronger than any insulation from overseas disturbances provided by floating exchange rates.

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: The Little Currency That Could

The Little Currency That Could

In 2008 Iceland—

But there was one big difference between Iceland and Greece (aside from the weather): Greece no longer had its own currency, because it had adopted the euro, whereas Iceland, tiny though it was, still had its own currency, the krona (plural kronur)—and Icelandic wages are set in kronur, not euros or dollars.

This meant that the process of cutting wages was very different in Iceland than it was in euro-

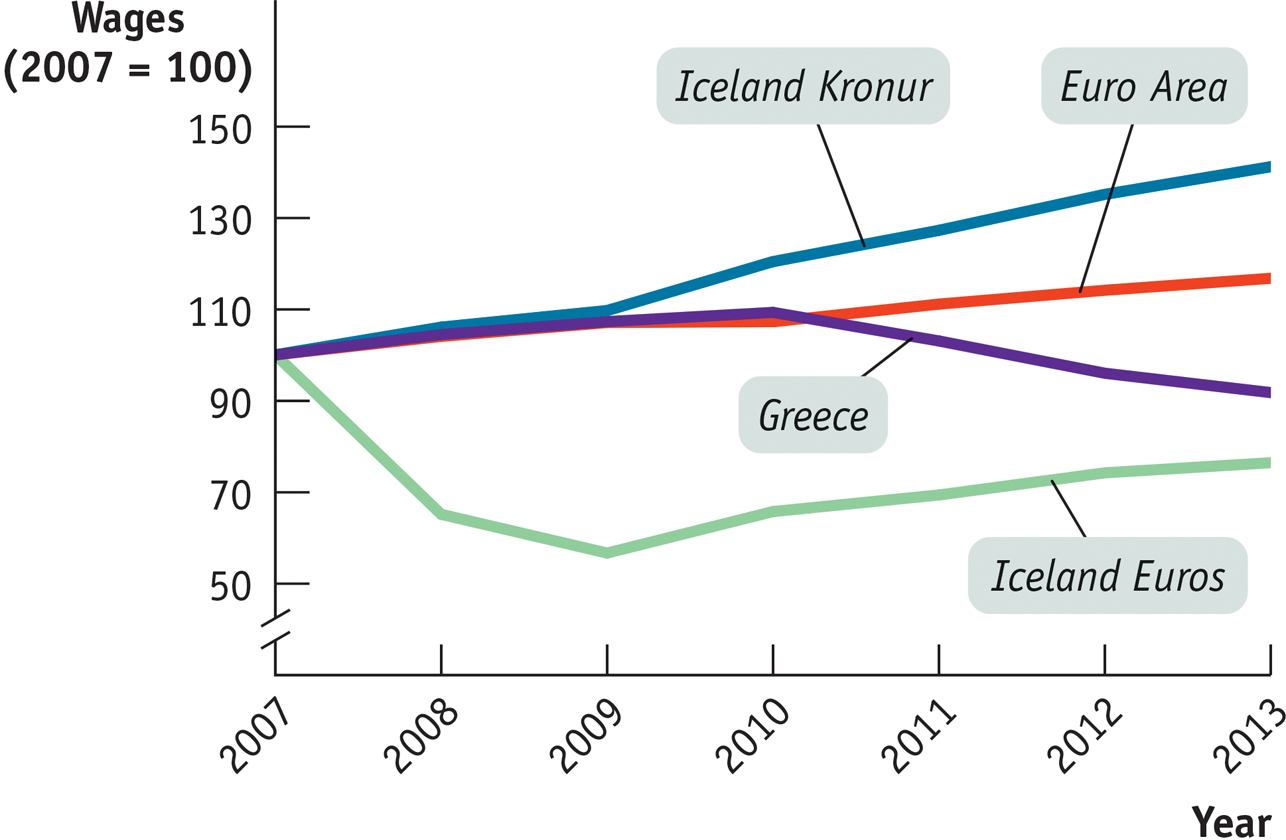

Figure 34-13 shows how the different options played out. One line shows average wages in the euro area as a whole, with 2007 = 100, while another line shows Greek wages over the same period. As you can see, Greece did manage to cut wages gradually over time while wages in other European nations rose, so the Greek economy gradually became more competitive. It was, however, a slow and extremely painful process.

The other two lines show Iceland’s story. One line shows wages in kronur—

Overall, Iceland’s experience was an object lesson in the advantages of having your own currency—

Quick Review

Countries can change fixed exchange rates. Devaluation or revaluation can help reduce surpluses or shortages in the foreign exchange market and can increase or reduce aggregate demand.

In an open economy with a floating exchange rate, interest rates also affect the exchange rate, and so monetary policy affects aggregate demand through the effects of the exchange rate on imports and exports.

Because one country’s imports are another country’s exports, business cycles are sometimes synchronized across countries. However, floating exchange rates may reduce this link.

34-4

Question 19.6

Look at the data in Figure 34-11. Where do you see devaluations and revaluations of the franc against the mark?

Question 19.7

In the late 1980s Canadian economists argued that the high interest rate policies of the Bank of Canada weren’t just causing high unemployment—

they were also making it hard for Canadian manufacturers to compete with the United States. Explain this complaint, using our analysis of how monetary policy works under floating exchange rates.

Solutions appear at back of book.

A Yen for Japanese Cars

At the end of 2012 Shinzo Abe, a veteran politician, became prime minister of Japan. He surprised most observers by seeking radical changes in Japan’s economic policy. With Japanese inflation running at a slightly negative rate, he oversaw a dramatic easing of monetary policy. The Bank of Japan greatly increased the monetary base and assured investors that it would do whatever it took to raise inflation to 2%. Two years later, the overall results of this policy were still uncertain, but one effect was a much weaker yen. For most of 2012 the yen traded at around 80 per dollar, but by late 2014 the exchange rate was around 115 yen per dollar, a 44% depreciation.

The weaker yen, in turn, made some Japanese businesses happy—

However, the benefits weren’t equally spread: while Toyota was doing fairly well, Subaru was really taking off. Why? Well, over the years Toyota has moved the majority of its production out of Japan, operating numerous plants in the United States, Mexico, Canada, and various other countries. Subaru, which is a smaller company with a more limited product range, still mainly produces in Japan.

So while you can argue that what’s good for Japan is good for Japanese auto companies—

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 19.8

QbMXkB8UjakiKjpK1gci42KaHzk9OwYt7MxySoC/swNdNlGY4t71qRPG0x5BksCnWhy would Abenomics lead to a weaker yen?Question 19.9

eTtE1i6z4cqlOoQA0fV18Ojrin/Fjpbm6zOTQPEkQSdmd8b78+oo4Y9/8ic8vZwquLWfjx7pw1IgogwiFv1I2jpgibzI5elxWhy is a weaker yen good for the profits of Japanese auto companies?Question 19.10

p3qCGDnS0AUr3Jk7vPnnhiKna2Uqy99a91nrRT91dvY+/H3ksWGFSGXftSY=Why does Subaru gain more than Toyota?