16.10 Business Case

473

BUSINESS CASE

BUSINESS CASE

How Boeing Got Better

When we think about innovation and technological progress, we tend to focus on the big, dramatic changes: cars replacing horses and buggies, electric lightbulbs replacing gaslights, computers replacing adding machines and typewriters. A lot of progress, however, is incremental and almost invisible to most people—

The Boeing 707, introduced in 1957, was the first commercially successful jetliner, and for a number of years it ruled the skies. When the Beatles made their famous 1964 arrival in America, it was a 707 that brought them there. So what did the 707 look like? What’s striking about it, from a modern perspective, is how ordinary it appears. Basically, it looks like a jet airliner. If you walked past one today, and nobody told you it was an antique, you probably wouldn’t notice; 50-

Furthermore, the visible performance of modern jets, like the Boeing 777 or the even more advanced 787, isn’t that much better than that of the old 707. They only fly slightly faster; once you take extra security and flight delays into account, traveling from London to New York probably takes more time now than in 1964. It’s nice to have a selection of movies (although there may not be anything you want to watch), and business-

Yet Boeing’s modern jets (and those of its main competitor, Airbus) are vastly more efficient than jets half a century ago—

The answer is, things passengers can’t see. Most important, there has been a drastic improvement in fuel efficiency, with modern planes using less than a third as much fuel per passenger-

The moral is that the technological progress that drives growth is much broader and more powerful than meets the eye. Even when things look more or less the same, there is often enormous change beneath the surface.

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

A modern jet airliner does pretty much the same thing as an airliner from the 1960s: it gets you there from here, in about the same time. Where’s the technological progress?

Do scientific advances play any role in the progress we’ve described? Explain.

Some travelers complain that the flight experience has gone downhill. Does this refute the claim of technological progress?

474

BUSINESS CASE

BUSINESS CASE

Slow Steaming

The global economic slump of 2008–2009 took a toll on almost everyone. By 2011, however, the acute crisis was receding in the rearview mirror. Unemployment remained high in wealthy countries, but the world economy as a whole was growing fairly fast, and so were corporate profits.

One industry that wasn’t doing well, however, was shipping. A 2012 report from the Boston Consulting Group declared that executives in the container-

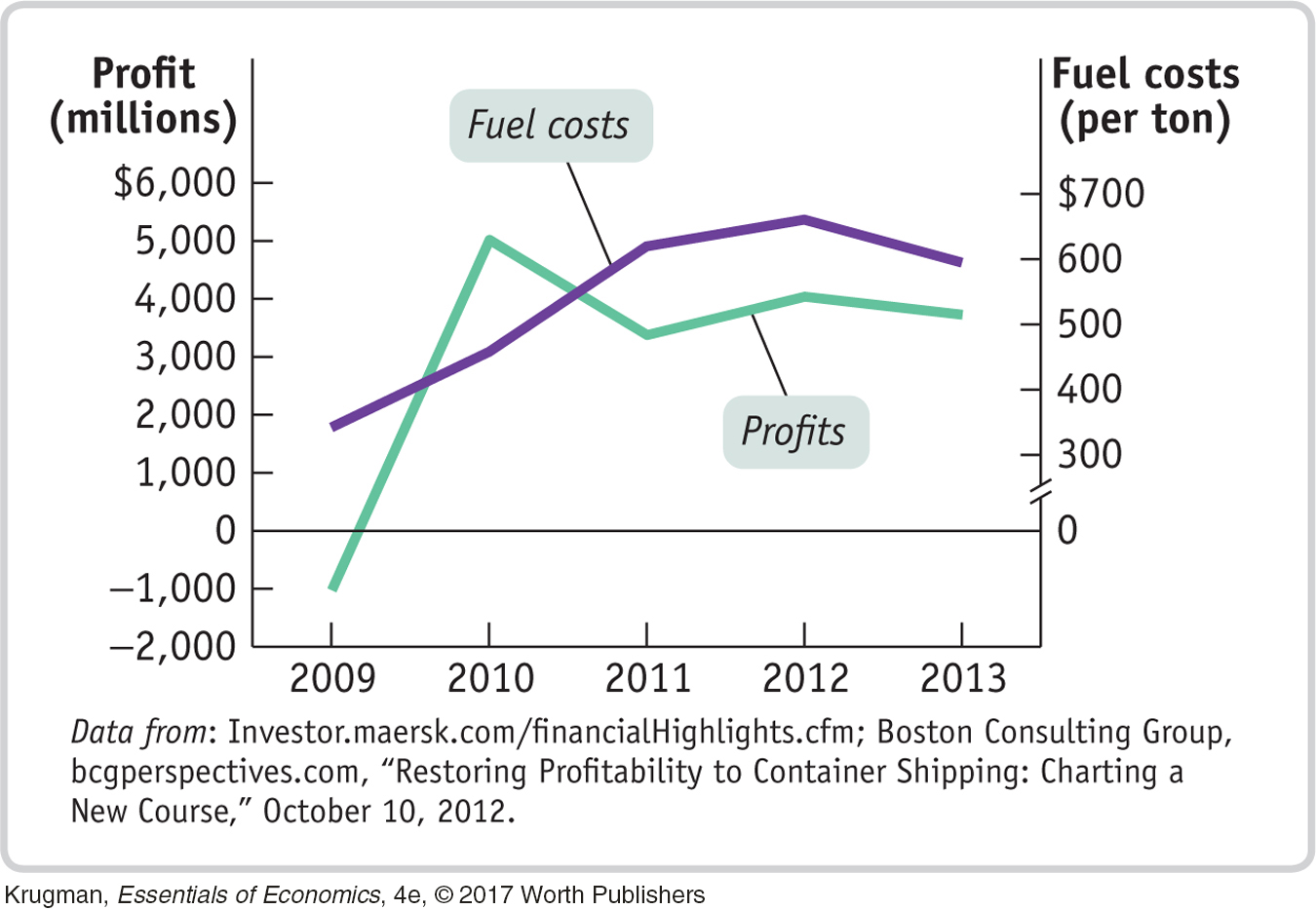

Why was 2011 a bad year to be in the shipping business? The answer is that while world trade and hence the overall demand for shipping were rising, there was a surge in oil prices. This was bad news for shippers, for whom the cost of fuel oil is a major expense. As you can see in the figure, profits temporarily increased immediately after the Great Recession when fuel costs were low. But that changed near the end of 2010, as the price of fuel started to rise. And in 2011, as fuel prices spiked at almost $700 per ton, profits fell by more than $1 billion.

One consequence of the oil price shock was a literal slowdown in world trade: shippers turned to slow steaming, in which ships get somewhat better fuel economy by traveling more slowly, typically 17 knots rather than their usual 20. Some carriers even went to super-

Maersk and other shippers did better in 2012, as oil prices receded somewhat. But the troubles of 2011 were a reminder that there is more than one way to get into economic trouble.

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

How did Maersk’s problem in 2011 relate to our analysis of the causes of recessions?

The Fed had to make a choice between fighting two evils in early 2008. How would that choice affect Maersk compared with, say, a company producing a service without expensive raw-

material inputs, like health care? In 2011, the world economy was holding up fairly well, but Europe was sliding back into recession. What do you think was happening to the business of intra-

European transport (which mainly goes by truck, not ship)? Why?