19.10 Business Case

566

BUSINESS CASE

BUSINESS CASE

Here Comes the Sun

The Solana power plant, which opened in 2013, covers 3 square miles of the Arizona desert in Gila Bend, about 70 miles from Phoenix. Whereas most solar installations rely on photovoltaic panels that convert light directly into electricity, Solana uses a system of mirrors to concentrate the sun’s heat on black pipes, which convey that heat to tanks of molten salt. The heat in the salt is, in turn, used to generate electricity. The advantage of this arrangement is that the plant can keep generating power long after the sun has gone down, greatly enhancing its efficiency.

Solana is one of only a small number of concentrated thermal solar plants operating or under construction. Solar power has been rapidly rising in importance, with the amount of electricity generated by solar increasing over 400% between 2008 and 2015. There are a number of reasons for this sudden rise, but the Obama stimulus—

While Solana is a good example of stimulus spending at work, it is also a good example of why such spending tends to be politically difficult. There were many protests over federal loans to a non-

In terms of the goals of the stimulus, however, Solana seems to have done what it was supposed to: it generated jobs at a time when borrowing was cheap and many construction workers were unemployed.

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

How did the political reaction to government funding for the Solana project differ from the reaction to more conventional government spending projects such as roads and schools? What does the case tell us about how to assess the value of a fiscal stimulus project?

In the chapter we talked about the problem of lags in discretionary fiscal policy. What does the Solana case tell us about this issue?

Is the depth of a recession a good or a bad time to undertake an energy project? Why or why not?

567

BUSINESS CASE

BUSINESS CASE

The Perfect Gift: Cash or a Gift Card?

It’s always nice when someone shows his or her appreciation by giving you a gift. Over the past few years, more and more people have been showing their appreciation by giving gift cards, prepaid plastic cards issued by a retailer that can be redeemed for merchandise. The best-

What could be more simple and useful than allowing the recipient to choose what he or she wants? And isn’t a gift card more personal than cash or a check?

Yet several websites are now making a profit from the fact that gift card recipients are often willing to sell their cards at a discount—

Cardpool.com is one such site. At the time of writing, it offers to pay cash to a seller of a Whole Foods gift card equivalent to 88% of the card’s face value. For example, the seller of a card with a value of $100 would receive $88 in cash. But it offers cash equal to only 70% of a Gap card’s face value. Cardpool.com profits by reselling the card at a premium over what it paid; for example, it buys a Whole Foods card for 88% of its face value and then resells it for 97% of its face value.

Many consumers will sell at a sizable discount to turn gift cards into cash. But retailers promote the use of gift cards over cash because much of the value of gift cards issued never gets used, a phenomenon known as breakage.

How does breakage occur? People lose cards. Or they spend only $47 of a $50 gift card, and never return to the store to spend that last $3. Also, retailers impose fees on the use of cards or make them subject to expiration dates, which customers forget about. And if a retailer goes out of business, the value of outstanding gift cards disappears with it.

In addition to breakage, retailers benefit when customers intent on using up the value of their gift card find that it is too difficult to spend exactly the amount of the card. Instead, they end up spending more than the card’s face value, sometimes even more than they would have without the gift card.

Gift cards are so beneficial to retailers that instead of rewarding customer loyalty with rebate checks (once a common practice), they have switched to dispensing gift cards. As one commentator noted in explaining why retailers prefer gift cards to rebate checks, “Nobody neglects to spend cash.”

However, the future may not be quite so profitable for gift card issuers. Hard economic times have made consumers more careful about spending down their cards. And legislation enacted in 2009 requires that cards remain valid for at least five years. As a result, breakage has fallen sharply, although it still amounts to more than $1 billion a year.

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Why are gift card owners willing to sell their cards for a cash amount less than their face value?

Why do gift cards for retailers like Walmart, Home Depot, and Whole Foods sell for a smaller discount than those for retailers like the Gap and Aeropostale?

Use your answer from Question 2 to explain why cash never “sells” at a discount.

Explain why retailers prefer to reward loyal customers with gift cards instead of rebate checks.

Recent legislation restricted retailers’ ability to impose fees and expiration dates on their gift cards and mandated greater disclosure of their terms. Why do you think Congress enacted this legislation?

568

BUSINESS CASE

BUSINESS CASE

PIMCO Bets on Cheap Money

Pacific Investment Management Company, generally known as PIMCO, is one of the world’s largest investment companies. Among other things, it runs PIMCO Total Return, the world’s largest mutual fund. Bill Gross, who headed PIMCO from 1971 until 2014, was legendary for his ability to predict trends in financial markets, especially bond markets, where PIMCO does much of its investing.

In the fall of 2009, Gross decided to put more of PIMCO’s assets into long-

What lay behind PIMCO’s bet? Gross explained the firm’s thinking in his September 2009 commentary. He suggested that unemployment was likely to stay high and inflation low. “Global policy rates,” he asserted—

PIMCO’s view was in sharp contrast to those of other investors: Morgan Stanley expected long-

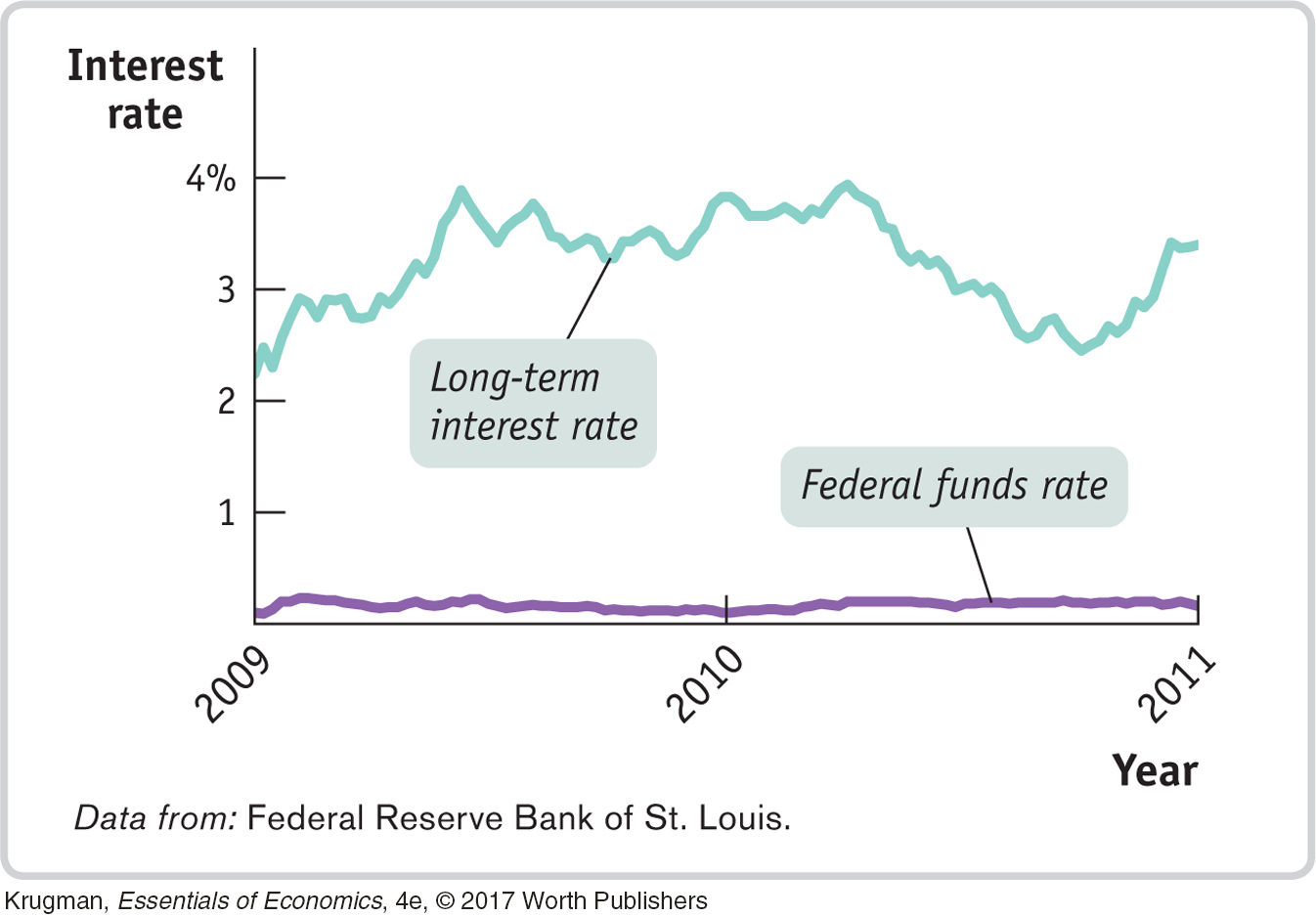

Who was right? PIMCO, mostly. As the figure shows, the federal funds rate stayed near zero, and long-

Bill Gross’s foresight, however, was a lot less accurate in 2011. Anticipating a significantly stronger U.S. economy by mid-

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Why did PIMCO’s view that unemployment would stay high and inflation low lead to a forecast that policy interest rates would remain low for an extended period?

Why would low policy rates suggest low long-

term interest rates? hat might have caused long-

term interest rates to rise in late 2010, even though the federal funds rate was still zero?