Monopoly, Oligopoly, and Public Policy

It’s good to be a monopolist, but it’s not so good to be a monopolist’s customer. A monopolist, by reducing output and raising prices, benefits at the expense of consumers. But buyers and sellers always have conflicting interests. Is the conflict of interest under monopoly any different than it is under perfect competition?

The answer is yes, because monopoly is a source of inefficiency: the losses to consumers from monopoly behavior are larger than the gains to the monopolist. Because monopoly leads to net losses for the economy, governments often try either to prevent the emergence of monopolies or to limit their effects. In this section, we will see why monopoly leads to inefficiency and examine the policies governments adopt in an attempt to prevent this inefficiency.

Welfare Effects of Monopoly

By restricting output below the level at which marginal cost is equal to the market price, a monopolist increases its profit but hurts consumers. To assess whether this is a net benefit or loss to society, we must compare the monopolist’s gain in profit to the loss in consumer surplus. And what we learn is that the loss in consumer surplus is larger than the monopolist’s gain. Monopoly causes a net loss for society.

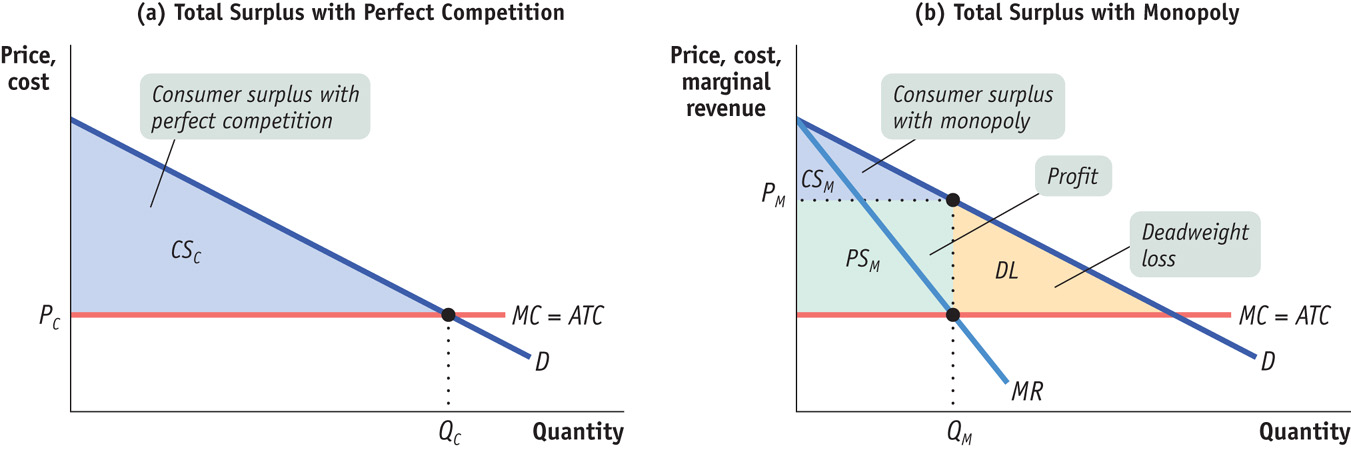

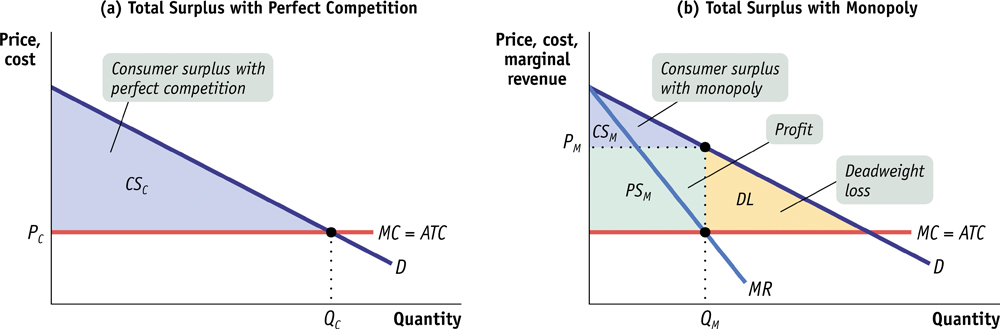

To see why, let’s return to the case where the marginal cost curve is horizontal, as shown in the two panels of Figure 8-8. Here the marginal cost curve is MC, the demand curve is D, and, in panel (b), the marginal revenue curve is MR.

Panel (a) shows what happens if this industry is perfectly competitive. Equilibrium output is QC; the price of the good, PC, is equal to marginal cost, and marginal cost is also equal to average total cost because there is no fixed cost and marginal cost is constant. Each firm is earning exactly its average total cost per unit of output, so there is no profit and no producer surplus in this equilibrium. The consumer surplus generated by the market is equal to the area of the blue-shaded triangle CSC shown in panel (a). Since there is no producer surplus when the industry is perfectly competitive, CSC also represents the total surplus.

259

Panel (b) shows the results for the same market, but this time assuming that the industry is a monopoly. The monopolist produces the level of output QM, at which marginal cost is equal to marginal revenue, and it charges the price PM. The industry now earns profit—which is also the producer surplus—equal to the area of the green rectangle, PSM. Note that this profit is surplus that has been captured from consumers as consumer surplus shrinks to the area of the blue triangle, CSM.

By comparing panels (a) and (b), we see that in addition to the redistribution of surplus from consumers to the monopolist, another important change has occurred: the sum of profit and consumer surplus—total surplus—is smaller under monopoly than under perfect competition. That is, the sum of CSM and PSM in panel (b) is less than the area CSC in panel (a). In Chapter 5, we analyzed how taxes generated deadweight loss to society. Here we show that monopoly creates a deadweight loss to society equal to the area of the yellow triangle, DL. So monopoly produces a net loss for society.

This net loss arises because some mutually beneficial transactions do not occur. There are people for whom an additional unit of the good is worth more than the marginal cost of producing it but who don’t consume it because they are not willing to pay PM.

If you recall our discussion of the deadweight loss from taxes in Chapter 5 you will notice that the deadweight loss from monopoly looks quite similar. Indeed, by driving a wedge between price and marginal cost, monopoly acts much like a tax on consumers and produces the same kind of inefficiency.

So monopoly hurts the welfare of society as a whole and is a source of market failure. Is there anything government policy can do about it?

Preventing Monopoly

Policy toward monopoly depends crucially on whether or not the industry in question is a natural monopoly, one in which increasing returns to scale ensure that a bigger producer has lower average total cost. If the industry is not a natural monopoly, the best policy is to prevent monopoly from arising or break it up if it already exists. Let’s focus on that case first, then turn to the more difficult problem of dealing with natural monopoly.

The De Beers monopoly on diamonds didn’t have to happen. Diamond production is not a natural monopoly: the industry’s costs would be no higher if it consisted of a number of independent, competing producers (as is the case, for example, in gold production).

So if the South African government had been worried about how a monopoly would have affected consumers, it could have blocked Cecil Rhodes in his drive to dominate the industry or broken up his monopoly after the fact. Today, governments often try to prevent monopolies from forming and break up existing ones.

De Beers is a rather unique case: for complicated historical reasons, it was allowed to remain a monopoly. But over the last century, most similar monopolies have been broken up. The most celebrated example in the United States is Standard Oil, founded by John D. Rockefeller in 1870. By 1878 Standard Oil controlled almost all U.S. oil refining; but in 1911 a court order broke the company into a number of smaller units, including the companies that later became Exxon and Mobil (and more recently merged to become ExxonMobil).

260

The government policies used to prevent or eliminate monopolies are known as antitrust policy, which we will discuss shortly.

Natural Monopoly

Breaking up a monopoly that isn’t natural is clearly a good idea: the gains to consumers outweigh the loss to the producer. But it’s not so clear whether a natural monopoly, one in which a large producer has lower average total costs than small producers, should be broken up, because this would raise average total cost. For example, a town government that tried to prevent a single company from dominating local gas supply—which, as we’ve discussed, is almost surely a natural monopoly—would raise the cost of providing gas to its residents.

Yet even in the case of a natural monopoly, a profit-maximizing monopolist acts in a way that causes inefficiency—it charges consumers a price that is higher than marginal cost and, by doing so, prevents some potentially beneficial transactions. Also, it can seem unfair that a firm that has managed to establish a monopoly position earns a large profit at the expense of consumers.

What can public policy do about this? There are two common answers.

In public ownership of a monopoly, the good is supplied by the government or by a firm owned by the government.

Public Ownership In many countries, the preferred answer to the problem of natural monopoly has been public ownership. Instead of allowing a private monopolist to control an industry, the government establishes a public agency to provide the good and protect consumers’ interests. In Britain, for example, telephone service was provided by the state-owned British Telecom before 1984, and airline travel was provided by the state-owned British Airways before 1987. (These companies still exist, but they have been privatized, competing with other firms in their respective industries.)

There are some examples of public ownership in the United States. Passenger rail service is provided by the public company Amtrak; regular mail delivery is provided by the U.S. Postal Service; some cities, including Los Angeles, have publicly owned electric power companies.

Price regulation limits the price that a monopolist is allowed to charge.

Regulation In the United States, the more common answer has been to leave the industry in private hands but subject it to regulation. In particular, most local utilities like electricity, land line telephone service, natural gas, and so on are covered by price regulation that limits the prices they can charge.

We saw in Chapter 4 that imposing a price ceiling on a competitive industry is a recipe for shortages, black markets, and other nasty side effects. Doesn’t imposing a limit on the price that, say, a local gas company can charge have the same effects?

Not necessarily: a price ceiling on a monopolist need not create a shortage—in the absence of a price ceiling, a monopolist would charge a price that is higher than its marginal cost of production. So even if forced to charge a lower price—as long as that price is above MC and the monopolist at least breaks even on total output—the monopolist still has an incentive to produce the quantity demanded at that price.

Oligopoly: The Legal Framework

To understand oligopoly pricing in practice, we must be familiar with the legal constraints under which oligopolistic firms operate. In the United States, oligopoly first became an issue during the second half of the nineteenth century, when the growth of railroads—themselves an oligopolistic industry—created a national market for many goods. Large firms producing oil, steel, and many other products soon emerged. The industrialists quickly realized that profits would be higher if they could limit price competition. So many industries formed cartels—that is, they signed formal agreements to limit production and raise prices. Until 1890, when the first federal legislation against such cartels was passed, this was perfectly legal.

261

However, although these cartels were legal, they weren’t legally enforceable—members of a cartel couldn’t ask the courts to force a firm that was violating its agreement to reduce its production. And firms often did violate their agreements, for the reason already suggested by our duopoly example: there is always a temptation for each firm in a cartel to produce more than it is supposed to.

In 1881 clever lawyers at John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company came up with a solution—the so-called trust. In a trust, shareholders of all the major companies in an industry placed their shares in the hands of a board of trustees who controlled the companies. This, in effect, merged the companies into a single firm that could then engage in monopoly pricing. In this way, the Standard Oil Trust established what was essentially a monopoly of the oil industry, and it was soon followed by trusts in sugar, whiskey, lead, cottonseed oil, and linseed oil.

Antitrust policy consists of efforts undertaken by the government to prevent oligopolistic industries from becoming or behaving like monopolies.

Eventually there was a public backlash, driven partly by concern about the economic effects of the trust movement, partly by fear that the owners of the trusts were simply becoming too powerful. The result was the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, which was intended both to prevent the creation of more monopolies and to break up existing ones. At first this law went largely unenforced. But over the decades that followed, the federal government became increasingly committed to making it difficult for oligopolistic industries either to become monopolies or to behave like them. Such efforts are known to this day as antitrust policy.

One of the most striking early actions of antitrust policy was the breakup of Standard Oil in 1911. (Its components formed the nuclei of many of today’s large oil companies—Standard Oil of New Jersey became Exxon, Standard Oil of New York became Mobil, and so on.) In the 1980s a long-running case led to the breakup of Bell Telephone, which once had a monopoly of both local and long-distance phone service in the United States. As we mentioned earlier, the Justice Department reviews proposed mergers between companies in the same industry and will bar mergers that it believes will reduce competition.

Among advanced countries, the United States is unique in its long tradition of antitrust policy. Until recently, other advanced countries did not have policies against price-fixing, and some had even supported the creation of cartels, believing that it would help their own firms against foreign rivals. But the situation has changed radically over the past 25 years, as the European Union (EU)—a supranational body tasked with enforcing anti-trust policy for its member countries—has converged toward U.S. practices. Today, EU and U.S. regulators often target the same firms because price-fixing has “gone global” as international trade has expanded.

During the early 1990s, the United States instituted an amnesty program in which a price-fixer receives a much-reduced penalty if it informs on its co-conspirators. In addition, Congress substantially increased maximum fines levied upon conviction. These two new policies clearly made informing on your cartel partners a dominant strategy, and it has paid off: in recent years, executives from Belgium, Britain, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Mexico, the Netherlands, South Korea, and Switzerland, as well as from the United States, have been convicted in U.S. courts of cartel crimes. As one lawyer commented, “you get a race to the courthouse” as each conspirator seeks to be the first to come clean.

Life has gotten much tougher over the past few years if you want to operate a cartel. So what’s an oligopolist to do?

262

Tacit Collusion and Price Wars

When firms limit production and raise prices in a way that raises one anothers’ profits, even though they have not made any formal agreement, they are engaged in tacit collusion.

If a real industry were as simple as our lysine example, it probably wouldn’t be necessary for the company presidents to meet or do anything that could land them in jail. Both firms would realize that it was in their mutual interest to restrict output to 30 million pounds each and that any short-term gains to either firm from producing more would be much less than the later losses as the other firm retaliated. Despite the fact that firms have no way of making an enforceable agreement to limit output and raise prices (and are in legal jeopardy if they even discuss prices), they manage to act “as if” they had such an agreement. When this happens, we say that firms engage in tacit collusion. So even without any explicit agreement, the firms would probably achieve the tacit collusion needed to maximize their combined profits.

Real industries are nowhere near that simple. Nonetheless, in most oligopolistic industries, most of the time, the sellers do appear to succeed in keeping prices above their noncooperative level. Tacit collusion, in other words, is the normal state of oligopoly.

Although tacit collusion is common, it rarely allows an industry to push prices all the way up to their monopoly level; collusion is usually far from perfect. As we discuss next, a variety of factors make it hard for an industry to coordinate on high prices.

Less Concentration In a less concentrated industry, the typical firm will have a smaller market share than in a more concentrated industry. This tilts firms toward noncooperative behavior because when a smaller firm cheats and increases its output, it gains for itself all of the profit from the higher output. And if its rivals should retaliate by increasing their output, the firm’s losses are limited because of its relatively modest market share. A less concentrated industry is often an indication that there are low barriers to entry.

Complex Products and Pricing Schemes In our lysine example the two firms produce only one product. In reality, however, oligopolists often sell thousands or even tens of thousands of different products. Under these circumstances, keeping track of what other firms are producing and what prices they are charging is difficult. This makes it hard to determine whether a firm is cheating on the tacit agreement.

Differences in Interests In the lysine example, a tacit agreement for the firms to split the market equally is a natural outcome, probably acceptable to both firms. In real industries, however, firms often differ both in their perceptions about what is fair and in their real interests.

For example, suppose that Ajinomoto was a long-established lysine producer and ADM a more recent entrant to the industry. Ajinomoto might feel that it deserved to continue producing more than ADM, but ADM might feel that it was entitled to 50% of the business. (A disagreement along these lines was one of the contentious issues in those meetings the FBI was filming.)

Alternatively, suppose that ADM’s marginal costs were lower than Ajinomoto’s. Even if they could agree on market shares, they would then disagree about the profit-maximizing level of output.

Bargaining Power of Buyers Often oligopolists sell not to individual consumers but to large buyers—other industrial enterprises, nationwide chains of stores, and so on. These large buyers are in a position to bargain for lower prices from the oligopolists: they can ask for a discount from an oligopolist and warn that they will go to a competitor if they don’t get it. An important reason large retailers like Walmart are able to offer lower prices to customers than small retailers is precisely their ability to use their size to extract lower prices from their suppliers.

263

These difficulties in enforcing tacit collusion have sometimes led companies to defy the law and create illegal cartels. We’ve already examined the cases of the lysine industry and the chocolate industry. An older, classic example was the U.S. electrical equipment conspiracy of the 1950s, which led to the indictment of and jail sentences for some executives. The industry was one in which tacit collusion was especially difficult because of all the reasons just mentioned. There were many firms—40 companies were indicted. They produced a very complex array of products, often more or less custom-built for particular clients. They differed greatly in size, from giants like General Electric to family firms with only a few dozen employees. And the customers in many cases were large buyers like electrical utilities, which would normally try to force suppliers to compete for their business. Tacit collusion just didn’t seem practical—so executives met secretly and illegally to decide who would bid what price for which contract.

A price war occurs when tacit collusion breaks down and prices collapse.

Because tacit collusion is often hard to achieve, most oligopolies charge prices that are well below what the same industry would charge if it were controlled by a monopolist—or what they would charge if they were able to collude explicitly. In addition, sometimes collusion breaks down and there is a price war. A price war sometimes involves simply a collapse of prices to their noncooperative level. Sometimes they even go below that level, as sellers try to put each other out of business or at least punish what they regard as cheating.

The Price Wars of Christmas

During the last several holiday seasons, the toy aisles of American retailers have been the scene of cutthroat competition: During the 2012 Christmas shopping season, Amazon cut prices on toys earlier than usual. In response, Target, Toys “R” Us, and Best Buy offered price-match guarantees on identical products that were advertised at online stores, including Amazon. So extreme is the price-cutting that since 2003 three toy retailers—KB Toys, FAO Schwartz, and Zany Brainy—have been forced into bankruptcy.

What is happening? The turmoil can be traced back to trouble in the toy industry itself as well as to changes in toy retailing. Every year for several years, overall toy sales have fallen a few percentage points as children increasingly turn to video games and the Internet. There have also been new entrants into the toy business: Walmart and Target have expanded their number of stores and have been aggressive price-cutters. The result is much like a story of tacit collusion sustained by repeated interaction run in reverse: because the overall industry is in a state of decline and there are new entrants, the future payoff from collusion is shrinking. The predictable outcome is a price war.

Since retailers depend on holiday sales for nearly half of their annual sales, the holidays are a time of particularly intense price-cutting. Traditionally, the biggest shopping day of the year has been “Black Friday,” the day after Thanksgiving. But in an effort to expand sales and undercut rivals, retailers—particularly Walmart—have now begun their price-cutting earlier in the fall. Now it begins in early November, well before Thanksgiving. In 2012, Amazon offered new deals every hour leading up to Black Friday, starting the Monday before Thanksgiving.

264

With other retailers feeling as if they have no choice but to follow this pattern, we have the phenomenon known as “creeping Christmas”: the price wars of Christmas arrive earlier each year.

Quick Review

- By reducing output and raising price above marginal cost, a monopolist captures some of the consumer surplus as profit and causes deadweight loss. To avoid deadweight loss, government policy attempts to curtail monopoly behavior.

- Natural monopoly poses a harder policy problem. Two solutions are public ownership and price regulation.

- Oligopolies operate under legal restrictions in the form of antitrust policy. But many succeed in achieving tacit collusion.

- Tacit collusion is limited by a number of factors, including large numbers of firms, complex products and pricing, differences in interests among firms, and bargaining power of buyers. When collusion breaks down, there is a price war.

Check Your Understanding 8-3

Question

L3GhHbkc7MCgKJd/0yOqHha0yJiE6gSlsxk9oxtKthq9F95TrBkqeMau/+n4ibJEKtNcj1ZMMCEZxrVBLWGyQWckM03unBQCZt1hlRu/nqS6xL2w8BxBita7fjH6LysPp+iloYvXvS4fonQ36DeOI+C4ctwSJTPNGcdQPFl5kNJevDxR47w7z2xm8EuMpUO8xKez9PyHGDs5UUCFTmbQ/5g2yxTy7xOaGXH+BRi+Fh1YS3hCRTjsr0tqnBImE0yGWrbPxpHiICJGn8hf+j92H9OqTsL9pCadThOR3MQ3x41IVtwCN+tuyScglP7apRsD9e6WA37Hun6tk0Ll7lGSS9BFY1CrE+Ype4XLbIPqQsT84iKo4J4uZ/7dyFhsw0W+cfmBYrAfRrpAeo3q85qTtimv4ZxcesZ7AIzFONDxGwEeSR2ugBtL7ewOQMR0T+AyqEDfxt1iRwt3+5q7mCH34Jk0ZBRMEDBNCYLjJn/cQXJopNHkcPqrbV2CVqu4wO8e28yRiTPdmfdynDFD3Hnw/8MfULQdQr+LTIv5dukxGvbnT6dgJi2H/brJa89xZ3Jh3EH1BZHWLfjHE75IWG60nUoK1NfzVGGAc87xg9NV/7jpctyIdw3IHzMSh+RJkA7QkPn769ebo9xS5vJAUA2XZdUzZ1Euz3rVBeO3Gwonz2gmK/14zuhjEWZ6vUbqsU1s7z5su2J2A5bTd8H07L1MMypUap5Ffk86qGFR9ZzLqVeZBHHGDmLvkhnkKPaJoLVJgQnKUUdSy8dVWZbEvaWDwIobItFxKukm1r7kzg==Cable Internet service is a natural monopoly. So the government should intervene only if it believes that price exceeds average total cost, where average total cost is based on the cost of laying the cable. In this case it should impose a price ceiling equal to average total cost. Otherwise, it should do nothing.Question

mWLkApvXifq+oqV65p1ZHsDCaqPi4VsLe2+UdFRbU3CymfKrZYA6EGY3Tb2Q80A/bINr49SabYRobkvnhLPCV6Ou/bIx66K1BHq62bxyMWakVjEBxa5n+cu9el5Oel8npcwSlmrGkeAF4NAUxLZWa5HMPiKMiXIHfwFpc4InnBDS7p7BxYOZfaDy6OAfxup9PjFPqSz9/+FIPeBioYd46McaCDXgRs2VOl48PETAOq4Z6cXU+un7PQ1hqXTt0L7ZN2MeTqlSPI/ip3iXnaFtmtAk9Xvjql8qlSS3NgRISH0gjmE7HpTbEf5Hnhw7vc0qdHUAZdiKsJ4kC7AC3nxTwyAvFLNWnxNjf1vesgYfQBwd0Ai8PLLZpjh4TgxnWXNWFBKK6XUVrb2g+WM8Azf9wryIp4x+BjoQMFBQI1QNWLHwmrya1Gj1PLtMJmZkeU7Dayg5dxE6joTTQniGw7ShjvZcod0YR1iDumQLrqOELsX1yyjabPSYXJTd6MHGm19L0paN5SR4Ny5j9oxqUxjdJ0j7PLzCfOEwbipCQuEmNrxvWlDGAe3u/yNX7Dhj9k++yygsQasnd01hM4welpQfNX5Q20rIAWj+RmJ1HLcR/LSiMdG6/gWs3Zsfua1BD3oCIqrSyqyT21oG+FPu6AOox1T0loQbHuQhXT3HAdFy0TyIdpkCMyEDUvmls5mifuMctBYUkMSP0FWRIgU2B8kZQmmnneiuu7Z7wQ3APisH+4g=The government should approve the merger only if it fosters competition by transferring some of the company’s landing slots to another, competing airline.

Question

GezJzX8sxLpTGB3s0XRwcBqjaao8e8IAf7WyhoO7KocbYLswjl9G7hjkwRJyb5vCSrFMYodaImnBPs3QH6C+D93IiT7aXORk7M2VD1NSVLFF4LRGoHNClWa48U6JFwoLGbNBGyzZZTbDh0LLZgvbTbxQOsgLYGGmq9Okv3hpWorEOSHYlHDQTP+V7OgN9xX4t0PLOsG+r/jVLhbzQyvi9vgmCIhWte/pZ3kc1i26HoxQQvo+False. As can be seen from Figure 8-8, panel (b), the inefficiency arises from the fact that some of the consumer surplus is transformed into deadweight loss (the yellow area), not that it is transformed into profit (the green area).

Question

KOmXga90FudyTm/t0mHWuGEJ2HlQmYvPgiGSNy/xI2SZdcizL+rNxOoeLBoaa7ZN4yl14y7z5bAUzAeoZ3ZD2vwc9bBNlaYGqcqHTnSRNBLlBrPRZJwved9TaxoGifw/K9xHSpQ5/YRrgxNHH6PyyTEP/wL0TrXkV3FovVUDvHAnqCKQ64pAXIjly7Z6ozd2V9TN/XQb7FuFeE6rrdcv9TU/ICOaCFDEuzAHFWcc6/kK3xRjQKiCv0ifRER/jSTPTila8Q7TQOk34xL+/nsKOWuUpsRMI+rgOVXVV5kJwSg=True. If a monopolist sold to all customers who have a valuation greater than or equal to marginal cost, all mutually beneficial transactions would occur and there would be no deadweight loss.

Solutions appear at back of book.