13 APPENDIX: Taxes and the Multiplier

In the chapter, we described how taxes that depend positively on real GDP reduce the size of the multiplier and act as an automatic stabilizer for the economy. Let’s look a little more closely at the mathematics of how this works.

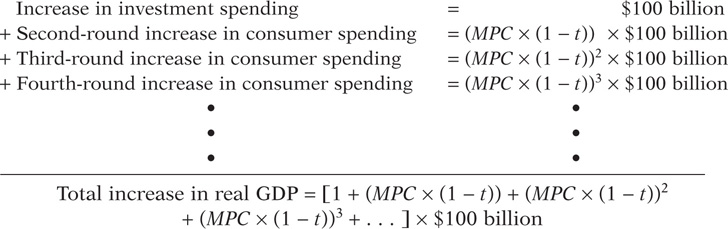

Specifically, let’s assume that the government “captures” a fraction t of any increase in real GDP in the form of taxes, where t, the tax rate, is a fraction between 0 and 1. And let’s repeat the exercise we carried out in Chapter 11, where we consider the effects of a $100 billion increase in investment spending. The same analysis holds for any autonomous increase in aggregate spending—

The $100 billion increase in investment spending initially raises real GDP by $100 billion (the first round). In the absence of taxes, disposable income would rise by $100 billion. But because part of the rise in real GDP is collected in the form of taxes, disposable income only rises by (1 − t) × $100 billion. The second-

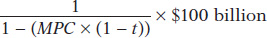

As we pointed out in Chapter 11, an infinite series of the form 1 + x + x2 + …, with 0 < x < 1, is equal to 1/(1 − x). In this example, x = (MPC × (1 − t)). So the total effect of a $100 billion increase in investment spending, taking into account all the subsequent increases in consumer spending, is to raise real GDP by:

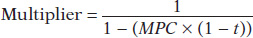

When we calculated the multiplier assuming away the effect of taxes, we found that it was 1/(1 − MPC). But when we assume that a fraction t of any change in real GDP is collected in the form of taxes, the multiplier is:

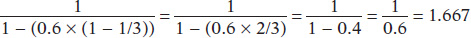

This is always a smaller number than 1/(1 − MPC), and its size diminishes as t grows. Suppose, for example, that MPC = 0.6. In the absence of taxes, this implies a multiplier of 1/(1 − 0.6) = 1/0.4 = 2.5. But now let’s assume that t = 1/3, that is, that 1/3 of any increase in real GDP is collected by the government. Then the multiplier is: