Oligopoly in Practice

In an earlier Economics in Action, we described how the four leading chocolate companies in Canada were allegedly colluding to raise prices for many years. Collusion is not, fortunately, the norm. But how do oligopolies usually work in practice? The answer depends both on the legal framework that limits what firms can do and on the underlying ability of firms in a given industry to cooperate without formal agreements.

The Legal Framework

To understand oligopoly pricing in practice, we must be familiar with the legal constraints under which oligopolistic firms operate. In the United States, oligopoly first became an issue during the second half of the nineteenth century, when the growth of railroads—

Large firms producing oil, steel, and many other products soon emerged. The industrialists quickly realized that profits would be higher if they could limit price competition. So, many industries formed cartels—

However, although these cartels were legal, they weren’t legally enforceable—

In 1881 clever lawyers at John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company came up with a solution—

Contrasting Approaches to Antitrust Regulation

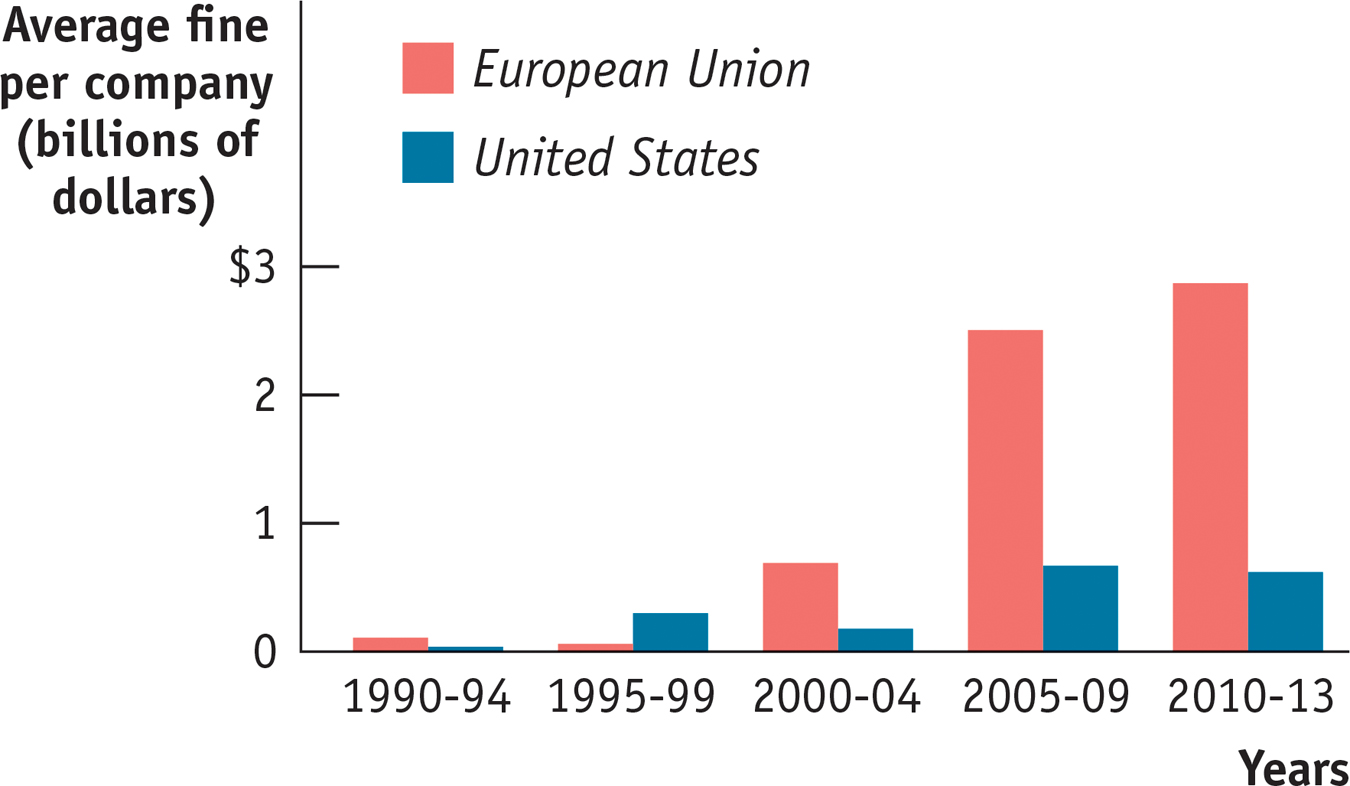

In the European Union, a competition commission enforces competition and antitrust regulation for the 28 member nations. The commission has the authority to block mergers, force companies to sell subsidiaries, and impose heavy fines if it determines that companies have acted unfairly to inhibit competition.

Although companies are able to dispute charges at a hearing once a complaint has been issued, if the commission feels that its own case is convincing, it rules against the firm and levies a penalty. Companies that believe they have been unfairly treated have only limited recourse. Critics complain that the commission acts as prosecutor, judge, and jury.

In contrast, charges of unfair competition in the United States must be made in court, where lawyers for the Federal Trade Commission have to present their evidence to independent judges. Companies employ legions of highly trained and highly paid lawyers to counter the government’s case. For U.S. regulators, there is no guarantee of success. In fact, judges in many cases have found in favor of companies and against the regulators. Moreover, companies can appeal unfavorable decisions, so reaching a final verdict can take several years.

Companies, not surprisingly, prefer the American system. The accompanying figure further shows why. In recent years, on average, fines for unfair competition have been higher in the European Union than in the United States.

Observers, however, criticize both systems for their inadequacies. In the slow-

Sources: European Commission, Department of Justice Workload Statistics; PACIFIC Exchange Rate Service at University of British Columbia.

Antitrust policy consists of efforts undertaken by the government to prevent oligopolistic industries from becoming or behaving like monopolies.

Eventually there was a public backlash, driven partly by concern about the economic effects of the trust movement, partly by fear that the owners of the trusts were simply becoming too powerful. The result was the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, which was intended both to prevent the creation of more monopolies and to break up existing ones. At first this law went largely unenforced. But over the decades that followed, the federal government became increasingly committed to making it difficult for oligopolistic industries either to become monopolies or to behave like them. Such efforts are known to this day as antitrust policy.

One of the most striking early actions of antitrust policy was the breakup of Standard Oil in 1911. (Its components formed the nuclei of many of today’s large oil companies—

Among advanced countries, the United States is unique in its long tradition of antitrust policy. Until recently, other advanced countries did not have policies against price-

During the early 1990s, the United States instituted an amnesty program in which a price-

Life has gotten much tougher over the past few years if you want to operate a cartel. So what’s an oligopolist to do?

Tacit Collusion and Price Wars

If a real industry were as simple as our lysine example, it probably wouldn’t be necessary for the company presidents to meet or do anything that could land them in jail. Both firms would realize that it was in their mutual interest to restrict output to 30 million pounds each and that any short-

Real industries are nowhere near that simple. Nonetheless, in most oligopolistic industries, most of the time, the sellers do appear to succeed in keeping prices above their noncooperative level. Tacit collusion, in other words, is the normal state of oligopoly.

Although tacit collusion is common, it rarely allows an industry to push prices all the way up to their monopoly level; collusion is usually far from perfect. As we discuss next, there are four factors that make it hard for an industry to coordinate on high prices.

Less Concentration In a less concentrated industry, the typical firm will have a smaller market share than in a more concentrated industry. This tilts firms toward noncooperative behavior because when a smaller firm cheats and increases its output, it gains for itself all of the profit from the higher output. And if its rivals retaliate by increasing their output, the firm’s losses are limited because of its relatively modest market share. A less concentrated industry is often an indication that there are low barriers to entry.

Complex Products and Pricing Schemes In our lysine example the two firms produce only one product. In reality, however, oligopolists often sell thousands or even tens of thousands of different products. Under these circumstances, keeping track of what other firms are producing and the prices they are charging is difficult. This makes it hard to determine whether a firm is cheating on the tacit agreement.

Differences in Interests In the lysine example, a tacit agreement for the firms to split the market equally is a natural outcome, probably acceptable to both firms. In real industries, however, firms often differ both in their perceptions about what is fair and in their real interests.

For example, suppose that Ajinomoto was a long-

Alternatively, suppose that ADM’s marginal costs were lower than Ajinomoto’s. Even if they could agree on market shares, they would then disagree about the profit-

Bargaining Power of Buyers Often oligopolists sell not to individual consumers but to large buyers—

These difficulties in enforcing tacit collusion have sometimes led companies to defy the law and create illegal cartels. We’ve already examined the cases of the lysine industry and the chocolate industry. An older, classic example was the U.S. electrical equipment conspiracy of the 1950s, which led to the prosecution of and jail sentences for some executives. The industry was one in which tacit collusion was especially difficult because of the reasons just mentioned.

There were many firms—

40 companies were indicted. They produced a very complex array of products, often more or less custom-

built for particular clients. They differed greatly in size, from giants like General Electric to family firms with only a few dozen employees.

The customers in many cases were large buyers like electrical utilities, which would normally try to force suppliers to compete for their business.

Tacit collusion just didn’t seem practical—

A price war occurs when tacit collusion breaks down and prices collapse.

Because tacit collusion is often hard to achieve, most oligopolies charge prices that are well below what the same industry would charge if it were controlled by a monopolist—

Product Differentiation and Price Leadership

Lysine is lysine: there was no question in anyone’s mind that ADM and Ajinomoto were producing the same good and that consumers would make their decision about which company’s lysine to buy based on the price.

In many oligopolies, however, firms produce products that consumers regard as similar but not identical. A $10 difference in the price won’t make many customers switch from a Ford to a Chrysler, or vice versa. Sometimes the differences between products are real, like differences between Froot Loops and Wheaties; sometimes, like differences between brands of vodka (which is supposed to be tasteless), they exist mainly in the minds of consumers. Either way, the effect is to reduce the intensity of competition among the firms: consumers will not all rush to buy whichever product is cheapest.

Product differentiation is an attempt by a firm to convince buyers that its product is different from the products of other firms in the industry.

As you might imagine, oligopolists welcome the extra market power that comes when consumers think that their product is different from that of competitors. So in many oligopolistic industries, firms make considerable efforts to create the perception that their product is different—

A firm that tries to differentiate its product may do so by altering what it actually produces, adding “extras,” or choosing a different design. It may also use advertising and marketing campaigns to create a differentiation in the minds of consumers, even though its product is more or less identical to the products of rivals.

A classic case of how products may be perceived as different even when they are really pretty much the same is over-

Whatever the nature of product differentiation, oligopolists producing differentiated products often reach a tacit understanding not to compete on price. For example, during the years when the great majority of cars sold in the United States were produced by the Big Three auto companies (General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler), there was an unwritten rule that none of the three companies would try to gain market share by making its cars noticeably cheaper than those of the other two.

In price leadership, one firm sets its price first, and other firms then follow.

But then who would decide on the overall price of cars? The answer was normally General Motors: as the biggest of the three, it would announce its prices for the year first, and the other companies would match it. This pattern of behavior, in which one company tacitly sets prices for the industry as a whole, is known as price leadership.

Firms that have a tacit understanding not to compete on price often engage in intense nonprice competition, using advertising and other means to try to increase their sales.

Interestingly, firms that have a tacit agreement not to compete on price often engage in vigorous nonprice competition—adding new features to their products, spending large sums on ads that proclaim the inferiority of their rivals’ offerings, and so on.

Perhaps the best way to understand the mix of cooperation and competition in such industries is with a political analogy. During the long Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, the two countries engaged in intense rivalry for global influence. They not only provided financial and military aid to their allies; they sometimes supported forces trying to overthrow governments allied with their rival (as the Soviet Union did in Vietnam in the 1960s and early 1970s, and as the United States did in Afghanistan from 1979 until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991). They even sent their own soldiers to support allied governments against rebels (as the United States did in Vietnam and the Soviet Union did in Afghanistan). But they did not get into direct military confrontations with each other; open warfare between the two superpowers was regarded by both as too dangerous—

Price wars aren’t as serious as shooting wars, but the principle is the same.

How Important Is Oligopoly?

We have seen that, across industries, oligopoly is far more common than either perfect competition or monopoly. When we try to analyze oligopoly, the economist’s usual way of thinking—

Given the prevalence of oligopoly, then, is the analysis we developed in earlier chapters, which was based on perfect competition, still useful?

The conclusion of the great majority of economists is yes. For one thing, important parts of the economy are fairly well described by perfect competition. And even though many industries are oligopolistic, in many cases the limits to collusion keep prices relatively close to marginal costs—

It is also true that predictions from supply and demand analysis are often valid for oligopolies. For example, in Chapter 5 we saw that price controls will produce shortages. Strictly speaking, this conclusion is certain only for perfectly competitive industries. But in the 1970s, when the U.S. government imposed price controls on the definitely oligopolistic oil industry, the result was indeed to produce shortages and lines at the gas pumps.

So how important is it to take account of oligopoly? Most economists adopt a pragmatic approach. As we have seen in this chapter, the analysis of oligopoly is far more difficult and messy than that of perfect competition; so in situations where they do not expect the complications associated with oligopoly to be crucial, economists prefer to adopt the working assumption of perfectly competitive markets. They always keep in mind the possibility that oligopoly might be important; they recognize that there are important issues, from antitrust policies to price wars, where trying to understand oligopolistic behavior is crucial.

We will follow the same approach in the chapters that follow.

ECONOMICS in Action: The Price Wars of Christmas

The Price Wars of Christmas

Over the last decade, the toy aisles of American retailers have been the scene of cutthroat competition. The 2011 Christmas shopping season saw Elmo at the center of a price-

What is happening? The turmoil can be traced back to trouble in the toy industry itself as well as to changes in toy retailing. Every year for several years now, overall toy sales have fallen a few percentage points as children increasingly turn to video games and the internet.

The result is much like a story of tacit collusion sustained by repeated interaction run in reverse: because the overall industry has been in a state of decline and there are new entrants, the future payoff from collusion is shrinking. The predictable outcome is a price war.

Since retailers depend on holiday sales for nearly half of their annual sales, the holidays are a time of particularly intense price-

And with each passing year, the holiday price-

With toy retailers forced to cut prices to keep pace with their rivals or lose sales, we have a phenomenon known as “creeping Christmas”: the price wars of Christmas arrive earlier each year.

Quick Review

Oligopolies operate under legal restrictions in the form of antitrust policy. But many succeed in achieving tacit collusion.

Tacit collusion is limited by a number of factors, including large numbers of firms, complex products and pricing, differences in interests among firms, and bargaining power of buyers. When collusion breaks down, there is a price war.

To limit competition, oligopolists often engage in product differentiation. When products are differentiated, it is sometimes possible for an industry to achieve tacit collusion through price leadership.

Oligopolists often avoid competing directly on price, engaging in nonprice competition through advertising and other means instead.

14-4

Question 14.6

Which of the following factors are likely to support the conclusion that there is tacit collusion in this industry? Which are not? Explain.

For many years the price in the industry has changed infrequently, and all the firms in the industry charge the same price. The largest firm publishes a catalog containing a “suggested” retail price. Changes in price coincide with changes in the catalog.

There has been considerable variation in the market shares of the firms in the industry over time.

Firms in the industry build into their products unnecessary features that make it hard for consumers to switch from one company’s products to another company’s products.

Firms meet yearly to discuss their annual sales forecasts.

Firms tend to adjust their prices upward at the same times.

Solutions appear at back of book.

!worldview!Virgin Atlantic Blows the Whistle... or Blows It?

The United Kingdom is home to two long-

The rivalry between the two has ranged from relatively peaceable to openly hostile over the years. In the 1990s, British Airways lost a court case alleging it had engaged in “dirty tricks” to drive Virgin out of business. In April 2010, however, British Airways may well have wondered if the tables had been turned.

It all began in mid-

Eventually, three Virgin executives decided to blow the whistle in exchange for immunity from prosecution. British Airways immediately suspended its executives under suspicion and paid fines of nearly $500 million to U.S. and U.K. authorities. And in 2010 four British Airways executives were prosecuted by British authorities for their alleged role in the conspiracy.

The lawyers for the executives argued that although the two airlines had swapped information, this was not proof of a criminal conspiracy. In fact, they argued, Virgin was so fearful of American regulators that it had admitted to criminal behavior before confirming that it had indeed committed an offense. One of the defense lawyers, Clare Montgomery, argued that because U.S. laws against anti-

In late 2011 the case came to a shocking end for Virgin Atlantic and U.K. authorities. Citing e-

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 14.7

Jgcvqvm4YUl+qPoy0/ztqVe/22SiohDZPBhDqiEagnazs9xBG6szsTnbc7dZ3+LBRPrC2quV03yr55unJSTjsiOON9oKaqE+jzhbER5k4eJPx9sFa02LGyaYpsHbeh3LvPOKWyDihq3e0HlST2tdx3KeZnkc+kXv4ARIzEeHEoAEMwigw9TO+u4Lz1zvKItf7Dj5F4RU34w=Explain why Virgin Atlantic and British Airlines might collude in response to increased oil prices. Was the market conducive to collusion or not?Question 14.8

/nLQBLDKOsl8E3YUg/NCk+E8BfpO35L5uyrj61GsJEHvl2PQ5pZKHsNgVT0qX+LFfWIfN9GRrXjWs79HW6c8+1ab3sNjwgquasbUO8QOK6vylwF8+6dVmg+RykrsAPbIqGJ8QAI1NECrPPTSVdcwSlvSJ1UMbBBUXjWRQ9BgspQlhPJwHow would you determine whether illegal behavior actually occurred? What might explain these events other than illegal behavior?Question 14.9

9/kEzeRD2OVcMJRCJepIunWTzQ2EWhOw1D6HnNVPFbscTtvcaBSLYUN5k1zaIYFtz5csLWQGKA77YRWsL9CANn9jnG2bduxjJAgjsYiNdh+JbXDdpf7Jqw==Explain the dilemma facing the two airlines as well as their individual executives.