20: Uncertainty, Risk, and Private Information

!arrow! What You Will Learn in This Chapter

That risk is a key feature of the economy and that most people are risk-

averse Why diminishing marginal utility makes people risk-

averse and determines the premium they are willing to pay to reduce risk How risk can be traded—

the risk- averse can pay others to assume part of their risk How exposure to risk can be reduced through diversification and pooling

The special problems posed by private information—

when some people know things that other people do not

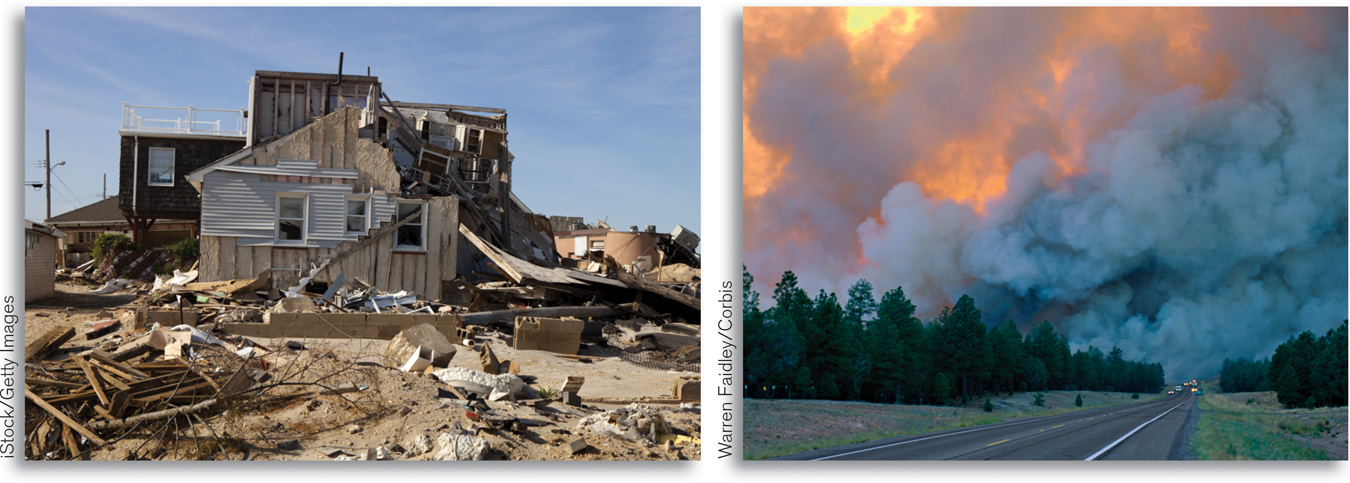

EXTREME WEATHER

Warren Faidley/Corbis

WHEN HURRICANE SANDY blasted onshore in New York and New Jersey in October 2012, residents and local governments were stunned but well prepared. They had, after all, been through Hurricane Irene just 14 months earlier. Irene resulted in 56 deaths and almost $16 billion in costs. But Sandy, a bigger category 2 storm, was even more devastating. It killed 160 people, destroyed homes and businesses, left over 8 million households without power for weeks, and led to shortages of essentials like clean water and gasoline. It even flooded the New York City subway system for the first time in 110 years. In total, Sandy inflicted $65 billion in damages on the U.S. economy.

But Hurricane Sandy was only one part of a pattern of extreme weather in the United States in 2011 and 2012. In August of 2012, Hurricane Isaac hit Louisiana, resulting in 7 deaths and more than $2 billion in damage. If that were not enough, record-

Moreover, these estimates of damages significantly understated the true cost of these weather events because many of the uninsured or underinsured (those with insurance insufficient to cover their losses) failed to report their losses.

Anyone who lives in an area subject to extreme weather knows that uncertainty is a feature of the real world. Up to this point, we have assumed that people make decisions with knowledge of exactly how the future will unfold. (The exception being health insurance decisions.) In reality, people often make economic decisions, such as whether to build a house in a coastal area, without full knowledge of future events. As the victims of these extreme weather events learned, making decisions when the future is uncertain carries with it the risk of loss.

It is often possible for individuals to use markets to reduce their risk. For example, hurricane victims who had insurance were able to receive some, if not complete, compensation for their losses. In fact, through insurance and other devices, the modern economy offers many ways for individuals to reduce their exposure to risk.

However, a market economy cannot always solve the problems created by uncertainty. Markets do very well at coping with risk when two conditions hold: when risk can be reasonably well diversified and when the probability of loss is equally well known by everyone.

Over the past several years, the increase in extreme weather events has led many insurers to no longer rely on diversification for weather-

But in practice, the second condition is often the more limiting one. Markets run into trouble when some people know things that others do not—

In this chapter we’ll examine why most people dislike risk. Then we’ll explore how a market economy allows people to reduce risk at a price. Finally, we’ll turn to the special problems created for markets by private information.