Consumer Surplus, Producer Surplus, and the Gains from Trade

One of the 12 core principles of economics we introduced in Chapter 1 is that markets are a remarkably effective way to organize economic activity: they generally make society as well off as possible given the available resources. The concepts of consumer surplus and producer surplus can help us deepen our understanding of why this is so.

The Gains from Trade

Let’s return to the market in used textbooks but now consider a much bigger market—

Similarly, we can line up outgoing students, who are potential sellers of the book, in order of their cost—

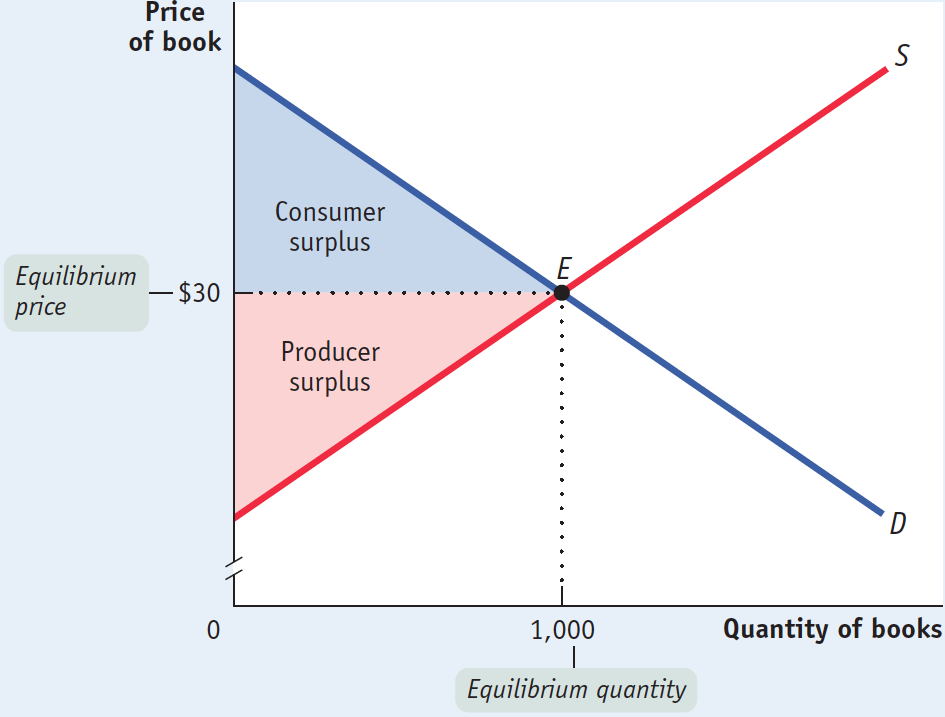

The total surplus generated in a market is the total net gain to consumers and producers from trading in the market. It is the sum of the producer and the consumer surplus.

As we have drawn the curves, the market reaches equilibrium at a price of $30 per book, and 1,000 books are bought and sold at that price. The two shaded triangles show the consumer surplus (blue) and the producer surplus (red) generated by this market. The sum of consumer and producer surplus is known as the total surplus generated in a market.

The striking thing about this picture is that both consumers and producers gain—

But are we as well off as we could be? This brings us to the question of the efficiency of markets.

The Efficiency of Markets

Markets produce gains from trade, but in Chapter 1 we made an even bigger claim: that markets are usually efficient. That is, we claimed that once the market has produced its gains from trade, there is no way to make some people better off without making other people worse off, except under some well-

The analysis of consumer and producer surplus helps us understand why markets are usually efficient. To gain more intuition into why this is so, consider the fact that market equilibrium is just one way of deciding who consumes the good and who sells the good. There are other possible ways of making that decision.

Consider, for example, the case of kidney transplants, discussed earlier in For Inquiring Minds, in which a decision must be made about who receives one. It is not possible to use a market to decide because in this situation, human organs are involved. Instead, in the past, kidneys were allocated according to a recipient’s wait time—

To further our understanding of why markets usually work so well, imagine a committee charged with improving on the market equilibrium by deciding who gets and who gives up a used textbook. The committee’s ultimate goal is to bypass the market outcome and devise another arrangement, one that would produce higher total surplus.

Let’s consider the three ways in which the committee might try to increase the total surplus:

Reallocate consumption among consumers

Reallocate sales among sellers

Change the quantity traded

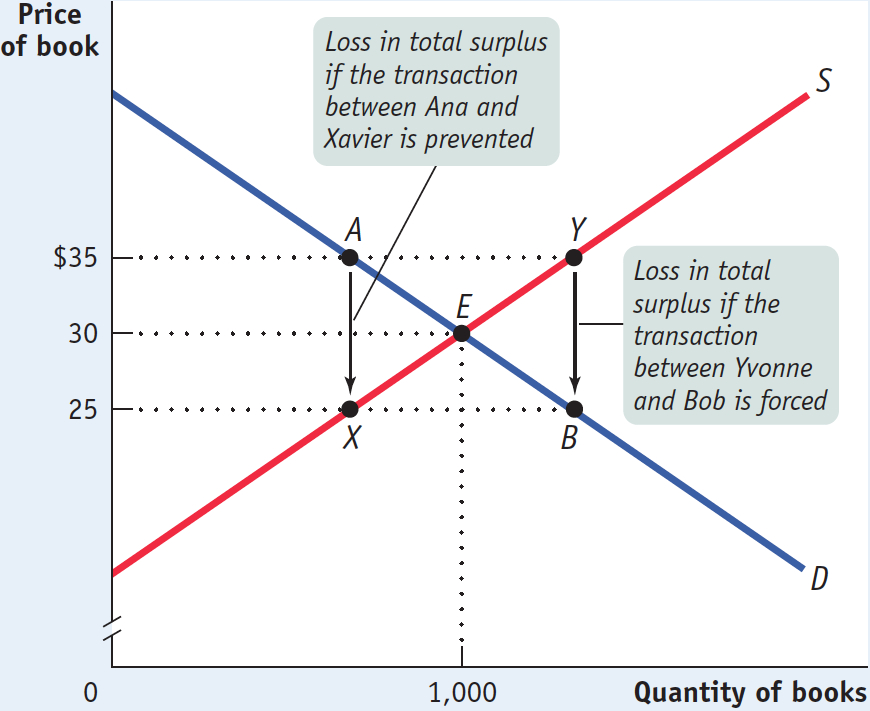

Reallocate Consumption Among Consumers The committee might try to increase total surplus by selling books to different consumers. Figure 4-12 shows why this will result in lower surplus compared to the market equilibrium outcome. Here we have smooth demand and supply curves because there are many buyers and sellers. Points A and B show the positions on the demand curve of two potential buyers of used books, Ana and Bob. As we can see from the figure, Ana is willing to pay $35 for a book, but Bob is willing to pay only $25. Since the market equilibrium price is $30, under the market outcome Ana buys a book and Bob does not.

Now suppose the committee reallocates consumption. This would mean taking the book away from Ana and giving it to Bob. Since the book is worth $35 to Ana but only $25 to Bob, this change reduces total consumer surplus by $35 − $25 = $10. Moreover, this result doesn’t depend on which two students we pick. Every student who buys a book at the market equilibrium has a willingness to pay of $30 or more, and every student who doesn’t buy a book has a willingness to pay of less than $30.

So reallocating the good among consumers always means taking a book away from a student who values it more and giving it to one who values it less. This necessarily reduces total consumer surplus.

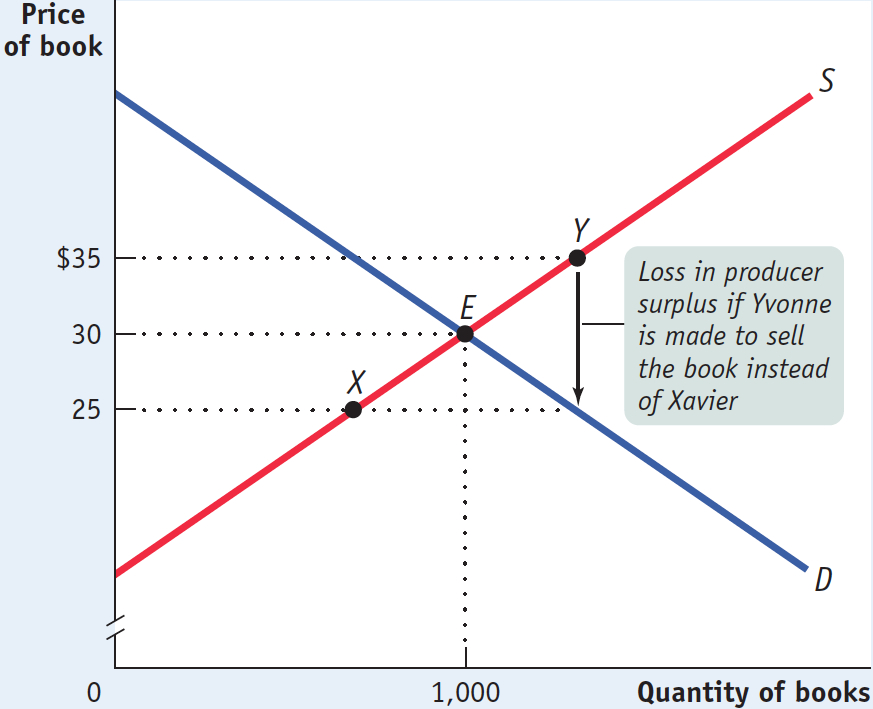

Reallocate Sales Among Sellers The committee might try to increase total surplus by altering who sells their books, taking sales away from sellers who would have sold their books at the market equilibrium and instead compelling those who would not have sold their books at the market equilibrium to sell them.

Figure 4-13 shows why this will result in lower surplus. Here points X and Y show the positions on the supply curve of Xavier, who has a cost of $25, and Yvonne, who has a cost of $35. At the equilibrium market price of $30, Xavier would sell his book but Yvonne would not sell hers. If the committee reallocated sales, forcing Xavier to keep his book and Yvonne to sell hers, total producer surplus would be reduced by $35 − $25 = $10.

Again, it doesn’t matter which two students we choose. Any student who sells a book at the market equilibrium has a lower cost than any student who keeps a book. So reallocating sales among sellers necessarily increases total cost and reduces total producer surplus.

Change the Quantity Traded The committee might try to increase total surplus by compelling students to trade either more books or fewer books than the market equilibrium quantity.

Figure 4-14 shows why this will result in lower surplus. It shows all four students: potential buyers Ana and Bob, and potential sellers Xavier and Yvonne. To reduce sales, the committee will have to prevent a transaction that would have occurred in the market equilibrium—

Once again, this result doesn’t depend on which two students we pick: any student who would have sold the book at the market equilibrium has a cost of $30 or less, and any student who would have purchased the book at the market equilibrium has a willingness to pay of $30 or more. So preventing any sale that would have occurred in the market equilibrium necessarily reduces total surplus.

Finally, the committee might try to increase sales by forcing Yvonne, who would not have sold her book at the market equilibrium, to sell it to someone like Bob, who would not have bought a book at the market equilibrium. Because Yvonne’s cost is $35, but Bob is only willing to pay $25, this transaction reduces total surplus by $10. And once again it doesn’t matter which two students we pick—

The key point to remember is that once this market is in equilibrium, there is no way to increase the gains from trade. Any other outcome reduces total surplus. (This is why the United Network for Organ Sharing, or UNOS, is trying, with its new guidelines based on “net survival benefit,” to reproduce the allocation of donated kidneys that would occur if there were a competitive market for the organs.) We can summarize our results by stating that an efficient market performs four important functions:

It allocates consumption of the good to the potential buyers who most value it, as indicated by the fact that they have the highest willingness to pay.

It allocates sales to the potential sellers who most value the right to sell the good, as indicated by the fact that they have the lowest cost.

It ensures that every consumer who makes a purchase values the good more than every seller who makes a sale, so that all transactions are mutually beneficial.

It ensures that every potential buyer who doesn’t make a purchase values the good less than every potential seller who doesn’t make a sale, so that no mutually beneficial transactions are missed.

As a result of these four functions, any way of allocating the good other than the market equilibrium outcome lowers total surplus.

There are three caveats, however. First, although a market may be efficient, it isn’t necessarily fair. In fact, fairness, or equity, is often in conflict with efficiency. We’ll discuss this next.

The second caveat is that markets sometimes fail. As we mentioned in Chapter 1, under some well-

Third, even when the market equilibrium maximizes total surplus, this does not mean that it results in the best outcome for every individual consumer and producer. Other things equal, each buyer would like to pay a lower price and each seller would like to receive a higher price. So if the government were to intervene in the market—

Equity and Efficiency

For many patients who need kidney transplants, the new UNOS guidelines, covered earlier, were unwelcome news. Unsurprisingly, those who have been waiting years for a transplant have found the guidelines, which give precedence to younger patients, … well … unfair. And the guidelines raise other questions about fairness: Why limit potential transplant recipients to Americans? Why include younger patients with other chronic diseases? Why not give precedence to those who have made recognized contributions to society? And so on.

The point is that efficiency is about how to achieve goals, not what those goals should be. For example, UNOS decided that its goal is to maximize the life span of kidney recipients. Some might have argued for a different goal, and efficiency does not address which goal is the best. What efficiency does address is the best way to achieve a goal once it has been determined—in this case, using the UNOS concept of “net survival benefit.”

It’s easy to get carried away with the idea that markets are always right and that economic policies that interfere with efficiency are bad. But that would be misguided because there is another factor to consider: society cares about equity, or what’s “fair.”

As we discussed in Chapter 1, there is often a trade-

ECONOMICS in Action: Take The Keys, Please

Take The Keys, Please

“Airbnb was really born from a math problem,” said its co-

From that bout of desperation-

What’s motivating all this sharing? Well, it isn’t an outbreak of altruism—

Quick Review

Total surplus measures the gains from trade in a market.

Markets are efficient except under some well-

defined conditions. We can demonstrate the efficiency of a market by considering what happens to total surplus if we start from the equilibrium and reallocate consumption, reallocate sales, or change the quantity traded. Any outcome other than the market equilibrium reduces total surplus, which means that the market equilibrium is efficient. Because society cares about equity, government intervention in a market that reduces efficiency while increasing equity can be justified.

4-3

Question 4.3

Using the tables in Check Your Understanding 4-1 and 4-2, find the equilibrium price and quantity in the market for cheese-

stuffed jalapeno peppers. What is total surplus in the equilibrium in this market, and who receives it? Question 4.4

Show how each of the following three actions reduces total surplus:

Having Josey consume one fewer pepper, and Casey one more pepper, than in the market equilibrium

Having Cara produce one fewer pepper, and Jamie one more pepper, than in the market equilibrium

Having Josey consume one fewer pepper, and Cara produce one fewer pepper, than in the market equilibrium

Question 4.5

Suppose UNOS decides to further alter its guidelines for the allocation of donated kidneys, no longer relying solely on the concept of “net survival benefit” but also giving preference to patients with small children. If “total surplus” in this case is defined to be the total life span of kidney recipients, is this new guideline likely to reduce, increase, or leave total surplus unchanged? How might you justify this new guideline?

Solutions appear at back of book.