Understanding the Tax System

An excise tax is the easiest tax to analyze, making it a good vehicle for understanding the general principles of tax analysis. However, in the United States today, excise taxes are actually a relatively minor source of government revenue. In this section, we develop a framework for understanding more general forms of taxation and look at some of the major taxes used in the United States.

Tax Bases and Tax Structure

The tax base is the measure or value, such as income or property value, that determines how much tax an individual or firm pays.

Every tax consists of two pieces: a base and a structure. The tax base is the measure or value that determines how much tax an individual or firm pays. It is usually a monetary measure, like income or property value. The tax structure specifies how the tax depends on the tax base. It is usually expressed in percentage terms; for example, homeowners in some areas might pay yearly property taxes equal to 2% of the value of their homes.

The tax structure specifies how the tax depends on the tax base.

Some important taxes and their tax bases are as follows:

An income tax is a tax on an individual’s or family’s income.

Income tax: a tax that depends on the income of an individual or family from wages and investments

A payroll tax is a tax on the earnings an employer pays to an employee.

Payroll tax: a tax that depends on the earnings an employer pays to an employee

A sales tax is a tax on the value of goods sold.

Sales tax: a tax that depends on the value of goods sold (also known as an excise tax)

A profits tax is a tax on a firm’s profits.

Profits tax: a tax that depends on a firm’s profits

A property tax is a tax on the value of property, such as the value of a home.

Property tax: a tax that depends on the value of property, such as the value of a home

A wealth tax is a tax on an individual’s wealth.

Wealth tax: a tax that depends on an individual’s wealth

A proportional tax is the same percentage of the tax base regardless of the taxpayer’s income or wealth.

Once the tax base has been defined, the next question is how the tax depends on the base. The simplest tax structure is a proportional tax, also sometimes called a flat tax, which is the same percentage of the base regardless of the taxpayer’s income or wealth. For example, a property tax that is set at 2% of the value of the property, whether the property is worth $10,000 or $10,000,000, is a proportional tax. Many taxes, however, are not proportional. Instead, different people pay different percentages, usually because the tax law tries to take account of either the benefits principle or the ability-

A progressive tax takes a larger share of the income of high-

Because taxes are ultimately paid out of income, economists classify taxes according to how they vary with the income of individuals. A tax that rises more than in proportion to income, so that high-

A regressive tax takes a smaller share of the income of high-

The U.S. tax system contains a mixture of progressive and regressive taxes, though it is somewhat progressive overall.

Equity, Efficiency, and Progressive Taxation

Most, though not all, people view a progressive tax system as fairer than a regressive system. The reason is the ability-

To see why, consider a hypothetical example, illustrated in Table 7-3. We assume that there are two kinds of people in the nation of Taxmania: half of the population earns $40,000 a year and half earns $80,000, so the average income is $60,000 a year. We also assume that the Taxmanian government needs to collect one-

|

Pre- |

After- |

After- |

|---|---|---|

|

$40,000 |

$30,000 |

$40,000 |

|

$80,000 |

$60,000 |

$50,000 |

TABLE 7-

One way to raise this revenue would be through a proportional tax that takes one-

Even this system might have some negative effects on incentives. Suppose, for example, that finishing college improves a Taxmanian’s chance of getting a higher-

But a strongly progressive tax system could create a much bigger incentive problem. Suppose that the Taxmanian government decided to exempt the poorer half of the population from all taxes but still wanted to raise the same amount of revenue. To do this, it would have to collect $30,000 from each individual earning $80,000 a year. As the third column of Table 7-3 shows, people earning $80,000 would then be left with income after taxes of $50,000—

The marginal tax rate is the percentage of an increase in income that is taxed away.

The point here is that any income tax system will tax away part of the gain an individual gets by moving up the income scale, reducing the incentive to earn more. But a progressive tax takes away a larger share of the gain than a proportional tax, creating a more adverse effect on incentives. In comparing the incentive effects of tax systems, economists often focus on the marginal tax rate: the percentage of an increase in income that is taxed away. In this example, the marginal tax rate on income above $40,000 is 25% with proportional taxation but 75% with progressive taxation.

Our hypothetical example is much more extreme than the reality of progressive taxation in the modern United States—

Taxes in the United States

Table 7-4 shows the revenue raised by major taxes in the United States in 2013. Some of the taxes are collected by the federal government and the others by state and local governments.

|

Federal taxes ($ billion) |

State and local taxes ($ billion) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Income |

$1,312.1 |

Income |

$334.3 |

|

Payroll |

1,106.0 |

Sales |

498.1 |

|

Profits |

338.9 |

Profits |

91.7 |

|

Property |

444.6 |

||

|

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis. |

|||

TABLE 7-

There is a major tax corresponding to five of the six tax bases we identified earlier. There are income taxes, payroll taxes, sales taxes, profits taxes, and property taxes, all of which play an important role in the overall tax system. The only item missing is a wealth tax. In fact, the United States does have a wealth tax, the estate tax, which depends on the value of someone’s estate after he or she dies. But at the time of writing, the current law phases out the estate tax over a few years, and in any case it raises much less money than the taxes shown in the table.

In addition to the taxes shown, state and local governments collect substantial revenue from other sources as varied as driver’s license fees and sewer charges. These fees and charges are an important part of the tax burden but very difficult to summarize or analyze.

Are the taxes in Table 7-4 progressive or regressive? It depends on the tax. The personal income tax is strongly progressive. The payroll tax, which, except for the Medicare portion, is paid only on earnings up to $117,000 is somewhat regressive. Sales taxes are generally regressive, because higher-

Overall, the taxes collected by the federal government are quite progressive. The second column of Table 7-5 shows estimates of the average federal tax rate paid by families at different levels of income earned in 2013. These estimates don’t count just the money families pay directly. They also attempt to estimate the incidence of taxes directly paid by businesses, like the tax on corporate profits, which ultimately falls on individual shareholders. The table shows that the federal tax system is indeed progressive, with low-

|

Income group |

Federal |

State and local |

Total |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bottom quintile |

6.4% |

12.4% |

18.8% |

||

|

Second quintile |

10.9 |

11.6 |

22.5 |

||

|

Third quintile |

15.4 |

11.2 |

26.6 |

||

|

Fourth quintile |

18.8 |

11.0 |

29.8 |

||

|

Next 10% |

20.4 |

11.0 |

31.4 |

||

|

Next 5% |

21.4 |

10.6 |

32.0 |

||

|

Next 4% |

22.0 |

10.2 |

32.2 |

||

|

Top 1% |

24.3 |

8.7 |

33.0 |

||

|

Average |

19.7 |

10.5 |

30.1 |

||

|

Source: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. |

|||||

TABLE 7-

Since 2000, the federal government has cut income taxes for most families. The largest cuts, both as a share of income and as a share of federal taxes collected, have gone to families with high incomes. As a result, the federal system is less progressive (at the time of writing) than it was in 2000 because the share of income paid by high-

As the third column of Table 7-5 shows, however, taxes at the state and local levels are generally regressive. That’s because the sales tax, the largest source of revenue for most states, is somewhat regressive, and other items, such as vehicle licensing fees, are strongly regressive.

In sum, the U.S. tax system is somewhat progressive, with the richest fifth of the population paying a somewhat higher share of income in taxes than families in the middle and the poorest fifth paying considerably less.

Yet there are important differences within the American tax system: the federal income tax is more progressive than the payroll tax, which can be seen from Table 7-5. And federal taxation is more progressive than state and local taxation.

You Think You Pay High Taxes?

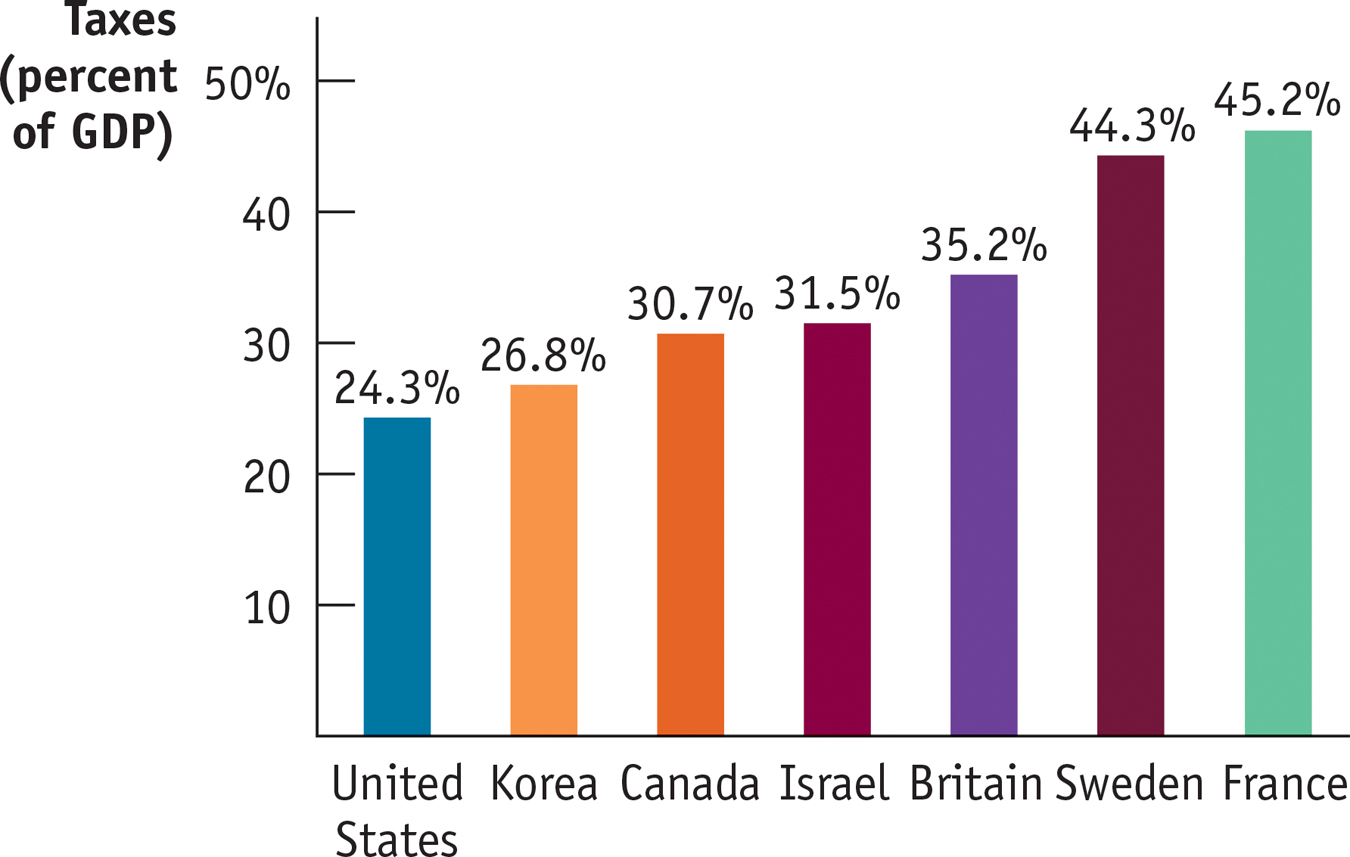

Everyone, everywhere complains about taxes. But citizens of the United States actually have less to complain about than citizens of most other wealthy countries.

To assess the overall level of taxes, economists usually calculate taxes as a share of gross domestic product—

Source: OECD.

Different Taxes, Different Principles

Why are some taxes progressive but others regressive? Can’t the government make up its mind?

There are two main reasons for the mixture of regressive and progressive taxes in the U.S. system: the difference between levels of government and the fact that different taxes are based on different principles.

State and especially local governments generally do not make much effort to apply the ability-

Although the federal government is in a better position than state or local governments to apply principles of fairness, it applies different principles to different taxes. We saw an example of this in the preceding Economics in Action. The most important tax, the federal income tax, is strongly progressive, reflecting the ability-

!worldview! FOR INQUIRING MINDS: Taxing Income versus Taxing Consumption

The U.S. government taxes people mainly on the money they make, not on the money they spend on consumption. Yet most tax experts argue that this policy badly distorts incentives. Someone who earns income and then invests that income for the future gets taxed twice: once on the original sum and again on any earnings made from the investment.

So a system that taxes income rather than consumption discourages people from saving and investing, instead providing an incentive to spend their income today. And encouraging savings and investing is an important policy goal for two reasons. First, empirical evidence shows that Americans tend to save too little for retirement and health care expenses in their later years. Second, savings and investment both contribute to economic growth.

Moving from a system that taxes income to one that taxes consumption would solve this problem. In fact, the governments of many countries get much of their revenue from a value-

The United States does not have a value-

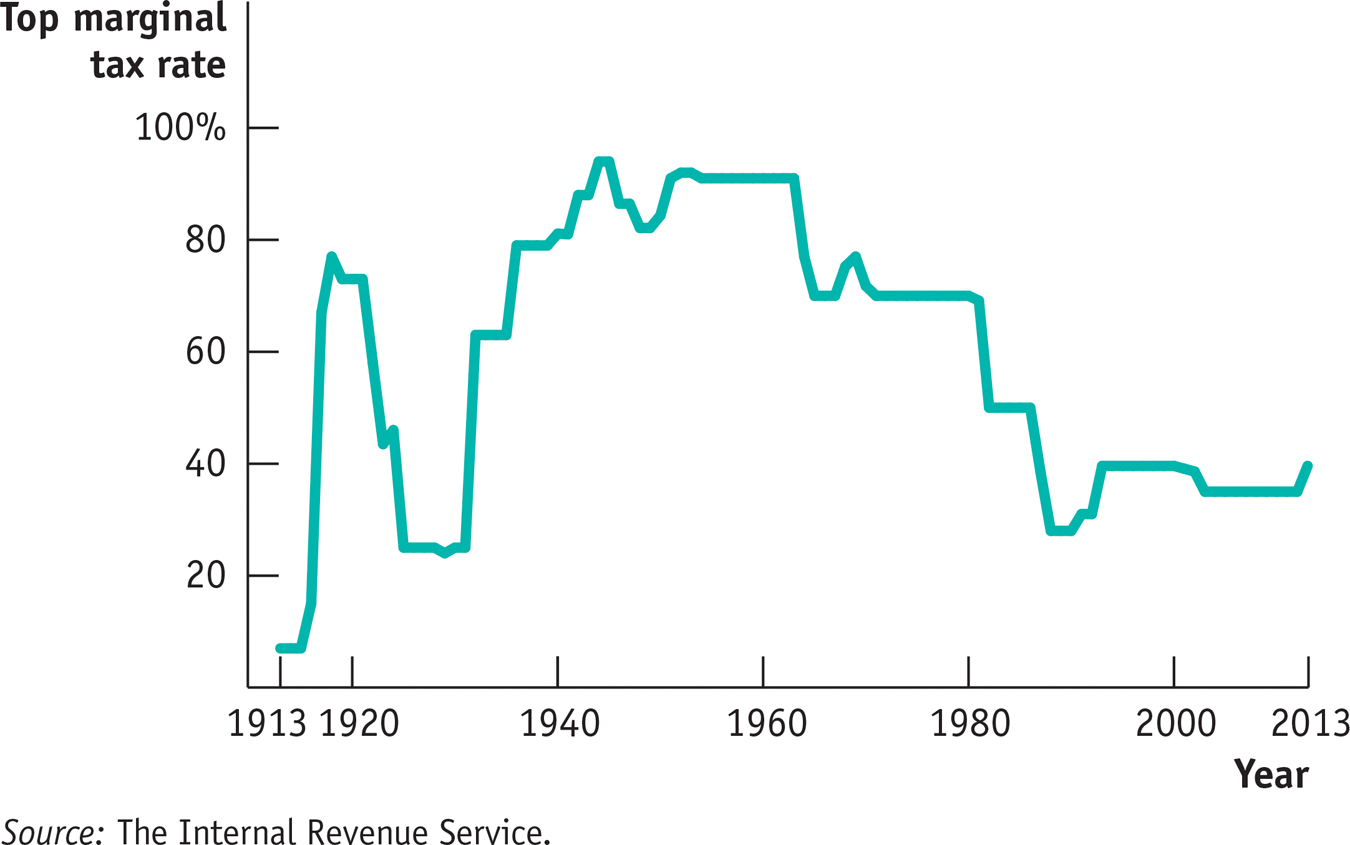

ECONOMICS in Action: The Top Marginal Income Tax Rate

The Top Marginal Income Tax Rate

The amount of money an American owes in federal income taxes is found by applying marginal tax rates on successively higher “brackets” of income. For example, in 2013 a single person paid 10% on the first $8,925 of taxable income (that is, income after subtracting exemptions and deductions); 15% on the next $27,325; and so on up to a top rate of 39.6% on his or her income, if any, over $400,000. Relatively few people (less than 1% of taxpayers) have incomes high enough to pay the top marginal rate. In fact, more than 75% of Americans pay no income tax or they fall into either the 10% or 15% bracket. But the top marginal income tax rate is often viewed as a useful indicator of the progressiv-

Figure 7-11 shows the top marginal income tax rate from 1913, when the U.S. government first imposed an income tax, to 2013. The first big increase in the top marginal rate came during World War I (1914) and was reversed after the war ended (1918). After that, the figure is dominated by two big changes: a huge increase in the top marginal rate during the administration of Franklin Roosevelt (1933–

Quick Review

Every tax consists of a tax base and a tax structure.

Among the types of taxes are income taxes, payroll taxes, sales taxes, profits taxes, property taxes, and wealth taxes.

Tax systems are classified as being proportional, progressive, or regressive.

Progressive taxes are often justified by the ability-

to- pay principle. But strongly progressive taxes lead to high marginal tax rates, which create major incentive problems. The United States has a mixture of progressive and regressive taxes. However, the overall structure of taxes is progressive.

7-4

Question 7.9

An income tax taxes 1% of the first $10,000 of income and 2% on all income above $10,000.

What is the marginal tax rate for someone with income of $5,000? How much total tax does this person pay? How much is this as a percentage of his or her income?

What is the marginal tax rate for someone with income of $20,000? How much total tax does this person pay? How much is this as a percentage of his or her income?

Is this income tax proportional, progressive, or regressive?

Question 7.10

When comparing households at different income levels, economists find that consumption spending grows more slowly than income. Assume that when income grows by 50%, from $10,000 to $15,000, consumption grows by 25%, from $8,000 to $10,000. Compare the percent of income paid in taxes by a family with $15,000 in income to that paid by a family with $10,000 in income under a 1% tax on consumption purchases. Is this a proportional, progressive, or regressive tax?

Question 7.11

True or false? Explain your answers.

Payroll taxes do not affect a person’s incentive to take a job because they are paid by employers.

A lump-

sum tax is a proportional tax because it is the same amount for each person.

Solutions appear at back of book.

Amazon versus BarnesandNoble.com

In 2014, comparison shoppers in about half of the United States found that the final price of a book on Amazon was cheaper than on its competitor, BarnesandNoble.com. Why? It’s simply a matter of taxes—

According to the law, online retailers without a physical presence in a given state can sell products without collecting sales tax. (Customers are supposed to report the transaction and pay the sales tax, which they—

In contrast, the bricks-

|

Amazon |

BarnesandNoble.com |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Price of book |

$20.69 |

$20.69 |

|

California sales tax (7.5%) |

0 |

$1.45 |

|

Shipping fee |

$3.99 |

$3.99 |

|

Final price |

$20.69 |

$22.14 |

TABLE 7-

As reported in the Wall Street Journal, interviews and company documents show that Amazon believes that its avoidance of sales tax collection has been crucial to its success in becoming the dominant retailer of books in the United States. Estimates are that Amazon would have lost as much as $653 million in sales in 2011, or 1.4% of its annual revenue, if it had been forced to collect sales tax.

Since 2012, however, after vigorous pressure from state authorities, Amazon’s ability to avoid collecting sales tax has been greatly curtailed. As of 2014 the number of states it collects sales taxes in has risen from 5 to 19. It’s part of a new strategy by Amazon, to build warehouses in the states in which it collects sales taxes, reasoning that faster delivery will keep customers loyal despite having to pay sales tax. Yet, it’s not hard to understand the view from BarnesandNoble.com that being forced to collect sales tax when Amazon is not deeply hurt its business.

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 7.12

nSCFkj27rCd6u3Va6FFtvSQx3HwoKQK5hoPvxpnNgnfvZZ4gv/3e/fdJRQRWGoSwiEuqMEO9O99aDxKrpicI/JPNNtFX4PSZpFiqymDuqhC1TNidKm8P/EEdVLpgbK/A0eRYjyqEim6WttJEP7zFcGCVpcSNESWcivPIU/gUpaig0IoGz44wgEQZmfP5PzVEo4lFajdv0Pdl/GMuZih+XuSRByow0jT7rlj3s90kvzzQz0w4bOwwiChOqX9WmlDL5NZGjyHZL16KZPWDWhat effect do you think the difference in state sales tax collection has on Amazon’s sales versus BarnesandNoble.com’s sales?Question 7.13

v7Wvg5ARqoDQYw3z2sZUjP+kX9YTtwDeOgJU3EQoFEzNBqBr90e8KVeLBFFFfY9epuDT5wZoIHZYX2BiM1/25f6rpyTJXMk9Rg1SVV2LqRN0du42WaSVtubQ7SaiphQIgTlpWFKbefEKPIPm5n8C/0v/1SB7hNy9/8q2JhgN7vUgWZ127aMY4NC5zCz74aVjViaU5Xz0hrgQQeplK2FgJe4oIHr6XwgdLy7DcdV4uFjldNDbSwMgGAUnfcsHqjdQ1D4Bm3oFaLfYLO0VtxEl08sbPI5dnuRl5xrBNjMtzpBLYFPODmPXB7C1fVHB9oUJ9scP1zAipsAx6HkRgdRxfuv9OCnCsT7l8yd0NOpyP8lVkPUbgOYUtGf/uMU511glMd0aJ0pTtaTJSrGTynFDor1WaqowegfhN8gtwChycHC8VZHDZ0+zbYHA9g+MaA/Yc9D4kERdNFt088UDSuppose sales tax is collected on all online book sales. From the evidence in this case, what do you think is the incidence of the tax between seller and buyer? What does this imply about the elasticity of supply of books by book retailers? (Hint: Compare the pre-tax prices of the book.) Question 7.14

Y4Q3ppirrGgUNJ7ueDMHKPi77e2aI2UOobg32ayeBi478oI9xQgLn8cd5UKXpYEEx/dn7ns6K9u8TubFljFD+ugNBtMIQtsymWufxwFzG7b5zm61v9p+UPoKUUT4y2RDsO35TWVZJt1oSuo3CjAnwgFyZLQ=How did Amazon’s tax strategy distort its business behavior? What measures would eliminate these distortions?