Aftershocks in Europe

One important factor bedeviling hopes for recovery was the emergence of special difficulties in several European nations—

The 2008 crisis was caused by problems with private debt, mainly home loans, which then triggered a crisis of confidence in banks. In 2011 and 2012, there were fears of a second crisis, this one arising from concerns about whether Southern European countries as well as Ireland could repay their burgeoning public debts.

Europe’s troubles first surfaced in Greece, a country with a long history of fiscal irresponsibility. In late 2009 it was revealed that the previous Greek government had understated the size of the budget deficits and the amount of government debt. This prompted lenders to refuse further loans to Greece. To prevent a default on Greek public debt, other European countries provided emergency loans to the Greek government in return for harsh cuts to the Greek government budget. But these cuts depressed the Greek economy, and by late 2011 there was general agreement that Greece would be unable to pay back its public debt in full.

By itself, this was a manageable shock for the European economy since Greece accounts for less than 3% of European GDP. Unfortunately, foot-

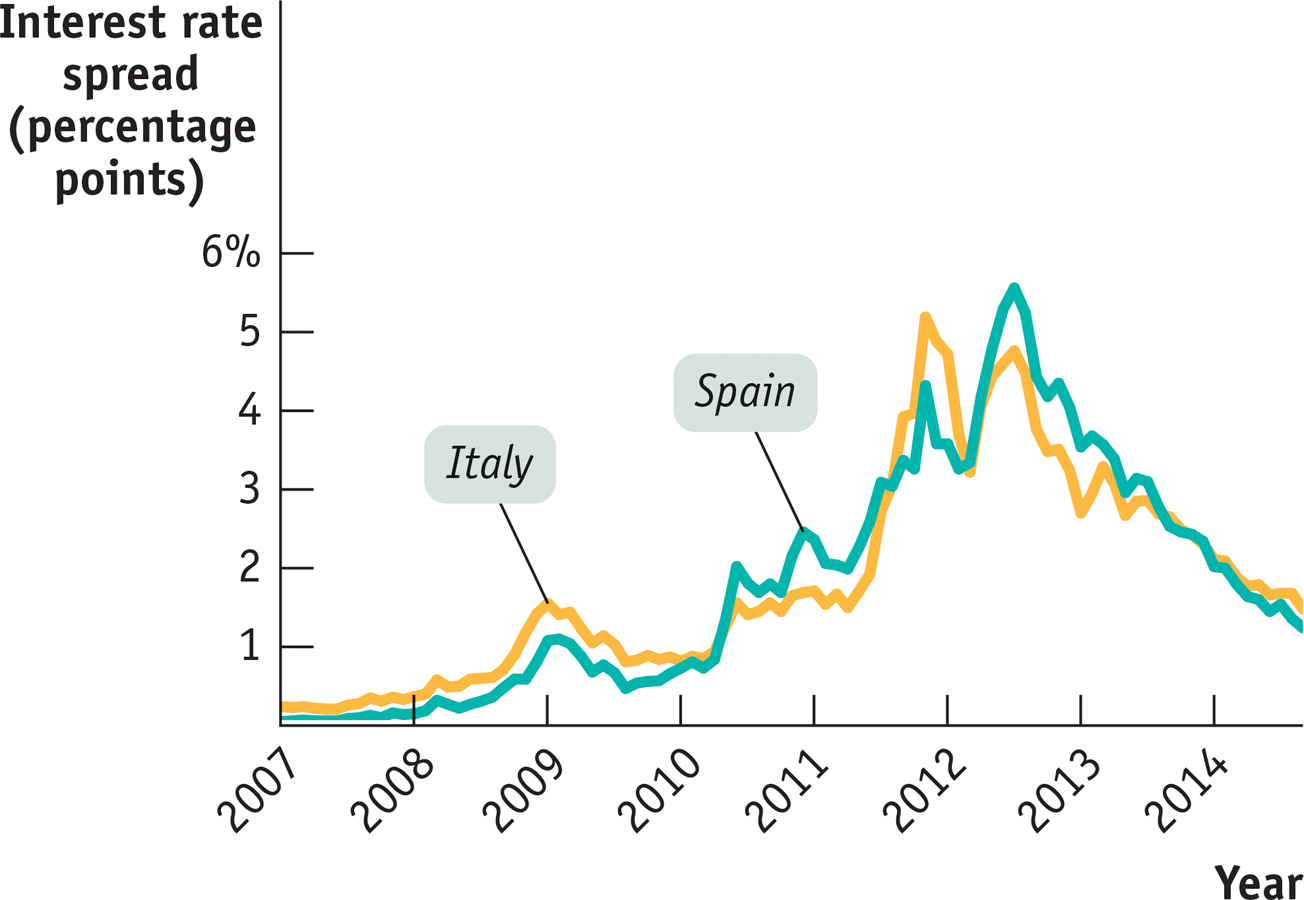

Figure 17-8 shows a measure of pressure on Italy and Spain during the 2008 and 2011 crises: the difference between interest rates on 10-

Spain’s fiscal problems were mainly fallout from the 2008 crisis. Before that crisis, Spain seemed to be in very good fiscal condition, with low debt and a budget surplus. However, Spain, like Ireland, had a huge housing bubble between 2000 and 2007. When the bubble burst, the Spanish economy fell into a deep slump, depressing tax receipts and causing large budget deficits. At the same time, there were worries that the Spanish government might eventually have to spend large amounts bailing out banks. As a result, investors began worrying about the solvency of the Spanish government and a possible default.

Italy’s case was somewhat different. Italy has long had high levels of public debt as a percentage of GDP, but it has not run large deficits in recent years; as late as the spring of 2010 its fiscal position looked fairly stable. At that point, however, investors began to have doubts about the Italian government’s solvency, in part because in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis the Italian economy was growing very slowly—

Some economists argued that the problems of Spain and Italy were exacerbated by the fact that, having adopted the euro, their debts were in effect in a foreign currency. Why does this matter? Governments like those of the United States, Britain, or Japan, which borrow in their own currencies, can’t run out of money—

This argument gained a lot of credibility in 2012, when the European Central Bank declared that it would become a lender of last resort for the eurozone by buying directly the bonds of troubled governments in that area if necessary, greatly reducing the fears of a liquidity crisis for these governments. As you can see in Figure 17-8, spreads on Spanish and Italian debt fell sharply after the announcement. Although immediate fears of government defaults in the eurozone had been greatly eased, at the time of writing Europe’s economic difficulties remain grave.