Modern Banking Crises Around the World

Around the world, banking crises are relatively frequent events. However, the ways in which they occur differ according to the banking sector’s particular institutional framework. According to a 2008 analysis by the International Monetary Fund, no fewer than 127 banking crises occurred around the world between 1970 and 2007. Most of these were in small, poor countries that lack the regulatory safeguards found in advanced countries. In poorer countries, banks generally get in trouble in much the same way: insufficient capital, poor accounting, too many loans and, often, corruption. But banks in advanced countries can also make the same mistakes—

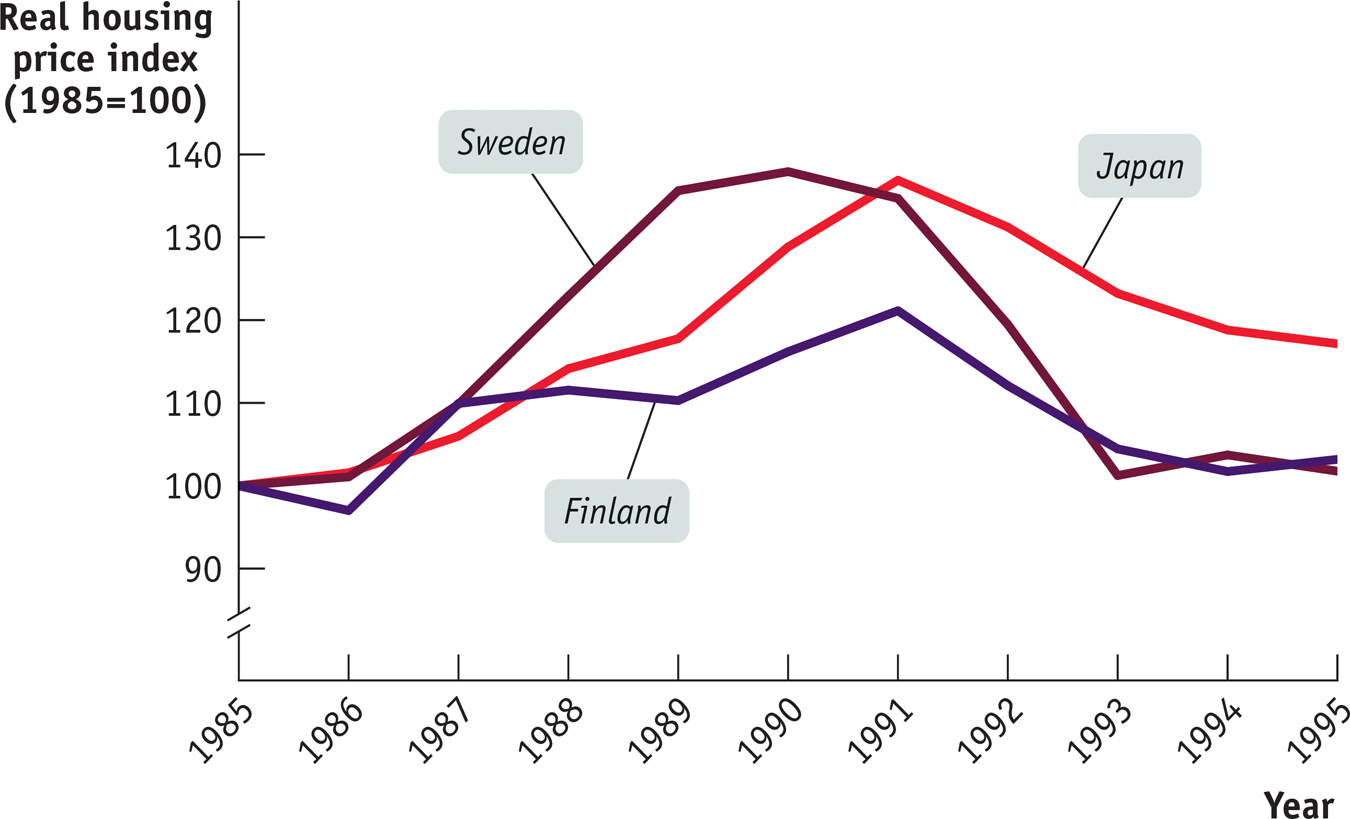

In more advanced countries, banking crises almost always occur as a consequence of an asset bubble—

In the United States, the fall of Lehman in September 2008 precipitated a banking crisis in the shadow banking sector that included financial contagion as well as financial panic, but left the depository banking sector largely unaffected. As we discussed in the opening story, the financial crisis of 2008 was devastating because of securitization, which had distributed subprime mortgage loans throughout the entire shadow banking sector both in the United States and abroad.

At the time of writing, shadow banking in the United States was still significantly smaller than it was before the crisis. Since 2008, investors have rediscovered the benefits of regulation, and the depository banking sector has grown at the expense of the shadow banking sector. However, shadow banking has certainly not gone away. China’s shadow banking sector has grown at breakneck speed in the last few years, making it the third largest in the world as of 2014 and an area of great concern to Chinese leaders. In the next section, we will learn how troubles in the banking sector soon translate into troubles for the broader economy.

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: Erin Go Broke

Erin Go Broke

For much of the 1990s and 2000s, Ireland was celebrated as an economic success story: the “Celtic Tiger” was growing at a pace the rest of Europe could only envy. But the miracle came to an abrupt halt in 2008, as Ireland found itself facing a huge banking crisis.

Like the earlier banking crises in Finland, Sweden, and Japan, Ireland’s crisis grew out of excessive optimism about real estate. Irish housing prices began rising in the 1990s, in part a result of the economy’s strong growth. However, real estate developers began betting on ever-

In 2007 the Irish real estate boom collapsed. Home prices started falling, and home sales collapsed. Many of the loans that Irish banks had made during the boom went into default. Now, so-

This created a new problem because it put Irish taxpayers on the hook for potentially huge bank losses. Until the crisis struck, Ireland appeared to be in good fiscal shape, with relatively low government debt and a budget surplus. The fallout from the banking crisis, however, led to serious questions about the solvency of the Irish government—

As in most banking crises, Ireland experienced a severe recession. The Irish unemployment rate rose from less than 5% before the crisis to more than 15% in early 2012. It was still more than 11% at the time of writing.

It’s also worth noting that Ireland’s problems were part of a broader crisis affecting several European countries, notably Spain, Portugal, and Greece. We’ll discuss this broader crisis later in the chapter.

Quick Review

Although individual bank failures are common, a banking crisis is a rare event that typically will severely harm the broader economy.

A banking crisis can occur because depository or shadow banks invest in an asset bubble or through financial contagion, set off by bank runs or by a vicious cycle of deleveraging. Largely unregulated, shadow banking is particularly vulnerable to contagion.

In 2008, an asset bubble combined with a huge shadow banking sector and a vicious cycle of deleveraging created a financial panic and banking crisis, as savers cut their spending and investors hoarded their funds, sending the economy into a steep decline.

Between the Civil War and the Great Depression, the United States suffered numerous banking crises and financial panics, each followed by a severe economic downturn. The banking reforms of the 1930s prevented another banking crisis until 2008.

Banking crises usually occur in small, poor countries, although there have been banking crises in advanced countries as well. The fall of Lehman caused a banking crisis and a financial panic in the shadow banking sector, leading investors to shift back into the depository banking sector.

17-2

Question 17.2

Regarding the Economics in Action “Erin Go Broke,” identify the following:

The asset bubble

The channel of financial contagion

Question 17.3

Again regarding “Erin Go Broke,” why do you think the Irish government tried to stabilize the situation by guaranteeing the debts of the banks? Why was this a questionable policy?

Solutions appear at back of book.