The Short-Run Aggregate Supply Curve

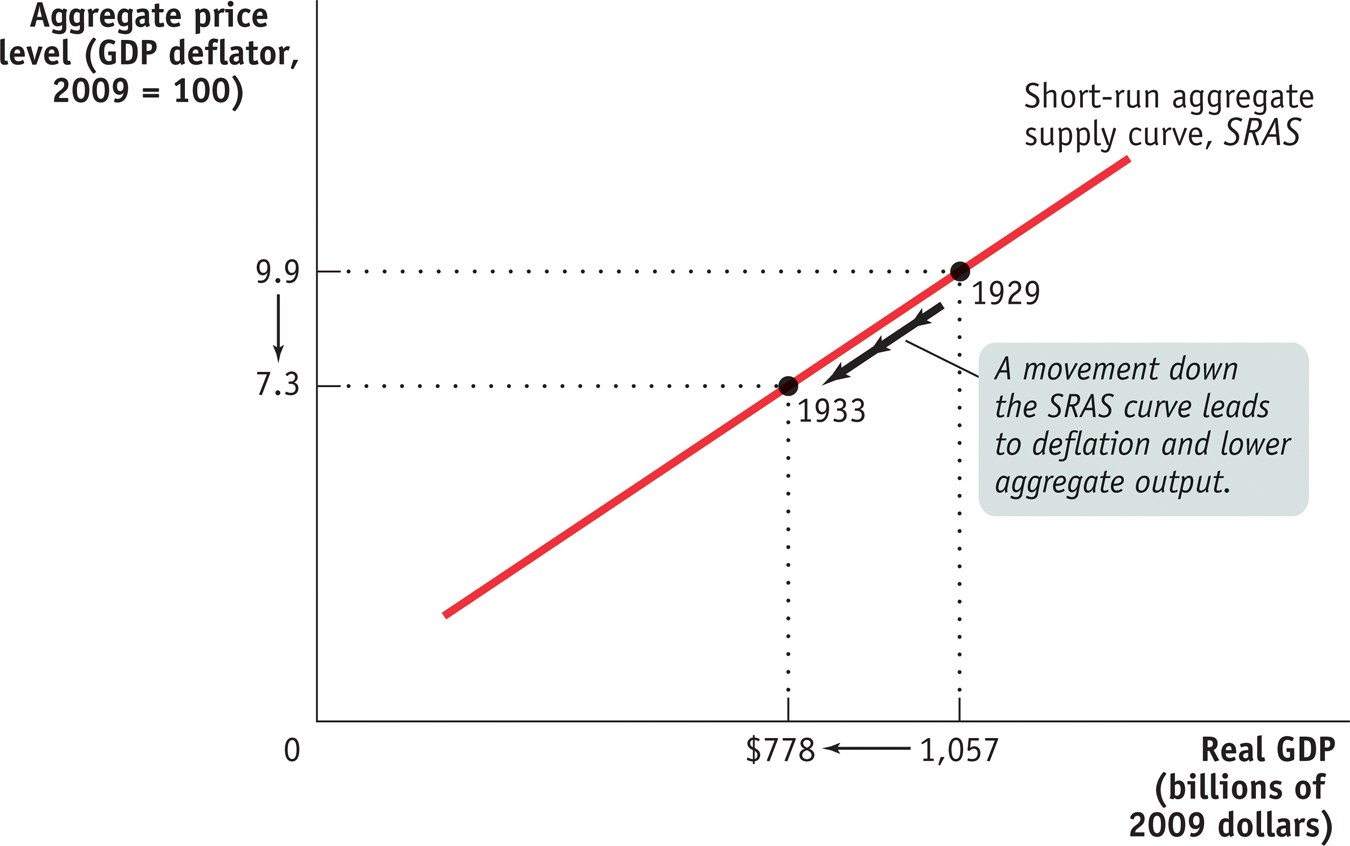

The period from 1929 to 1933 demonstrated that there is a positive relationship in the short run between the aggregate price level and the quantity of aggregate output supplied. That is, a rise in the aggregate price level is associated with a rise in the quantity of aggregate output supplied, other things equal; a fall in the aggregate price level is associated with a fall in the quantity of aggregate output supplied, other things equal. To understand why this positive relationship exists, consider the most basic question facing a producer: is producing a unit of output profitable or not? Let’s define profit per unit:

Thus, the answer to the question depends on whether the price the producer receives for a unit of output is greater or less than the cost of producing that unit of output. At any given point in time, many of the costs producers face are fixed per unit of output and can’t be changed for an extended period of time. Typically, the largest source of inflexible production cost is the wages paid to workers. Wages here refers to all forms of worker compensation, such as employer-

The nominal wage is the dollar amount of the wage paid.

Wages are typically an inflexible production cost because the dollar amount of any given wage paid, called the nominal wage, is often determined by contracts that were signed some time ago. And even when there are no formal contracts, there are often informal agreements between management and workers, making companies reluctant to change wages in response to economic conditions. For example, companies usually will not reduce wages during poor economic times—

Sticky wages are nominal wages that are slow to fall even in the face of high unemployment and slow to rise even in the face of labor shortages.

As a result of both formal and informal agreements, then, the economy is characterized by sticky wages: nominal wages that are slow to fall even in the face of high unemployment and slow to rise even in the face of labor shortages. It’s important to note, however, that nominal wages cannot be sticky forever: ultimately, formal contracts and informal agreements will be renegotiated to take into account changed economic circumstances. As the Pitfalls at the end of this section explains, how long it takes for nominal wages to become flexible is an integral component of what distinguishes the short run from the long run.

To understand how the fact that many costs are fixed in nominal terms gives rise to an upward-

Let’s start with the behavior of producers in perfectly competitive markets; remember, they take the price as given. Imagine that, for some reason, the aggregate price level falls, which means that the price received by the typical producer of a final good or service falls. Because many production costs are fixed in the short run, production cost per unit of output doesn’t fall by the same proportion as the fall in the price of output. So the profit per unit of output declines, leading perfectly competitive producers to reduce the quantity supplied in the short run.

On the other hand, suppose that for some reason the aggregate price level rises. As a result, the typical producer receives a higher price for its final good or service. Again, many production costs are fixed in the short run, so production cost per unit of output doesn’t rise by the same proportion as the rise in the price of a unit. And since the typical perfectly competitive producer takes the price as given, profit per unit of output rises and output increases.

Now consider an imperfectly competitive producer that is able to set its own price. If there is a rise in the demand for this producer’s product, it will be able to sell more at any given price. Given stronger demand for its products, it will probably choose to increase its prices as well as its output, as a way of increasing profit per unit of output. In fact, industry analysts often talk about variations in an industry’s “pricing power”: when demand is strong, firms with pricing power are able to raise prices—

Conversely, if there is a fall in demand, firms will normally try to limit the fall in their sales by cutting prices.

The short-

Both the responses of firms in perfectly competitive industries and those of firms in imperfectly competitive industries lead to an upward-

Figure 12-5 shows a hypothetical short-

FOR INQUIRING MINDS: What’s Truly Flexible, What’s Truly Sticky

Most macroeconomists agree that the basic picture shown in Figure 12-5 is correct: there is, other things equal, a positive short-

So far we’ve stressed a difference in the behavior of the aggregate price level and the behavior of nominal wages. That is, we’ve said that the aggregate price level is flexible but nominal wages are sticky in the short run. Although this assumption is a good way to explain why the short-

On one side, some nominal wages are in fact flexible even in the short run because some workers are not covered by a contract or informal agreement with their employers. Since some nominal wages are sticky but others are flexible, we observe that the average nominal wage—the nominal wage averaged over all workers in the economy—

On the other side, some prices of final goods and services are sticky rather than flexible. For example, some firms, particularly the makers of luxury or name-

These complications, as we’ve said, don’t change the basic picture. When the aggregate price level falls, some producers cut output because the nominal wages they pay are sticky. And some producers don’t cut their prices in the face of a falling aggregate price level, preferring instead to reduce their output. In both cases, the positive relationship between the aggregate price level and aggregate output is maintained. So, in the end, the short-