Deficits, Surpluses, and Debt

When a family spends more than it earns over the course of a year, it has to raise the extra funds either by selling assets or by borrowing. And if a family borrows year after year, it will eventually end up with a lot of debt.

The same is true for governments. With a few exceptions, governments don’t raise large sums by selling assets such as national parkland. Instead, when a government spends more than the tax revenue it receives—

A fiscal year runs from October 1 to September 30 and is labeled according to the calendar year in which it ends.

To interpret the numbers that follow, you need to know a slightly peculiar feature of federal government accounting. For historical reasons, the U.S. government does not keep books by calendar years. Instead, budget totals are kept by fiscal years, which run from October 1 to September 30 and are labeled by the calendar year in which they end. For example, fiscal 2014 began on October 1, 2013, and ended on September 30, 2014.

PITFALLS: DEFICITS VERSUS DEBT

DEFICITS VERSUS DEBT

One common mistake—

A deficit is the difference between the amount of money a government spends and the amount it receives in taxes over a given period—

A debt is the sum of money a government owes at a particular point in time. Debt numbers usually come with a specific date, as in “U.S. public debt at the end of fiscal 2011 was $10.1 trillion.”

Deficits and debt are linked, because government debt grows when governments run deficits. But they aren’t the same thing, and they can even tell different stories. For example, Italy, which found itself in debt trouble in 2011, had a fairly small deficit by historical standards, but it had very high debt, a legacy of past policies.

Public debt is government debt held by individuals and institutions outside the government.

At the end of fiscal 2013, the U.S. federal government had total debt equal to $17.1 trillion. However, part of that debt represented special accounting rules specifying that the federal government as a whole owes funds to certain government programs, especially Social Security. We’ll explain those rules shortly. For now, however, let’s focus on public debt: government debt held by individuals and institutions outside the government. At the end of fiscal 2013, the federal government’s public debt was “only” $12.0 trillion, or 72% of GDP. Federal public debt at the end of 2013 was larger than at the end of 2012 because the government ran a deficit in 2013: a government that runs persistent budget deficits will experience a rising level of public debt. Why is this a problem?

The American Way of Debt

How does the public debt of the United States stack up internationally? In dollar terms, we’re number one—

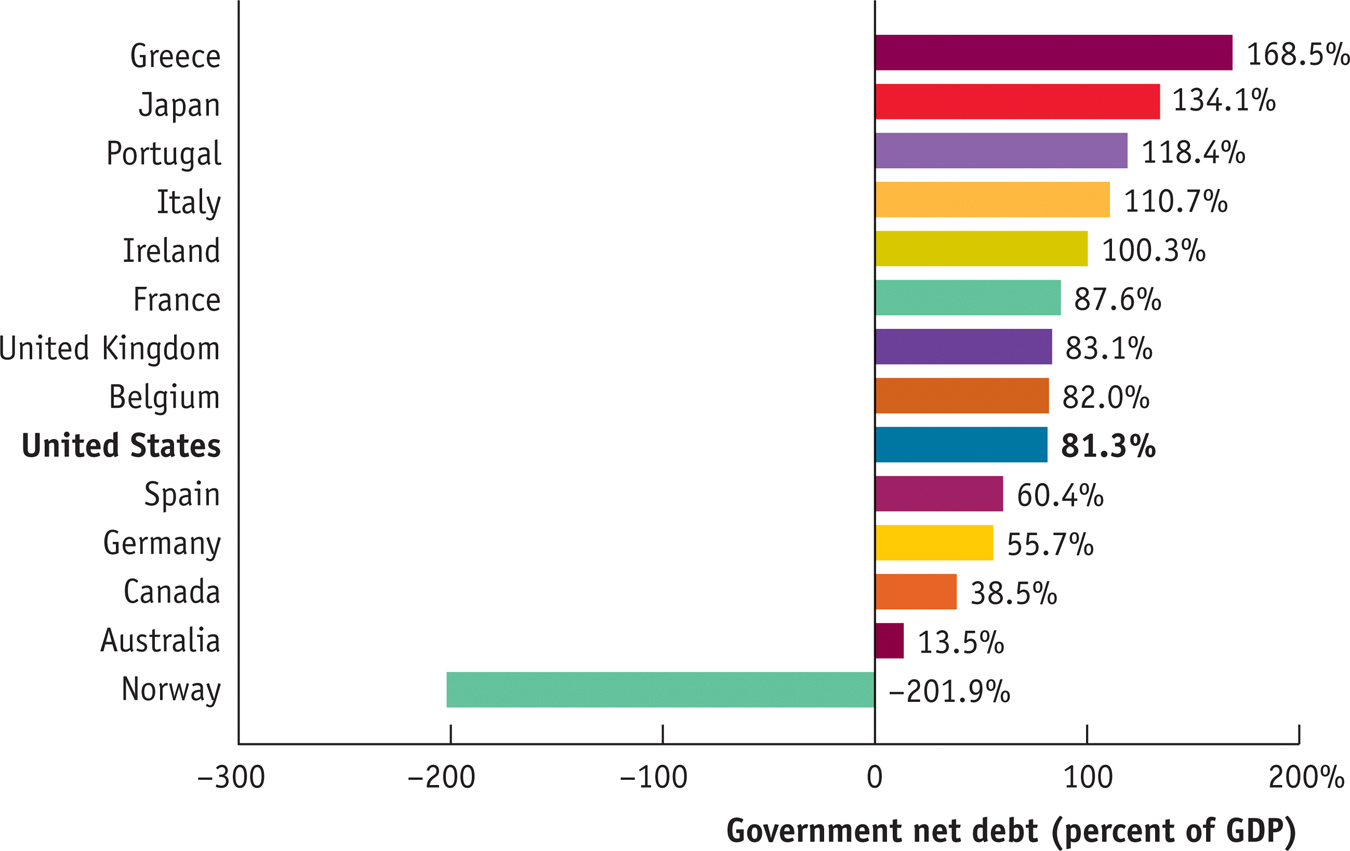

The figure shows the net public debt of a number of rich countries as a percentage of GDP at the end of 2013. Net public debt is government debt minus any assets governments may have—

It may not surprise you that Greece heads the list, and most of the other high net debt countries are European nations that have been making headlines for their debt problems. Interestingly, however, Japan is also high on the list because it used massive public spending to prop up its economy in the 1990s. Investors, however, still consider Japan a reliable government, so its borrowing costs remain low despite high net debt.

In contrast to the other countries, Norway has a large negative net public debt. What’s going on in Norway? In a word, oil. Norway is the world’s third-

Source: International Monetary Fund.