The Taylor Rule Method of Setting Monetary Policy

A Taylor rule for monetary policy is a rule that sets the federal funds rate according to the level of the inflation rate and either the output gap or the unemployment rate.

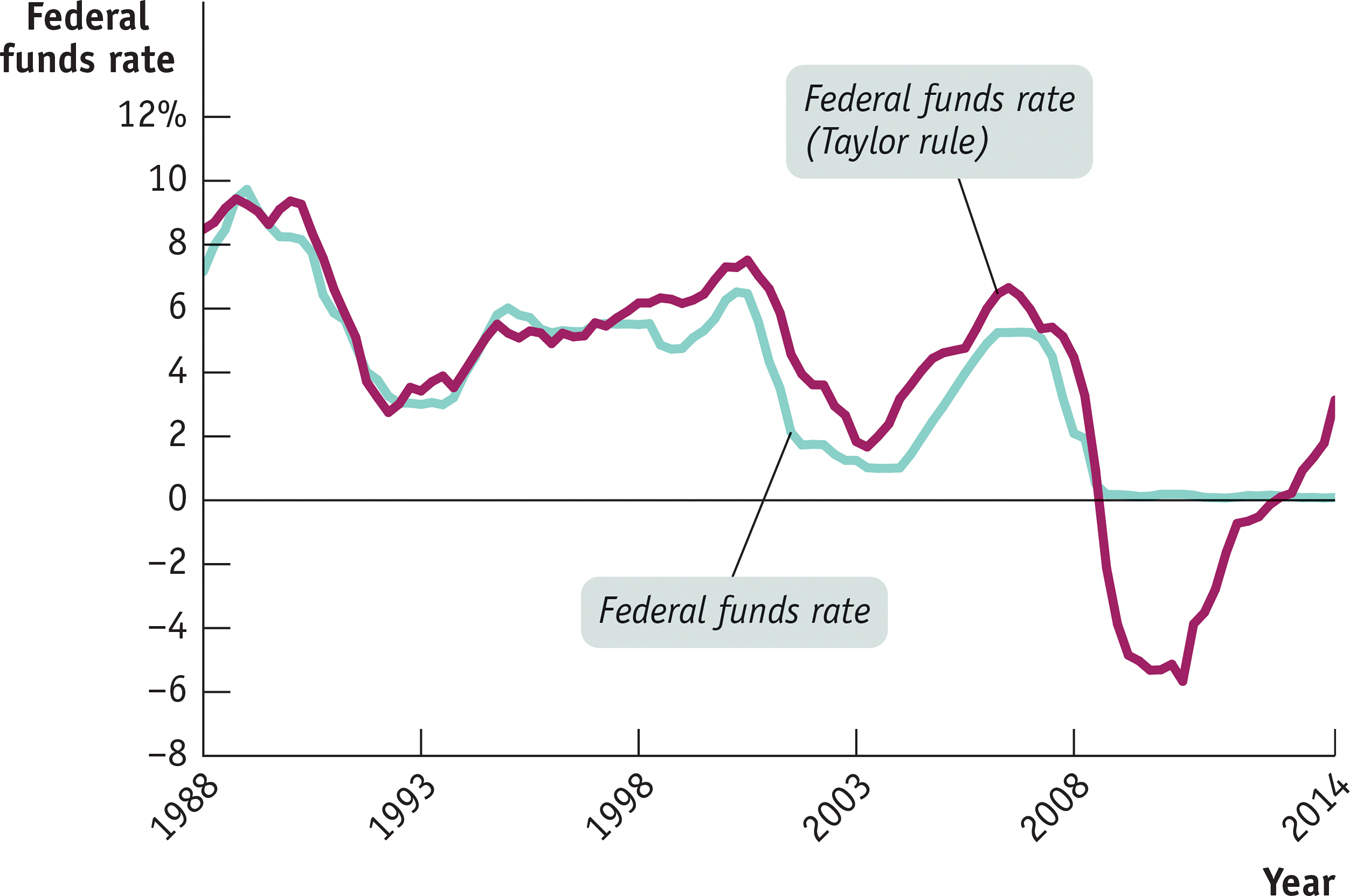

In 1993 Stanford economist John Taylor suggested that monetary policy should follow a simple rule that takes into account concerns about both the business cycle and inflation. He also suggested that actual monetary policy often looks as if the Federal Reserve was, in fact, more or less following the proposed rule. A Taylor rule for monetary policy is a rule for setting interest rates that takes into account the inflation rate and the output gap or, in some cases, the unemployment rate.

A widely cited example of a Taylor rule is a relationship among Fed policy, inflation, and unemployment estimated by economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. These economists found that between 1988 and 2008 the Fed’s behavior was well summarized by the following Taylor rule:

Federal funds rate = 2.07 + 1.28 × inflation rate − 1.95 × unemployment gap

where the inflation rate was measured by the change over the previous year in consumer prices excluding food and energy, and the unemployment gap was the difference between the actual unemployment rate and Congressional Budget Office estimates of the natural rate of unemployment.

Figure 15-9 compares the federal funds rate predicted by this rule with the actual federal funds rate from 1985 to mid-

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics; Congressional Budget Office; Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; Glenn D. Rudebusch, “The Fed’s Monetary Policy Response to the Current Crisis,” FRBSF Economic Letter #2009-